Abstract

Existing research suggests that temperamental traits that emerge early in childhood may have utility for early detection and intervention for common mental disorders. The present study examined the unique relationships between the temperament characteristics of reactivity, approach-sociability, and persistence in early childhood and subsequent symptom trajectories of psychopathology (depression, anxiety, conduct disorder, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; ADHD) from childhood to early adolescence. Data were from the first five waves of the older cohort from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (n = 4983; 51.2% male), which spanned ages 4–5 to 12–13. Multivariate ordinal and logistic regressions examined whether parent-reported child temperament characteristics at age 4–5 predicted the study child’s subsequent symptom trajectories for each domain of psychopathology (derived using latent class growth analyses), after controlling for other presenting symptoms. Temperament characteristics differentially predicted the symptom trajectories for depression, anxiety, conduct disorder, and ADHD: Higher levels of reactivity uniquely predicted higher symptom trajectories for all 4 domains; higher levels of approach-sociability predicted higher trajectories of conduct disorder and ADHD, but lower trajectories of anxiety; and higher levels of persistence were related to lower trajectories of conduct disorder and ADHD. These findings suggest that temperament is an early identifiable risk factor for the development of psychopathology, and that identification and timely interventions for children with highly reactive temperaments in particular could prevent later mental health problems.

Keywords: Temperament, developmental psychopathology, childhood, adolescence

Most common forms of psychopathology emerge in childhood or early adolescence (e.g., Kessler et al., 2005), and there is robust evidence for both homotypic and heterotypic continuity in mental disorders across the lifespan (Cole, Peeke, Martin, Truglio, & Seroczynski, 1998; Lahey, Zald, Hakes, Krueger, & Rathouz, 2014). That is, mental disorders diagnosed early in life are likely to persist over large parts of the lifespan and/or confer risk for the subsequent emergence of other mental disorders. The period from childhood to early adolescence is thus a valuable window in which to identify risk factors that may underpin the development and persistence of common mental disorders.

Temperamental traits are early emerging dispositions in the domains of affect, sociability, and attention (Putnam, Sanson & Rothbart, 2002; Thomas & Chess, 1977), and represent strong candidates as reliable indicators of psychopathology in early childhood (e.g., Beauchaine & McNulty, 2013). While research on childhood temperament characterises temperamental traits in a variety of ways (Rettew & McKee, 2005), models of temperament consistently highlight three broad dimensions of affectivity, surgency, and impulsivity/attention (Rettew & McKee, 2005; Rothbart, 2007). In the present study, based on the primary temperament components identified in the Australian Temperament Project, these three dimensions were operationalised as follows: (1) negative reactivity (hereafter “reactivity”), which represents how intensely a child responds to frustration, and encompasses irritability and negative affect; (2) approach-sociability, which is the tendency of a child to be uninhibited or outgoing in new situations and when meeting new people (cf. daring; Lahey et al., 2008); and (3) persistence, which is the extent to which a child can stay on-task and control their attention, despite distractions and difficulties (Sanson, Hemphill, & Smart, 2004; Sanson & Oberklaid, 2013; Sanson, Prior, Oberklaid, Garino, & Sewell, 1987; Smart & Sanson, 2005). Temperamental traits influence the development of behavioural and socio-emotional adjustment (Putnam et al., 2002), and their emergence in infancy and stability by early childhood (Sanson et al., 2004; Smart & Sanson, 2005) highlight their potential utility for early detection and intervention in order to prevent psychopathology.

A substantial body of research has examined how early childhood temperament relates to subsequent internalizing and externalizing problems throughout childhood and adolescence. Convergent findings indicate that high levels of reactivity in childhood predict high levels of the broad categories of both internalizing (Letcher, Smart. Sanson, & Toumbourou, 2009; Smart, Hayes, Sanson, & Toumbourou, 2007) and externalizing symptoms (Muris, Meesters, & Blijlevens, 2007; Sanson et al., 2004; Smart et al., 2007; Young Mun, Fitzgerald, Von Eye, Puttler, & Zucker, 2001). This is consistent with the finding that negative affect represents a broadband risk factor for psychopathology (e.g., Lahey, van Hulle, Singh, Waldman, & Rathouz, 2011; Tackett et al., 2013).

In contrast, approach-sociability differentiates between internalizing and externalizing, whereby low levels of approach-sociability predict fearfulness, social withdrawal, behavioural avoidance, and correspondingly high internalizing symptoms (Leve, Kim, & Pears, 2005; Prior, Smart, Sanson, & Oberklaid, 2000b; Putnam & Stifter, 2002; Sanson et al., 2004; Young Mun et al., 2001), but act as a protective factor for the development of externalizing problems (Smart & Sanson, 2005; Schwartz, Snidman, & Kagan, 1996). Similarly, the inverse may also be true, as high levels of approach-sociability have been found to predict fearlessness, impulsivity, and risk-taking, and thus act as a risk factor for externalizing problems (e.g., Degnan et al., 2011; Hane, Fox, Henderson, & Marshall, 2008; Stifter, Putnam, & Jahromi, 2008). This pattern of results has been replicated in behavioural genetic research that has found high reactivity to explain the overlap between internalizing and externalizing domains, and act as a broad heritable vulnerability, whereas approach-sociability differentiates between the constructs (Lahey et al., 2008; Rhee, Lahey, & Waldman, 2015; Sanson et al., 2004).

The third temperamental trait —persistence— refers to the regulatory component of temperament, specifically the extent to which a child can stay on task and control their attention, despite distractions and difficulties (Sanson & Oberklaid, 2013). There is some evidence that persistence is related to lower levels of externalizing behaviours, likely through the higher levels of attention regulation that characterise the trait (Leve et al., 2005; Muris et al., 2007; Sanson et al., 2004; Smart et al., 2007; Young Mun et al., 2001). Limited research has also found indications of interactions among the three traits. For example, high reactivity and low persistence may interact to predict particularly high levels of internalizing and externalizing problems through a combination of negative affect and behavioural dysregulation (Muris et al., 2007; Sanson et al., 2004). Further, low approach and high persistence may interact to predict particularly high internalizing problems due to an inability to shift attention away from a focus on negative and/or fearful cognitions (White, McDermott, Degnan, Henderson & Fox, 2001).

Research to date has largely focused on how temperament traits relate to the broad factors of internalizing and externalizing behaviours, as reviewed above. Considerably less is known about the associations among characteristics of temperament and the development of specific psychopathology symptom profiles. However, a model that highlights specificity in relationships among temperamental characteristics and four of the core domains of child psychopathology (i.e., conduct disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], depression, and anxiety; cf. Lahey et al., 2004) has been proposed (Lahey et al., 2008; Lahey & Waldman, 2003, 2005). Lahey et al. (2008) hypothesised that levels of approach-sociability may have differential relationships with these domains of psychopathology where high levels are an underlying factor for externalizing problems —particularly for conduct disorder— and low levels are characteristic of children with anxiety. In contrast, depression is not related to approach-sociability in their proposed model. They also suggested that all four of these domains of common psychopathology are etiologically related to high reactivity, which acts as a general risk factor for all psychopathology.

Existing research is broadly consistent with this model (Rhee et al., 2015; Sanson et al., 2004). For example, a cross-sectional analysis of the data used in the present study found that lower persistence and higher reactivity were related to hyperactivity and aggression; and higher reactivity and lower approach-sociability were related to anxiety (Smart & Sanson, 2005). Other studies have found that high reactivity and low persistence are associated with ADHD (Rabinovitz, O’Neill, Rajendran, & Halperin, 2016); that low approach in early childhood predicts depression in early adulthood (Caspi, Moffitt, Newman, & Silva, 1996); that low persistence in early childhood predicts antisocial personality disorder in adulthood (Caspi et al., 1996); and that behavioural inhibition —which has many shared traits with low approach-sociability— predicts the development of social anxiety in particular (e.g., Clauss & Blackford, 2012; Rapee, 2014). However, most research to date has been limited by its focus on the role of a single temperamental trait and/or on a single domain of psychopathology. Further, there are substantial levels of overlap among temperament characteristics and between domains of psychopathology (e.g., Lahey et al., 2004; McClowry, 2002). No studies to date have accounted for the overlap within and between these domains simultaneously, and as such it is not clear which relationships represent a unique link between temperament and psychopathology, and which represent the common variance among these constructs.

The aim of the present study was therefore to determine how three core temperamental traits assessed in early childhood uniquely predicted the development of specific symptom profiles of psychopathology across childhood and early adolescence. Our hypotheses were largely based on the model proposed by Lahey and colleagues (Lahey et al., 2008; Lahey & Waldman, 2003, 2005): We expected to find that high reactivity would act as a general risk factor for psychopathology, and approach-sociability would differentiate between the development of conduct disorder and anxiety symptoms in particular. We also expected low persistence to be related to higher levels of externalizing (i.e., conduct disorder and ADHD) symptoms, in line with existing research (Leve et al., 2005; Muris et al., 2007; Sanson et al., 2004; Smart et al., 2007; Young Mun et al., 2001). We used data from a prospective longitudinal study in a nationally representative sample to examine the direct effects and interactions among temperamental traits to explore whether specific combinations of traits are stronger predictors of subsequent psychopathology. While studies to date have not found systematic gender differences in the relationships among temperament traits and domains of psychopathology, there are known gender differences in the distributions of temperamental traits and internalizing and externalizing psychopathology (Else-Quest, Hyde, Goldsmith, & Van Hulle, 2006; Lahey, 2004). To account for the possible effects of these differences, we also examined whether gender moderates these relationships.

Method

Sample

The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) led by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (Soloff, Lawrence, & Johnstone, 2005) has a multiple cohort cross-sequential design, and is based on stratified two-stage cluster sampling (i.e., first selecting postcodes then children from the Australian Medicare database). Data were collected from across all states and territories in Australia every two years starting in 2004. The present study focuses on the first five waves of data from the older cohort of children (n = 4983; 50% response rate at Wave 1), who were born between March 1999 and February 2000 (i.e., aged 4–5 years at Wave 1, and 12–13 years at Wave 5). At Wave 1, this cohort was 51.2% male. The majority of study children (85.6%) were living in a two-parent family where 82.4% of fathers and 14.0% of mothers worked full time; 63.5% of study children had at least one parent who had finished secondary school; 88.5% had at least one sibling; and 63.7% lived in a metropolitan area. Most (95.8%) of the study children were born in Australia (3.9% identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander); and 74.0% of mothers and 72.1% fathers were born in Australia (2.8% and 1.9%, respectively, identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander). The most common main languages spoken by the study child at home, excluding English (86.0% of the sample), were Southern European languages (2.5%), East Asian languages (2.4%), and South-West and Central Asian languages (2.1%). At Wave 1, 4966 children (99.7% of the full cohort) had data for the constructs of interest, and 3760 (95.0% of the full sample at Wave 5) remained in the study and had data for the constructs of interest at Wave 5, which represents a 75.7% retention rate1.

Procedures

Study informants provided informed consent, and included the child (when age-appropriate), parents (resident and non-resident), carers, and teachers. Methods of data collection included face-to-face interviews undertaken by trained professional interviewers (i.e., from a social market research company and/or the Australian Bureau of Statistics), questionnaires, observations, and direct assessment, all of which were completed in the study child’s home. For the purposes of the present study, information on the study child was primarily derived from the interview and questionnaire responses of the primary caregiver at each of the five waves. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the Australian Institute of Family Studies. For a more detailed description of the study and methods, see Soloff, Lawrence and Johstone (2005).

Assessment

Psychopathology Symptoms

In order to delineate change in psychopathology symptoms over time, we required constructs that were measured consistently across the five waves of data collection (Little, 2013). The two relevant measures that were administered across all five waves were the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997), and the Parent’s Evaluation of Development Status: Authorised Australian version (PEDS-A; Glascoe, 2000). The SDQ is a 25-item measure of behavioural and emotional problems for children aged 4–16 that has been shown to have good specificity identifying individuals with psychiatric diagnoses (Goodman, Ford, Simmons, Gatward, & Meltzer, 2000). Items are rated on a three-point scale from not true (1) to certainly true (3), and the subscales include emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behaviour. The PEDS-A is a 21-item questionnaire designed to measure parent perceptions of developmental and behavioural problems. Items are rated on a five-point scale from never (1) to almost always (5), and the subscales include emotional functioning, social functioning, school functioning, and physical functioning. The emotional symptoms subscale of the SDQ and the emotional functioning scale of the PEDS together include five items that assess fears, worries, or anxiousness (hereafter referred to as anxiety symptoms; i.e., “many worries or often seems worried”, “nervous or clingy in new situations, easily loses confidence”, “many fears, easily scared”, “problems feeling afraid or scared”, and “problems with worrying”), and two items that assess sadness or low mood (hereafter referred to as depression symptoms) (i.e., “often unhappy, depressed, or tearful”, and “problems with feeling sad or blue”). The utilisation of these items is described in more detail in the Results section. The existing five-item SDQ subscales for conduct problems (e.g., “often lies or cheats”) and hyperactivity/inattention (e.g. “constantly fidgeting or squirming) were standardised to operationalise symptoms of conduct disorder and ADHD at each time point. These scales have been shown to have good construct and diagnostic validity for conduct disorder and ADHD (e.g., Croft, Stride, Maughan, & Rowe, 2015; He, Burstein, Schmitz, & Merikangas, 2013), and had acceptable internal consistency that increased with age in the current sample2 (α = .61 to .76 and α = .74 to .80, respectively).

Temperament

The temperament of the study child was measured using an abridged version of the Toddler Temperament Scale (TTS; Prior, Sanson, Smart, & Oberklaid, 2000a). The shortened TTS in LSAC uses four items for each of the following scales: reactivity (e.g., “if upset it is hard to comfort him/her”; α = .65), persistence (e.g., “likes to complete one task before going on to the next”; α = .78), and approach-sociability (e.g., “will approach unknown children in parks to join in play”; α = .81), with each item rated on a six-point scale. The total score for each trait ranges from 1–6, but these scores were scaled to range from 0–5 to generate meaningful regression coefficients.

Data Analysis

Latent class growth analyses (LCGAs) were performed using MPlus version 7 (as described below), and all other analyses were completed using SPSS version 22. Sample weights were used in all analyses. A conservative significance level of α = .005 was used to account for the large sample size and multiple comparisons. There were three phases of data analysis: 1) constructing composite scores for depression and anxiety, based on the available items; 2) delineating trajectories of symptom change over time in anxiety, depression, conduct disorder, and ADHD; and 3) investigating the temperament precursors to the psychopathology symptom trajectories at ages 4–5 years, as well as their interactions and the role of gender. The specific methods used in each phase of analysis are described along with the results below.

Results

Constructing composite scores for depression and anxiety

The item total correlations (ITCs), squared multiple correlations (SMCs), and internal consistency (α) among the five anxiety items increased with the age of the study children. Across the five waves, the SDQ item of “nervous or clingy in new situations, easily loses confidence” had the weakest relationships with the other four items (ITCs < .5 and SMCs < .3) and was consequently not retained to operationalise anxiety. The remaining four items had reasonable internal consistency across the five waves (α = .68 to α = .81). The items were standardised and averaged to form an anxiety score at each time point.

Similarly, the ITCs and Cronbach’s alphas between the two depression items increased with the age of the study children, from r = .22 (p < .0005) and α = .36 at ages 4–5 to r = .52 (p < .0005) and α = .68 at ages 12–13. The items evidently measure separate but related constructs, so were both retained to operationalise depressive symptoms. The items were standardised and averaged to form a depression score at each time point3.

Delineating Symptom Trajectories for Ages 4–5 to 12–13

The symptom measures at each wave for anxiety, depression, conduct disorder, and ADHD were used to run four separate LCGAs (one for each symptom domain) based on the recommendations of Berlin, Parra and Williams (2013) and Jung and Wickrama (2008). These analyses model participants’ symptom change over time to detect latent groups (or “classes”) of symptom levels and change. Individuals are classified into latent classes based upon similar patterns of data. This is a complex process, but to briefly summarise, single class latent growth curve models were run to determine which parameters should be used in the model (i.e., intercept, slope, quadratic, and/or cubic terms). LCGAs were subsequently run within each parameterisation that provided good model fit (see Supplementary Table S1), starting with a single class and adding additional classes one at a time until the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test reached non-significance (p > .05). This indicates that the previous model (i.e., with one fewer class, referred to as the “k-1” class model) is the best model within that parameterisation. Finally, the best overall model is identified by comparing these “k-1” class models across the parameterisations (e.g., comparing the strongest model with an intercept and a slope versus the strongest model with an intercept, a slope, and a quadratic term), and selecting the model with the lowest Bayesian information criterion.

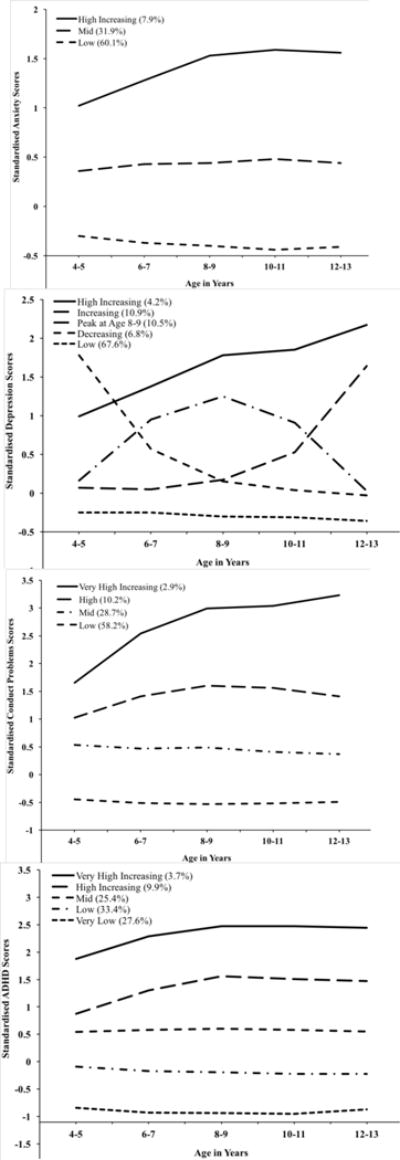

In all cases, the strongest model included an intercept, slope, and quadratic term (see Supplementary Table S2 for detailed information on the intercept, slope, and quadratic terms in each model). The anxiety, conduct disorder, and ADHD symptom trajectories were all similar (see Figure 1): The three classes that best captured change in anxiety symptoms over time represented groups of participants with three different levels of symptom severity. The high-symptom group increased in relative severity over time, and the low-symptom group included the large majority of participants. The four groups of conduct disorder symptoms represented four different levels of symptom severity. Three of the four conduct groups were stable over time, although the highest symptom group was characterised by increasing relative severity over time; the low symptom group included the large majority of participants. Mirroring this pattern, the five classes that best captured change in ADHD symptoms over time were generally stable, and represented groups with five different levels of symptom severity —from very high and increasing to very low. In contrast, the five classes that characterised different trajectories of change in depressive symptoms over time were more varied. As for the other types of symptoms, there was a stable, low symptom group and a high symptom group that increased in relative severity. However, three groups showed unique patterns: One began with especially severe symptoms at age 4–5 that quickly returned to population levels; another showed relatively low symptoms across most of childhood, but showed a rapid rise in severity around puberty; and a third group showed increased severity across early childhood, but their symptoms peaked at age 8–9 years and then decreased again.

Fig 1.

Symptom trajectories from ages 4–5 to 12–13 years for anxiety (top left), depression (top right), conduct disorder (bottom left), and ADHD (bottom right). Scores for each domain are standardised within wave to highlight individuals’ relative severity at each age. The standardised scores represent standard deviations above or below the mean at each of the five time points.

Individuals’ class membership was saved for each of the four LCGAs, resulting in four symptom trajectory variables. In all subsequent analyses, the lowest symptom class was treated as the reference category; the labels used to refer to each group are shown in Figure 1. There was substantial overlap between the four symptom trajectory variables. For example, of the individuals who fell into the lowest symptom class for at least one of the LCGAs (n = 4292), 80.7% fell into the lowest symptom class for two or more disorders, 52.2% fell into the lowest symptom class for three or more disorders, and 20.9% fell into the lowest category for all four disorders. Of the individuals who fell into the highest symptom class for at least one of the LCGAs (n = 567), 28.4% fell into the highest symptom class for two or more disorders, 6.7% fell into the highest category for three or more disorders, and 1.9% fell into the highest category for all four disorders. These rates are much higher than would be expected by chance. For example, based on the proportion of individuals in the highest symptom category for each disorder, we would expect less than one thousandth of a per cent (0.0004%) of the sample to fall in the highest category for all four disorders by chance; the rate in our sample is 54 times higher than the chance level of co-occurrence. We consequently accounted for these high rates of co-occurrence in all subsequent analyses, as described below.

Investigating Temperament Precursors to Symptom Trajectories

We ran multivariate ordinal and multinomial logistic regressions to examine how gender and parent-reported child temperament characteristics (i.e., reactivity, persistence, and approach-sociability) at age 4–5 interacted to predict the study child’s subsequent symptom trajectories for each domain of psychopathology (i.e., anxiety, depression, conduct disorder, and ADHD), after controlling for other presenting symptoms. For example, we examined the unique effect of each temperament characteristic in predicting anxiety symptom trajectories, controlling for whether the child was in a symptomatic class for depression, conduct disorder, and/or ADHD. To do this, we created a dichotomous “symptomatic” variable for each domain of psychopathology, coded as yes or no, depending on whether an individual fell in a symptomatic trajectory, or the reference group (i.e., the group with the lowest symptom levels), respectively. This was to account for the high rates of overlap among the symptomatic trajectories, and to delineate the unique relationships among each temperament characteristic and domain of psychology.

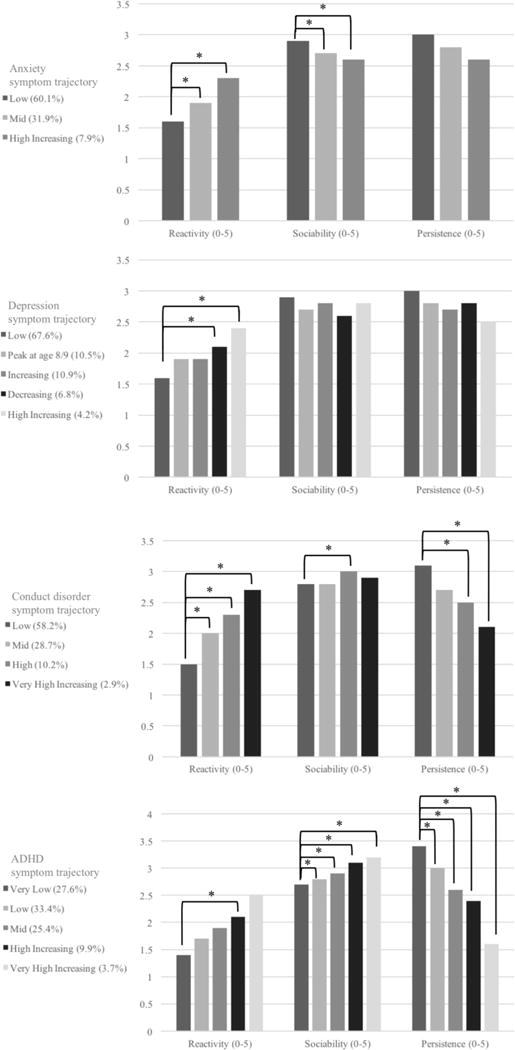

Ordinal regression was used for the anxiety analyses. Multinomial regression was used for the depression analyses, given the nature of the trajectories. The parallel odds assumption of ordinal regression was violated for the hyperactivity/inattention and conduct problems analyses, so multinomial regression was also used for these analyses. Interaction effects among temperament characteristics, and for gender with each of the temperament traits, were examined in each set of analyses, but did not reach significance in any of the models. Nagelkerke Pseudo R2 values were used to approximate the variance accounted for by the main effects of the temperament and socio-demographic variables in each model. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics within each symptom trajectory group at ages 4–5, and includes a summary of the significant effects in the regression analyses; Figure 2 depicts the observed means of the temperament constructs in each symptom profile.

Table 1.

Observed Descriptive Statistics within Each Symptom Trajectory Group at Ages 4–5. Mean (standard deviation) or N (%).

| Symptom Group (% of sample) | Gender —Male | Temperament Trait (Range)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactivity (0–5) | Approach-Sociability (0–5) | Persistence (0–5) | ||

|

|

|

|||

| Full Sample | 2553 (51.2%) | 1.7 (.93) | 2.8 (1.22) | 2.9 (.97) |

| Anxiety | ||||

| Low (60.1%) | 1500 (51.7%) | 1.6 (.87) | 2.9 (1.19) | 3.0 (.93) |

| Mid (31.9%) | 764 (51.0%) | 1.9 (.94)* | 2.7 (1.24)* | 2.8 (.97) |

| High Increasing (7.9%) | 180 (52.5%) | 2.3 (1.08)* | 2.6 (1.31)* | 2.6 (1.09) |

| Depression | ||||

| Low (67.6%) | 1733 (51.2%) | 1.6 (.87) | 2.9 (1.21) | 3.0 (.94) |

| Decreasing (6.8%) | 159 (53.2%) | 2.1 (1.04)* | 2.6 (1.25) | 2.8 (.96) |

| Peak at age 8/9 (10.5%) | 241 (52.7%) | 1.9 (.95) | 2.7 (1.26) | 2.8 (1.01) |

| Increasing (10.9%) | 223 (51.0%) | 1.9 (.95) | 2.8 (1.21) | 2.7 (1.03) |

| High Increasing (4.2%) | 90 (50.8%) | 2.4 (1.03)* | 2.8 (1.27) | 2.5 (1.06) |

| Conduct Problems | ||||

| Low (58.2%) | 1398 (46.8%) | 1.5 (.82) | 2.8 (1.23) | 3.1 (.91) |

| Mid (28.7%) | 770 (54.8%) | 2.0 (.92)* | 2.8 (1.21) | 2.7 (.93) |

| High (10.2%) | 295 (65.0%)* | 2.3 (.95)* | 3.0 (1.22)* | 2.5 (1.06)* |

| Very High Increasing (2.9%) | 88 (66.7%)* | 2.7 (1.11)* | 2.9 (1.17) | 2.1 (1.02)* |

| Hyperactivity/Inattention | ||||

| Very Low (27.6%) | 488 (35.9%) | 1.4 (.84) | 2.7 (1.25) | 3.4 (.79) |

| Low (33.4%) | 816 (47.9%)* | 1.7 (.87) | 2.8 (1.22)* | 3.0 (.85)* |

| Mid (25.4%) | 799 (61.2%)* | 1.9 (.91) | 2.9 (1.76)* | 2.6 (.93)* |

| High Increasing (9.9%) | 305 (70.4%)* | 2.1 (1.05)* | 3.1 (1.22)* | 2.4 (.92)* |

| Very High Increasing (3.7%) | 143 (81.3%)* | 2.5 (1.16) | 3.2 (1.26)* | 1.6 (.99)* |

Note.

Indicates a significant group difference (p < .005) from the reference group (lowest symptom group) within a temperament trait in the full regression models, which were run separately for each domain of psychopathology.

Fig 2.

Observed means of the temperament traits at age 4–5 within each symptom profile for anxiety, depression, conduct disorder, and ADHD.

* Indicates a significant group difference (p < .005) in the full regression models, which were run separately for each domain of psychopathology.

Anxiety

Higher levels of reactivity and lower levels of approach-sociability were significantly related to an increase in the odds of being in higher anxiety symptom trajectories. The effect of a one-point increase in reactivity, Exp(B) = 1.24, p < .0005, was similar to the effect of a one-point decrease in approach-sociability, Exp(B) = 1.23, p < .0005. Persistence was not a significant predictor of symptom trajectory membership (p = .121), and neither was gender (p = .048) given our alpha level of .005. The three temperamental traits accounted for 7.9% of the variance in anxiety symptom trajectory group membership.

Depression

Reactivity predicted depression symptom trajectory membership, but persistence and approach-sociability were not significant predictors (p = .638 and p = .591, respectively). A one-point increase in reactivity was related to 1.53 and 1.55 higher odds (ps < .0005) of being in the decreasing and high-increasing groups, respectively. This effect suggests that reactivity predicted the starting values of the trajectories, but was not related to elevated symptoms over time. Gender was not a significant predictor of symptom trajectory group (p = .171). Temperament accounted for 7.4% of the variance in depression symptom trajectory membership.

Conduct Disorder

Higher levels of reactivity, lower levels of persistence, and higher levels of approach-sociability were significantly related to symptom trajectory group membership. A one-point increase in reactivity had the strongest effect, predicting a 1.82 to 3.11 increase in odds of being in a higher symptom group, compared to the low symptom group (ps < .0005). A one-point decrease in persistence was related to a 1.28 and 1.66 increase in the odds of being in the high and very high increasing symptom groups, respectively, compared to the low symptom group (ps < .0005), but did not predict group membership for the mid symptom group (p = .039). A one-point increase in approach-sociability was related to a 1.24 increase in odds of being in the high symptom group, compared to the low-symptom group (p < .0005), but did not predict group membership in the mid or very high increasing symptom level groups. Gender was also a significant predictor of group membership, where boys had 1.76 (p < .0005) and 1.96 (p = .004) higher odds of being in the high and very high increasing trajectories, respectively. Temperament accounted for 18.9% of the variance in conduct disorder symptom trajectory membership.

ADHD

As for conduct problems, higher levels of reactivity, lower levels of persistence, and higher levels of approach-sociability were significantly related to greater odds of being in the higher symptom groups. A one-point increase in reactivity had the smallest effect, predicting a 1.52 increase in the odds only for being in the high symptom group, compared to the low-symptom group (p < .0005). A one-point decrease in persistence had the strongest effect, predicting a 1.93 to 7.81 increase in the odds of being in any symptomatic group, compared to the low-symptom group (ps < .0005). A one-point increase in approach-sociability was also related to a 1.11 (p = .002) to 1.63 (p < .0005) increase in the odds of being in the symptomatic groups, compared to the low-symptom group. Gender was a strong predictor of group membership, where boys had 1.74 to 8.74 times higher odds of being in a symptomatic group (ps < .0005). Temperament accounted for 24.3% of the variance in ADHD symptom trajectory membership.

Discussion

This study examined the predictive validity of early childhood temperament for the development of psychopathology symptoms across childhood and adolescence. By accounting for the overlap within these domains, we identified the unique predictive relationships between temperament and subsequent specific forms of symptomatology. Taken together, the results suggested that three core temperamental characteristics (i.e., reactivity, approach-sociability, and persistence) differentially predicted the patterns of depression, anxiety, conduct disorder, and ADHD symptoms across childhood and early adolescence.

Reactivity in early childhood uniquely predicted higher symptom levels for all domains of psychopathology, as expected. Higher levels of reactivity were related to higher relative levels of anxiety, depression, conduct disorder, and ADHD symptoms even after controlling for levels of approach-sociability and persistence, and for the overlap among the domains of psychopathology. This finding is consistent with existing research showing that reactivity is a heritable broadband risk factor for psychopathology (cf. negative affect; Caspi et al., 2014; Lahey et al., 2008). It also strengthens that argument by highlighting that this relationship holds for each of the four core domains of common childhood psychopathology even after accounting for other presenting symptoms. This finding has important implications for early identification and intervention, given reactivity can be measured reliably from as early as one month of age (Rothbart, 1989).

In contrast to the global risk factor of high reactivity, approach-sociability differentiated between the four domains of psychopathology, in line with Lahey et al.’s (2008) hypotheses. Higher levels of approach-sociability uniquely predicted more severe trajectories for conduct disorder and ADHD symptoms, and predicted less severe symptom trajectories for anxiety, as expected (e.g., Prior et al., 2000b). Consistent with prediction, approach-sociability was not related to depression symptom trajectories (Lahey et al., 2008). However, in contrast to their hypotheses, conduct disorder was not particularly strongly related to approach-sociability after controlling for other temperamental characteristics and co-occurring domains of psychopathology. Instead, ADHD symptoms had the most robust relationship with approach-sociability. This may be because approach-sociability captures high positive approach (i.e., exuberance), and not high negative approach (i.e., high anger proneness); Nigg, Goldsmith and Sachek’s (2004) model of temperament in ADHD specifies that high negative approach in ADHD is associated with comorbid conduct disorder, but high positive approach is not associated with comorbid disorder presentation. To clarify these relationships, future research should examine whether conduct disorder is uniquely associated with different conceptualisations of approach, withdrawal, or daring, after controlling for presenting ADHD symptoms.

The third temperament trait assessed in this study —persistence— was inversely related to both externalizing domains. This effect was strongest for ADHD, as expected, given that problems regulating attention are the defining characteristic of the disorder. However, the fact that low persistence also predicted higher conduct disorder symptoms, even when controlling for symptoms of ADHD, points to the importance of this temperamental trait in predicting the development of non-attentional externalizing problems as well (cf. Muris et al., 2007; Sanson et al., 2004; Smart et al., 2007; Young Mun et al., 2001). In contrast, persistence was not significantly related to depressive or anxiety symptoms. Hence it appears that the poor concentration and selective attentional focus that are characteristic of anxiety and depression (Hallion & Ruscio, 2011) may stem from bases such as low inhibitory control, which is the ability to suppress a dominant response or behaviour in favour of a more appropriate response or behaviour (cf. White et al., 2011), rather than the attentional difficulties characteristic of ADHD.

We did not find any other significant relationships beyond these direct associations between temperament characteristics and domains of psychopathology. For example, the three temperamental traits did not interact to differentially predict symptom presentation. This was in contrast with past research that focused on broad domains of psychopathology or individual disorders (e.g., Lahat, Hong, & Fox, 2011; Muris et al., 2007; Sanson & Smart, 2004; White et al., 2011), and highlights that each temperamental trait had a unique and additive predictive role for the development of subsequent psychopathology symptoms, rather than having conditional effects on each other (e.g., high reactivity did not amplify the effect of low persistence to predict particularly high levels of internalizing and externalizing symptoms; cf. Muris et al., 2007; Sanson & Smart, 2004).

Similarly, gender did not moderate the role of any of the temperament traits. This is consistent with the body of research that has found boys and girls have similar symptom trajectories (Letcher et al., 2009; Sterba, Prinstein, & Cox, 2007), and similar relationships between temperament and psychopathology (Oldehinkel, Hartman, De Winter, Veenstra, & Ormel, 2004). Gender was, however, related to externalizing symptom trajectory membership, where boys were more likely to have higher symptom levels. In fact, the group with the highest symptoms of ADHD was 81% male. This is also consistent with research that has found boys and girls to differ in their distribution between symptom trajectories (e.g., Oldehinkel et al., 2004). We might have expected to find more girls in the increasing depressive symptom trajectory (cf. Leve et al., 2005), but this gender difference may not be evident until after early adolescence (Hankin & Abramson, 2001).

Overall, there was marked consistency in the symptom trajectories for anxiety, conduct disorder, and ADHD. The stability of the symptoms in these domains is consistent with their early ages of onset (Kessler et al., 2005) and highlights the significance of presenting symptoms from early childhood onwards. Further, the size and overlap of the highest symptom severity groups for each disorder was similar to the prevalence and comorbidity rates found in the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (Lawrence et al., 2015). This gives us confidence that the symptom trajectories have validity, and may indicate a lifetime risk for subsequent psychopathology (Kessler et al., 2005). As such, our ability to predict these symptom groups from early-emerging temperament could have long term clinical significance.

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

The strengths and weaknesses of the study should be kept in mind when interpreting these results. The primary strength of this study was the use of data from a nationally representative prospective longitudinal sample of nearly 5,000 children. A related limitation was measurement, as the study relied on just two to five items to operationalise the core constructs in the study. For example, there is limited information regarding the construct validity of Toddler Temperament Scale (e.g., Rapee, Kennedy, Ingram, Edwards, & Sweeney, 2005; Sanson, Pedlow, Cann, Prior, & Oberklaid, 1996), and this should be addressed in future research. In particular, the results regarding the trajectories of change in depressive symptoms should be interpreted with caution, as the two items that were combined to indicate the construct did not have strong psychometric properties, and three of the five symptom trajectories had marked differences from the other domains of psychopathology. We included the depressive symptom trajectories despite these limitations, as we believed that the benefit of including the four core domains of childhood psychopathology in the analyses (cf. Lahey et al., 2004) outweighed the negatives.

The fact that primary caregivers reported both child temperament and psychopathology symptoms also introduces potential rater bias. For example, parent psychopathology confounds the measurement of child psychopathology, as it affects parent perceptions of child behaviour, and confers both genetic and environmental risk for the development of psychopathology (e.g., De los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005; Ordway, 2011). However, existing research suggests that parent reports of behaviour can identify coherent temperament domains that originate early in life to influence adjustment (Toumbourou, Williams, Letcher, Sanson, & Smart, 2011), and have validity in long term prediction (Rapee, 2014; Schwartz et al., 1996). Regardless, future studies should incorporate multiple informants, and observational and physiological measures to capture the variables of interest with greater reliability and validity.

It was also clear that temperament was only one of a number of risk factors for the development of psychopathology, as it explained only a modest amount of variance in trajectory group membership (7–24%). ADHD had the most robust relationship with temperamental traits, and this is likely related to the fact that it has the youngest age of onset (Kessler et al., 2005), as well as a marked conceptual overlap between ADHD symptoms and temperamental traits (Nigg et al., 2004). As such, another limitation of this study was its focus on the direct intra-individual relationships between temperament and psychopathology, without accounting for the complex interactional and transactional relationships that temperament has with the environment (Putnam et al., 2002). For example, although temperament is thought to be innate, it has already been shaped in infancy by the prenatal and postnatal environment (O’Donnell, Glover, Barker, & O’Connor, 2014). More broadly, the fit of a child to their environment, their susceptibility to environmental influence, and the capability and parenting style of their caregivers will all interact with both genes and temperament to shape the risk and expression of specific psychopathology symptoms, as well as responsiveness to interventions (Belsky & Pluess, 2009; Pluess & Belsky, 2010). We consequently acknowledge that the results of the present study indicate temperament is one risk/protective factor that makes up part of a larger cumulative risk for psychopathology (cf. Busseri, Willoughby, & Chalmers, 2006; Forbes, Tackett, Markon, & Krueger, 2016).

Implications and conclusions

Our study adds to the literature by fostering a more nuanced understanding of the unique roles of temperament in predicting the emergence of four domains of common psychopathology across the lifespan. Given each of the four domains of psychopathology we investigated are developmentally coherent into adulthood (see Forbes et al., 2016, for a review), our results have important implications for the early detection and prevention of childhood psychopathology, allowing us to interrupt maladaptive pathways before they develop into increasingly severe forms of psychopathology (cf. Beauchaine & McNulty, 2014). Taken together, these results suggest that temperament is an early identifiable risk factor for the development of psychopathology. As such, once unique temperament constellations of risk are identified, steps can be taken to ameliorate the risks by introducing parenting interventions that can moderate the trajectory of the psychopathology symptoms (Rapee, 2013).

While this study examines prediction from pre-school age, reactivity problems are readily identified in infancy. Indeed irritability and inconsolable crying are the most common reasons parents of infants present to health professionals (Oberklaid, 2000) and there is a growing body of evidence that reactive temperament in infancy is a phenotypic marker of differential susceptibility to a more responsive caregiving environment (Belsky & Pluess, 2013; Pluess & Belsky, 2010; Mesman et al., 2009). Intervening at the earliest possible opportunity when problems and perceptions may be more remediable can, therefore, lead to a more positive developmental trajectory for the whole family, a positive foundation for the child’s physical, social-emotional and cognitive development, and significant health savings to the community (Heckman, 2012; Shonkoff & Fisher, 2013).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part a National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) training grant supporting the work of Miriam Forbes (T320A037183). NIDA had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in writing; nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children is conducted in partnership between the Department of Social Services, the Australian Institute of Family Studies, and the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Footnotes

Attrition in LSAC has been examined in detail elsewhere (Cusack & Defina, 2013), and the bias in our study due to attrition was reduced by applying survey weights. However, these weights are based on demographic representativeness and do not necessarily account for differential drop-out with regard to the measures under investigation. As such, we analysed the symptom levels for each domain of psychopathology at Wave 1 for participants who dropped out of the study compared to participants who continued on to Wave 5. While there were no significant differences between the groups in symptom levels of anxiety, t(1871.44) = .28, p = .782; Cohen’s d < .01, or depression, t(1802.50) = 1.95, p = .052; Cohen’s d = .07, there were small but significant differences in symptoms of conduct disorder, t(1986.44) = 5.22, p < .001; Cohen’s d = .17, and ADHD, t(2027.30) = 6.04, p < .001; Cohen’s d = .20. In short, participants who dropped out tended to have higher externalizing symptoms on average, but the small effect sizes highlight that the two groups have more than 92% overlap in the distribution of these symptoms.

None of the scales used in the present study had excellent internal consistency. However, given the scales all represent abbreviated measures of complex constructs, we would expect moderate internal consistency at best, given the heterogeneous item content required to achieve content validity (i.e., substantial item specific variance) and the small number of items (i.e., two to five) included in each scale.

The use of standardised scales to represent the four domains of psychopathology at each time point highlights individuals’ relative symptom severity at each wave (i.e., the number of standard deviations away from the population mean), rather than absolute changes in symptom severity. This reflects a statistical deviation conceptualisation of psychopathology, and prevents population level age-related changes between waves from obscuring individual differences.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

References

- Beauchaine TP, McNulty T. Comorbidities and continuities as ontogenic processes: Toward a developmental spectrum model of externalizing psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25:1505–1528. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:885–908. doi: 10.1037/a0017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin KS, Parra GR, Williams NA. An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 2): Longitudinal latent class growth analysis and growth mixture models. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2014;39:188–203. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busseri MA, Willoughby T, Chalmers H. A rationale and method for examining reasons for linkages among adolescent risk behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;36:279–289. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9105-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Goldman-Mellor SJ, Harrington H, Israel S, Moffitt TE. The p factor one general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clinical Psychological Science. 2014;2:119–137. doi: 10.1177/2167702613497473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders. Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:1033–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110071009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss JA, Blackford JU. Behavioral inhibition and risk for developing social anxiety disorder: A meta-analytic study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51:1066–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Peeke LG, Martin JM, Truglio R, Seroczynski AD. A longitudinal look at the relation between depression and anxiety in children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:451. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft S, Stride C, Maughan B, Rowe R. Validity of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire in preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e1210–e1219. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusack B, Defina R. The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children technical paper No 10 Wave 5 weighting and non-response. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Institute of Family Studies; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Hane AA, Henderson HA, Moas OL, Reeb-Sutherland BC, Fox NA. Longitudinal stability of temperamental exuberance and social-emotional outcomes in early childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:765–780. doi: 10.1037/a0021316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:483. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM, Hyde JS, Goldsmith HH, Van Hulle CA. Gender differences in temperament: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:33. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes MK, Tackett JL, Markon KE, Krueger RF. Beyond comorbidity: Toward a dimensional and hierarchal approach to understanding psychopathology across the lifespan. Development and Psychopathology. 2016;28:971–986. doi: 10.1017/S0954579416000651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glascoe FP. Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status: Authorized Australian version. Centre for Community Child Health, Parkville 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, Ford T, Simmons H, Gatward R, Meltzer H. Using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to screen for child psychiatric disorders in a community sample. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;177:534–539. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallion LS, Ruscio AM. A meta-analysis of the effect of cognitive bias modification on anxiety and depression. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137:940–958. doi: 10.1037/a0024355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hane AA, Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ. behavioral reactivity and approach-withdrawal bias in infancy. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1491–1496. doi: 10.1037/a0012855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He JP, Burstein M, Schmitz A, Merikangas KR. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): The factor structure and scale validation in U.S. adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41:583–595. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9696-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ. The developmental origins of health. Health Economics. 2012;21:24–29. doi: 10.1002/hec.1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung T, Wickrama KAS. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2:302–317. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahat A, Hong M, Fox NA. Behavioural inhibition: Is it a risk factor for anxiety? International Review of Psychiatry. 2011;23:248–257. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2011.590468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB. Commentary: Role of temperament in developmental models of psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:88–93. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, Chronis AM, Jones HA, Williams SH, Loney J, Waldman ID. Psychometric characteristics of a measure of emotional dispositions developed to test a developmental propensity model of conduct disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:794–807. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, Waldman ID, Loft JD, Hankin BL, Rick J. The structure of child and adolescent psychopathology: Generating new hypotheses. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:358. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Van Hulle CA, Singh AL, Waldman ID, Rathouz PJ. Higher-order genetic and environmental structure of prevalent forms of child and adolescent psychopathology. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:181–189. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID. A developmental propensity model of the origins of conduct problems during childhood and adolescence. In: Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, editors. Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 76–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID. A developmental model of the propensity to offend during childhood and adolescence. In: Farrington DP, editor. Integrated developmental and life-course theories of offending. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction; 2005. pp. 15–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Zald DH, Hakes JK, Krueger RF, Rathouz PJ. Patterns of heterotypic continuity associated with the cross-sectional correlational structure of prevalent mental disorders in adults. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:989–996. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, Boterhoven de Haan K, Sawyer M, Ainley J, Zubrick SR. The mental health of children and adolescents: Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Department of Health; Canberra: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Letcher P, Smart D, Sanson A, Toumbourou JW. Psychosocial precursors and correlates of differing internalizing trajectories from 3 to 15 years. Social Development. 2009;18:618–646. [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Kim HK, Pears KC. Childhood temperament and family environment as predictors of internalizing and externalizing trajectories from ages 5 to 17. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:505–520. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-6734-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little PTD. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McClowry SG. The temperament profiles of school-age children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2002;17:3–10. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2002.30929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesman J, Stoel R, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoon M, Juffer F, Koot H, Lenneke RA. Predicting growth curves of early childhood externalising problems: Differential susceptiblity of children with difficult temperament. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;37:625–636. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9298-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, Blijlevens P. Self-reported reactive and regulative temperament in early adolescence: Relations to internalizing and externalizing problem behavior and “Big Three” personality factors. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:1035–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Goldsmith HH, Sachek J. Temperament and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: The development of a multiple pathway model. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:42–53. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell KJ, Glover V, Barker ED, O’Connor TG. The persisting effect of maternal mood in pregnancy on childhood psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2014;26:393–403. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberklaid F. Persistent crying in infancy: A persistent clinical conundrum. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2000;36:297–298. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2000.00516.x. Editorial comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldehinkel AJ, Hartman CA, De Winter AF, Veenstra R, Ormel J. Temperament profiles associated with internalizing and externalizing problems in preadolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:421–440. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordway MR. Depressed mothers as informants on child behavior: Methodological issues. Research in Nursing and Health. 2011;34:520–532. doi: 10.1002/nur.20463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluess M, Belsky J. Children’s differential susceptibility to effects of parenting. Family Science. 2010;1:14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Prior M, Sanson A, Smart D, Oberklaid F. Pathways from infancy to adolescence: Australian Temperament Project 1983–2000. Australian Institute of Family Studies; Melbourne: 2000a. [Google Scholar]

- Prior M, Smart D, Sanson A, Oberklaid F. Does shy-inhibited temperament in childhood lead to anxiety problems in adolescence? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000b;39:461–468. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Sanson AV, Rothbart MK. Child temperament and parenting. Handbook of Parenting. 2002;1:255–277. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Stifter CS. Development of approach and inhibition in the first year. Parallel findings from motor behavior, temperament ratings, and directional cardiac responses. Developmental Science. 2002;5:441–451. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovitz BB, O’Neill S, Rajendran K, Halperin JM. Temperament, executive control, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder across early development. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2016;125:196–206. doi: 10.1037/abn0000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM. The preventative effects of a brief, early intervention for preschool-aged children at risk for internalising: Follow-up into middle adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:780–788. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM. Preschool environment and temperament as predictors of social and nonsocial anxiety disorders in middle adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53:320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Kennedy S, Ingram M, Edwards SL, Sweeney L. Prevention and early intervention of anxiety disorders in inhibited preschool children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:488–497. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettew DC, McKee L. Temperament and its role in developmental psychopathology. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2005;13:14–27. doi: 10.1080/10673220590923146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SH, Lahey BB, Waldman ID. Comorbidity among dimensions of childhood psychopathology: Converging evidence from behavior genetics. Child Development Perspectives. 2015;9:26–31. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK. Temperament and development. Temperament in Childhood. 1989:187–247. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK. Temperament, development, and personality. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Sanson A, Hemphill SA, Smart D. Connections between temperament and social development: A review. Social Development. 2004;13:142–170. [Google Scholar]

- Sanson A, Oberklaid F. The Australian Temperament Project: The First 30 Years. Australian Institute of Family Studies Melbourne; Australia: 2013. Infancy and early childhood. [Google Scholar]

- Sanson A, Pedlow R, Cann W, Prior M, Oberklaid F. Shyness ratings: Stability and correlates in early childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1996;19:705–724. [Google Scholar]

- Sanson A, Prior M, Oberklaid F, Garino E, Sewell J. The structure of infant temperament: Factor analysis of the Revised Infant Temperament Questionnaire. Infant Behavior & Development. 1987;10:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Snidman N, Kagan J. Early childhood temperament as a determinant of externalizing behavior in adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:527–537. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Fisher PA. Rethinking evidence based practice and two-generation programs to create the future of early childhood policy. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25:1635–1653. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart D, Hayes A, Sanson A, Toumbourou JW. Mental health and wellbeing of Australian adolescents: Pathways to vulnerability and resilience. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2007;19:263–268. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2007.19.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart D, Sanson A. A comparison of children’s temperament and adjustment across 20 years. Family Matters. 2005;72:50. [Google Scholar]

- Soloff C, Lawrence D, Johnstone R. Longitudinal Study of Australian Children technical paper No 1: Sample design. Australian Institute of Family Studies; Melbourne, Australia: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sterba SK, Prinstein MJ, Cox MJ. Trajectories of internalizing problems across childhood: Heterogeneity, external validity, and gender differences. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:345–366. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stifter CS, Putnam S, Jahromi L. Exuberant and inhibited toddlers: Stability of temperament and risk for problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:401–421. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tackett JL, Lahey BB, van Hulle C, Waldman I, Krueger RF, Rathouz PJ. Common genetic influences on negative emotionality and a general psychopathology factor in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:1142–1153. doi: 10.1037/a0034151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Chess S. Temperament and Development. Oxford, England: Brunner/Mazel; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Toumbourou JW, Williams I, Letcher P, Sanson A, Smart D. Developmental trajectories of internalising behaviour in the prediction of adolescent depressive symptoms. Australian Journal of Psychology. 2011;63:214–223. [Google Scholar]

- White LK, McDermott JM, Degnan KA, Henderson HA, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition and anxiety: The moderating roles of inhibitory control and attention shifting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:735–747. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9490-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young Mun E, Fitzgerald HE, Von Eye A, Puttler LI, Zucker RA. Temperamental characteristics as predictors of externalizing and internalizing child behavior problems in the contexts of high and low parental psychopathology. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2001;22:393–415. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.