Abstract

Background

CT-P13 is a biosimilar of Remicade®, an agent approved in some countries for use in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Controlled clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of CT-P13 in rheumatic diseases, but not in IBD.

Aims

To assess the effectiveness and safety of CT-P13 in IBD patients in real clinical practice.

Methods

This is a prospective observational study in patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis treated with CT-P13. The study was performed in one single center. Patients included were naive or switched to anti-TNF treatment from the reference infliximab (Remicade®) to CT-P13. Efficacy and safety were assessed in naive and switched patients who were in remission at the time of the switch at months 3 and 6 of therapy.

Results

87.5 and 83.9% of switched CD patients who were in remission at the time of the switch continued in remission, and 66.7 and 50% of naive CD patients reached remission, at months 3 and 6. In UC switched cases, 92 and 91.3% of patients in remission at the time of the switch continued in remission, at 3 and 6 months. In naive UC patients, the remission rates were 44.4 and 66.7%, at months 3 and 6. Adverse events occurred in 7.5% of patients during 6 months of study.

Conclusions

CT-P13 was efficacious and well tolerated in patients with CD or UC.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, Ulcerative colitis, Biosimilar agent, CT-P13, Infliximab

Introduction

The inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are characterized by chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract and periodic episodes of relapse and remission. Several proinflammatory and immune-regulatory cytokines are upregulated in the mucosa of patients with IBD [1]. Over the past twenty years, the introduction of biological agents has radically improved patients’ outcomes in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including CD and UC [2]. TNF antagonists, such as infliximab, act by blocking TNF binding to its receptor and neutralizing its activity, alleviating mucosal inflammation [3]. In Europe, the anti-TNF agents authorized by the EMA for use in IBD are infliximab [4], adalimumab [5] and golimumab [6]; infliximab and adalimumab are authorized for moderate to severe CD or UC, and golimumab for adult patients with moderately to severely active UC who have not responded adequately to conventional treatments. However, biological agents, including anti-TNF agents, are much more expensive than traditional treatments, and the high cost of biological agents in the treatment of IBD imposes a considerable burden on the national healthcare system [7]. As a result, interest in biosimilars has grown. Biosimilar agents have quality, efficacy and safety similar to those of an already licensed biologic [8], and they have the potential to offer considerable cost savings to the healthcare system [9, 10].

CT-P13 (Remsima® and Inflectra®) is a biosimilar of infliximab (Remicade®), which is its reference medicinal product (RMP). Both CT-P13 and RMP infliximab are chimeric monoclonals IgG1 produced in cell lines derived from the same cell type of murine hybridoma. Both monoclonals have an identical sequence of amino acids and highly comparable higher-order structures [11, 12].

CT-P13 has been evaluated in the treatment of rheumatic diseases in two pivotal clinical trials of rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, respectively. The efficacy and pharmacokinetic equivalence of CT-13 and RMP infliximab have been demonstrated in these two randomized trials, and safety profiles were also comparable for both infliximab formulations [13, 14]. The randomized, phase-IV, double-blind, parallel-group NORSWITCH study [NCT02148640] has been recently communicated [15]. It was developed to analyze interchangeability from originator to biosimilar infliximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, psoriatic arthritis, UC, CD or chronic plaque psoriasis. All adult patients on stable treatment with the originator infliximab for at least 6 months, for any indication, were eligible. This study enrolled 481 patients, from 40 Norwegian study centers. They were randomized to receive treatment and were followed for 52 weeks. Disease worsening occurred in 26.2 and 29.6% of patients in the originator and CTP13 arms, respectively, and the frequency of disease worsening in each specific diagnosis was not different in either of the arms. Similar clinical studies have been initiated in patients with IBD [16, 17] but, so far, no results have been reported, although some studies in clinical practice have been published with good results.

Based on the mentioned clinical studies in rheumatic diseases and on the equivalences in the in vitro activity of CT-P13 and RMP infliximab [11], CT-P13 was authorized by the EMA in 2013 for several indications, including CD and UC [18], and recently by the FDA [19]. It was marketed and made available for the treatment of both IBDs in Spain in February 2015 [20].

Until data of clinical trials in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative disease are available, results in clinical practice may be useful. Here, we show an observational study about the response to CT-P13 and any adverse effects in patients with CD or UC in real clinical practice.

Methods

This is a prospective observational study of effectiveness and safety of patients with moderate to severe CD or UC treated with CT-P13, a biosimilar of infliximab, at the Virgen Macarena Hospital (Seville) from March 2015 to February 2016. Included were anti-TNF naive patients and patients switched from RMP infliximab (Remicade®) to CT-P13. Patients were treated according to the dosage and regime recommended by the Summary of Product Characteristics of Remsima® in Spain [21]. All patients received intravenous corticosteroids and antihistamines as premedication before the infusion treatment.

All patients who were being treated with Remicade® were switched to CT-P13. Patients in whom treatment with CT-13 failed were treated with adalimumab or surgery.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Virgen Macarena Hospital (Seville), and good clinical practice guidelines were followed. Written informed consent was signed by patients.

Montreal classification [22] status was recorded in all patients before enrollment. The efficacy end points were the clinical response in naive patients and the change of response in switched patients, assessed at 3 and 6 months, according to the Harvey-Bradshaw (HB) score [23] for CD patients, and to the Partial Mayo Score [24] for UC patients.

Disease Activity

Clinical response in CD patients was assessed using the following criteria: (1) In switched patients, remission was considered to be maintained when the patient was still in remission after switching, without needing steroids, surgery or increased dose. (2) In naive patients, (a) there was considered to be clinical remission when the Harvey-Bradshaw Score was ≤4; and (b) there was considered to be clinical response when there was an improvement in the Harvey-Bradshaw score, and withdrawal of steroids.

Remission in switched UC patients was considered to be maintained when the patient was still in remission after switching, without needing steroids, surgery or increased dose. In naive patients, remission was assessed when there was a decrease of less than 2 in the Partial Mayo Score, compared to the score before starting CT-P13 therapy.

Also, in the switched patients the HB and the Partial Mayo Score in CD and UC patients, respectively, and the C-reactive protein (CRP) were compared from month 0 to month 3 and to month 6.

Safety

Adverse events (AE) were monitored from the first infusion of CT-P13 until the end of the study and were recorded during the course of the study, according to the Office of Human Research Protection. Suspected adverse reactions were defined as any AE for which there is a reasonable possibility that the drug caused the AE [25].

Statistics

Demographic results and nominal results were reported in percentages and frequencies. Numerical results were reported as average and standard deviation in cases of normal distribution and as median and percentiles (P25; P75) in cases of skewed distribution. The Cochrane’s Q test and the Friedman test were used to analyze the evolution of the clinical scores (HB score) and CRP values of the patients. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated, and the value α = 0.05 was adopted as a level of statistical significance. Analyses were performed using SPSS 22 (IBM Corporation).

Results

A total of 80 CD patients and 40 UC patients were included. The median age of CD patients was 41.2 (SD 12.9) years old, 61.3% (n = 49) were non-smokers, and 52.5% (n = 42) were men. The median age of UC patients was 43.6 (SD 12.5) years old, 85% (n = 34) were non-smokers, and 57.5% (n = 23) were men. Phenotypic characteristics of CD and UC patients, according to the Montreal Classification, are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Phenotypic characteristics of 80 CD patients (Montreal classification [22])

| Characteristic | n (%) | CI (95%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | A1 (<16) | 8/80 (10) | 2.8–17.2 |

| A2 (17–40) | 61/80 (76.3) | 66.3–86.3 | |

| A3 (>40) | 11/80 (13.7) | 5.6–21.9 | |

| Location at diagnosis | L1 (ileal) | 22/80 (27.5) | 17.1–37.9 |

| L2 (colonic) | 32/80 (40) | 28.6–51.4 | |

| L3 (ileocolonic) | 24/80 (30) | 19.3–40.7 | |

| L4 indicator (upper gastrointestinal tract) | 2/80 (2.5) | 0.3–8.7 | |

| Disease behavior | B1 (nonstricturing, nonpenetrating) | 48/80 (60) | 48.6–71.4 |

| B2 (stricturing) | 15/80 (18.7) | 9.6–27.9 | |

| B3 (penetrating) | 17/80 (21.3) | 11.7–30.8 | |

| Perianal disease | Yes | 41/80 (51.3) | 39.7–62.8 |

| No | 39/80 (48.7) | 37.2–60.3 | |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | No | 52/80 (65) | 53.9–76.1 |

Table 2.

Phenotypic characteristics of 40 UC patients (Montreal classification [22])

| Characteristic | n (%) | CI (95%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extent | E1 (proctitis) | 16/40 (40) | 23.6–53.7 |

| E2 (left-sided colitis) | 15/40 (37.5) | 21.2–53.7 | |

| E3 (pancolitis) | 9/40 (22.5) | 8.30–36.7 | |

| Severity | S1 (mild) | 13/40 (32.5) | 16.7-48.3 |

| S2 (moderate) | 20/40 (50) | 33.3–66.7 | |

| S3 (severe) | 7/40 (17.5) | 4.5–30.5 | |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | No | 35/40 (87.5) | 73.2–95.8 |

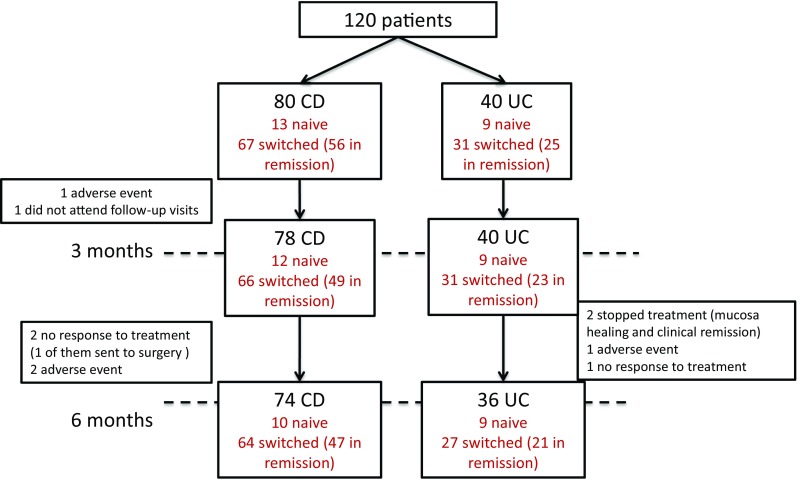

Of the 80 CD patients, 13 (16.25%) were naive to anti-TNF and 67 (83.75%) were switched from RMP infliximab (Remicade®) to CT-P13. 83.5% (56/67) of the switched CD patients were in remission at the time of the switch. Median duration of ongoing Remicade® treatment at the start of the study was 297 (158; 432) weeks. At 3 months, two patients were excluded (one because he did not attend follow-up visits and the other because of an adverse event), and four patients did not continue treatment at month 6 (1 showed no response to treatment, 2 had adverse events, and 1 was sent to surgery).

Of the 40 UC patients, nine (22.5%) were naive to anti-TNF—six had treatment with steroids—and 31 (77.5%) were switched from RMP infliximab (Remicade®) to CT-P13. 80.6% (25/31) of the UC switched patients were in remission at the time of the switch. Median duration of ongoing Remicade® treatment at the start of the study was 203 (42; 294) weeks. At 6 months, four patients had stopped the treatment: two due to clinical and endoscopic remission, one due to no response to treatment and one due to an adverse event (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) included in the study, followed-up at 3 and 6 months. Reason for discontinuation

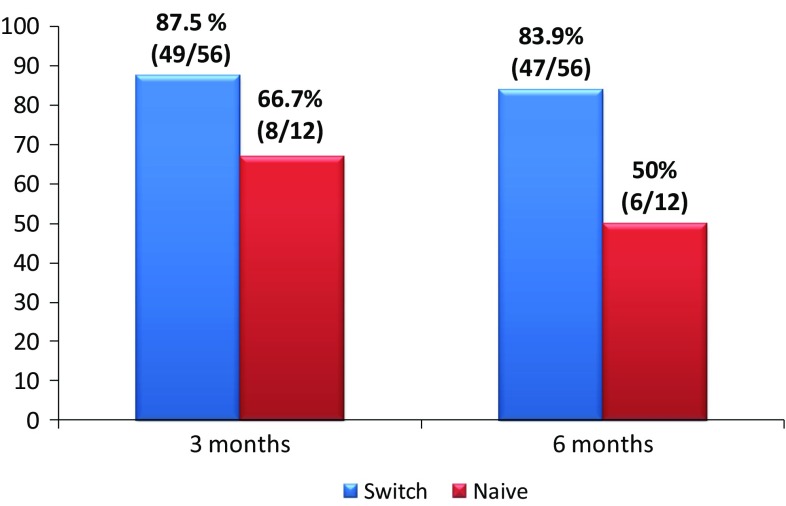

In the CD group of patients, there were available results at 3 months in 78/80 CD patients: 12 naive patients and 66 switched patients. 87.5% (49/56) of switched CD patients in remission maintained remission. 66.7% of CD naive patients reached remission.

There were available results at 6 months in 74 CD patients: 10 naive patients and 64 switched patients. 83.9% (47/56) of switched CD patients in remission maintained remission and 50% of CD naive patients reached remission (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Clinical remission in switched patients who were in remission at the time of switching and in naive patients with Crohn’s disease at 3 and 6 months

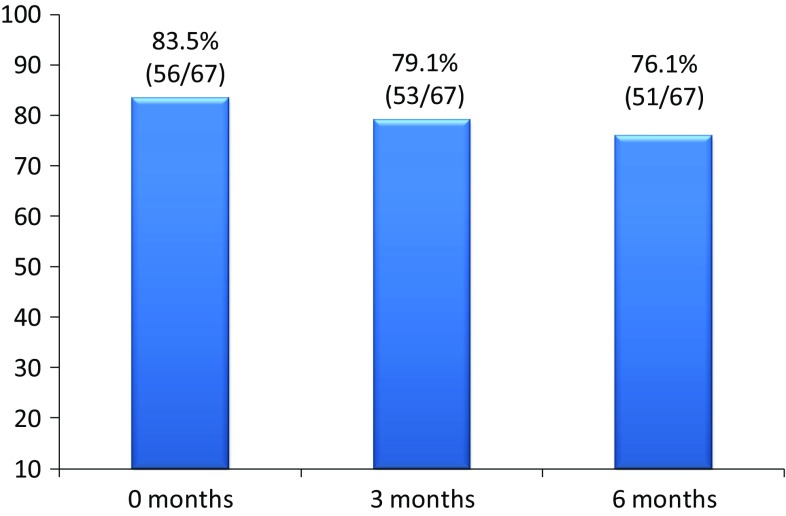

83.5% (56/67) of the switched CD patients were in remission at the time of the switch, 73.1% (49/67) of them at 3 months and 70.1% (47/67) of them at 6 months.

Eleven patients switched from Remicade® to CT-P13 when they were not in remission. In this group, at 3 months, one patient stopped treatment due to a Sweet syndrome and four patients reached remission. At 6 months, these 4 patients in remission continued in remission. Based on these data, globally, at 3 months, 79.1% (53/67) of the switched patients reached remission at 3 months and 76.1% (51/67) were in remission at 6 months (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Global clinical remission in switched CD patients

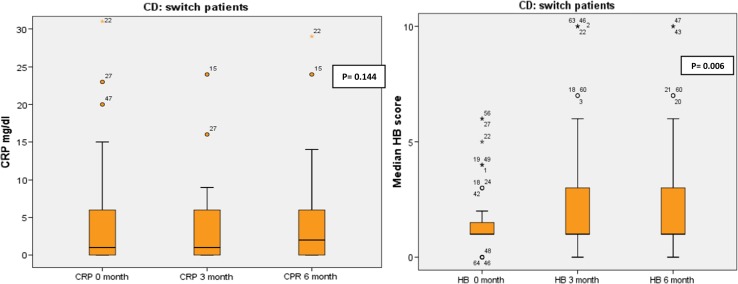

No significant changes in median CRP were observed in switched CD patients in the three periods (CRP: 1 [0; 6] vs 1 [0; 6.3] vs 2 [0; 6.5] at months 0, 3 and 6, respectively; p = 0.144); and the HB score showed a decrease (HB score: 1 [1, 2] vs 1 [1, 3] vs 1 [1, 3] at months 0, 3 and 6, respectively; p = 0.006) (Fig. 4). In de novo patients, the median change in HB score was significant (5.5 [3; 6.7] vs 3 [2, 6] vs 3 [2; 6) at months 0, 3 and 6, respectively; p = 0.05), the reduction was observed between 0 and 3 months (p = 0.0005) and 0 and 6 months (p = 0.005). A reduction in the median of CRP was observed (p = 0.019); the difference was observed between 0 and 6 months (p = 0.03).

Fig. 4.

CRP and HB score in switched patients with Crohn’s disease at 0, 3 and 6 months

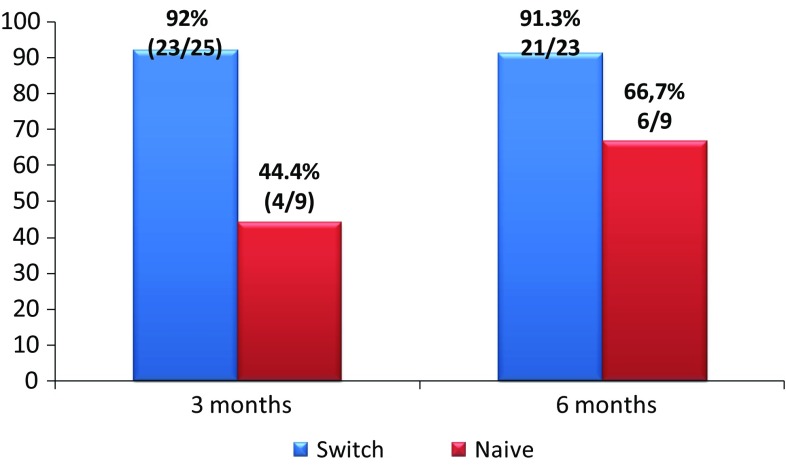

There were available results at 3 months in 40 UC patients. Ninety-two percent (23/25) of switched patients in remission maintained remission. 44.4% (4/9) of naive UC patients reached remission. There were available results at 6 months in 36/40 UC patients: nine naive patients and 27 switched patients. 91.3% (21/23) switched UC patients in remission maintained remission (two of these patients stopped treatment due to clinical remission and mucosa healing), and 66.67% (6/9) of naive UC patients reached remission (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Clinical remission in switched patients who were in remission at the time of switching and in naive patients with ulcerative colitis at 3 and 6 months

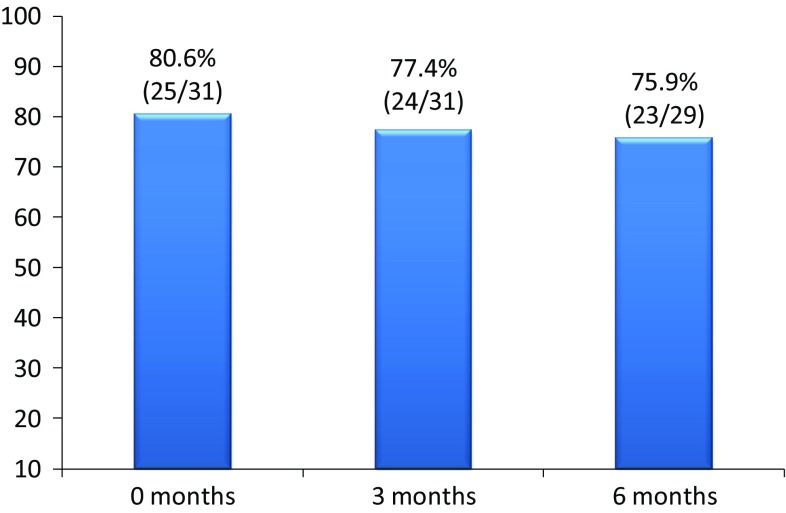

80.6% (25/31) of the switched UC patients were in remission at the time of the switch, 74.2% (23/31) of them at 3 months and 72.4% (21/29) of them at 6 months.

Six UC patients were not in remission at the switch moment. At 3 and 6 months, only one patient reached remission. Based on these data, globally, at 3 months, 77.4% (24/31) of UC switched patients were in remission and at 6 months 75.9% (23/29) (Fig. 6)

Fig. 6.

Global clinical remission in switched UC patients

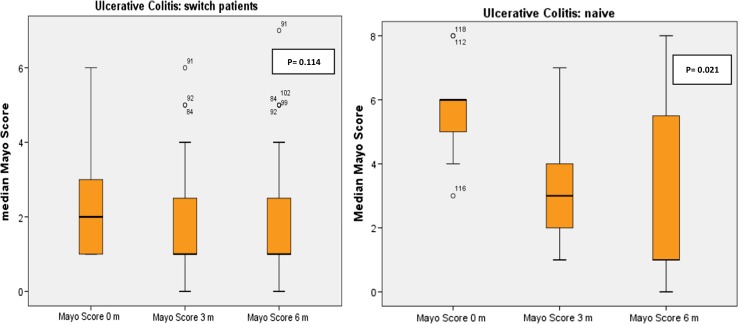

No significant changes in the median of the Modified Mayo Score were observed in switched patients in the three periods: 2 (1; 3) versus 1 (1; 3) versus 1 (0; 9) at months 0, 3 and 6, respectively; p = 0.114. We observed a decrease in the median CRP (2 [1, 10] versus 1 [0; 2] versus 1 [0; 5] at months 0, 3 and 6, respectively; p = 0.04); the reduction was observed between 0 and 3 months (p = 0.04) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Partial Mayo Score in switched and naive patients with ulcerative colitis at 0, 3 and 6 months

In de novo patients, the median change in CRP was not significant (p = 0.135), but the reduction in the Modified Mayo Score reached statistically significant differences (6 [4.5; 7] vs 3 [1.5; 5] vs 1 [1; 5.7] at months 0, 3 and 6, respectively; p = 0.021), the reduction was observed between 0 and 3 months.

Safety

Concerning safety, there were serious adverse events in 9/120 (7.5%) patients: one skin reaction, one abdominal pain, two headaches and two paresthesias during infusion treatment, one Sweet’s Syndrome and two polyarthralgia. In this group, six patients discontinued treatment because of these adverse events. One UC patient discontinued due to paresthesias during the infusion treatment.

Discussion

Clinical trials are going to evaluate the efficacy and safety of CT-P13 in CD and UC patients [15–17], but until these data are available, outcomes obtained in clinical practice about the use of this TNF antagonist biosimilar can be useful for clinicians. These preliminary results of 6 months of follow-up in 120 IBD patients treated with CT-P13 indicate its effectiveness and safety. Response was maintained in 84% of switched CD and in 91.3% of switched UC patients, and clinical remission was reached in 50% of naive CD and 70% of naive UC patients. Nevertheless, it is necessary to continue assessing the response in these patients over a longer period.

All observational postmarketing studies published to date have reported positive outcomes for response/remission in CD and UC patients treated with CT-P13, regardless of whether patients had received a prior anti-TNF or not [26–29]. These findings are consistent with those of randomized controlled trials made in rheumatic diseases, comparing CT-P13 and RMP infliximab [13, 14].

Jahnsen et al. studied a total of 78 IBD patients and reported a significant improvement—in the Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI)—in a series of 46 Crohn’s disease patients (p = 0.01) treated with CT-P13 who had been treated previously with a TNF antagonist [26]—the number of switched UC patients was too small to make statistical calculations. Jung et al. studied a total of 59 IBD patients: 32 anti-TNF naive patients with CD and 27 patients with CD switched from infliximab to CT-P13, and 42 anti-TNF naive patients with UC and nine patients with UC switched from infliximab to CT-P13. They observed clinical response in 87.5% and remission in 75% of anti-TNF naive patients with CD, at week 54, and clinical response in 100% and remission in 50% of anti-TNF naive patients with UC, at week 54. In patients switched from infliximab to CT-P13 they found that 92.6% of CD patients and 66.7% of UC patients maintained a similar efficacy compared with infliximab [27]. Smits et al. [30] studied a cohort of 83 Remicade®-treated IBD patients who were switched to CT-P13. They found that IBD activity remained stable after switching and that over 80% of patients maintained clinical remission.

In the current study, adverse events were detected in 9 of the 120 IBD patients followed-up during 6 months, that is, a rate of 11.2%. According to published reports, no unexpected TEAEs were observed—considering potential TEAEs of RMP infliximab— in CD and UC patients treated to date with CT-P13 [26, 27, 29–31]. A Korean study in 95 CD patients and 78 UC patients reported that treatment-related TEAEs occurred in 10% of patients, mostly mild-moderate in severity; and there were five serious TEAEs (one abdominal pain, two infusion-related reactions and two infections) [31]. In their study, Smits et al. [30] found two patients who developed new detectable antidrug antibodies (ADAs), but, owing to technical limitations, they could not exclude the possibility that these ADAs were in fact preexisting at baseline.

Reasons for validating and extrapolating immunogenicity data across indications [32, 33] plus authorization of CT-P13 by the EMA in 2013 [18], together with financial reasons, have favored its use in CD and UC patients. Results from this study and others in clinical practice using CT-P13 in CD and UC patients show that this biosimilar is an effective and well-tolerated treatment in these patients [26–31]. The current study and the mentioned experiences reported in clinical practice with CT-P13 in CD and UC patients will be supported by the results of clinical trials now been performed. Access to highly effective biological drugs will widen to more patients who will be able to receive effective therapy earlier.

This is a preliminary study which does not provide data on long-term maintenance of CT-P13, but it demonstrated effectiveness and safety at 3 and 6 months, and support to continue long-term therapy studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ana Moreno Cerro on behalf of Springer Healthcare Communications, who provided medical writing assistance.

Funding

Medical writing support was funded by Kern Pharma.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

F Argüelles-Arias has participated in advisory boards and has received financial support to attend scientific meetings from Kern Pharma. MF Guerra Veloz, R Perea Amarillo, A Vilches-Arenas, L Castro Laria, B Maldonado Pérez, D Chaaro and A Benítez Roldán have received financial support to attend scientific meetings from Kern Pharma. V Merino, G Ramírez, A Caunedo Álvarez and M Romero Gómez have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10620-017-4657-0.

Contributor Information

F. Argüelles-Arias, Email: farguelles@telefonica.net

M. F. Guerra Veloz, Email: maferguerrita@hotmail.com

R. Perea Amarillo, Email: repadue@gmail.com

A. Vilches-Arenas, Email: ava@us.es

L. Castro Laria, Email: luisacastro@ono.com

B. Maldonado Pérez, Email: bmalpe@hotmail.com

D. Chaaro, Email: d.chaaro@gmail.com

A. Benítez Roldán, Email: benisalu6@hotmail.com

V. Merino, Email: vicente.merino.sspa@juntadeandalucia.es

G. Ramírez, Email: gabriel.ramirez.sspa@juntadeandalucia.es

A. Caunedo Álvarez, Email: acaunedoa@gmail.com

M. Romero Gómez, Email: mromerogomez@us.es

References

- 1.Papadakis KA, Targan SR. Role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:289–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Côté-Daigneault J, Bouin M, Lahaie R, Colombel J-F, Poitras P. Biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: what are the data? U Eur Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:419–428. doi: 10.1177/2050640615590302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tracey D, Klareskog L, Sasso EH, Salfeld JG, Tak PP. Tumor necrosis factor antagonist mechanisms of action: a comprehensive review. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;117:244–279. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Medicines Agency—European public assessment reports—Infliximab. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/landing/epar_search.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124&source=homeMedSearch&keyword=infliximab&category=human&isNewQuery=true.

- 5.European Medicines Agency—European public assessment reports—Adalimumab. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/landing/epar_search.jsp&mid=%0AWC0b01ac058001d124&source=homeMedSearch&keyword=adalimumab&category=human&isNewQuery=true.

- 6.European Medicines Agency—European public assessment reports—Simponi (golimumab). http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/000992/human_med_001053.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124.

- 7.Bodger K, Kikuchi T, Hughes D. Cost-effectiveness of biological therapy for Crohn’s disease: Markov cohort analyses incorporating United Kingdom patient-level cost data. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:265–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Expert Committee on biological standarization. Geneva, 19–23 Oct 2009. Guidelines on evaluation of similar biotherapeutic products (SBPs). http://www.who.int/biologicals/areas/biological_therapeutics/BIOTHERAPEUTICS_FOR_WEB_22APRIL2010.pdf.

- 9.Haustein R, de Millas C, Höer A, Häyssker B. Saving money in the European healthcare systems with biosimilars. GaBI J. 2012;1:120–126. doi: 10.5639/gabij.2012.0103-4.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim J, An Hong J, Kudrin A. P137 5 year budget impact analysis of CT-P13 (Infliximab) for the treatment of Crohn’s disease in UK, Italy and France. https://www.ecco-ibd.eu/index.php/publications/congress-abstract-s/abstracts-2015/item/p137-5-year-budget-impact-analysis-of-ct-p13-infliximab-for-the-treatment-of-crohnaposs-disease-in-uk-italy-and-france.html.

- 11.European Medicines Agency. Committee for medicinal products for human use (CHMP). Assessment report: Remsima (infliximab). 2013. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/002576/WC500151486.pdf.

- 12.Jung SK, Lee KH, Jeon JW, et al. Physicochemical characterization of Remsima®. MAbs. 2014;6:1163–1177. doi: 10.4161/mabs.32221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoo DH, Hrycaj P, Miranda P, et al. A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study to demonstrate equivalence in efficacy and safety of CT-P13 compared with innovator infliximab when coadministered with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: the PLANETRA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1613–1620. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park W, Hrycaj P, Jeka S, et al. A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, parallel-group, prospective study comparing the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of CT-P13 and innovator infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: the PLANETAS study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1605–1612. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goll GL, Olsen IC, Jorgensen KK, et al. Biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) is not inferior to originator infliximab: results from a 52-week randomized switch trial in Norway. 2016 ACR/ARHP annual meeting. Abstract 19L. http://acrabstracts.org/abstract/biosimilar-infliximab-ct-p13-is-not-inferior-to-originator-infliximab-results-from-a-52-week-randomized-switch-trial-in-norway/.

- 16.Demonstrate Noninferiority in Efficacy and to Assess Safety of CT-P13 in Patients With Active Crohn’s Disease—Full Text View—ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02096861.

- 17.To Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Remsima™ in Patients With Crohn’s Disease (CD) or Ulcerative Colitis (UC)—Full Text View—ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02326155.

- 18.EPAR summary for the public. Remsima, INN-infliximab. 2013. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Summary_for_the_public/human/002576/WC500150872.pdf.

- 19.Clinical Addendum PREA. Biosimilar CT-P13. Food and Drug Administration. 2016. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/UCM510208.pdf.

- 20.Kern Pharma Biologics lanza su primer biosimilar en España: Remsima. 2015. http://www.pmfarma.es/noticias/20238-kern-pharma-biologics-lanza-su-primer-biosimilar-en-espana-remsima.html.

- 21.Ficha técnica de Remsima, INN—infliximab. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/es_ES/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002576/WC500150871.pdf.

- 22.Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a working party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19:5–36. doi: 10.1155/2005/269076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Best WR. Predicting the Crohn’s disease activity index from the Harvey-Bradshaw Index. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:304–310. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000215091.77492.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dignass A, Eliakim R, Magro F, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 1: definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:965–990. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unanticipated Problems Involving Risks & Adverse Events Guidance (2007). HHS.gov. Office for Human Research Protections. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/reviewing-unanticipated-problems/index.html.

- 26.Jahnsen J, Detlie TE, Vatn S, Ricanek P. Biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a Norwegian observational study. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:45–52. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1091308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung YS, Park DI, Kim YH, et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13, a biosimilar of infliximab, in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a retrospective multicenter study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1705–1712. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farkas K, Rutka M, Bálint A, et al. Efficacy of the new infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 induction therapy in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis—experiences from a single center. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15:1257–1262. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2015.1064893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keil R, Wasserbauer M, Zádorová Z, et al. Clinical monitoring: infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 in the treatment of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:1062–1068. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2016.1149883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smits LJT, Derikx LAAP, de Jong DJ, et al. Clinical outcomes following a switch from Remicade® to the biosimilar CT-P13 in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a prospective observational Cohort study. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:1287–1293. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park SH, Kim Y-H, Lee JH, et al. Post-marketing study of biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) to evaluate its safety and efficacy in Korea. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:35–44. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1091309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reinisch W, Louis E, Danese S. The scientific and regulatory rationale for indication extrapolation: a case study based on the infliximab biosimilar CT-P13. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:17–26. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1091306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ben-Horin S, Heap GA, Ahmad T, et al. The immunogenicity of biosimilar infliximab: can we extrapolate the data across indications? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:27–34. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1091307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]