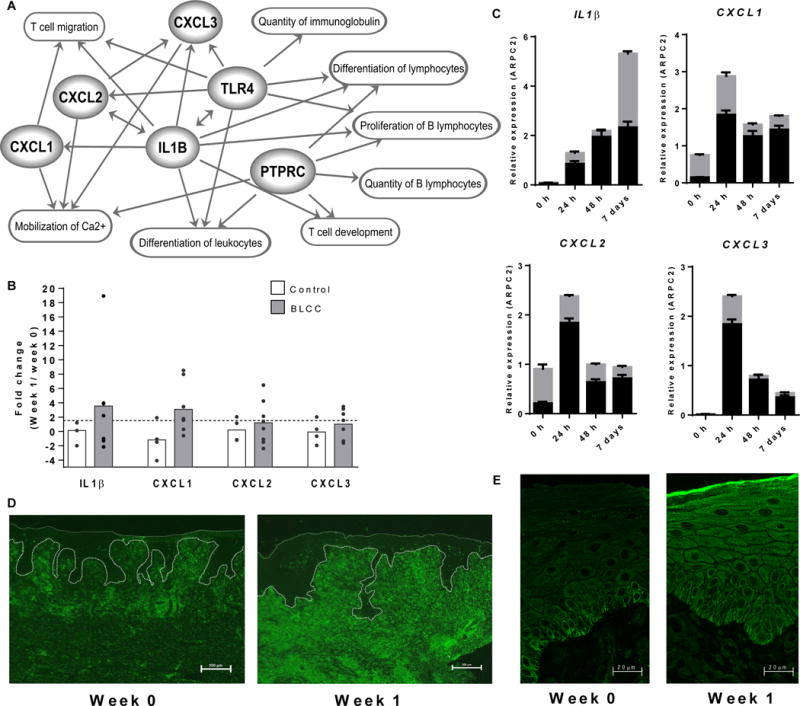

Fig. 6. Recapitulation of immune features of the acute wound healing phenotype in chronic VLUs following BLCC treatment.

(A) Interplay of genes and biological functions jointly enriched in acute wounds (n=6) and in BLCC-treated VLUs (n=6). Links (arrows) are based on IPA-categorized literature findings. (B) qPCR expression of IL1B, CXCL1, CXCL2 and CXCL3 in non-healing VLUs one week after standard of care compression therapy (control, n=4, unshaded bars) or compression therapy plus BLCC (n=8, shaded bars). Dots represent fold expression change in individual paired samples one week post treatment, with bar height at the group mean. See also fig. S4. (C) IL1B, CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL3 expression in an ex vivo model of acute wound healing in skin from n=2 healthy donors, as determined by qPCR at 0, 1, 2, and 7 days post-wounding. Gray and black bars represent expression in individual donors (mean ± SEM of n=3 technical replicates). (D) PTPRC-encoded CD45 receptor immunofluorescence staining of wound edge sections before (week 0) and after (week 1) BLCC treatment. Scale bar, 200 um. (E) Immunofluorescence staining of wound edge sections for epidermal TLR4 expression before (week 0) and after (week 1) BLCC treatment. Scale bar, 20 um. Images in D–E are representative of n=5 study subjects before and after BLCC application (Week 0 vs. Week 1).