Abstract

The phenomenon of de novo gene birth from junk DNA is surprising, because random polypeptides are expected to be toxic. There are two conflicting views about how de novo gene birth is nevertheless possible: the continuum hypothesis invokes a gradual gene birth process, while the preadaptation hypothesis predicts that young genes will show extreme levels of gene-like traits. We show that intrinsic structural disorder conforms to the predictions of the preadaptation hypothesis and falsifies the continuum hypothesis, with all genes having higher levels than translated junk DNA, but young genes having the highest level of all. Results are robust to homology detection bias, to the non-independence of multiple members of the same gene family, and to the false positive annotation of protein-coding genes.

Introduction

It has become clear that protein-coding genes can originate de novo from non-coding sequences1. This is surprising, because amyloid is a generic structural form of any polypeptide, making the expression of random polypeptides a dangerous affair2. De novo gene birth is a radical evolutionary transition, and two hypotheses have previously been presented to explain how it is possible. The “continuum” view posits that there is a series of intermediate stages, or “proto-genes”, between non-genes and genes3. In contrast, the “preadaptation” theory posits that de novo birth is an all or nothing transition to functionality, and the key to successful innovation is the imperative to avoid the most toxic “hopeless monster” options in favor of “hopeful monsters”4–6; given a marker for such avoidance, newborn genes will therefore have exaggerated, rather than intermediate, gene-like characteristics. In other words, newborn gene birth occurs only from sequences that happen to be pre-adapted to “first, do no harm” in the most direct way possible. Only later do they adapt to protect themselves against risks in subtler ways, increasing tolerance with respect to other more subtle characteristics7.

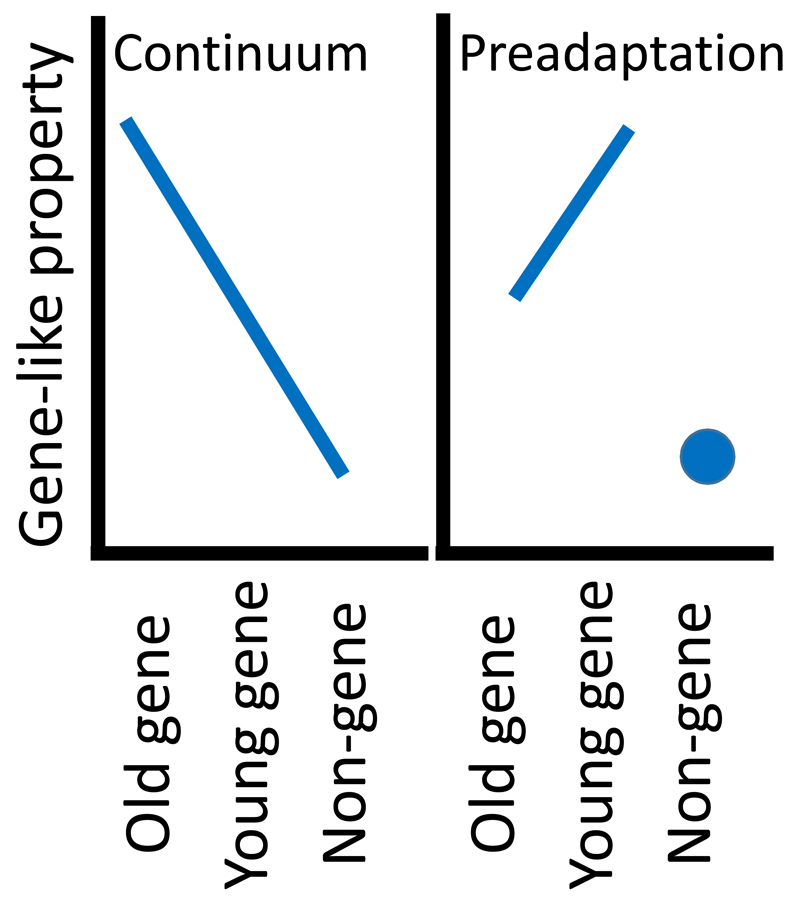

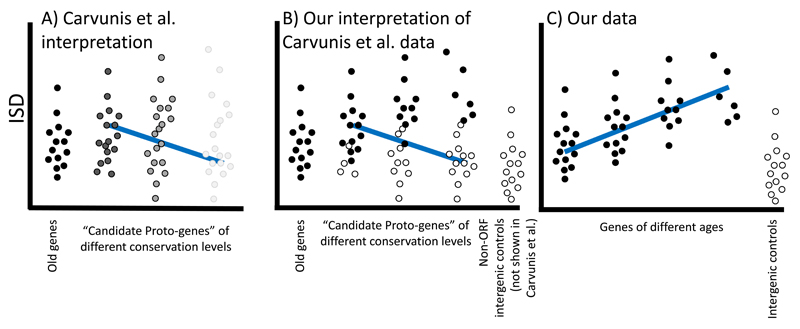

These two theories can be empirically distinguished, given a simple trait that systematically makes proteins less likely to be harmful. According to the continuum theory, the trait should be strongest in old genes, intermediate in young genes, and weakest in non-coding sequences. According to the preadaptation theory, the trait should be strongest in young genes, intermediate in old genes, and weakest in non-coding sequences (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The continuum and preadaptation hypotheses make incompatible predictions about the properties of intergenic sequences relative to young vs. old genes.

A good candidate trait is the degree of intrinsic structural disorder (ISD), i.e. the degree to which a given peptide folds as a stable three-dimensional structure (i.e., ordered) vs. as a rather flexible and unstructured entity (i.e., disordered)8. Predicted levels of ISD can conveniently be calculated from sequence alone9. Natural protein sequences are more intrinsically disordered than random sequences10. Meantime, there is conflicting evidence as to whether young genes are more or less disordered than old genes. Elevated ISD is found in orphan domains and recent extensions to domains11–14. Elevated ISD was found in complete orphan genes in Leishmania15, and in genes created de novo in alternative reading frames of existing viral genes16, but low ISD was found in Saccharomyces orphan genes3,13.

In this study, we stratify genes in two distantly related eukaryotic organisms, the house mouse and baker’s yeast, by age, and use predicted ISD values to show that young genes do not behave like intermediates between non-genic sequences and older genes as predicted by a continuum theory. Instead, young genes have exaggerated gene-like structural properties, as expected from sequences biased by the demands of preadaptation.

Results and Discussion

We rigorously determine how ISD depends on gene age in mice, using a phylostratigraphy approach17 to assign ages to genes. We exclude genes unique to a single species, as these are likely to be contaminated with many false positives that are not protein-coding genes at all. Mouse is a good choice of taxon because of the quality of its gene annotation and the large number of genome sequences available for closely related species7, which together provide temporal resolution among young protein-coding genes. The rarity of horizontal gene transfer in the ancestors of mouse is also an important consideration.

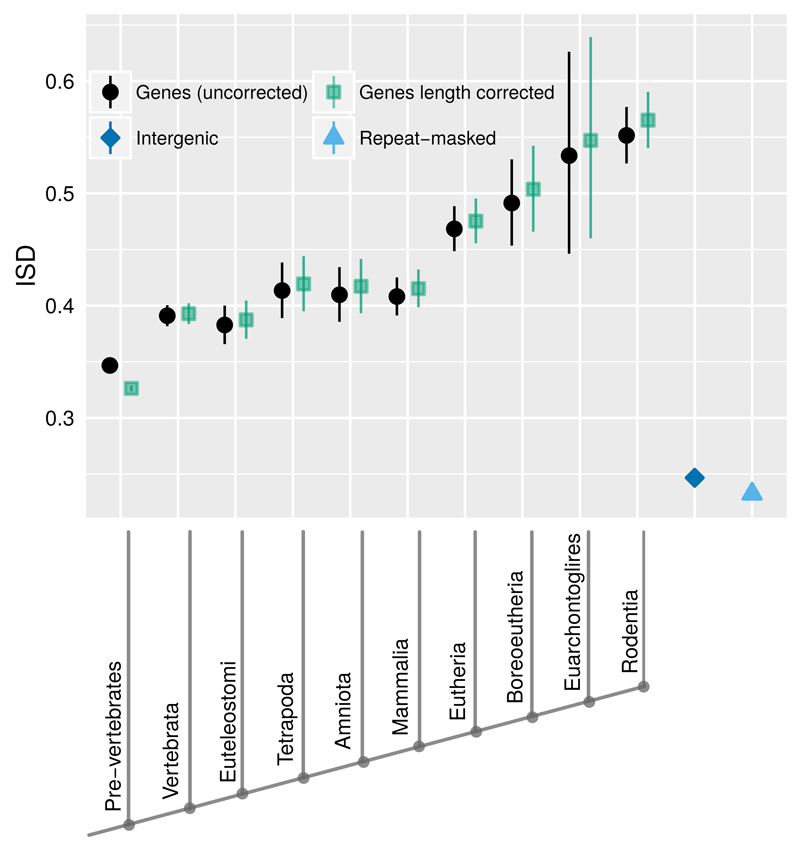

We find that young mouse genes have higher ISD (Fig. 2). Our statistical analysis avoids pseudoreplication in the form of phylogenetic confounding among multiple members of the same gene family, by controlling for gene family as a random effect within a linear model; this is not a technique we have previously encountered in related literature.

Fig. 2. Young genes have higher ISD (black circles) than old genes.

This result from the analysis of 15,347 mouse genes is unchanged by correction for evolutionary rate, and only becomes stronger after correction for length (green squares). Back-transformed central tendency estimates +/- one standard error come from a linear mixed model, where gene family, phylostratum, and length are random, fixed, and quantitative terms respectively. Importantly, this means that we do not treat genes as independent data points, but instead take into account phylogenetic confounding, and use gene families as independent data points. Length-corrected ISD values are with respect to a standardized length of 179 amino acids. Both young genes and old genes have higher ISD than intergenic sequences (blue diamond) and repeat-masked intergenic sequences (light blue triangle). Phylostrata on the x-axis are labeled according to the clade in which the oldest detectable homolog of a gene can be found. To minimize homology detection bias, the oldest phylostrata have been condensed into a single Pre-vertebrate phylostratum.

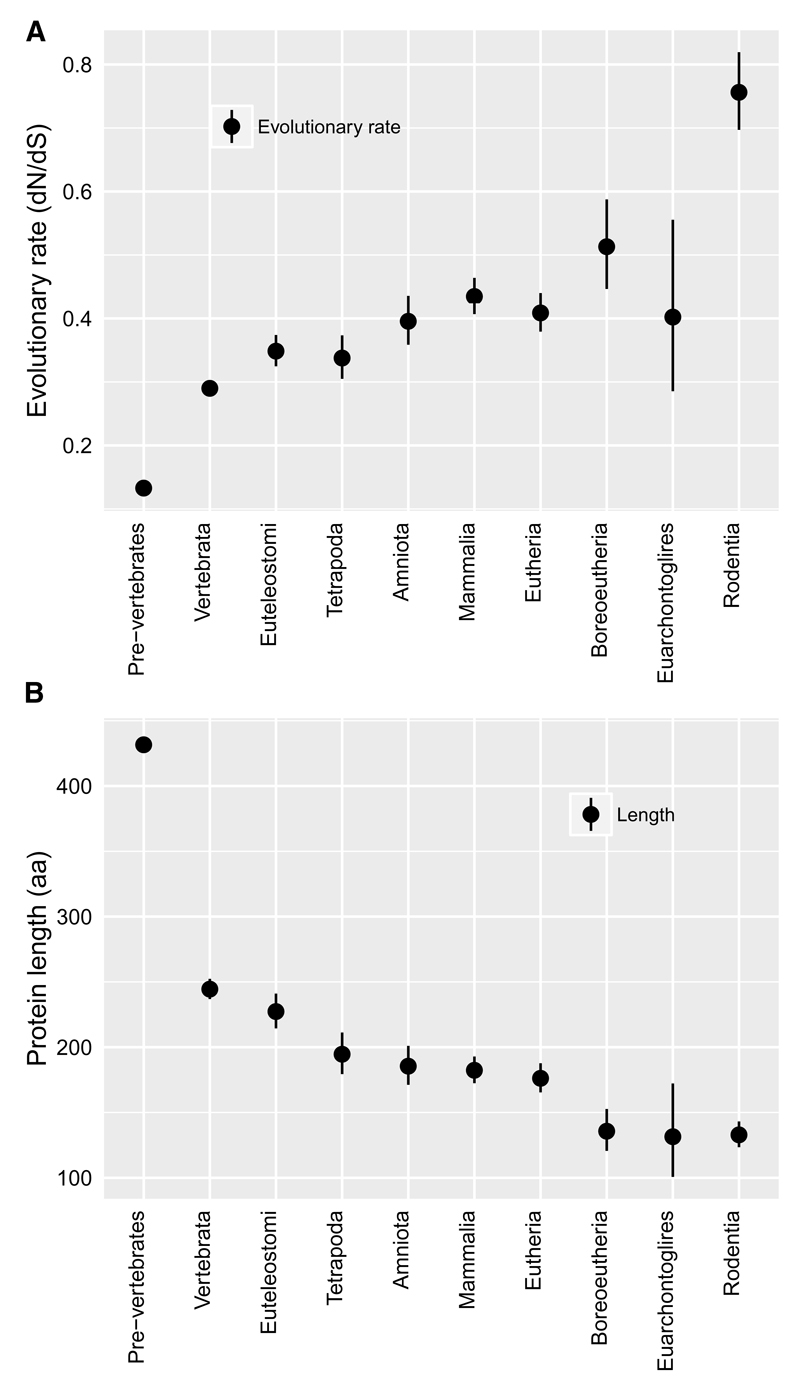

The validity of phylostratigraphy has been challenged on the grounds of homology detection bias18–20. Disordered proteins evolve faster15,21,22; if this makes homology undetectable, then high ISD could cause young gene status, rather than young gene status being the cause of high ISD23. Homology detection bias is minimized by focusing on the youngest genes20; we therefore collapsed all pre-vertebrate phylostrata into a single “old gene” category, in order to focus on gene ages with the least homology detection bias. What is more, correcting for the influence of evolutionary rate, via a linear regression analysis, had no effect on the predictive power of gene age (p>0.05), despite the fact that evolutionary rate and age are correlated (Fig. 3A). Both proponents24 and detractors18,19 of phylostratigraphy have used simulations of protein evolution to justify their position on the impact of homology detection bias – unfortunately, this line of argument relies on our ability to model protein evolution realistically. Our more empirical approach suggests low impact, in a more direct and less model-dependent fashion.

Fig. 3. In agreement with many previous studies, young genes evolve faster (A) and are shorter (B).

These properties are directly causal for homology detection bias, and hence there is no way to produce bias-corrected values as for Fig. 2. However, the statistical insignificance of rate-correction in Fig. 2 suggests that homology detection bias is negligible. Back-transformed central tendency estimates +/- one standard error come from a linear mixed model, where gene family and phylostratum are random and fixed terms respectively.

Homology is also easier to detect for longer genes, and in agreement with previous findings7, length and age are correlated (Fig. 3B). However, longer genes have higher ISD as scored with IUPred, with quite large effect sizes – we find a Pearson correlation coefficient (following transformation for normality) of 0.17 for old genes, and in the range 0.32-0.44 within newer phylostrata. Using a linear model to correct for the length-ISD relationship therefore makes our ISD-age relationship stronger not weaker (Fig. 2, green).

Note that our ISD scores strongly reflect amino acid composition, with low ISD representing hydrophobicity. In this light, our findings agree with previous results on length-dependent frequencies of particular amino acids25, but contradict previous studies, restricted to single-domain globular proteins, that showed no length-dependence for hydrophobicity as a whole26,27. Using the Irbäck and Sandelin26 hydrophobicity measure on our more comprehensive protein set, we continue to find that long genes have more hydrophilic amino acids (Pearson correlation coefficients only slightly lower, at -0.13 for old genes, and in the range –(0.24–0.45) within new phylostrata).

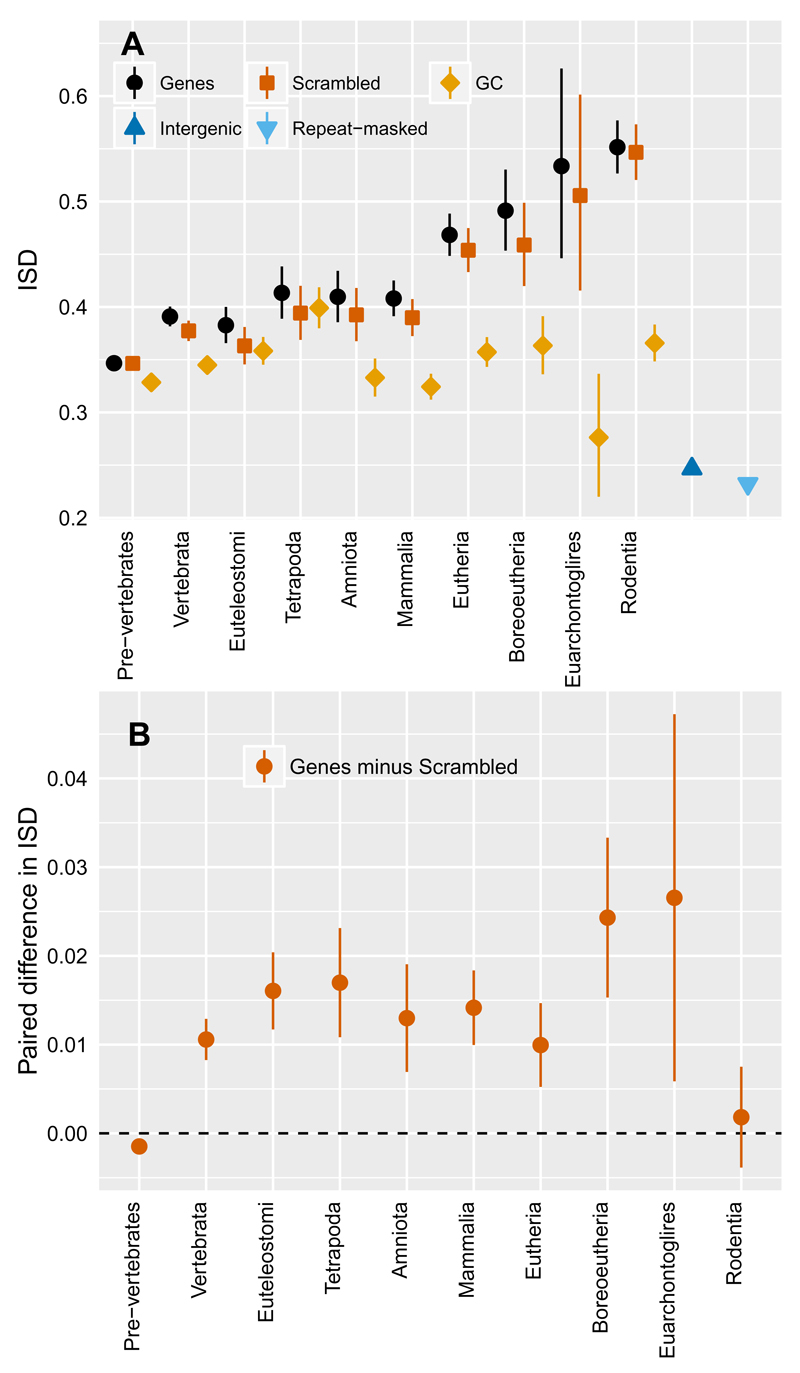

The high ISD of young genes is primarily due to amino acid composition (calculated as the ISD of scrambled versions of a gene; Fig 4A, orange) rather than the exact order of the amino acids (calculated as the difference between the ISD of the real gene and that of a scrambled control; Fig. 4B). This suggests that genes are born with high ISD, driven by amino acid composition. Amino acid composition can therefore be seen as a preadaptation28, or “non-aptation” in the terminology of Gould and Vrba29, for de novo gene birth. This does not imply any kind of pre-adaptive process of the kind postulated elsewhere4–6,30. Instead, the term preadaptation simply refers to backward-time conditional probability; given that gene birth occurred, the non-coding sequence from which the gene was born is likely to have had more favorable characteristics for gene birth than the average non-coding sequence. Note that while higher GC content leads to higher ISD31, GC content is not the primary driver of the high ISD-promoting amino acid composition of young genes (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4. Elevated ISD can be broken down into contributions from amino acid contribution and from exact amino acid order.

(A) ISD in real proteins (black circles) relative to amino acid scrambled controls (orange squares), and controls generated to have matched GC content (yellow diamonds), with error bars showing the back transform of the central tendency estimates +/- 1 standard error derived from mixed models as in Fig. 2. Excess ISD is driven primarily by amino acid composition, not GC content or precise amino acid order. (B) Paired comparisons show that the small excess in ISD relative to that predicted from amino acid composition is statistically significant (95% confidence intervals are shown) in all young genes except the very youngest, despite the broad confidence intervals in (A) that do not take into account the paired nature of the data.

In contrast, the contribution of amino acid order to ISD appears to be an adaptation rather than a preadaptation in young genes (those born in vertebrates), because it is not initially present but appears only after some time. This contributes an independent line of evidence that high ISD values are favored in young genes.

Now that we have determined how ISD depends on gene age, the non-coding sequences from which de novo proteins must be born allow us to distinguish between the continuum and preadaptation hypotheses. The continuum theory predicts that non-coding sequences will resemble exaggerated versions of young genes, and hence have the highest ISD. In contrast, the preadaptation theory expects young genes to show the most extreme deviation from random sequences, predicting that non-coding sequences will have the lowest ISD.

We sampled intergenic sequences near each mouse gene in our analysis as representative of the raw material from which de novo genes are born, rather than analyzing randomly generated sequences matching only a subset of known variables, such as GC-content31. Our intergenic controls reflect the subtleties found in a real genome with a complex evolutionary history, e.g. the avoidance of CpG sites. We find strong evidence refuting the continuum hypothesis and supporting the preadaptation hypothesis (Fig. 2). This result is not attributable to repetitive sequences; results are nearly identical when RepeatMasker is used to filter the intergenic control sequences (Fig. 2). The size of the gap between the average ISD of a translated intergenic sequence and that of young genes strikingly illustrates the nature of the filter applied during de novo gene birth, and the relevance of ISD to the process.

Why then did a previous yeast study3 find that young genes and “proto-genes” have low ISD? We believe that the difference lies in the annotation procedure. Our study included only genes with BLASTp homology across at least two species, whereas the previous study accepted BLASTn homology, which might result in homologous non-coding sequences being scored as protein-coding genes. When there is a mixture of true protein-coding genes combined with sequences that do not encode a functional polypeptide, the mean of the entire mixture will of course be intermediate between the means of the two groups. The overall mean will depend strongly on the ratio between the two components. Specifically, if the proportion of non-functional ORFs decreases with conservation level, then a continuum will automatically be observed, and in the wrong direction as a function of apparent gene age. Fig. 5 illustrates, in context, the statistical problem known as Simpson’s paradox32, which drives this effect.

Fig. 5. Putative evidence for the continuum hypothesis can be explained as a statistical artefact known as Simpson’s paradox.

A) The continuum view posits the existence of “proto-genes” that have “characteristics intermediate between non-genic ORFs and genes”3. Candidate proto-genes were classified on the basis of being annotated as ORFs, and having detectable sequence homology in sister species (without necessarily retention of approximate ORF boundaries), and Carvunis et al (2012) claimed to show a continuum of properties as a function of conservation level, shown as a greyscale. B) The same data can be explained without resorting to the existence of such intermediates. Sequence homology for ORFs that are not protein-coding genes (white circles) becomes more difficult to detect as a function of age, such that the proportion of true genes (black circles) increases with age, giving rise to the same observations as A. The downward trend in ISD arises as an example of Simpson’s paradox32. C) By carefully excluding all non-genes, we see the true relationship between gene age and ISD, and compare it to intergenic control sequences that are definitely not protein-coding genes. Note that if true protein-coding genes were excluded in B (rather than excluding non-genes as in C), there would be no relationship with conservation levels.

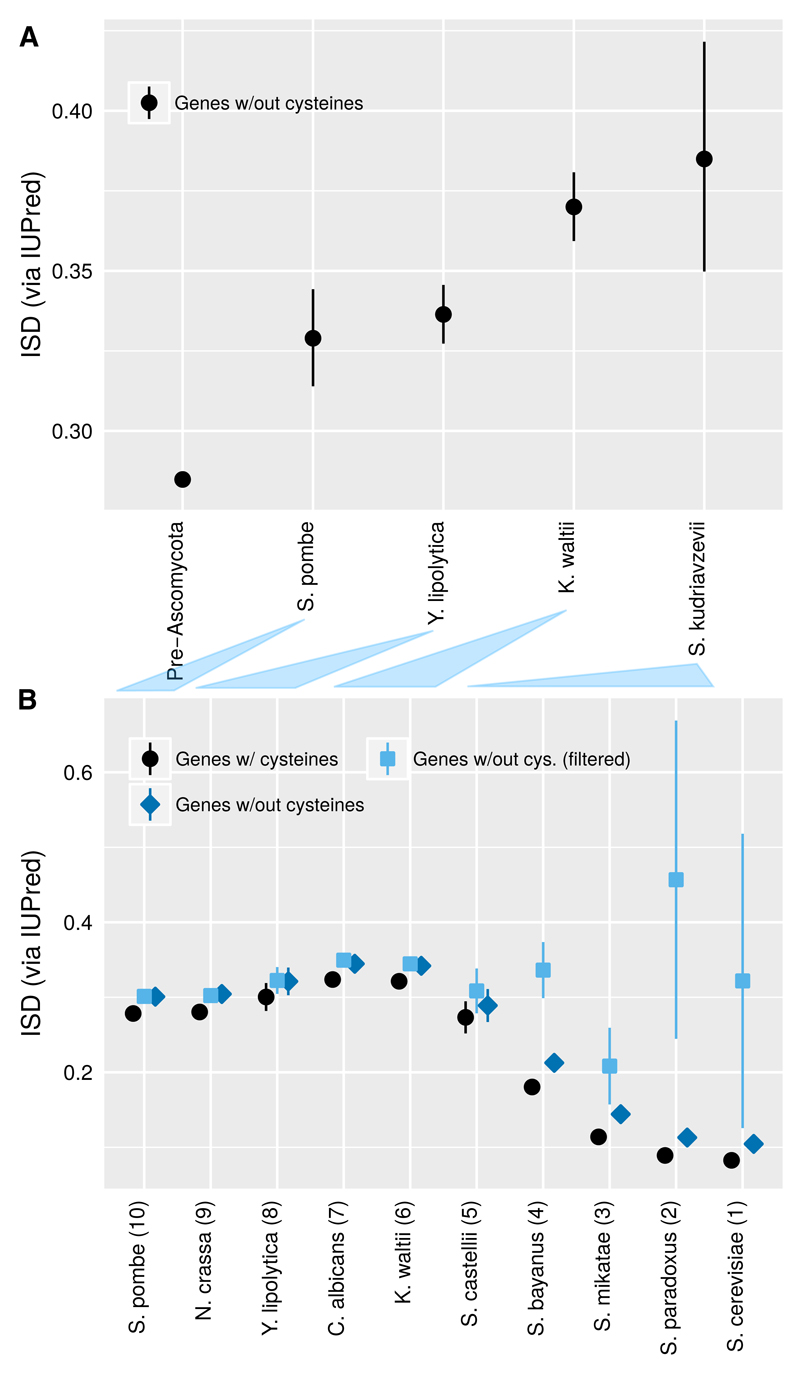

To confirm that this is responsible for the discrepancy, we repeated our mouse pipeline on yeast (Fig. 6A) and confirmed that following our methods, young yeast genes, like young mouse genes, have higher ISD. To pinpoint the source of the discrepancy, we used the gene age classifications of Carvunis et al. (personal communication of dataset), and omitting gene families from the analysis, reproduced the previously reported trend of low ISD in young “proto-genes” (Fig. 6B, black). Details such as the treatment of disulfide bonds made no substantive difference (Fig. 6B, dark blue). However, filtering out potentially non-coding sequences eliminated the previously reported trend (Fig. 6B, light blue). Details of the elimination criteria are shown in Table 1; the preferential elimination of younger phylostrata is consistent with the operation of Simpson’s paradox. Fig. 6 shows that the differences between our conclusions and those of Carvunis et al.3 are due to the categorization of what is a gene, not to the details of the ISD calculations or of how genes are assigned to phylostrata. In both our mouse and yeast analyses, we were careful to discard all possible non-genes, leaving us looking at a single group and not a mixture in each phylostratum. Mouse has more well-verified young protein-coding genes, allowing for clearer resolution of ISD at shorter timescales.

Fig. 6. Young yeast genes, like the young mouse genes in Fig. 2, have higher ISD.

A) Back-transformed central tendency estimates +/- one standard error come from a linear mixed model, where gene family and phylostratum are random and fixed terms, respectively. Phylostrata are labeled according to the species most closely related to S. cerevisiae in which a homolog is still found, except for the “S. kudriavzevii” group, which includes younger genes found in at least two species. The analysis includes 5452 yeast genes that overlap with the genes used by Carvunis et al. (2012) with filtering indicated in Table 1. B) Using the age classifications of Carvunis et al. (2012) (Table 1, 2nd column), and ignoring gene family, we reproduce the trend of low ISD in young “proto-genes” using our slightly different ISD measurement. Standard means +/- one standard error are reported for untransformed ISD estimates. This trend is insensitive to whether cysteines are included (black circles) or excluded (blue diamonds) from the protein primary sequence. This trend disappears when we screen out “proto-genes” that lack strong evidence for a functional protein product (light-blue squares), by excluding genes whose age we could classify or which were unique to S. cerevisiae, and those classified as “dubious” in SGD (Table 1; last column). Correspondences between the ages assigned by the two phylostratigraphies are indicated with shaded triangles between the two figure parts.

Table 1.

Number of genes assigned to each of the “Conservation Levels” annotated by Carvunis et al.3.

| Conservation level | Genes matching our dataset | After excluding dubious genes | After excluding genes that we found to be unique to S. cerevisiae | After excluding genes whose age we were unable to classify |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (S. cerevisiae) | 143 | 35 | 3 | 2 |

| 2 (S. paradoxus) | 172 | 44 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 (S. mikatae) | 137 | 31 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 (S. bayanus) | 325 | 162 | 28 | 27 |

| 5 (S. castellii) | 94 | 88 | 53 | 53 |

| 6 (K. waltii) | 511 | 501 | 489 | 489 |

| 7 (C. albicans) | 411 | 405 | 398 | 398 |

| 8 (Y. lipolytica) | 81 | 79 | 78 | 77 |

| 9 (N. crassa) | 499 | 491 | 483 | 482 |

| 10 (S. pombe) | 3935 | 3925 | 3918 | 3918 |

Note that if a continuum of increasing ISD with age were to take place at short time scales only (a less parsimonious hypothesis than ours, and one that Simpson’s paradox would make difficult to confirm), our mouse analysis restricts it to, at most, the last ˜21-82 million years, before the split of mouse and rat and after the split of mouse and rabbit. In contrast, the continuum of ISD scores reported in Carvunis et al.3 is claimed to go all the way back to the split between S. cerevisiae and C. albicans (˜300 million years), despite the much shorter generation times of yeast.

Fig. 5 shows that the existence of intermediate “proto-genes” is not necessary to explain data on trends in mean properties. What is more, the very concept of a “proto-gene” as intermediate between gene and non-gene is problematic, with inappropriately teleological connotations. However, as a non-teleological definition, it may be useful to refer to slightly-expressed but non-functional ORFs as “proto-genes”. ORFs, i.e. stretches between a start codon and a stop codon in a transcript, occur frequently by chance. ORFs that encode highly deleterious polypeptides, and that are translated at low levels, are purged from a population more rapidly than relatively harmless ORFs, and this fact could help explain the phenomenon of de novo gene birth6. Pervasive transcription subject to rapid evolutionary turnover33, and leading to non-functional translation6, provides the raw materials for proto-genes defined in this fashion. However, it must be noted that even harmless ORFs, in the absence of selection for some beneficial property, are rapidly disrupted by mutation. There is therefore a discrete dichotomy between the states of “gene” and “non-gene”, determined by whether the selection coefficient is greater than zero, and hence capable of sustaining their continued existence in the face of mutational onslaught34. A dichotomy of functionality (defined in evolutionary terms) is still compatible with the idea that some non-genes are under selection that weeds out the most deleterious of options, in a manner that promotes evolvability4,5.

In terms of the adaptive potential of non-coding sequences, while even the young genes have much higher ISD on average than found in sequences translated from randomly chosen junk DNA, these averages conceal considerable variation, with greater variation among gene families than among intergenic sequences35 (see Supplementary Figure 1), suggestive of diversifying selection. 12.7% of our intergenic sequences yield ISD levels within the range of the highest 75% of all genes in the youngest phylostratum considered here, creating relatively little barrier to de novo gene birth. On the surface, protein length would appear to be a stronger constraint – only 25% of annotated young genes are less than 108 amino acids long, far longer than expected by chance in junk DNA – although biases in gene annotation may mean that typically young genes encode, in reality, even shorter proteins.

Once proteins are born with a given ISD, evolutionary tinkering and differential loss seem to change ISD only slowly, resulting in the consistent trend seen over hundreds of millions of years in Fig. 2. While gene birth is a sudden transition to functionality, subsequent descent with modification can generate extraordinarily slow trends.

Methods

M. musculus proteins from Ensembl (v75)36 were subjected to a BLASTp37 search with an E-value threshold of 0.001 20 against the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nr database (June 2014). The most phylogenetically distant hit was used to place the gene into one of the 20 phylostrata (gene ages) listed in Table S1, following Dollo’s parsimony and neglecting horizontal gene transfer. 126 from 22,778 available protein sequences could not be successfully assigned to any phylostratum due to BLASTp-related problems such as too short queries, majority of query composed of low-complexity sequences, or a combination of both. These sequences were not considered for further analysis.

In order both to remove dubious genes and to perform evolutionary rate controlled ISD estimates, dN/dS values were downloaded for all mouse proteins from the Ensembl BioMart38 (accessed February 18, 2016) and mapped to our dataset using the Ensembl protein ID. Evolutionary rates were calculated using PAML by comparing all mouse proteins with their orthologs in rats. Genes with no rat ortholog of amino acid sequence identity greater than 50% were excluded, leaving 17,762 non-orphan mouse genes, all with dN/dS values, for further study. When rat had multiple orthologs meeting this quality filter, the one with the highest rate was taken (to prevent any further exclusion of genes with high evolutionary rate, beyond the low bar of detectable mouse-rat homology). Restricting analysis to one-to-one orthologs did not qualitatively change the results.

Pairwise paralog information among non-orphan mouse genes was taken from Ensembl, from which gene families were constructed via a single-link cluster analysis. This yielded 8124 gene families, 7113 of which showed complete agreement among their member genes regarding age. Of the remainder, 824 gene families contained genes assigned to exactly two different phylostrata: 526 of these had only a single gene in the younger phylostratum, which was reassigned back to the older phylostratum. Of the remainder split across exactly two phylostrata, 150 had only a single older member, which we reassigned to be younger, leaving 148 gene families unclassified. In addition, 187 gene families contained genes split among more than 2 phylostrata, of which 86 could similarly easily be reconciled by discounting the gene age status of singletons, leaving another 101 gene families unclassified. Most of the 249 gene families with unclassified ages are split between multiple old phylostrata: since we had no shortage of data in these older phylostrata, and since this group includes complex scenarios such as gene fusion and repetitive sequences, these gene families were excluded from further analysis, leaving 15,347 total genes for our analysis.

Twenty six gene families, consisting of 29 M. musculus genes, did not originally return NCBI nr BLAST hits outside their own species, yet Ensembl reported dN/dS values relative to a rat ortholog that met our sequence identity filter. Fourteen of the genes also returned this rat ortholog from NCBI’s nr database as of August 2016. A sample of those that did not return the rat ortholog nevertheless passed manual inspection of the protein-coding status of the Ensembl-identified ortholog. These were therefore assigned to the Rodentia phylostratum.

Our single-link clustering plus cleanup procedure to construct gene families produced a much better fit to the data than treating genes as independent, explaining far more variance than phylostratrum, the property of interest (ΔAIC=114 removing phylostratum from the model vs. ΔAIC=9,928 removing the random effect of gene family from the model).

We calculated ISD using IUPred9, after first excising all cysteines from the protein sequence (from Ensembl v.73), because of uncertainty about their disulfide bond status combined with a profound impact of disulfide bond status on ISD39. For each gene, we averaged the ISD across all other amino acids, and performed a Box-Cox transformation (λ = 0.66, λ optimized using only coding genes not controls) prior to linear model analysis. Central tendency estimates and confidence intervals were then back transformed for the plots.

Protein lengths were approximately log-transformed (Box-Cox λ = -0.0432). Hydrophobicities were calculated first for amino acids: leucine, isoleucine, valine, phenylalanine, methionine, and tryptophan were scored as +1, and all other amino acids were scored as -1. Then the mean hydrophobicity for a protein was used to examine the length-dependence of amino acid composition.

For each gene, we generated scrambled controls by resampling amino acids without replacement. To generate GC-matched controls, the numbers of GC and AT nucleotides were calculated excluding the stop codon, then GC vs AT identity was resampled without replacement, and then G vs C and A vs T were assigned at 50% probability. If a premature stop codon arose, one of the three stop codon nucleotides was switched with another nucleotide position chosen at random. This process was iterated until no premature stop codons remained, and then a stop codon was appended to the end.

To generate one intergenic control per gene, we took one intergenic sequence 100nt downstream from the end of the 3' end of the Ensembl v80 annotation of the transcript, and progressed further, excising stop codons along the way, until a length match to the neighboring protein-coding gene was obtained. We then obtained a second control sequence near each gene, by repeating the process after starting a search 100nt further downstream. For the RepeatMasked40 controls, intergenic sequences further downstream were used as necessary in order to extract the control sequence from a contiguous non-masked intergenic sequence.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae genes taken in June 2014 from the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD)41 were assigned gene ages according to the procedure described above for mouse. We supplemented our phylostratigraphic analysis of species supported by the NCBI taxonomy browser with a selection of more closely related yeast species; our youngest phylostratum contains any S. cerevisiae genes with a homolog found in S. kudriavzevii (in most cases) or in a still more closely related yeast species (for a handful of genes). As for M. musculus, we constructed gene families using single-link cluster analysis on pairwise paralog information from Ensembl, and the ages of single discordant genes were reconciled as described above with the other age assignments within their gene family. Genes classified by us as specific to S. cerevisiae were excluded from many analyses, as were genes that we failed to classify using BLAST, and those classified as “dubious” in SGD. “Conservation Level” (an alternative phylostratigraphy that includes BLASTn homology detection) was provided via personal communication to reproduce the classification presented by Carvunis et al.3. ISD values were calculated as for mouse except with Box-Cox λ = 0.554.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Work was supported by the John Templeton Foundation (39667), the National Institutes of Health (GM104040) and ERC grant NewGenes (322564). We thank Diethard Tautz and Matt Cordes for insightful discussions, Robert Bakaric for assistance with phylostratigraphy, and Anne-Ruxandra Carvunis for comments on a draft of the manuscript and for sharing data.

Footnotes

Source data and code availability: Source data for the statistical analyses and figures are provided in Supplementary Tables 2-7. Code associated with generating and analyzing these tables is publicly available at https://github.com/MaselLab.

Author contributions: J.M and R.N. conceived the approach, R.N. performed the phylostratigraphy, B.W. and S.F. completed all other data analyses, and J.M. wrote the paper.

References

- 1.McLysaght A, Guerzoni D. New genes from non-coding sequence: the role of de novo protein-coding genes in eukaryotic evolutionary innovation. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2015;370:20140332. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monsellier E, Chiti F. Prevention of amyloid-like aggregation as a driving force of protein evolution. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:737–742. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carvunis A-R, et al. Proto-genes and de novo gene birth. Nature. 2012;487:370–374. doi: 10.1038/nature11184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masel J. Cryptic genetic variation is enriched for potential adaptations. Genetics. 2006;172:1985–1991. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.051649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajon E, Masel J. The evolution of molecular error rates and the consequences for evolvability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:1082–1087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012918108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson BA, Masel J. Putatively Noncoding Transcripts Show Extensive Association with Ribosomes. Genome Biol Evol. 2011;3:1245–1252. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neme R, Tautz D. Phylogenetic patterns of emergence of new genes support a model of frequent de novo evolution. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romero P, et al. Thousands of proteins likely to have long disordered regions. Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing. Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing. 1998:437–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dosztányi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I. IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3433–3434. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu J-F, et al. Natural protein sequences are more intrinsically disordered than random sequences. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2138-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buljan M, Frankish A, Bateman A. Quantifying the mechanisms of domain gain in animal proteins. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R74. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-7-r74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore AD, Bornberg-Bauer E. The Dynamics and Evolutionary Potential of Domain Loss and Emergence. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:787–796. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ekman D, Elofsson A. Identifying and Quantifying Orphan Protein Sequences in Fungi. J Mol Biol. 2010;396:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bornberg-Bauer E, Albà MM. Dynamics and adaptive benefits of modular protein evolution. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukherjee S, Panda A, Ghosh TC. Elucidating evolutionary features and functional implications of orphan genes in Leishmania major. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;32:330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rancurel C, Khosravi M, Dunker AK, Romero PR, Karlin D. Overlapping Genes Produce Proteins with Unusual Sequence Properties and Offer Insight into De Novo Protein Creation. J Virol. 2009;83:10719–10736. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00595-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Domazet-Lošo T, Brajković J, Tautz D. A phylostratigraphy approach to uncover the genomic history of major adaptations in metazoan lineages. Trends Genet. 2007;23:533–539. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moyers BA, Zhang J. Phylostratigraphic Bias Creates Spurious Patterns of Genome Evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:258–267. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moyers BA, Zhang J. Evaluating Phylostratigraphic Evidence for Widespread De Novo Gene Birth in Genome Evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1245–1256. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albà MM, Castresana J. On homology searches by protein Blast and the characterization of the age of genes. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen SC-C, Chuang T-J, Li W-H. The Relationships Among MicroRNA Regulation, Intrinsically Disordered Regions, and Other Indicators of Protein Evolutionary Rate. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2513–2520. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Podder S, Ghosh TC. Exploring the Differences in Evolutionary Rates between Monogenic and Polygenic Disease Genes in Human. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:934–941. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Light S, Basile W, Elofsson A. Orphans and new gene origination, a structural and evolutionary perspective. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;26:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Domazet-Lošo T, et al. No evidence for phylostratigraphic bias impacting inferences on patterns of gene emergence and evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2017:msw284. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White SH. Amino acid preferences of small proteins. J Mol Biol. 1992;227:991–995. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90515-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irbäck A, Sandelin E. On Hydrophobicity Correlations in Protein Chains. Biophysical Journal. 2000;79:2252–2258. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76472-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandelin E. On Hydrophobicity and Conformational Specificity in Proteins. Biophysical Journal. 2004;86:23–30. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74080-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bock WJ. Preadaptation and multiple evolutionary pathways. Evolution. 1959;13:194–211. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gould SJ, Vrba ES. Exaptation - a missing term in the science of form. Paleobiology. 1982;8:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitehead DJ, Wilke CO, Vernazobres D, Bornberg-Bauer E. The look-ahead effect of phenotypic mutations. Biology Direct. 2008;3:15. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ángyán AF, Perczel A, Gáspári Z. Estimating intrinsic structural preferences of de novo emerging random-sequence proteins: Is aggregation the main bottleneck? FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2468–2472. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malinas G, Bigelow J. In: The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Zalta Edward N., editor. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neme R, Tautz D. Fast turnover of genome transcription across evolutionary time exposes entire non-coding DNA to de novo gene emergence. eLife. 2016;5:e09977. doi: 10.7554/eLife.09977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graur D, et al. On the Immortality of Television Sets: “Function” in the Human Genome According to the Evolution-Free Gospel of ENCODE. Genome Biology and Evolution. 2013;5:578–590. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tartaglia GG, Pellarin R, Cavalli A, Caflisch A. Organism complexity anti-correlates with proteomic β-aggregation propensity. Protein Science. 2005;14:2735–2740. doi: 10.1110/ps.051473805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flicek P, et al. Ensembl 2014. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D749–D755. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smedley D, et al. The BioMart community portal: an innovative alternative to large, centralized data repositories. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W589–W598. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Understanding protein non-folding. BBA-Proteins Proteom. 2010;1804:1231–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.RepeatMasker Open-4.0 v. 4.0.5. 2015.

- 41.Cherry JM, et al. Saccharomyces Genome Database: the genomics resource of budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D700–D705. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.