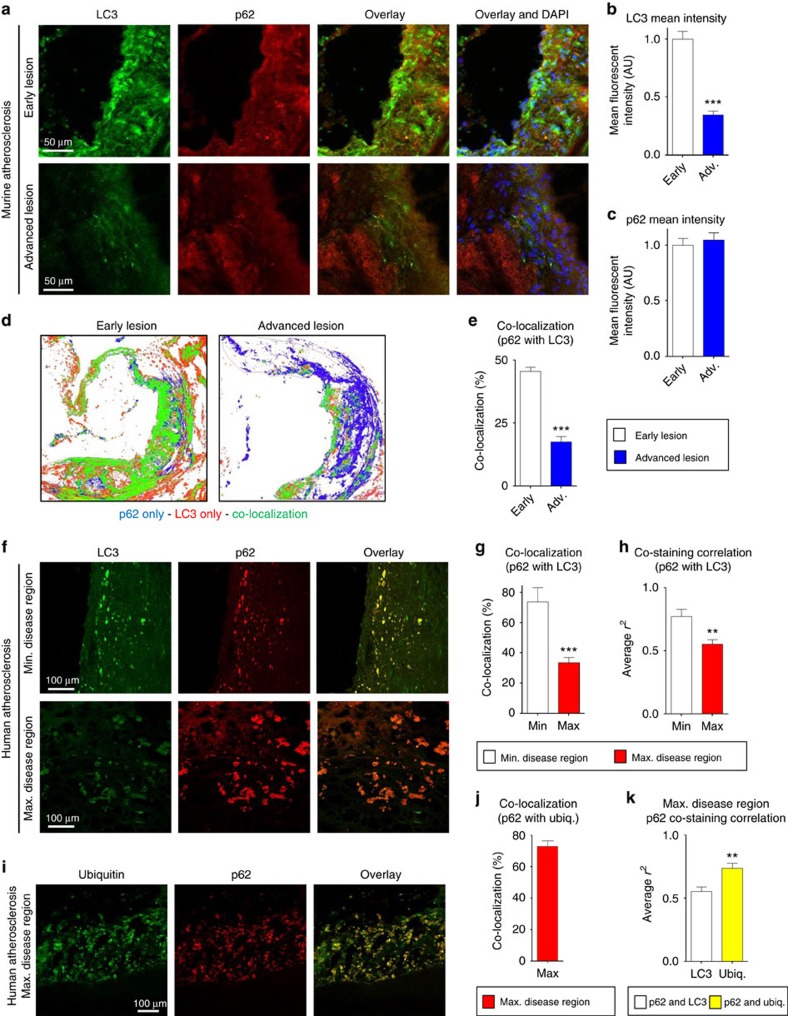

Figure 1. Mouse and human atherosclerotic plaques develop features of a progressive autophagy dysfunction.

(a–c) Representative immunofluorescence images of early-stage and more advanced atherosclerotic (ApoE-KO) aortic roots co-stained with antibodies against LC3 and p62. Early and advanced lesions were obtained from ApoE-KO mice fed a western diet for <2 months and 3–4 months, respectively (scale bar, 50 μm (a)). The mean intensity for LC3 and p62 stainings were analysed (n=5 mice for each group; b,c). (d,e) Co-localization of LC3 and p62 was also analysed in the same aortic roots. Representative co-localization images are shown from early and more advanced lesions (green indicates LC3/p62 co-localized, red indicates LC3-positive, and blue indicates p62-positive areas) (d). LC3/p62 co-localization is quantified as per cent of total signal (e). (f–k) Immunofluorescence analysis of human carotid endarterectomy specimens (n=8), which are separated as maximally- and adjacent minimally diseased regions (scale bar, 100 μm). Specimens were co-stained with LC3 and p62 (f), and co-localization (g) as well as correlation of staining intensity (h) between maximally and minimally diseased regions are quantified. Maximally diseased human atherosclerotic regions were co-stained for p62 and polyubiquitinated proteins (FK-1 antibody; i), and co-localization quantified (j). (k) Graph represents a comparison of the staining correlation between p62/LC3 versus p62/ubiquitin(FK-1) in maximally atherosclerotic regions. For all graphs, data are presented as mean±s.e.m. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, two-tailed unpaired t-test. Max, maximum; Min, minimum; Ubiq., ubiquitination.