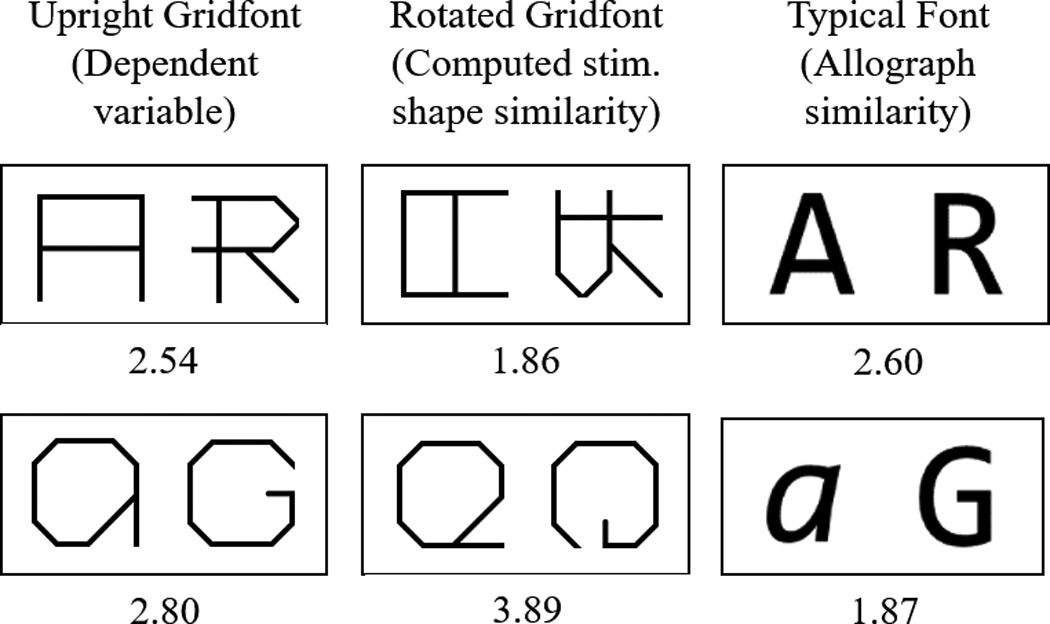

Figure 3.

Dissociating the influence of Computed Stimulus-Shape Representations from Allograph Representations. Participants made visual similarity judgments to letters presented in an atypical Upright Gridfont (left column), a Rotated Gridfont (middle column), and a Typical Font (right column). The average similarity judgment (computed from Experiment 1) is shown below each example letter-pair. A response of 1 indicates little or no visual similarity for the pair and 5 indicates the highest level of visual similarity. If computed stimulus-shape representations are the only type of letter representation that contributed to visual similarity judgments, we would predict similarity judgments for the Upright Gridfont (left column) and the Rotated Gridfont (middle column) to be identical. Instead, we see that the similarity judgments to the Upright Gridfont are different from similarity judgments to the Rotated Gridfont. The top row depicts an example where there is a bias to judge the Upright Gridfont letter-pair as being more similar than would be predicted by the computed stimulus-shape similarity alone while the bottom row shows the opposite effect. The fact that the Upright Gridfont similarity judgments are “pulled” in the direction of the Typical Font similarity judgments suggests an influence of allograph representations on these similarity judgments