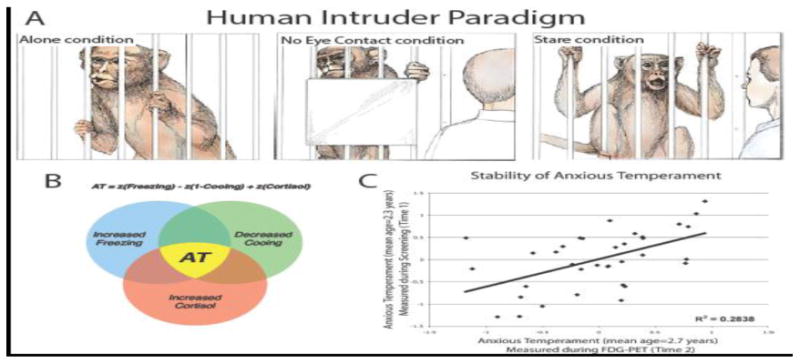

Figure 1.

(A) The three experimental conditions of the human intruder paradigm elicit distinct fear and anxiety-related behaviors in young rhesus monkeys. When alone and separated from their cagemate (Alone condition, left), young monkeys actively explore the test cage and emit “coo” calls, thought to reflect an attempt to attract help from their mothers or other conspecifics. In the next condition, a human intruder presents his or her profile, while avoiding direct eye contact with the monkey (No Eye Contact condition, center). In this situation, the monkeys typically orient their focus to the intruder, trying to evade discovery by remaining completely still (freezing) and reducing their coo volcalizations. In the third condition, the human intruder enters the room and stares at the animal (Stare condition, right). This direct threat condition elicits aggressive and submissive behaviors (e.g., barking, threatening gestures, lip smacking, and cage rattling). From Kalin (1993). Copyright 2002 by Scientific American, Inc. Reprinted by permission. (B) Anxious Temperament (AT) is calculated as the mean z-scores of NEC-induced freezing, coo vocalizations, and plasma cortisol levels. (C) AT is a relatively stable trait. In this example, taken from Fox et al. (2008), AT assessed at two time points with an approximate 4-month interval was significantly correlated. Reprinted with permission.