Abstract

Objective

The genus Roseomonas comprises a group of pink-pigmented, slow-growing, aerobic, non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria, which have been isolated from environmental sources such as water and soil, but are also associated with human infections. In the study presented here, Roseomonas mucosa was identified for the first time as part of the endodontic microbiota of an infected root canal and characterised in respect to growth, antibiotic susceptibility and biofilm formation.

Results

The isolated R. mucosa strain showed strong slime formation and was resistant to most β-lactam antibiotics, while it was susceptible to aminoglycosides, carbapenemes, fluorochinolones, polymyxines, sulfonamides and tetracyclines. Biofilm formation on artificial surfaces (glass, polystyrene, gutta-percha) and on teeth was tested using colorimetric and fluorescence microscopic assays. While solid biofilms were formed on glass surfaces, on the hydrophobic surface of gutta-percha points, no confluent but localised, spotty biofilms were observed. Furthermore, R. mucosa was able form biofilms on dentin. The data obtained indicate that R. mucosa can support establishment of endodontic biofilms and furthermore, infected root canals might serve as an entrance pathway for blood stream infections by this emerging pathogen.

Keywords: Antibiotic susceptibility, Biofilm formation, Emerging pathogen, Endodontic infections, Root canal colonization, Systemic infections

Background

Biofilms are groups of sessile microorganisms living within a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substances. These microbial communities are ubiquitously found on abiotic and biotic surfaces including human implants and tissues. In bacterial infections, biofilm formation can significantly increase pathogenicity of bacteria and protection of microorganisms from disinfectants and antibiotics (for a recent overview, see [1]). Mixed biofilm communities are also involved in dental infections, e.g. infections of the root canal [2]. The often complex anatomies of root canals with e.g. isthmuses and lateral canals [3, 4] can cause failure of endodontic therapy due to the persistence of microorganisms in the root canal system and dentin tubules due to insufficient removal of biofilm and disinfection [5]. Beside some prominent species, such as Enterococcus faecalis (see e.g. [6]), which are observed routinely, different Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria as well as yeasts have already been described as part of the microbiota of infected root canals (see e.g. [7–9]). Many of these microorganisms are only poorly characterised, although they might significantly contribute to persistence of the microbiota. Special properties which might be important in this respect are e.g. the production of antibiotic resistance determinants or extracellular polymer matrices crucial for biofilm formation [10].

In this communication, we describe the characterization of a Roseomonas mucosa strain isolated during treatment of an infected root canal. The genus Roseomonas comprises a group of pink-pigmented, slow-growing, aerobic, non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria, which have been isolated from environmental sources such as water and soil, but are also associated with human infections [11–15]. Twenty different species with validly published names were described [16, 17]. Infections of humans with Roseomonas species are rare and mainly observed in immunocompromised patients, most likely due to a low pathogenic potential of the bacteria. Catheter-related bloodstream, urinary and respiratory tract infections with different species of the genus were reported [18, 19]. R. mucosa seems to be the most prevalent species in clinical samples [18, 20, 21] and skin microbiota seems to be the main reservoir of this species [22]. In contrast to other species, in case of infections with R. mucosa, a considerable number of immunocompetent patients have been reported [20, 23] indicating a higher pathogenicity and making the bacterium an emerging pathogen [22].

Methods

Sample collection

Samples were collected during regular root canal treatment following informed patient consent and ethics commission approval. Following local anesthesia and isolation of the tooth with rubber dam (Roeko Flexi Dam non latex, Coltene/Whaledent, Langenau, Germany), access cavities to the pulp chambers of the teeth were created using high speed diamond rotary instruments under ambient irrigation. The root canals were subsequently instrumented using sterile C-Pilot files (ISO size 08, 10, 15, VDW, Munich, Germany) which were directly placed in sterile 2 ml test tubes. 2 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline was added and the samples were vortexed for 60 s. Subsequently, the buffer was plated-out on different nutrient agar plates (BHI, Columbia Blood Agar, LB, Slanetz and Bartley) obtained from Oxoid (Basingstoke, UK). Arising colonies were streaked-out at least twice to obtain pure cultures, which were used for identification. In summary, pilot files from 13 root canal-treated teeth were investigated, with six showing no bacterial colonization.

Mass spectrometric identification

A thin layer of bacteria from fresh colonies was spotted on a stainless steel target using a toothpick and overlaid with 1 µl of HCCA matrix (10 mgl α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid ml−1 in 50% acetonitrile/2.5% trifluoro-acetic acid). After drying at ambient temperature identification was performed by MALDI-TOF MS using a Microflex LTTM and the BiotyperTM 3.1 Software (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany) on the basis of 240 single spectra.

Antibiotic susceptibility test

Susceptibility to antibiotics was tested by incubation of bacteria and together with antibiotic disks for 48 h on Mueller–Hinton agar and results were interpreted using the breakpoints for zone diameters of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST, http://www.eucast.org). When no breakpoints were available, criteria for related bacteria have been used.

Biofilm formation

Biofilm formation on artificial surfaces was tested in glass tubes filled with 4 ml BHI and LB medium, respectively. Tubes were incubated on a rotary shaker at 37 °C and biofilm formation was analysed after 1, 3 and 5 days. For this purpose, medium (control) and R. mucosa cultures were removed, the tubes were washed twice with water and biofilm staining and quantitative analysis was carried out as described [24]. For colonization of gutta-percha points (Maxima gutta-percha points #30, Henry Schein Dental, Langen, Germany) these were incubated with bacteria in glass tubes (control: incubation in not inoculated medium). Additionally, biofilm formation on polystyrene was tested in microtiter plates [24].

Fluorescence microscopy of dentin colonization

For fluorescence microscopy, extracted bisected and sterilized teeth were incubated in R. mucosa-inoculated BHI medium flasks for 3–4 days. For staining, teeth sections were removed from the flasks, rinsed with distilled water and incubated for 15 min in SYTO9 solution (ThermoFisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany). Fluorescence microscopic inspection at 20× magnification was carried out using a Zeiss Axio Imager A1 (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany) with fixed wavelength and filters for GFP fluorescence equipped with a digital camera (Zeiss Axio Cam MRc5) and analysing software (Zeiss ZEN 2011, version 1.0).

Results

Isolation of microorganisms and growth of Roseomonas mucosa

In frame of this study, thirteen teeth were tested for microbial colonization of the root canal. In seven cases, microorganisms could be isolated (see Table 1), while six samples were sterile. The majority of isolates were identified as infectors of the human root canal before, e.g. bacteria such as Actinomyces oris, E. faecalis, Lactobacillus species, Streptococcus oralis and Streptococcus sanguinis or yeasts such as Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis,. Among microorganisms isolated from a file used to prepare the root canals of an inflamed tooth, pinkish white pigmented colonies with a mucoid, almost runny appearance were frequently observed. Pure cultures were obtained by careful re-streaking (Fig. 1) and using MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry the corresponding bacteria were identified as R. mucosa with a score of 2.4. The bacteria grew on all tested media (Columbia Blood Agar, LB, Slanetz and Bartley), with a preference on rich BHI medium. Slime formation was observed on all solid media tested as well as in liquid culture from which the extracellular polymer could be easily harvested by filtration (data not shown).

Table 1.

Microbial species isolated from infected root canals

| Phylum | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

| Actinobacteria | Actinomyces | naeslundii |

| Actinomyces | oris | |

| Rothia | aeria | |

| Rothia | dentocariosa | |

| Corynebacterium | durum | |

| Firmicutes | Bacillus | pumilus |

| Enterococcus | faecalis | |

| Enterococcus | faecium | |

| Lactobacillus | casei | |

| Lactobacillus | paracasei spp. paracasei | |

| Lactobacillus | plantarum | |

| Lactobacillus | Rhamnosus | |

| Staphylococcus | Hominis | |

| Streptococcus | Oralis | |

| Streptococcus | Sanguinis | |

| Proteobacteria | Roseomonas | Mucosa |

| Ascomycota | Candida | Albicans |

| Candida | Dubliniensis |

Fig. 1.

Colonies of R. mucosa. Bacteria were streaked-out on LB agar plates and incubated at 37 °C. A strong formation of slime is observed giving the streak-out a runny appearance

Antibiotics resistance

When the isolated strain was tested in respect to antibiotics resistance using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion test, R. mucosa showed resistance to the β-lactam antibiotics ampicillin, ampicillin/sulbactam, piperacillin and piperacillin/tazobactam as well to the cephalosporines cefazolin, cefuroxime and ceftazidime. Surprisingly and in contrast to the other cephalosporines and penicillines tested, R. mucosa was susceptible to ceftriaxone. Sensitivity to the carbapenemes imipenem and meropenem, to the aminoglycosides gentamicin, tobramicin and amikacin and to the fluorochinolone ciprofloxacin was observed, while the strain was resistant to fosfomycin. Sensitivity was also found to the sulfonamides trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, the tetracycline antibiotics tetracycline and tigecycline and to polymyxin B (Table 2).

Table 2.

Susceptibility of R. mucosa to antibiotics

| Antibiotic | Amount (µg) | Breakpoint (mm) | Susceptibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Lactams (penicillins and cephalosporins) | |||

| Ampicillin | 10 | 6 | Resistant |

| Ampicillin/sulbactam | 10/10 | 6 | Resistant |

| Piperacillin | 100 | 6 | Resistant |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 100/10 | 6 | Resistant |

| Cefazolin | 30 | 6 | Resistant |

| Cefuroxime | 30 | 6 | Resistant |

| Ceftriaxone | 30 | 40 | Sensitive |

| Ceftazidime | 10 | 6 | Resistant |

| Carbapenemes | |||

| Imipenem | 10 | 43 | Sensitive |

| Meropenem | 10 | 38 | Sensitive |

| Aminoglycosides | |||

| Gentamicin | 10 | 40 | Sensitive |

| Tobramicin | 10 | 42 | Sensitive |

| Amikacin | 30 | 48 | Sensitive |

| Fluorochinolones | |||

| Ciprofloxacin | 5 | 35 | Sensitive |

| Fosfomycin | 200 | 6 | Resistant |

| Sulfonamide | |||

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 1.25/23.75 | 22 | Sensitive |

| Tetracyclines | |||

| Tetracycline | 30 | 34 | Sensitive |

| Tigecycline | 15 | 37 | Sensitive |

| Polymyxines | |||

| Polymyxin B | 300 E | 20 | Sensitive |

Susceptibility to antibiotics was tested by incubation of bacteria together with antibiotic disks for 48 h on Mueller–Hinton agar and results were interpreted using the breakpoints for zone diameters of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST, http://www.eucast.org)

Biofilm formation

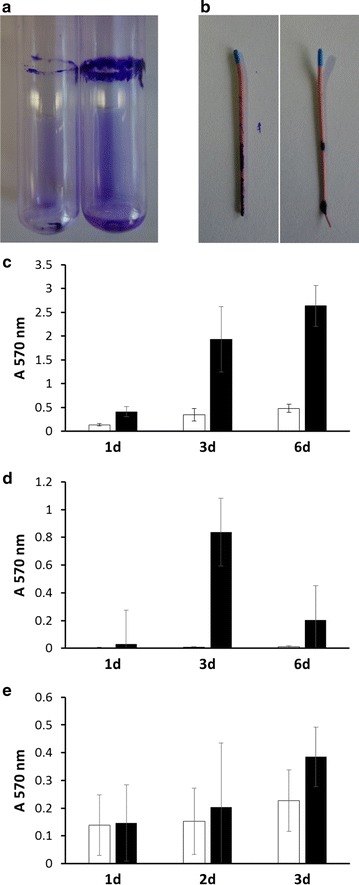

The extremely slimy, almost runny appearance of R. mucosa colonies (Fig. 1) indicated a strong formation of extracellular polymers, which may protect the bacteria against dehydration and detrimental environmental conditions. Furthermore, the polymer might support biofilm formation. Different surfaces were tested, starting with established model material such as glass and polystyrene [24] followed by gutta-percha points used as filling material in root canal treatment as well as teeth, and extracellular polymers and sessile bacteria were stained using crystal violet. Independent of the medium and surface material used, biofilm formation was detectable (Fig. 2). R. mucosa grew predominantly at the medium-air interphase (Fig. 2a), as it can be expected due to a higher energy yield when oxygen is used as final electron acceptor. A time course of biofilm formation on glass (test tube), gutta-percha and polystyrene (microtiter plate) surfaces and in LB and BHI medium revealed that biofilm formation is coupled to growth of the culture and increases with time.

Fig. 2.

Biofilm formation on artificial surfaces. a Image of a crystal violet-stained biofilm of R. mucosa on the glass surface of a test tube after 6 days of growth. Note the strong stain at the medium-air interphase. b Colonization of gutta-percha points. Quantitative analysis of biofilm formation on glass (c), gutta-percha (d) and polystyrene (e) during growth in LB (white columns) and BHI (black columns) medium. Experiments were carried out at least in three biological replicates and standard deviations are shown

While glass surfaces were colonized best and stable, solid biofilms were formed (Fig. 2a, c), gutta-percha points and polystyrene surfaces did support only weak attachment of the bacteria. On the surface of gutta-percha points, which comprise a hydrophobic surface, no confluent but local, spotty biofilms were observed (Fig. 2b), which showed high variability and low stability. After 6 days of incubation, previously formed biofilms fell off the gutta-percha points (Fig. 2d). Also biofilms on polystyrene were characterised by only loosely attached material resulting in high standard deviations in quantitative biofilm analyses (Fig. 2e).

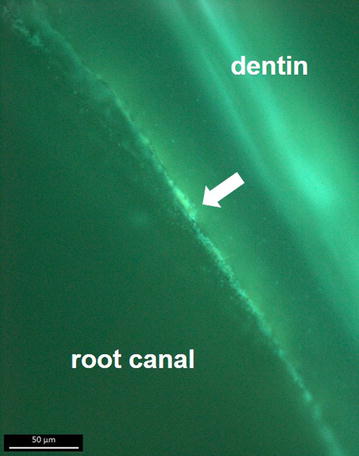

Biofilm formation on dentin, the natural surface of the root canal, was tested using extracted teeth. Bacteria were stained with SYTO9, a fluorescent dye penetrating the cell membrane, and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. As shown in Fig. 3, bacteria were colonizing the wall of the root canal in a compact layer of cells and extracellular material.

Fig. 3.

Colonization of dentin. Bisected teeth were incubated for 7 days at 37 °C with R. mucosa. Immediately before fluorescence microscopy, teeth were incubated for 15 min with green-fluorescent dye SYTO9. After removal of the fluorescent dye and a washing step with distilled water, bacteria were visualized using a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 microscope. Bacteria, which appear as light green spots embedded in biofilm matrix mainly in the middle of the image (indicated by an arrow), are predominantly found at the root canal surface, while the dentin shows an even green auto-fluorescence. Scale bar 50 µm

Discussion

Roseomonas mucosa seems to be the most prevalent Roseomonas species in clinical samples and in contrast to other Roseomonas species, a considerable number infections of immunocompetent patients has been reported [20, 23]. While previously infections were attributed to environmental sources, a recent study suggest skin microbiota being the main reservoir of this emerging pathogen [22]. The isolation of R. mucosa from an infected root canal in this study hint to the possibility that besides catheters also infected teeth might be an entrance pathway for blood stream infections by this pathogen. As indicated by its name, R. mucosa is characterised by a strong slime formation, which might be beneficial for biofilm formation. In fact, attachment of the bacteria to different abiotic and biotic surfaces including dentin was found and biofilm material could also be harvested from liquid cultures (data not shown). Hydrophobic surfaces like gutta-percha points seem to obstruct sessile growth of R. mucosa.

Biofilms on the root canal wall as found in this study are involved in primary apical periodontitis and may support colonisation of dentinal tubules, which might subsequently contributes to resistance to treatment with disinfectants [2, 5] and antibiotics. R. mucosa was susceptible to ceftriaxone, whereas all other cephalosporines and penicillines turned out completely resistant. These results are in accordance with observations made in a recent study by Romano-Bertrand and co-workers ([22]. These authors suggested the production of β-lactamase as reason for resistance. Consequently, the observed resistance to these antibiotics might also protect other pathogenic bacteria from antibiotic treatment when growing together with R. mucosa in multispecies biofilms in the host.

Limitations

This first report of the isolation of R. mucosa from an infected root canal and the characterisation of biofilm formation of the corresponding strain might further contribute to the knowledge on this emerging pathogen and its reservoirs. However, further studies besides this single case report and initial experiments are necessary to establish that R. mucosa is a significant member of the microbiota of infected root canals and to fully understand its role in oral health.

Authors’ contributions

ND carried out growth experiments and characterized biofilm formation, SK isolated the strain from files of a root canal treatment, WG identified the isolate and carried out antibiotic susceptibility testing, TG-K was responsible for fluorescence microscopy, MK and AB designed the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The support of A.B. by the Dr. Hertha und Helmut Schmauser-Stiftung is gratefully acknowledged.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Strain and data will be provided by the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical approval

Isolation of microorganisms from C-pilot files was carried out following informed patient consent and ethics commission approval (Ethics committee Approval 159_16B, Medical Faculty, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg). All participants gave their informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nina Diesendorf, Email: nina.diesendorf@web.de.

Stefanie Köhler, Email: stefanie.koehler89@gmx.net.

Walter Geißdörfer, Email: Walter.Geissdoerfer@uk-erlangen.de.

Tanja Grobecker-Karl, Email: Tanja.Grobecker-Karl@uk-erlangen.de.

Matthias Karl, Email: matthias.karl@uks.eu.

Andreas Burkovski, Phone: +49 9131 85 28086, Email: andreas.burkovski@fau.de.

References

- 1.Gupta P, Sarkar S, Das B, Bhattacharjee S, Tribedi P. Biofilm, pathogenesis and prevention–a journey to break the wall: a review. Arch Microbiol. 2016;198:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00203-015-1148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Y, Shen Y, Wang Z, Huang X, Maezono H, Ma J, Cao Y, Haapasalo M. Evaluation of the susceptibility of multispecies biofilms in dentinal tubules to disinfecting solutions. J Endod. 2016;42:1246–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paque F, Ganahl D, Peters OA. Effects of root canal preparation on apical geometry assessed by micro-computed tomography. J Endod. 2009;35:1056–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricucci D, Siqueira JF., Jr Fate of the tissue in lateral canals and apical ramifications in response to pathologic conditions and treatment procedures. J Endod. 2010;36:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ordinola-Zapata R, Bramante CM, Garcia RB, de Andrade FB, Bernardineli N, de Moraes IG, Duarte MA. The antimicrobial effect of new and conventional endodontic irrigants on intra-orally infected dentin. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013;71:424–431. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2012.690531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George S, Kishen A, Song KP. The role of environmental changes on monospecies biofilm formation on root canal wall by Enterococcus faecalis. J Endod. 2005;31:867–872. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000164855.98346.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins MD, Hoyles L, Kalfas S, Sundquist G, Monsen T, Nikolaitchouk N, Falsen E. Characterization of Actinomyces isolates from infected root canals of teeth: description of Actinomyces radicidentis sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3399–3403. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.9.3399-3403.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murad CF, Sassone LM, Faveri M, Hirata R, Jr, Figueiredo L, Feres M. Microbial diversity in persistent root canal infections investigated by checkerboard DNA-DNA hybridization. J Endod. 2014;40:899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henriques LC, de Brito LC, Tavares WL, Teles RP, Vieira LQ, Teles FR, Sobrinho AP. Microbial ecosystem analysis in root canal infections refractory to endodontic treatment. J Endod. 2016;42:1239–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nair PN. On the causes of persistent apical periodontitis: a review. Int Endod J. 2006;39:249–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace PL, Hollis DG, Weaver RE, Moss CW. Biochemical and chemical characterization of pink-pigmented oxidative bacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:689–693. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.4.689-693.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rihs JD, Brenner DJ, Weaver RE, Steigerwalt AG, Hollis DG, Yu VL. Roseomonas, a new genus associated with bacteremia and other human infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3275–3283. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.12.3275-3283.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han XY, Pham AS, Tarrand JJ, Rolston KV, Helsel LO, Levett PN. Bacteriologic characterization of 36 strains of Roseomonas species and proposal of Roseomonas mucosa sp nov and Roseomonas gilardii subsp rosea subsp nov. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:256–264. doi: 10.1309/731VVGVCKK351Y4J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elshibly S, Xu J, McClurg RB, Rooney PJ, Millar BC, Alexander HD, Kettle P, Moore JE. Central line-related bacteremia due to Roseomonas mucosa in a patient with diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:611–614. doi: 10.1080/10428190400029908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sipsas NV, Papaparaskevas J, Stefanou I, Kalatzis K, Vlachoyiannopoulos P, Avlamis A. Septic arthritis due to Roseomonas mucosa in a rheumatoid arthritis patient receiving infliximab therapy. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;55:343–345. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung EJ, Yoon HS, Kim KH, Jeon CO, Chung YR. Roseomonas oryzicola sp. nov., isolated from the rhizosphere of rice (Oryza sativa L.) Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65:4839–4844. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JH, Kim MS, Baik KS, Kim HM, Lee KH, Seong CN. Roseomonas wooponensis sp. nov., isolated from wetland freshwater. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65:4049–4054. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De I, Rolston KV, Han XY. Clinical significance of Roseomonas species isolated from catheter and blood samples: analysis of 36 cases in patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1579–1584. doi: 10.1086/420824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bard JD, Deville JG, Summanen PH, Lewinski MA. Roseomonas mucosa isolated from bloodstream of pediatric patient. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3027–3029. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02349-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang CM, Lai CC, Tan CK, Huang YC, Chung KP, Lee MR, Hwang KP, Hsueh PR. Clinical characteristics of infections caused by Roseomonas species and antimicrobial susceptibilities of the isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;72:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim YK, Moon JS, Song KE, Lee WK. Two cases of bacteremia due to Roseomonas mucosa. Ann Lab Med. 2016;36:367–370. doi: 10.3343/alm.2016.36.4.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romano-Bertrand S, Bourdier A, Aujoulat F, Michon AL, Masnou A, Parer S, Marchandin H, Jumas-Bilak E. Skin microbiota is the main reservoir of Roseomonas mucosa, an emerging opportunistic pathogen so far assumed to be environmental. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(737):e731–e737. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim KY, Hur J, Jo W, Hong J, Cho OH, Kang DH, Kim S, Bae IG. Infectious spondylitis with bacteremia caused by Roseomonas mucosa in an immunocompetent patient. Infect Chemother. 2015;47:194–196. doi: 10.3947/ic.2015.47.3.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Toole GA, Kolter R. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:449–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Strain and data will be provided by the corresponding author on reasonable request.