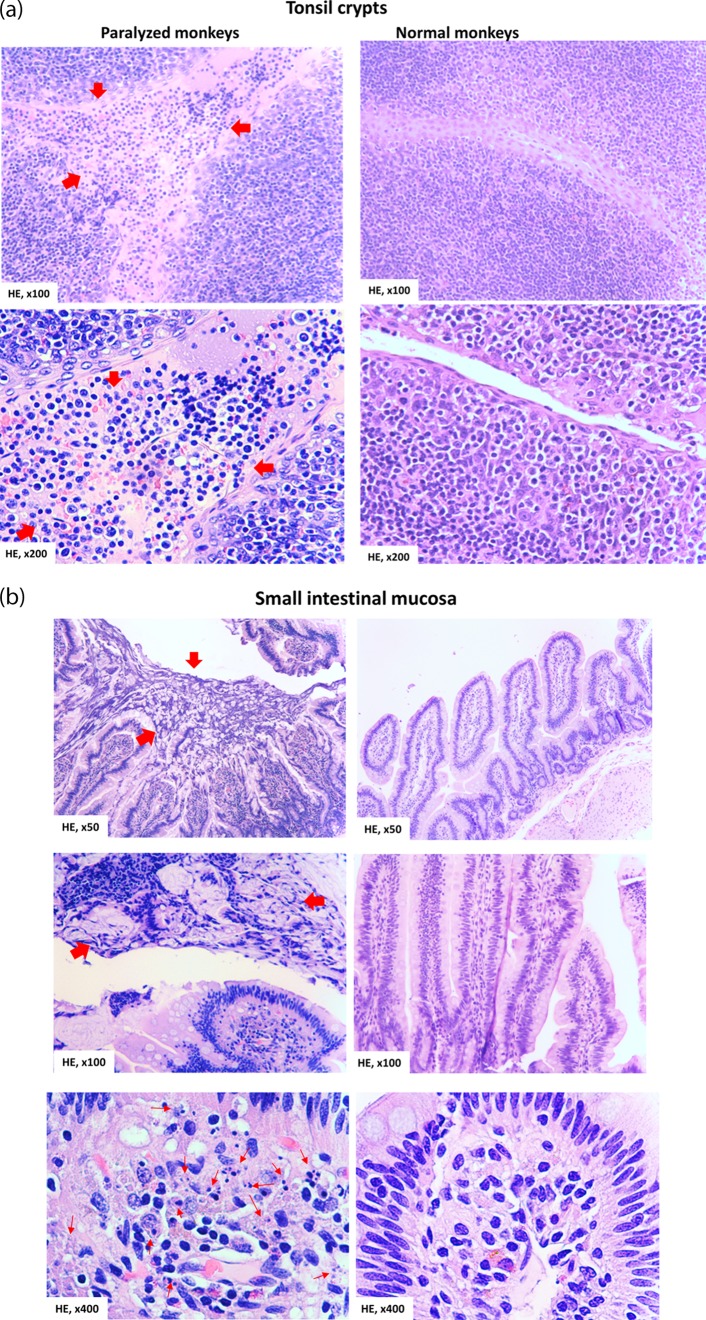

FIG 5.

Poliovirus infection in the tonsil and intestinal mucosa coincided with detectable histopathologic lesions and inflammation. (a) (Top left) Representative image showing the hemorrhage and infiltration of numerous necrotic and inflammatory cells in the stratified squamous epithelia in the tonsil crypt (arrows). (Bottom left) Image showing the destruction and disappearance of the tonsil epithelial covering (red arrows) in the tonsil crypt; the tonsil crypt lumen was filled with hemorrhage and exudates (red arrows) comprised of inflammatory and necrotic cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes. Of note, new or normal epithelia did not emerge underneath the destroyed tissue (under healthy conditions, new epithelia should be seen to outgrow or replace any potential aging or dying cells). (Right) Histology of undamaged tonsil crypts from control macaques not infected with Mahoney poliovirus. Note the intact structures of the stratified squamous epithelia and clean lumen without inflammatory exudates and cells or hemorrhage. (b) (Top left) Large area of necrotic epithelial cells and tissue (arrows) in the surface of the small intestinal mucosa. (Middle left) Necrotic or destroyed epithelial cells/tissue, together with mucus exudates in the gut lumen (arrows). (Bottom left) Infiltration of numerous inflammatory and necrotic cells (arrows) in the lamina propria in small intestine mucosa. (Right) Intact histology of the small intestine mucosa from control macaques not infected with poliovirus Mahoney. The representative tissue sections were collected from macaques 8745 and 8747, who exhibited high-titer poliovirus and viral replication proteins in the tonsil and intestinal mucosae. Similar histopathologic lesions in the tonsil/intestine could be seen in other macaques infected with poliovirus Mahoney.