Abstract

Context

We report a case of syringomyelia assessed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with a time-spatial labeling inversion pulse (Time-SLIP), which is a non-contrast MRI technique that uses the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) as an intrinsic tracer, thus removing the need to administer a contrast agent. Time-SLIP permits investigation of flow movement for over 3 seconds without any limitations associated with the cardiac phase, and it is a clinically accessible method for flow analysis.

Findings

We investigated an 85-year-old male experiencing progressive gait disturbance, with leg numbness and muscle weakness. Conventional MRI revealed syringomyelia from C7 to T12, with multiple webs of cavities. We then applied the Time-SLIP approach to characterize CSF flow in the syringomyelic cavities. Time-SLIP detected several unique CSF flow patterns that could not be observed by conventional imaging. The basic CSF flow pattern in the subarachnoid space was pulsatile and was harmonious with the heartbeat. Several unique flow patterns, such as bubbles, jumping, and fast flow, were observed within syringomyelic cavities by Time-SLIP imaging. These patterns likely reflect the complex flow paths through the septum and/or webs of cavities.

Conclusion/Clinical Relevance

Time-SLIP permits observation of CSF motion over a long period of time and detects patterns of flow velocity and direction. Thus, this novel approach to CSF flow analysis can be used to gain a more extensive understanding of spinal disease pathology and to optimize surgical access in the treatment of spinal lesions. Additionally, Time-SLIP has broad applicability in the field of spinal research.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Time-spatial labeling inversion pulse (Time-SLIP), Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), Syringomyelia, Spinal disease

Introduction

We report a case of syringomyelia assessed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), using a time-spatial labeling inversion pulse (Time-SLIP) method. This technique enables noninvasive visualization of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) dynamics, which offers several advantages over conventional MRI.1 We describe a spectrum of unique findings obtained using this new approach and demonstrate its feasibility for analyzing spinal disease.

Materials and methods

Case description

An 85-year-old old male patient with crutch gait visited our hospital with a complaint of progressive gait disturbance over the previous few months. A neurological survey revealed leg numbness and muscle weakness (Manual Muscle Testing [MMT] score = 3–4).

Radiographic assessment showed typical degenerative changes. Routine MRI revealed syringomyelia, localized from C7 to T12, with a well-defined horn and long tail. T1-weighted images showed multiple syrinx cavities with a web-like pattern (Fig. 1). We further investigated the CSF flow properties using the Time-SLIP MRI approach.

Figure 1.

An 85-year old man with syringomyelia. Routine MRI revealed a cavity localized from C7 to T12 that had a gradually enlarged horn and a long thoracic tail. T1-weighted imaging detected syrinxes forming multiple webs and T2-weighted imaging showed syringomyelic cysts within the spinal cord.

Principles of Time-SLIP

Time-SLIP is a non-contrast MRI technique that uses the CSF itself as an intrinsic visual tracer through an inversion recovery (IR) pulse that enables the tagged CSF to generate image contrast.1 Image data acquisition over different intervals of applied IR pulses (i.e. inversion times [TI]) in the same region permits visualization of CSF flow dynamics. Time-SLIP was performed using a 1.5-T MRI system.

Results

Time-SLIP revealed a complex CSF flow that included stagnant and irregular fluid motion, without any limitations in flow velocity or direction. The basic CSF flow pattern in the subarachnoid space was brisk and pulsatile (Fig. 2). At the upper cervical spine, Time-SLIP demonstrated pulsatile motion in the cranio-caudal direction. The overall net flow over the imaging series was in the caudal direction. Thus, we estimated that the cumulative flow motion was downstream of this point.

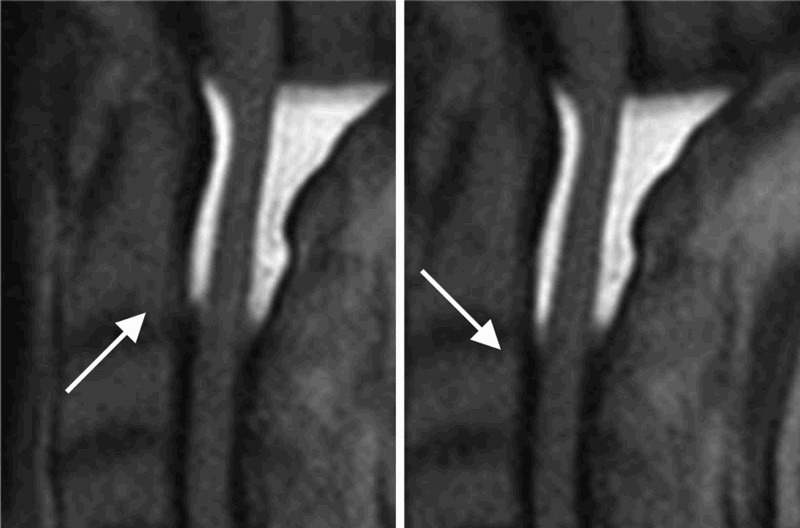

Figure 2.

Time-SLIP MRI images at C0–2. Time-SLIP revealed both intra- and peri-spinal cord CSF flow dynamics. The flow complex at the upper cervical level showed a basic flow pattern of pulsatile flow motion in the cranio-caudal direction, which was dominant in the ventral space compared to the dorsal space (arrow).

Time-SLIP analysis allowed us to decipher both the intra- and peri-spinal cord CSF flow dynamics. Furthermore, specific flow patterns unique to syringomyelia were observed in the intramedullary space. At the head of the syrinx, we found that inflow was synchronized with the flow in the ventral subarachnoid space and observed a direct connection to the central canal. The net flow gradually moved in the downward direction over the time course of imaging (Fig. 3).

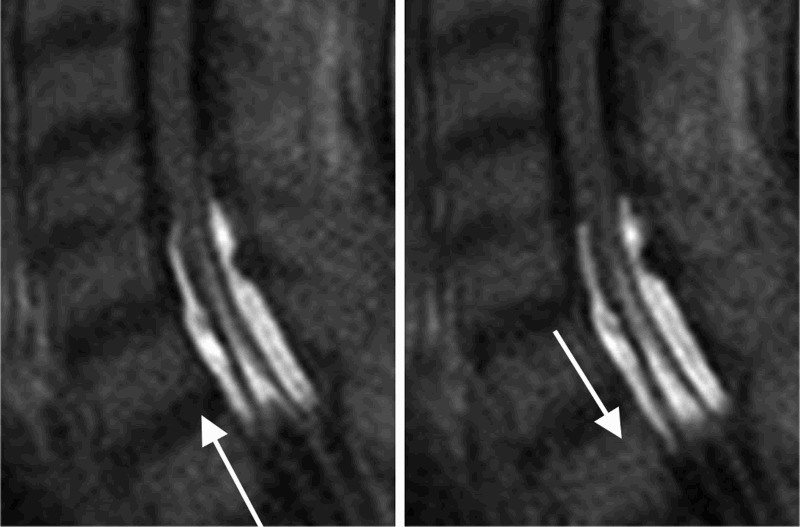

Figure 3.

Time-SLIP images of the head of syringomyelia (C6/7). Time-SLIP revealed CSF inflow through the central canal of the spinal cord, moving slowly with pulsatile motion in the caudal direction. The direct interaction between the aqueduct and syringomyelic cavity may contribute to the pathologic mechanism of syrinx formation.

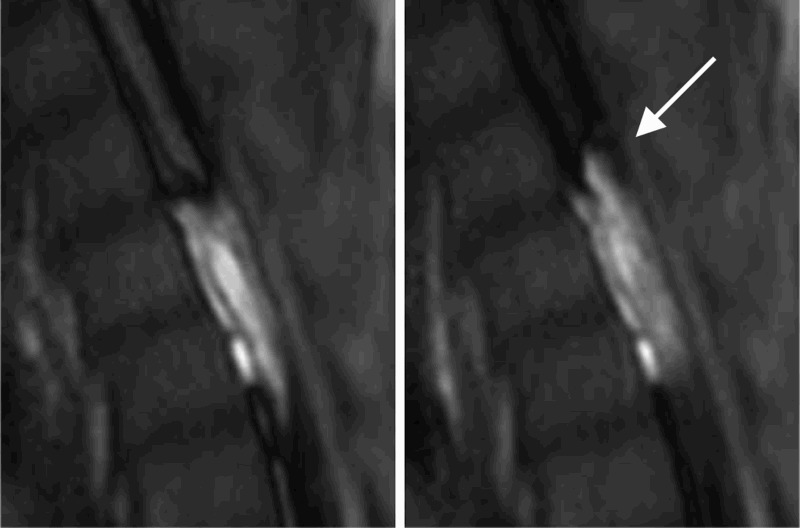

We observed three types of intra-syrinx flow: fast, bubble, and jumping flow. The fast flow may have resulted from a narrow path or slight obstruction. The appearance of bubbles may indicate turbulent flow. Jumping flow across the web and septum of the syrinx indicated continuous flow between these cavities (Fig. 4). Fluent flow may be preferable for resolving syringomyelic cavities. However, bubbling and jumping flow results in more obstructive cavities, with webs.

Figure 4.

Time-SLIP image at T4. This figure reveals direct interactions between compartments in syringomyelia resulting from direct connections and flow throughout the web-like cavities.

Discussion

This is the first report of a new approach involving MRI assessment using Time-SLIP for non-invasively evaluating CSF flow in patients with spinal disease. This approach enabled the instantaneous visualization of CSF motion. Furthermore, Time-SLIP also detected CSF motion over a period of 3 seconds, without any limitations. Consequently, Time-SLIP allowed meticulous assessment of CSF motion within the syringomyelia cavity, which may improve our understanding of disease pathology.

Several MRI techniques have been developed for quantitative and qualitative flow analysis. The Time-SLIP technique can be used to evaluate blood flow dynamics and pancreatic secretions.2–10 Moreover, Time-SLIP has been used to evaluate CSF motion in the brain.1,11–14

Using Time-SLIP, we detected several CSF flow patterns that could not be resolved by traditional imaging. Time-SLIP allowed us to visualize unique CSF flows in different spinal regions, each of which likely reflected a different path through the septum of the syrinx.

There are several hypotheses related to syrinx formation,15–20 and the use of Time-SLIP in the present study has significantly advanced the understanding of syrinx formation. Specifically, we observed fast flow at the head of syrinx in our case. Pulsatile flow was observed through the aqueduct to the syrinx, at the entry to the cavity, which indicated a direct interaction between normal CSF flow and intra-syrinx flow. Such pressure waves may induce enlargement of the fluid-filled syringomyelia cavity. This may be similar to the “slosh” theory reported by Williams.15 This new technique showed the origin of fluid in the syringomyelia cavity and revealed the driving force for cavity enlargement. At the entry to the cavity, rapid pulsatile CSF motion should be investigated during follow-up of syringomyelia patients. On the other hand we also detected slow and “non-pulsative” flow at area around caudal end within the cavity. This suggests that there was a blockage of CSF circulation at the caudal end of the syringomyelia cavity. Taken together, these findings suggest that the aqueduct is the source of CSF in syrinx formation and that obstruction of CSF flow underlies syringomyelia.15,16

Furthermore, our study provides novel information on the nature of flow interactions between cystic cavities and compartments in syringomyelia, without requiring the use of contrast medium (Fig. 4). Our findings suggest that the presence of communicating flow between syringomyelia cavities indicates the need for a shunt operation. A fluent connection between cavities may hold promise for successful resolution by means of a shunt operation. Moreover, preoperative evaluation of intra-syrinx flow dynamics using this new MRI technique may inform the planning of shunt placement.

Conclusion

Time-SLIP permitted the direct visualization of CSF flow and characterization of flow dynamics in a case of syringomyelia. This new approach will lead to a better understanding of disease pathology and may be useful in optimizing surgical planning.

References

- 1.Yamada S, Miyazaki M, Kanazawa H, Higashi M, Morohoshi Y, Bluml S, et al. Visualization of cerebrospinal fluid movement with spin labeling at MR imaging: preliminary results in normal and pathophysiologic conditions. Radiology 2008;249(2):644–52. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2492071985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishimura DG, Marcovski A, Pauly JM.. Considerations of magnetic resonance angiography by selective inversion recovery. Magn Reson Med 1988;7(4):472–84. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910070410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edelman RR, Mattle HP, Kleefield J, Silver MS.. Quantification of blood flow with dynamic MR imaging and presaturation bolus tracking. Radiology 1989;171(2):551–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.171.2.2704823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Satogami N, Okada T, Koyama T, Gotoh K, Kamae T, Togashi K.. Visualization of external carotid artery and its branches: Non-contrast-enhanced MR angiography using balanced steady-state free-precession sequence and a time-spatial labeling inversion pulse. J Magn Reson Imaging 2009;30(3):678–83. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shonai T, Takahashi T, Ikeguchi H, Miyazaki M, Amano K, Yui M.. Improved arterial visibility using STIR fat suppression in non-contrast-enhanced Time-Spatial Labeling Pulse (Time-SLIP) renal MRA. J Magn Reson Imaging 2009;29(6):1471–7. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parienty I, Rostoker G, Jouniaux F, Piotin M, Admiraal-Behloul F, Miyazaki M.. Renal artery stenosis evaluation in chronic kidney disease patients: nonenhanced Time-Spatial Labeling Inversion-Pulse three dimensional MR angiography with regulated breathing versus DSA. Radiology 2011;259(2):592–601. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito K, Koike S, Jo C, Shimizu A, Kanazawa H, Miyazaki M, et al. Intraportal venous flow distribution: evaluation with single breath-hold ECG-triggered three-dimensional half-Fourier fast spin-echo MR imaging and a selective inversion-recovery tagging pulse. Am J Roentgenol 2002;178(2):343–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.2.1780343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsukuda T, Ito K, Koike S, Sasaki K, Shimizu A, Fujita T, et al. Pre- and postprandial alterations of portal venous flow: evaluation with single breath-hold three-dimensional half-fourier fast spin-echo MR imaging and a selective inversion recovery tagging pulse. J Magn Reson Imaging 2005;22(4):527–33. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimada K, Isoda H, Okada T, Kamae T, Arizono S, Hirokawa Y, et al. Unenhanced MR portography with a half-Fourier fast spin-echo sequence and time-space labeling inversion pulses: preliminary results. Am J Roentgenol 2009;193(1):106–12. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito K, Torigoe T, Tamada T, Yoshida K, Murakami K, Yoshimura M.. The secretory flow of pancreatic juice in the main pancreatic duct: visualization by means of MRCP with spatially selective inversion-recovery pulse. Radiology 2011; 261(2):582–6. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanazawa H, Miyazaki M.. Time-spatial labeling inversion tag (t-SLIT) using a selective IR-tag on/off pulse in 2D and 3D half-Fourier FSE as arterial spin labeling. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med 2002;10:140. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyazaki M, Lee VS.. Non-contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography: state-of-the-art. Radiology 2008;248(1):20–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481071497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyazaki M, Isoda H.. Non-contrast-enhanced MR angiography of the abdomen. Eur J Radiol 2011;80(1):9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamada S, Miyazaki M, Yamashita Y, Ouyang C, Yui M, Nakahashi M, et al. Influence of respiration on cerebrospinal fluid movement using magnetic resonance spin labeling. Fluids Barriers CNS 2013;10(1):36. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-10-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner WJ, Goodall RJ.. The surgical treatment of Arnold-Chiari malformation in adults. An explanation of its mechanism and importance of encephalography in diagnosis. J Neurosurg 1950;7(3):199–206. doi: 10.3171/jns.1950.7.3.0199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams B. On the pathogenesis of syringomyelia: a review. J R Soc Med 1980;73(11):798–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greitz D, Ericson K, Flodmark O.. Pathogenesis and mechanics of spinal cysts. A new hypothesis based on magnetic resonance stdies of cerebrospinal fluid dynamics. Int J Neuroradiol 1999;5(2):61–78 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klekamp J. The pathophysiology of syringomyelia-historical overview and current concept. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;144(7):649–64. doi: 10.1007/s00701-002-0944-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koyanagi I, Houkin K.. Pathogenesis of syringomyelia associated with Chiari type 1 malformation: review of evidences and proposal of a new hypothesis. Neurosurg Rev 2010;33(2):271–85. doi: 10.1007/s10143-010-0266-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heiss JD, Snyder K, Peterson MM, Patronas NJ, Butman JA, Smith RK, et al. Pathophysiology of primary spinal syringomyelia. J Neurosurg Spine 2012;17(5):367–80. doi: 10.3171/2012.8.SPINE111059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]