Abstract

Objectives

This study examines the cognitive and affective dimension of pregnancy attitudes in order to better recognize the role of each in pregnancy ambivalence as well as the relative importance of each in understanding contraceptive use.

Study Design

Data from a national sample of 2,894 women aged 18–39, gathered at baseline and six months later, was used to examine a measure of pregnancy avoidance (cognitive) and a measure of happiness about pregnancy (affective), both separately and jointly. I used bivariate and multivariate analysis to examine associations between attitudinal measures and consistent contraceptive use. I also examined changes in attitudes over time and associations between changes in attitudes and changes in consistent contraceptive use.

Results

While a majority of women, 53%, indicated it was very important to avoid pregnancy, a substantially lower proportion, 23%, would have been very unhappy to be pregnant. In logistic regression models that included both measures, only pregnancy avoidance was associated with consistent contraceptive use. Cognitive attitude was less likely than affective attitude to change over time; additionally, change in pregnancy avoidance, but not happiness, was associated with changes in consistent contraceptive use.

Conclusion(s)

Pregnancy avoidance appears to play a more important role in understanding consistent contraceptive use. Findings from this study provide support for the idea that positive feelings about a pregnancy do not contradict a desire to avoid conception and that feelings and intentions may be distinct concepts for many women.

Implications

Health care providers should assess patients’ pregnancy avoidance attitude but also recognize that this can change over short period of time for some women and should be evaluated regularly.

Keywords: pregnancy attitudes, pregnancy ambivalence, contraceptive use

1. Introduction

In order to better understand factors that contribute the high levels of unintended pregnancy in the United States, a body of research examining pregnancy ambivalence has emerged. Miller, who developed the original framework to understand this construct, theorized that women’s contraceptive use depends upon an internal balance between positive and negative feelings towards pregnancy [1]. In this context, conflicting, or seemingly conflicting, feelings about pregnancy are considered to represent ambivalence.

To date, there is no standard measure of pregnancy ambivalence and a variety of researchers have taken a range of approaches. Some assess ambivalence using a single measure, for example, characterizing as ambivalent women who indicated they would be happy if they got pregnant even though they were not trying to become pregnant or did not want to have any (more) children [2,3,4]. Other studies have relied on measures of both cognitive and affective pregnancy attitudes [5] and, for example, respondents who want to avoid pregnancy (cognitive) but would nonetheless be happy, or not unhappy, if they found out they were pregnant (affective) are considered ambivalent [4,6,7,8, 9].

Perhaps not surprisingly, research of different populations relying on different measures to assess ambivalence have resulted in a range of findings. Studies suggest that a substantial proportion of women who want to avoid pregnancy express ambivalence, ranging from 23% among a nationally representative sample of U.S. women [3] to 58% among a sample of low-income women seeking pregnancy testing at a family planning clinic [4]. There is some evidence that pregnancy ambivalence changes over time. In a given week 4% of young women expressed ambivalent attitudes over a two and a half year survey period, though 18% reported ambivalence on at least one survey [7]. A number of studies have found that women who express ambivalent attitudes are less likely to be effective contraceptive users [2,3,7,8], though not all studies have confirmed this association [8,9].

Finally, an emerging body of research suggests that positive feelings about pregnancy do not contradict a desire to avoid conception. For example, several studies have found that substantial minorities of (mostly Latina) women were motivated to use highly effective contraceptive methods even though they would be happy to be pregnant [10,11,12]. Thus, feelings and intentions may represent distinct dimensions of pregnancy attitudes [10,11,12]

This study contributes to the growing body of research on pregnancy ambivalence. Using data from a national sample of women at two points in time, I examine the cognitive and affective dimensions of pregnancy attitudes, independently and jointly, and the extent to which each is associated with consistent contraceptive use. Additionally, I examine the extent to which attitudes change over a relatively short time period and their associations with changes in contraceptive use.

2. Materials and methods

Data for the analyses come from the first two waves of the Continuity and Change in Contraceptive Use (CCCU) study, which gathered information at four points in time from a national sample of women aged 18 39. The online recruitment company GfK administered the survey using their KnowledgePanel, which is composed of approximately 50,000 individuals and is intended to be representative of the U.S. population.

In order to best capture the experiences of women at risk of pregnancy, our baseline survey was restricted to women who had ever had vaginal sex with a man, were not currently pregnant, had not had a tubal ligation and whose main male sex partner had not had a vasectomy. Over a three-week period in November and December of 2012, 11,365 women were invited to participate in the baseline survey. Of those, 6,658 answered the four screening items, yielding a response rate of 59%; 4,647 of those were eligible to participate, and 4,634 completed the full online survey. All 4,647 women were asked to fill out a follow up survey six months later and 3,150, 68%, did so. Expedited approval for the study was obtained from the Guttmacher Institute’s Institutional Review Board.

The current analysis focuses on two pregnancy attitudes. At both surveys, women were asked “How important is it to you to AVOID becoming pregnant now?” and “How would you feel if you found out you were pregnant today?” The items were intended to assess the cognitive and affective dimensions of pregnancy attitudes, respectively. Both items were answered according to a six-point scale, with “1” representing “not at all important” and “very happy” and “6” representing “very important” and “very happy.” The analytic sample (N=2,894) consisted of women who participated in both surveys, answered both pregnancy attitude items at baseline (79 respondents did not answer one or both items), and excludes women who were trying to get pregnant. The latter was based on an item asking: “Which of the following best describes your current plans regarding having another baby?” and refers to the 8% of women who responded “I am trying to get pregnant now.” (Other response categories included “expect to try in the future,” “don’t want to have any (more) children” and “not sure.”)

Consistent contraceptive use was measured using a series of items. All women were asked if they had used any of six prescription methods (pill, patch, ring, shot, the implant or the IUD) in the last 30 days and how consistently they had done so. Women who had had sex with a man in the last 30 days were asked if their partner had used any of five coital or male methods (pulling out/withdrawal, condoms, natural family planning, spermicide or some other barrier method and vasectomy) and how frequently they had done so. I combined information from these items to construct a measure of consistent contraceptive use. Women who reported missing only one pill were considered to be consistent users because clinical studies have shown that these women are not at increased risk of pregnancy [13]. However women missing more than one pill were considered to be inconsistent users as were women who reported use of one or more coital methods in a way that exposed them to the risk of pregnancy (e.g., using condoms and withdrawal, but using each less than half the time, and/or reporting that the methods were used at the same time). More detailed information about the CCCU and the construction of the measure of consistent contraceptive use is available in a previously published study [14].

Among women who were not trying to get pregnant, I first examined each baseline attitudinal item separately and then generated a joint measure. Adapting the approach used in prior research [8], the joint measure classified women as anti-natalist, neutral/indifferent, pro-natalist, positively ambivalent and negatively ambivalent. Among women who were not trying to get pregnant and had had sex with a man in the last 30 days, unadjusted and multivariable logistic regression were used to assess associations between each of the three attitudinal measures and consistent contraceptive use; multivariable models controlled for age, education, number of prior births and race and ethnicity. I next assessed change and consistency in cognitive and affective attitudes at baseline and six months among women who were not trying to get pregnant during either survey period. Finally, I assessed associations between change in each of the two attitudinal measures and changes in consistent contraceptive use, using unadjusted and multivariable logistic regression; these analyses were limited to women who were not trying to get pregnant and had had sex with a man during both survey periods.

Women strongly motivated to avoid pregnancy may be more likely to use IUDs and implants or to adopt sterilization. These methods allow no room for user error, even when attitudes change. I conducted sensitivity analyses by generating multivariable models that excluded respondents using IUDs or implants at either survey (N=316) and those who adopted a permanent contraceptive method during the study period (N=29).

As one-third of the sample was lost to follow up, I compared the distribution of the attitudinal and contraceptive use items among the full samples at baseline and follow up, and among those lost to follow up. The distributions were very similar (e.g., among all three groups 74%–77% were consistent users) suggesting that respondents lost to follow up did not differ according to these outcomes.

3. Results

3.1 Baseline attitudes and associations with contraceptive use

Women reported stronger outlooks about pregnancy avoidance than about pregnancy happiness. A slight majority of respondents, 53%, clearly indicated it was very important to avoid pregnancy (Table 1). At the opposite end of the scale, 7% indicated it was not at all important to avoid pregnancy (even though they were not trying to get pregnant). While not evenly distributed, the extent to which women indicated they would be happy if they got pregnant at the current time was less skewed. Most commonly, 23% indicated they would be not at all happy to be pregnant, and, least commonly, 13% indicated they would be very happy.

Table 1.

Pregnancy avoidance and happiness attitudes at baseline among women not trying to get pregnant

| How important is it to you to avoid becoming pregnant now? | ||

| 1. Not at all important to avoid pregnancy | 192 | 6.6 |

| 2 | 113 | 3.9 |

| 3 | 247 | 8.5 |

| 4 | 368 | 12.7 |

| 5 | 446 | 15.4 |

| 6. Very important to avoid pregnancy | 1,528 | 52.8 |

| How would you feel if you found out you were pregnant today? | ||

| 1. Not at all happy to be pregnant | 670 | 23.2 |

| 2 | 387 | 13.4 |

| 3 | 489 | 16.9 |

| 4 | 600 | 20.7 |

| 5 | 380 | 13.1 |

| 6. Very happy to be pregnant | 368 | 12.7 |

| Total | 2,894 | 100.0 |

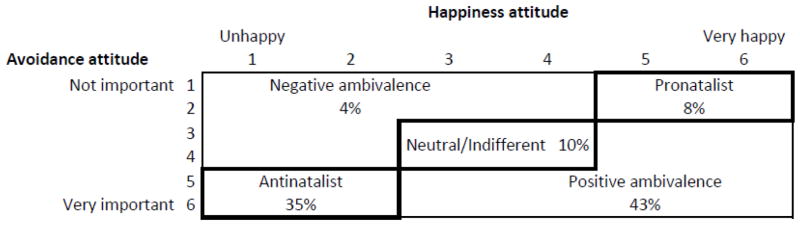

I next examined a measure that took both attitudes into account. Among women who were not trying to get pregnant, 35% were anti-natalist, indicating that it was important to avoid pregnancy and they would be unhappy if a pregnancy occurred (Figure 1). Ten percent of the sample was neutral or indifferent on both items, and an additional 8% were pro-natalist. Altogether, then, slightly more than half of the sample, 53%, was consistent on both attitudes. But the most common set of responses was one of positive ambivalence. Forty-three percent of the sample indicated that they wanted to avoid pregnancy but they would not be unhappy, or would even be happy, if it happened; alternately, they were seemingly neutral about avoiding pregnancy and would be happy if one occurred.

Figure 1.

Joint measure of pregnancy avoidance and happiness attitudes at baseline

Among women who were at risk of unintended pregnancy, 84% used contraception consistently during the last 30 days (Table 2). Of women who indicated it was not at all important to avoid pregnancy, 47% had used contraception consistently compared to 91% among those who indicated it was very important. The disparity in consistent use according to happiness attitude was less pronounced, ranging from 68% among those who would be very happy to 91% among those who would be unhappy. Each measure was independently associated with consistent contraceptive use when examined in separate logistic regression models (Models 1 and 2). However, when both measures were included in the same model (Model 3), only pregnancy avoidance was associated with this outcome; compared to women who expressed a neutral outlook, the odds of being a consistent user were more than two times higher for respondents who indicated it was very important to avoid pregnancy. In the logistic regression models, differences between the strongest and second strongest categories (e.g., 1 vs 2 and 5 vs 6 on the scales) were not significant (not shown), suggesting that it was appropriate to group these together to create a three-category variable.

Table 2.

Percentage using contraception consistently by pregnancy avoidance and happiness attitudes; and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from multivariable logistic regression models assessing consistent contraceptive use; all among women at risk of unintended pregnancy at baseline

| % consistent contraceptive users | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Number | ||||||||||

| Avoidance attitude | ||||||||||

| Not at all important | 128 | 60 (46.9) | 0.25 | 0.16 – 0.38 | -- | -- | 0.27 | 0.18–0.43 | -- | -- |

| 2 | 95 | 58 (61.1) | 0.40 | 0.25–0.64 | -- | -- | 0.42 | 0.26–0.68 | -- | -- |

| 3 (ref) | 203 | 159 (78.3) | 1.00 | -- | -- | 1.00 | -- | -- | ||

| 4 (ref) | 313 | 251 (80.2) | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| 5 | 369 | 324 (87.8) | 1.76 | 1.20–2.58 | -- | -- | 1.64 | 1.11–2.43 | -- | -- |

| Very important | 1,102 | 1000 (90.7) | 2.53 | 1.87–3.42 | -- | -- | 2.20 | 1.54–3.14 | -- | -- |

| Happiness attitude | ||||||||||

| Not at all happy | 437 | 399 (91.3) | -- | -- | 1.73 | 1.16–2.57 | 1.13 | 0.72–1.75 | -- | -- |

| 2 | 287 | 262 (91.3) | -- | -- | 1.68 | 1.07–2.66 | 1.17 | 0.73–1.89 | -- | -- |

| 3 (ref) | 392 | 341 (87.0) | -- | -- | 1.00 | 1.00 | -- | -- | ||

| 4 (ref) | 472 | 397 (84.1) | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| 5 | 325 | 251 (77.2) | -- | -- | 0.59 | 0.43–0.82 | 0.84 | 0.59–1.19 | -- | -- |

| Very happy | 297 | 202 (68.0) | -- | -- | 0.39 | 0.28–0.53 | 0.79 | 0.55–1.14 | -- | -- |

| Joint measure | ||||||||||

| Antinatalist | 699 | 642 (91.9) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 2.70 | 1.76–4.12 |

| Positive ambivalence | 1,024 | 881 (86.0) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.61 | 1.12–2.33 |

| Neutral (ref) | 244 | 195 (79.9) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.00 | |

| Negative ambivalence | 69 | 47 (68.1) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.56 | 0.31–1.02 |

| Pronatalist | 174 | 87 (50.0) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.27 | 0.17–0.42 |

| Total | 2,210 | 1,852 (83.8) | ||||||||

Note: Logistic regression models control for age, eduction, prior births and race/ethnicity

Model 4 included the joint measure. The odds ratio of 2.7 for women with an anti-natalist outlook was slightly higher than the odds ratio of 2.5 for women who indicated it was very important to avoid pregnancy (Model 1), suggesting that the joint measure did not substantially improve the model. Thus, in subsequent analyses examining change over time, I exclude the joint measure.

When users of long-acting methods were excluded all associations were maintained in all four models with one exception: the negative association between negative ambivalence (Model 4) and consistent use became statistically significant (OR .46, 95% CI .25–.88).

3.2 Change over time

The majority of respondents who did not want to become pregnant at either time point were consistent in both attitudes over the six month time period. Most commonly, 61% of respondents indicated it was important to avoid pregnancy on both surveys (Table 3). Twenty-nine percent indicated during both that they would not be happy if they were pregnant, and a slightly smaller proportion, 22% were consistently neutral or indifferent on this measure. Overall, pregnancy avoidance attitudes were significantly more consistent as 75% of respondents reported the same attitude during both time periods compared to 68% who reported the same happiness outlook during both time periods (p<.001, not shown).

Table 3.

Percent distribution of pregnancy avoidance and happiness attitudes at baseline and six months later among women not trying to get pregnant (N=2,658)

| Avoidance attitude | 6 months | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Not important | Neutral | Imporant |

| Not important | 4.6 | 2.3 | 1.7 |

| Neutral/indifferent | 3.8 | 9.4 | 6.7 |

| Important to avoid | 2.5 | 7.9 | 61.0 |

| Happiness attitude | 6 months | ||

| Baseline | Unhappy | Neutral | Happy |

| Unhappy | 28.9 | 8.5 | 1.5 |

| Neutral/indifferent | 7.7 | 22.4 | 8.0 |

| Happy | 1.4 | 4.9 | 16.8 |

| 68.1 | |||

Among women at risk of unintended pregnancy during both surveys, 77% used contraception and used it consistently, 6% did not use contraception or did so inconsistently during both surveys (not shown), and 17% reported a change in consistency. Some 8% of respondents transitioned from inconsistent to consistent contraceptive use between surveys (Table 4); this transition was more common for women who also reported an increase in their desire to avoid pregnancy (13%) and least common for those who expressed a decrease in pregnancy avoidance (5%). (A change in outlook represented a shift in the three-category measure, for example, from “not important to avoid” to “neutral.”) Differences in consistency of contraceptive use according to changes in happiness were smaller. In the multivariable model, reporting a stronger desire to avoid pregnancy at follow up compared to baseline was associated with an increased likelihood of becoming a consistent contraceptive user while changes in happiness about pregnancy were not. (This association was similar in magnitude but became insignificant when users of long-acting methods were excluded, likely due to reduced statistical power; OR 1.63, 95% CI .97–2.72). The same patterns applied to transitioning to inconsistent use, and women who reported that it was less important to avoid pregnancy at follow up were at an increased risk of becoming an inconsistent contraceptive user while happiness was not associated with this outcome.

Table 4.

Percentage who transitioned to consistent and inconsistent contraceptive use by pregnancy avoidance and happiness attitudes; and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from multivariable logistic regression analyses assessing contraceptive use, all among women at risk of unintended pregnancy

| Number | Transitioned to consistent contraceptive use | Transitioned to inconsistent contraceptive use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR | 95% CI | n (%) | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Avoidance attitude | |||||||

| Consistent (ref) | 1,323 | 99 (7.5) | 1.00 | -- | 102 (7.7) | 1.00 | -- |

| More important to avoid | 186 | 24 (12.9) | 1.65 | 1.01–2.68 | 17 (9.1) | 1.38 | 0.79–2.40 |

| Less important to avoid | 269 | 13 (4.8) | 0.65 | 0.35–1.19 | 39 (14.5) | 2.11 | 1.41–3.15 |

| Happiness attitude | |||||||

| Consistent (ref) | 1,214 | 96 (7.9) | 1.00 | -- | 112 (9.2) | 1.00 | -- |

| More happy | 231 | 20 (8.7) | 0.98 | 0.58–1.65 | 16 (6.9) | 0.77 | 0.44–1.33 |

| Less happy | 333 | 20 (6.0) | 0.80 | 0.48–1.33 | 30 (9.0) | 0.91 | 0.59–1.40 |

| Total | 1,778 | 136 (7.6) | 158 (8.9) | ||||

Note: Logistic regression models control for age, race/ethnicity, education and number of prior births

4. Discussion

The current analysis suggests that women’s cognitive pregnancy attitude is more skewed and less variable than their affective pregnancy attitude. More than half of women in the study, 53%, indicated that it is very important to avoid pregnancy, but only 23% would have been “not at all” happy if they found out they were pregnant. Both cognitive and affective attitudes changed over a relatively short period of time for a substantial minority of women, but pregnancy avoidance attitude was more consistent than happiness.

Recently there has been interest in understanding pregnancy ambivalence, defined as holding both positive and negative attitudes towards pregnancy [2,3,4,7,8,9]. However, two findings from this study provide support for the idea that positive feelings about a pregnancy do not contradict a desire to avoid conception; rather feelings and intentions may be distinct concepts for many women [5,10,11,15]. A majority of women reported “consistent” attitudes insofar as their cognitive and affective outlooks corresponded with one another. But the most common outlook, reported by 43% of the sample, was one of positive ambivalence. These respondents typically reported that they wanted to avoid pregnancy, though not strongly, but would not have been unhappy to be pregnant. Rather than view this type of outlook as inconsistent or contradictory, it might be more useful to recognize that cognitive and affective outlooks can be different but compatible. For example, women in unstable financial situations may realize that a baby would bring additional economic hardships but also recognize that it would bring joy to their lives [10]. That only pregnancy avoidance was associated with consistent contraceptive use in most of the models provides further support for the idea that the two outlooks are distinct [5,10,11], and that cognitive attitude plays a more important role when it comes to pregnancy prevention. While women may recognize that they would be happy if they found out they were pregnant, many will pursue strategies to prevent a pregnancy they want to avoid [12]. This study has several shortcomings. The baseline sample was not nationally representative, and was older, more educated and more likely to be married relative to the larger population of comparable women [17]. One-third of the original sample did not participate in the follow up survey, potentially exacerbating this shortcoming. Still, the findings are based on data from more than 1,700 respondents, and it is likely that many of the patterns and associations are applicable to a sizeable subpopulation of U.S. women. Attitudinal measures, which were the focus of this study, are necessarily subjective and imprecise, and we must be careful not to make too much of differences in scales that may be interpreted differently by different women, or by the same women at different points in time. Finally, this study did not account for male partners’ cognitive or affective pregnancy attitudes, and these are likely to influence women’s attitudes [16] and contraceptive use patterns [11,17].

In conclusion, it is important to recognize that a substantial minority of women who want to avoid pregnancy would nonetheless be happy if they found out they were pregnant. Individuals who work in the field of reproductive health should be careful not to “problematize” this outlook. This study suggests that pregnancy avoidance attitudes plays the more important role when it comes to contraceptive use, and health care providers should be sure to assess this outlook when discussing contraception with patients.

Acknowledgments

I thank my colleague Laura Lindberg for assistance in developing the project and for providing feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Funding: Data analyses and summary of the findings were supported by a grant from the Society of Family Planning. Additional support was provided by the Guttmacher Center for Population Research Innovation and Dissemination (NIH grant 5 R24 HD074034).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Miller WB. Why some women fail to use their contraceptive method: a psychological investigation. Fam Plan Perspect. 1986;18(1):27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwarz EB, Lohr PA, Gold MA, Gerbert B. Prevalence and correlates of ambivalence towards pregnancy among nonpregnant women. Contraception. 2007;75(4):305–10. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frost JJ, Singh S, Finer LB. Factors associated with contraceptive use and nonuse, United States, 2004. Perspect Sex Repro Health. 2007;39(2):90–9. doi: 10.1363/3909007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kavanaugh ML, Schwarz EB. Prospective assessment of pregnancy intentions using a single- versus a multi-item measure. Perspect Sex Repro Health. 2009;41(4):238–43. doi: 10.1363/4123809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachrach CA, Newcomer S. Intended pregnancies and unintended pregnancies: distinct categories or opposite ends of a continuum? Fam Plan Perspect. 1999;31(5):252–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins JA, Hirsch JS, Trussell J. Pleasure, prophylaxis and procreation: a qualitative analysis of intermittent contraceptive use and unintended pregnancy. Perspect Sex Repro Health. 2008;40(3):130–7. doi: 10.1363/4013008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreau C, Hall K, Trussell J, Barber JS. Effect of prospectively measured pregnancy intentions on the consistency of contraceptive use among young women in Michigan. Hum Repro. 2013;28(3):642–50. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoo SH, Guzzo KB, Hayford SR. Understanding the complexity of ambivalence toward pregnancy: Does it predict inconsistent use of contraception? Biodemography Social Bio. 2014;60(1):49–66. doi: 10.1080/19485565.2014.905193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JA, Popkin RA, Santelli JS. Pregnancy ambivalence and contraceptive use among young adults in the United States. Perspect Sex Repro Health. 2012;44(4):236–43. doi: 10.1363/4423612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aiken ARA, Dillaway C, Mevs-Korff N. A blessing I can’t afford: Factors underlying the paradox of happiness about unintended pregnancy. Social Science Med. 2015;132:149–55. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aiken ARA, Potter JE. Are Latina women ambivalent about pregnancies they are trying to prevent?. Evidence from the border contraceptive access study. Perspect Sex Repro Health. 2016;45(4):196–203. doi: 10.1363/4519613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aiken ARA. Happiness about unintended pregnancy and its relationship to contraceptive desires among a predominantly Latina cohort. Perspect Sex Repro Health. 2015;47(2):99–106. doi: 10.1363/47e2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zapata LB, Steenland MW, Brahmi D, Marchbanks PA, Curtis KM. Effect of missed combined hormonal contraceptives on contraceptive effectiveness: a systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87(5):685–700. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones RK, Tapales A, Lindberg LD, Frost J. Using longitudinal data to understand changes in consistent contraceptive use. Perspect Sex Repro Health. 2015;47(3):131–9. doi: 10.1363/47e4615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aiken ARA, Borrero S, Callegari L, Dehlendorf C. Rethinking the pregnancy planning paradigm: Unintended conceptions or unrespresentative concepts? Perspect Sex Repro Health. 2016;48(3) doi: 10.1363/48e10316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones RK. Are uncertain fertilty intentions a temporary or long-term outlook? Findings from a panel study. Women Health. 2016;16:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kraft JM, Harvey SM, Hatfield-Timajchy K, Beckman L, Farr SL, Jamieson DJ, et al. Pregnancy motivations and contraceptive use: hers, his, or theirs? Women Health. 2010;20(4):234–41. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]