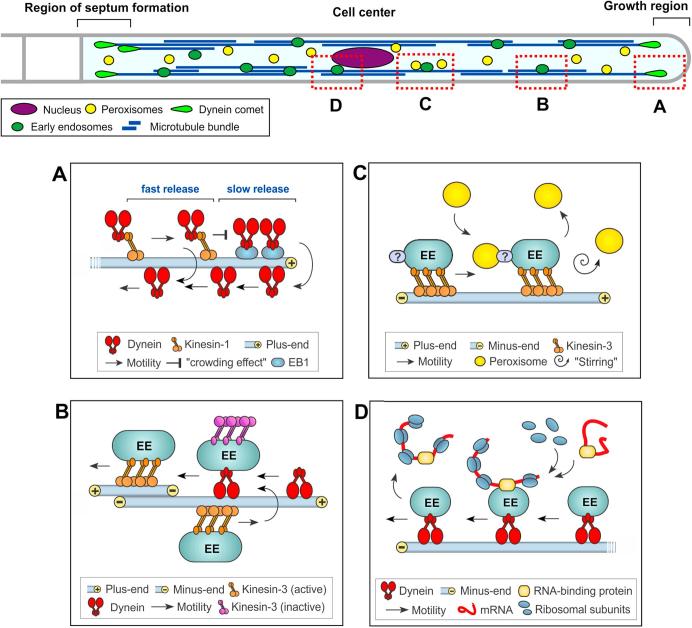

Fig. 1.

Aspects of intracellular motility that have been investigated using mathematical modelling. Top panel shows a schematic drawing of a hyphal cell of U. maydis. The cell grows are one pole (“Growth region”), while septa are continuously formed at the other end (“Region of septum formation”). Microtubule bundles run along the length of the hyphal cell. They are utilized by the molecular motors kinesin-3 and dynein, which transport organelles (such as early endosomes and peroxisomes) in a bi-directional fashion (Steinberg, 2011, Steinberg, 2016). Mathematical modelling helps to elucidate the mechanism and cellular role of these trafficking (red dotted boxes A–D): A: Kinesin-1 delivers dynein to the polar plus-ends of MTs, where dynein accumulates in a “dynein comet”. This comet consists of ∼55 dynein motors and is formed by an active, EB1-based retention and a “crowding effect” of stochastic motion of motors at MT plus-ends identified from mathematical modelling. Observation of native dynein motors reveals that two dynein populations in the comet are released at different rates. Further details can be found in Schuster et al. (2011a). B: The MT array consists of uni-polar regions near the cell ends and anti-polar bundles near the center. 3–4 kinesin-3 motors take early endosomes to the microtubule plus-ends. During this delivery, dynein motors, released from the “comet” can bind to the organelles. This appears to inactivate the kinesin-3 motors, which can take over again within the region of anti-polar bundling. This change to kinesin-3-based transport requires the release from dynein. Such a mechanism is also supported by mathematical modelling. Further details can be found in Schuster et al., 2011b, Schuster et al., 2011c. C: Early endosomes constantly move in a bi-directional fashion (only plus-directed moving early endosomes are shown), thereby generating turbulences (“stirring”) in the cytoplasm which enhance the diffusion (so called as “active diffusion”) of organelles, such as peroxisomes and lipoid droplets (only peroxisomes are shown). In addition, both organelles can transiently bind to moving early endosomes via unknown linker proteins (“?”). Modelling reveals that the combination of active diffusion and dragging of peroxisomes ensures mixing and even distribution of the organelles in the fungal cell. Further details can be found in Lin et al., 2016, Guimaraes et al., 2015. D: Transient binding to early endosomes is also required to distribute entire polysomes. These structures are constantly formed at the nucleolus. After export from the central nucleus into the cytoplasm, transient binding to moving endosomes (only minus-directed moving early endosomes are shown) via the RNA-binding protein Rrm4 (Becht et al., 2006) ensures their distribution in the cell. Mathematical modelling reveals that this “hitchhiking” mechanism is required for even distribution of the protein translation machinery. Further details can be found in Higuchi et al. (2014).