Abstract

The bile acid-activated receptors, nuclear farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and the membrane Takeda G-protein receptor 5 (TGR5), are known to improve glucose and insulin sensitivity in obese and diabetic mice. However, the metabolic roles of these two receptors and the underlying mechanisms are incompletely understood. Here, we studied the effects of the dual FXR and TGR5 agonist INT-767 on hepatic bile acid synthesis and intestinal secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in wild-type, Fxr−/−, and Tgr5−/− mice. INT-767 efficaciously stimulated intracellular Ca2+ levels, cAMP activity, and GLP-1 secretion and improved glucose and lipid metabolism more than did the FXR-selective obeticholic acid and TGR5-selective INT-777 agonists. Interestingly, INT-767 reduced expression of the genes in the classic bile acid synthesis pathway but induced those in the alternative pathway, which is consistent with decreased taurocholic acid and increased tauromuricholic acids in bile. Furthermore, FXR activation induced expression of FXR target genes, including fibroblast growth factor 15, and unexpectedly Tgr5 and prohormone convertase 1/3 gene expression in the ileum. We identified an FXR-responsive element on the Tgr5 gene promoter. Fxr−/− and Tgr5−/− mice exhibited reduced GLP-1 secretion, which was stimulated by INT-767 in the Tgr5−/− mice but not in the Fxr−/− mice. Our findings uncovered a novel mechanism in which INT-767 activation of FXR induces Tgr5 gene expression and increases Ca2+ levels and cAMP activity to stimulate GLP-1 secretion and improve hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Activation of both FXR and TGR5 may therefore represent an effective therapy for managing hepatic steatosis, obesity, and diabetes.

Keywords: bile acid, lipid metabolism, liver metabolism, obesity, type 2 diabetes, FXR, GLP-1, TGR5, bile acid metabolism, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Introduction

Bile acids are known to regulate lipid, glucose, and energy homeostasis through activation of FXR2 and TGR5 (Takeda G-protein receptor 5 (also known as Gpbar-1 for G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor-1)) (1, 2). Bile acid synthesis in the liver generates two primary bile acids, cholic acid (CA) and chenodeoxycholic (CDCA), in humans (3). However, in mouse liver, CDCA is converted to α- and β-muricholic acids (α/β-MCAs) due to the expression of a unique Cyp2c70 enzyme in mouse but not in human liver (4). Cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) is the first and rate-limiting enzyme in the classic bile acid synthesis pathway, whereas sterol 12α-hydroxylase (CYP8B1) catalyzes CA synthesis. The alternative bile acid synthesis pathway is initiated by steroid 27-hydroxylase (CYP27A1), followed by oxysterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7B1) to produce mainly CDCA. The relative contributions of these two pathways to total bile acid synthesis determines bile acid composition and hydrophobicity of the bile acid pool. Bile acids are conjugated to glycine or taurine for secretion into gallbladder bile. In the ileum, bile acids are reabsorbed, and gut bacterial bile salt hydrolases de-conjugate bile acids, whereas 7α-dehydroxylase converts CA and CDCA to deoxycholic acid (DCA) and lithocholic acid (LCA), respectively (2). CA (EC50 = 586 μm) and CDCA (EC50 = 17 μm) are the endogenous ligands of FXR, whereas T-LCA (EC50 = 0.03 μm) and DCA (EC50 = 1.01 μm) are more effective in activating TGR5 (5, 6). Enterohepatic circulation of bile acids from the intestine to the liver activates FXR, which induces a small heterodimer partner (SHP) to inhibit transcription of the Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1 genes and ultimately bile acid synthesis. In the intestine, FXR induces fibroblast growth factor 15 (FGF15), which activates hepatic FGF receptor 4 signaling to further inhibit Cyp7a1 gene transcription (7).

Activation of FXR is thought to be beneficial in improving insulin and glucose sensitivity in diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (2, 8–10). Paradoxically, deficiency or antagonism of intestine FXR was shown to improve obesity, insulin resistance, and NAFLD (11, 12), but activation of intestinal FXR also improves metabolic disease in diabetic mice (13). Thus, the role and mechanism of FXR in the regulation of lipid and glucose metabolism and NAFLD are controversial and not completely understood.

The role of TGR5 in the regulation of hepatic bile acid metabolism has not been explored. TGR5 is widely expressed in many tissues, including intestine, gallbladder, liver (Kupffer cells, not hepatocytes), and brain (5, 6, 14). In the gastrointestinal tract, activation of TGR5 by bile acids and synthetic agonists protects intestinal barrier function, reduces inflammation, and stimulates gallbladder filling and GLP-1 secretion from enteroendocrine L cells (15, 16). GLP-1 is an intestinal incretin produced in L cells through processing of pre-proglucagon by prohormone convertase 1/3 (PC1/3) and is released in response to meal intake (17). GLP-1 stimulates insulin synthesis, increases postprandial insulin secretion from pancreatic β cells, and improves insulin resistance (18). GLP-1 secretion is stimulated by nutrients in the intestinal lumen, such as carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and bile acids (15, 19). Activation of TGR5 increases intracellular cAMP to stimulate cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA), which activates cAMP-response element-binding protein and induces thyroid hormone deiodinase 2 to stimulate energy metabolism in brown adipose tissues, and to alleviate obesity and hepatic steatosis in diet-induced obese mice (20, 21). TGR5 is not expressed in hepatocytes, and its role in the regulation of hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism is not understood. Recently, TGR5 was reported to play a key role in regulation of bile acid synthesis and fasting-induced hepatic steatosis in mice (22).

Drugs targeting FXR and TGR5 were developed recently to treat cholestasis and NAFLD (2). The FXR-selective agonist obeticholic acid (OCA,INT-747; 6α,ethyl-3α,7α-dihydroxy-5β-cholan-24-oic acid; EC50 = 0.099 μm) was approved to treat primary biliary cholangitis patients and is in clinical trials for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (23, 24). INT-767 (6α-ethyl-3α,7α,23(S)-trihydroxy-24-nor-5β-cholan-23-sulfate sodium salt) is a dual FXR and TGR5 agonist (EC50FXR = 0.03 μm; EC50TGR5 = 0.63 μm) (25) and has been shown to improve NAFLD and diabetes in diabetic mice and Ldlr−/−/Apoe−/− mice (25–27). The TGR5-selective agonist INT-777 (6α-ethyl-23(S)-methyl-3α,7α,12α-trihydroxy-5β-cholan-24-oic acid; EC50 = 0.82 μm) stimulates GLP-1 secretion and improves glucose homeostasis (20). However, the role of INT767 in regulation of bile acid synthesis and the underlying mechanism in anti-diabetes and obesity remain unclear and require further study.

In this study, INT-767, OCA, and INT-777 were orally administered to mice to study their effects on hepatic bile acid synthesis, glucose and lipid metabolism, and intestinal GLP-1 secretion in wild-type, Fxr−/−, and Tgr5−/− mice. The data suggest that the dual FXR and TGR5 agonist INT-767 was highly efficacious in activating intestinal FXR, inducing TGR5 gene expression, and stimulating cellular Ca2+ concentration and GLP-1 secretion to improve glucose and insulin tolerance and lipid metabolism. INT-767 treatment reduced body weight and improved hepatic bile acid, lipid, and glucose metabolism and increased insulin sensitivity in high fat diet-induced obese mice. INT-767 has great therapeutic potential for treating NAFLD, diabetes, and obesity.

Results

Differential effects of INT-767, OCA, and INT-777 on hepatic bile acid, glucose, and lipid metabolism

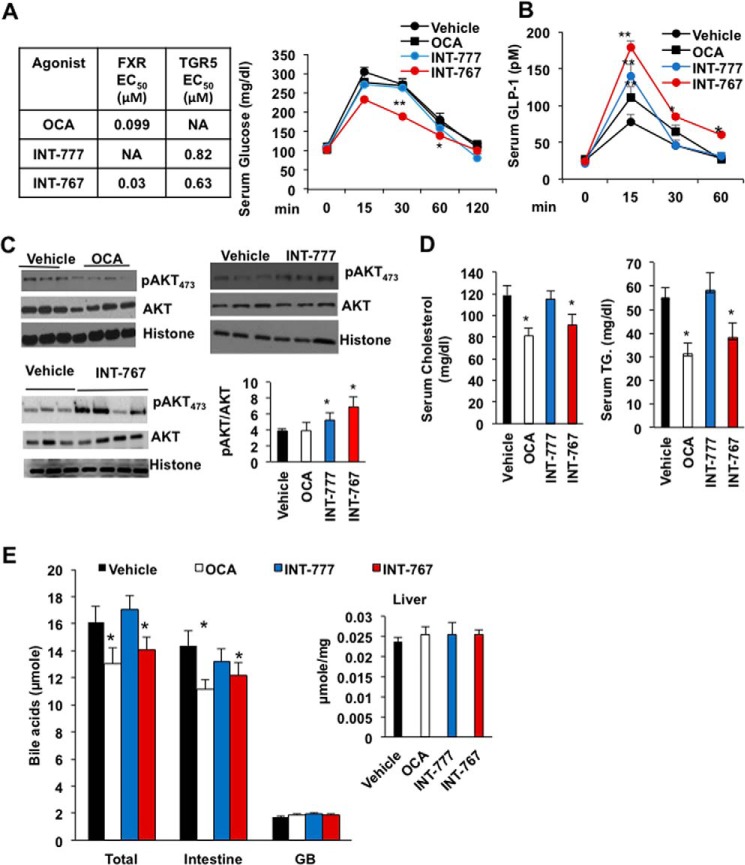

Oral gavage of 30 mg/kg FXR-selective agonist OCA, TGR5-selective agonist INT-777, and dual FXR and TGR5 agonist INT-767 to wild-type C57BL6J mice was carried out to study their effects on intestinal GLP-1 secretion and liver metabolism. Results show that the INT-767 significantly improved glucose tolerance, whereas OCA and INT-777 did not (Fig. 1A). INT-767 and INT-777 rapidly stimulated glucose-induced GLP-1 secretion peaking at 15 min post-administration, whereas the effect of OCA was weaker (Fig. 1B). INT-767 and INT-777, but not OCA, significantly increased AKT473 phosphorylation indicating increased hepatic insulin signaling (Fig. 1C). OCA and INT-767, but not INT-777, significantly reduced serum cholesterol and triglycerides in wild-type mice (Fig. 1D). OCA and INT-767, but not INT-777, significantly reduced total bile acid pool size (intestine, liver, and gallbladder) by reducing intestinal bile acid contents (Fig. 1E). Among the three agonists tested, INT-767 is most effective in stimulating GLP-1 secretion, improving serum lipid profile, and stimulating glucose and insulin sensitivity. Although OCA increased serum GLP-1 and reduced serum lipids, it did not significantly increase glucose tolerance or hepatic insulin signaling.

Figure 1.

INT-767 stimulates glucose and hepatic insulin signaling in mice. Wild-type C57BL/6J mice were orally gavaged with the dual FXR and TGR5 agonist INT-767 (30 mg/kg, n = 10), FXR agonist OCA (30 mg/kg, n = 10), TGR5 agonist INT-777 (30 mg/kg, n = 8), or vehicle (5% CMC in water or 0.2% DMSO, n = 15) as described under “Experimental procedures.” A, efficacy of FXR-selective agonist OCA, TGR5-selective agonist INT-777, and dual FXR and TGR5 agonist INT-767, and effects of these agonists on oral glucose tolerance test in wild-type mice. B, serum GLP-1 assay of wild-type mice. C, AKT phosphorylation assay of liver lysates from ligand-treated wild-type mice. Each lane represents lysates from single mouse liver. D, OCA and INT-767 reduced serum cholesterol and triglyceride level. E, OCA and INT-767 reduced bile acid pool size. Intestine, liver, and gallbladder were isolated from mice (n = 8) treated with FXR agonists (30 mg/kg), and bile acid contents were assayed. The total bile acid pool includes bile acids in the intestine, liver, and gallbladder. Results were expressed as means ± S.E. * indicates statistically significant difference of treated versus vehicle control, p ≤ 0.05, and ** indicates p ≤ 0.01. Student's t test was used for statistical analysis.

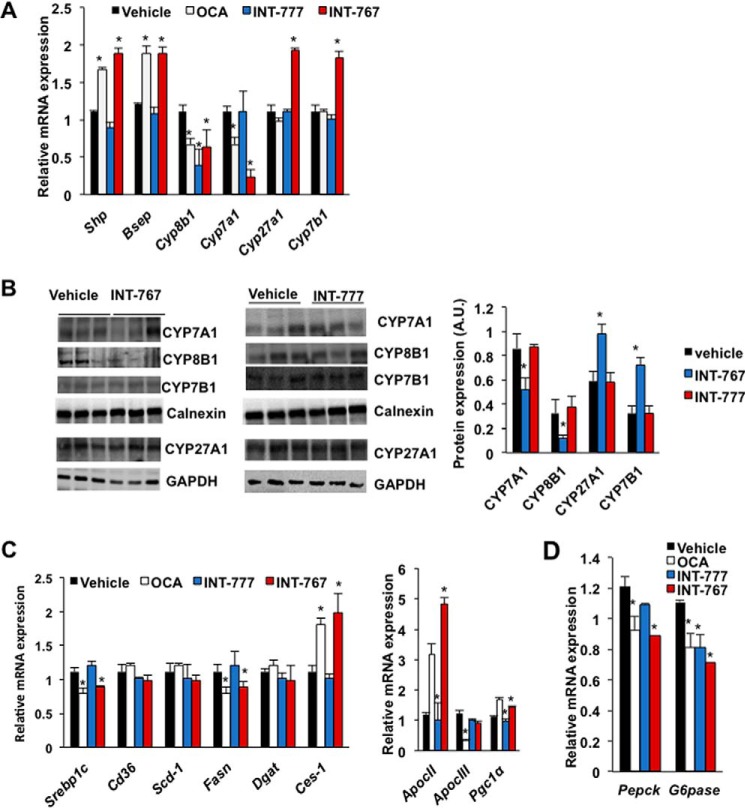

OCA is known to inhibit bile acid synthesis and decrease the bile acid pool (28). INT-777 did not affect bile acid synthesis and pool size (22), whereas the effect of INT-767 on bile acid synthesis has not been studied. Fig. 2A shows that OCA and INT-767, but not INT-777, significantly reduced liver mRNAs encoding Cyp7a1 in the classic bile acid synthesis pathway. All three agonists reduced mRNA for Cyp8b1 involved in cholic acid synthesis. Interestingly, only INT-767 significantly increased mRNA for Cyp7b1 in the alternative bile acid synthesis pathway and for mitochondrial Cyp27a1, which initiates the alternative pathway. OCA and INT-767 increased mRNA levels of Shp and the canalicular bile salt expert pump (Bsep) indicating activation of FXR signaling in hepatocytes (Fig. 2A). Immunoblotting analysis shows that INT-767, but not INT-777, significantly reduced CYP7A1 and CYP8B1 protein expression but increased CYP7B1 and CYP27A1 protein expression (Fig. 2B), consistent with their effects on mRNA expression levels (Fig. 2A). INT-767 and OCA, but not INT-777, reduced steroid-response element-binding protein-1c (Srebp1c) and fatty-acid synthase (Fasn), but not diacylglycerol acetyltransferase (Dgat) involved in lipogenesis, and induced carboxylesterase-1 (Ces-1) involved in triglyceride hydrolysis (Fig. 2C). OCA significantly induced mRNA for hepatic apolipoprotein CII (ApoCII), an activator of lipoprotein lipase and peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor γ-coactivator-1α (Pgc1α) in energy metabolism, but reduced ApoCIII, an inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase. INT767 strongly induced ApoCII mRNA expression. These agonists also reduced mRNA expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (Pepck) and glucose-6-phosphatase (G6pase) involved in gluconeogenesis (Fig. 2D). Overall, these results indicate that INT-767 is more effective than OCA in regulation of bile acid synthesis by inhibiting the classic pathway and stimulating the alternative pathway for bile acid synthesis to improve hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism via activation of hepatic FXR signaling and inhibition of lipogenesis and increasing lipoprotein metabolism.

Figure 2.

Differential effects of FXR and TGR5 agonists on key genes involved in hepatic bile acid, lipid metabolism, and gluconeogenesis. Wild-type C57BL/6J mice were orally gavaged with INT-767 (30 mg/kg, n = 10), OCA (30 mg/kg, n = 10), INT-777 (30 mg/kg, n = 8), or vehicle (5% CMC in water, n = 10) as described under “Experimental procedures.” A, real-time PCR analysis of mRNA expression of genes in bile acid synthesis (Cyp7a1, Cyp8b1, Cyp7b1, and Cyp27a1), transport (Bsep), and regulation (Shp). B, immunoblotting analysis of CYP7A1, CYP8B1, and CYP7B1 proteins in mouse liver microsomes and CYP27A1 protein in whole-liver lysate of mice treated with INT-767 or INT-777. Each lane represents protein from a single mouse. C, qPCR analysis of relative mRNA expression levels of key genes in lipogenesis (Srebp-1c and Fasn) and triglyceride metabolism (CD36, Scd-1, Dgat, and Ces-1). D, qPCR analysis of relative mRNA expression levels from key gluconeogenic genes (Pepck and G6pase). Relative mRNA expression levels were normalized to Gaphd mRNA. The results were expressed as means ± S.E. * indicates statistically significant difference, treated versus vehicle control, p ≤ 0.05. Student's t test was used for analysis.

INT-767 altered bile acid synthesis

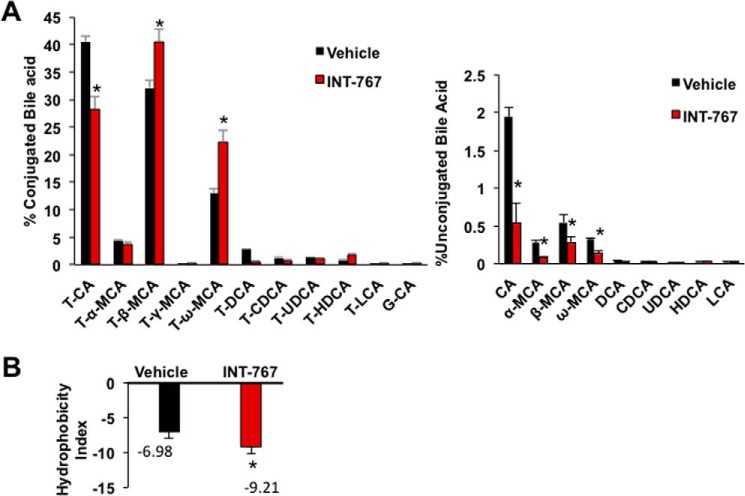

Effects of OCA and INT-777, but not INT-767, on bile acid composition have been reported (22, 28). Analysis of gallbladder bile acid composition, which represents newly synthesized bile acids and bile acid recirculation to the liver from intestine, shows that INT-767 decreased TCA and CA, increased T-β-MCA and T-ω-MCA, but had no effect on T-LCA and LCA contents in gallbladder bile (Fig. 3A). T-β-MCA is a primary bile acid synthesized in mouse liver, and T-ω-MCA is a secondary bile acid produced by the gut microbiota. INT-767 reduced unconjugated bile acids and increased tauro-conjugated bile acids in gallbladder bile. Increasing T-MCA and decreasing of TCA by INT-767 reduced hydrophobicity of bile (Fig. 3B). Effect of INT-767 on bile acid composition is consistent with changes of bile acid synthesis gene expression (Fig. 2, A and B) and indicates switching of bile acid synthesis from the classic to the alternative pathway.

Figure 3.

Gallbladder bile acid composition and hydrophobicity of mice treated with INT-767. Wild-type C57BL/6J mice were orally gavaged with INT-767 (30 mg/kg, n = 7) or vehicle (0.5% CMC in water, n = 7) as described under “Experimental procedures.” Gallbladders were isolated, and bile acid content was measured using 2 μl of bile. A, gallbladder bile acids composition in INT-767-treated mice. Percent bile acids were calculated with respect to total gallbladder bile acids (μm) by HPLC-MS. B, hydrophobicity index of gallbladder bile calculated using formula hydrophobicity index of individual bile acid × (mm) concentration of individual bile acid in the gallbladder. Hydrophobicity index used: TCA = 0; T-α-MCA = −0.84; TβMCA = −0.78; T-HDCA = −0.37; T-γMCA and T-ωMCA = −0.33; T-UDCA = −0.27; T-CDCA = 0.46; T-DCA = 0.59; and T-LCA = 1. Results were expressed as means ± S.E. * indicates statistically significant difference between treated versus vehicle control, p ≤ 0.05. Student's t test was used for analysis.

Fxr induces Tgr5 gene expression in mouse intestine

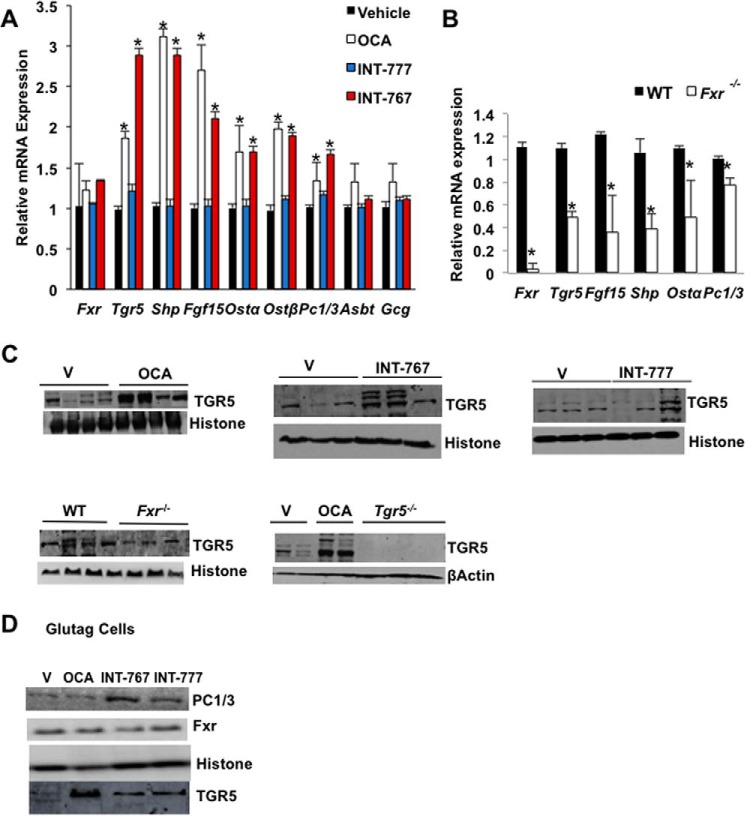

Fig. 4A shows that OCA and INT-767 significantly induced FXR target gene mRNA levels in the ileum, including Shp, Fgf15, organic solute transporter 1α (Ostα), and Ostβ mRNA levels, whereas the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (Asbt) mRNA expression was not affected. Surprisingly, OCA and INT-767 strongly induced Tgr5 mRNA expression. Interestingly, these FXR agonists also induced prohormone convertase 1/3 (PC1/3), which processes pre-proglucagon to GLP-1 in L cells. These data provide the first evidence that FXR might induce intestinal Tgr5 and Pc1/3 gene expression to stimulate GLP-1 processing and secretion. However, these FXR agonists did not affect pro-glucagon (Gcg) mRNA expression in mouse ileum, in contrast to a previous report that the FXR-selective agonist GW4064 inhibited Gcg expression (29). Consistently, intestinal Fgf15, Shp, Ostα, Tgr5, and Pc1/3 mRNA levels were all reduced in the ileum of Fxr−/− mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 4B). Immunoblotting analysis showed that TGR5 protein levels were induced in the ileum of OCA or INT767-treated wild-type mice but were reduced in Fxr−/− mice and absent in the intestine of Tgr5−/− mice (Fig. 4C). OCA and INT767 significantly increased PC1/3 protein expression in Glutag cells (Fig. 4D). Overall, these results suggest that activation of FXR induced Pc1/3 and Tgr5 mRNA and protein expression to increase processing of pre-proglucagon to GLP-1 for secretion.

Figure 4.

INT-767 induces TGR5 and FXR target genes in mouse ileum and Glutag cells. Wild-type C57BL/6J mice were orally gavaged with INT-767 (30 mg/kg, n = 10), OCA (30 mg/kg, n = 10), INT-777 (30 mg/kg, n = 8), or vehicle (0.5% CMC, n = 10) as described under “Experimental procedures.” A, qPCR analysis of ileum FXR target gene expression in wild-type mice. * indicates statistically significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) of treated versus vehicle control. B, relative mRNA expression of FXR target genes in the distal ileum of Fxr−/− (n = 8) and wild-type (n = 8) mice. Results were expressed as means ± S.E. * indicates statistically significant difference of Fxr−/− versus wild-type mice. Student's t test was used for analysis (p ≤ 0.05). C, immunoblotting analysis of TGR5 protein in distal ileum of OCA, INT-767, INT-777, or vehicle (V)-treated wild-mice, or Fxr−/− mice and Tgr5−/− mice as indicated. D, immunoblotting analysis of FXR and PC1/3 protein expression in Glutag cells treated with 10 μm each of OCA, INT-767, or INT-777 for 12 h in media containing 5 mm glucose.

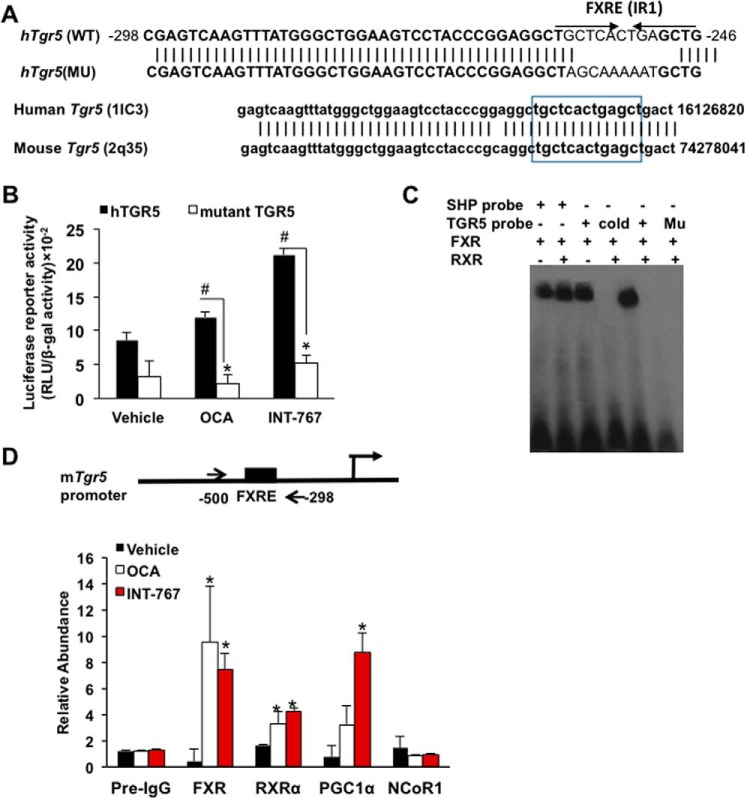

TGR5 promoter has a functional FXR-responsive element

To study the mechanism of FXR induction of TGR5 expression, an inverted repeat with one-nucleotide spacing (IR1) was identified on the proximal promoter of the human TGR5 gene, which is highly conserved in the mouse Tgr5 gene (lower panel, Fig. 5A). To test whether this putative FXRE is functional, a human TGR5 promoter (nt −500 to −298)/luciferase reporter was constructed for use in transient transfection assays in STC-1 cells. INT-767 significantly stimulated human TGR5 promoter/luciferase reporter activity (Fig. 5B). Mutation of the IR1 sequence decreased basal reporter activity, which was not stimulated by OCA or INT-767. These data suggest that this FXRE in the human TGR5 promoter is functional and responsive to stimulation by INT-767. An electrophoretic mobility shift assay revealed that in vitro transcribed and translated FXR and FXR/RXRα heterodimer retarded the mobility of a labeled TGR5 probe containing the FXRE or the SHP probe used as a positive control (Fig. 5C). Addition of unlabeled TGR5 probe (cold) or mutant TGR5 probe abolished the band shift. These results indicate that the IR1 site on the human and mouse Tgr5 promoter binds FXR/RXRα. Furthermore, nuclei were isolated from ileum of mice treated with OCA or INT-767 for chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP). The ChIP assay showed that OCA and INT-767 strongly increased FXR and RXRα occupancy on the mouse Tgr5 promoter containing the FXRE compared with the vehicle-treated and non-immune-IgG control (Fig. 5D). INT-767 significantly increased PGC1α occupancy at the Tgr5 promoter consistent with the reporter assay in Fig. 5, B and D. OCA and INT-767 did not significantly affect the occupancy of nuclear receptor co-repressor 1 (NCoR1) to the Tgr5 promoter. Overall, these results suggest that the IR1 motif on the Tgr5 promoter binds FXR/RXRα in the present of OCA and INT-767. Activation of FXR by INT-767, but not OCA, recruits PGC1α to stimulate Tgr5 gene transcription indicating OCA is a weaker FXR agonist than INT-767.

Figure 5.

TGR5 promoter has a functional FXRE. A, FXRE in the Tgr5 proximal promoter. Analysis of the human TGR5 promoters identified a putative inverted repeat of hormone-response element with 1 nucleotide spacing (IR1). Nucleotide sequence alignment shows conserved DNA sequence between human Tgr5 and mouse Tgr5 gene proximal promoter region. B, luciferase reporter assays for a functional FXRE. STC-1 cells were transiently transfected with human (h) Tgr5 (hTGR5) or mutant (Mu) hTgr5 promoter (sequence shown in A) reporter plasmid for 48 h. Cells were treated with OCA or INT-767 overnight. Firefly luciferase activity was expressed as random luciferase unit (RLU) normalized to β-gal activity. The transfection assay was performed in triplicate, and the assay was repeated in triplicate. * and # indicate statistically significant difference of wild-type versus mutant and treated versus vehicle control (p ≤ 0.05), respectively. Student's t test was used for statistical analysis. C, EMSA of FXR binding to the Tgr5 promoter. EMSA was performed using the double-stranded DNA probe designed according to the FXRE identified on the human Tgr5 promoter. Biotin-labeled probe was incubated with in vitro transcribed and translated (TNT) FXR and RXRα lysates for 1 h. The probes were resolved on non-denatured gel. The SHP probe was used as a positive control for FXR and RXRα binding. Unlabeled probe (cold) was used for competition assay. Mutant TGR5 probe (Mu) with mutations in FXRE (shown in A) was used for binding specificity. D, ChIP of FXR and RXRα occupancy and co-regulator recruitment to FXRE on the Tgr5 promoter. ChIP was performed using nuclear extracts isolated from the proximal ileum of mice treated with INT-767, OCA, or vehicle (CMC), and chromatin was immunoprecipitated using specific antibodies against FXR, RXR, PGC1α, and NcoRI. The PCR primer pair used for amplification of the mouse Tgr5 promoter region is shown on the top of the graph. The Ct values were normalized with 10% input (pre-immune IgG) and relative abundance was calculated with respect to vehicle control. The results were expressed as means ± S.E. * indicates statistically significant difference of treated versus vehicle control (p ≤ 0.05). Student's t test was used for statistical analysis.

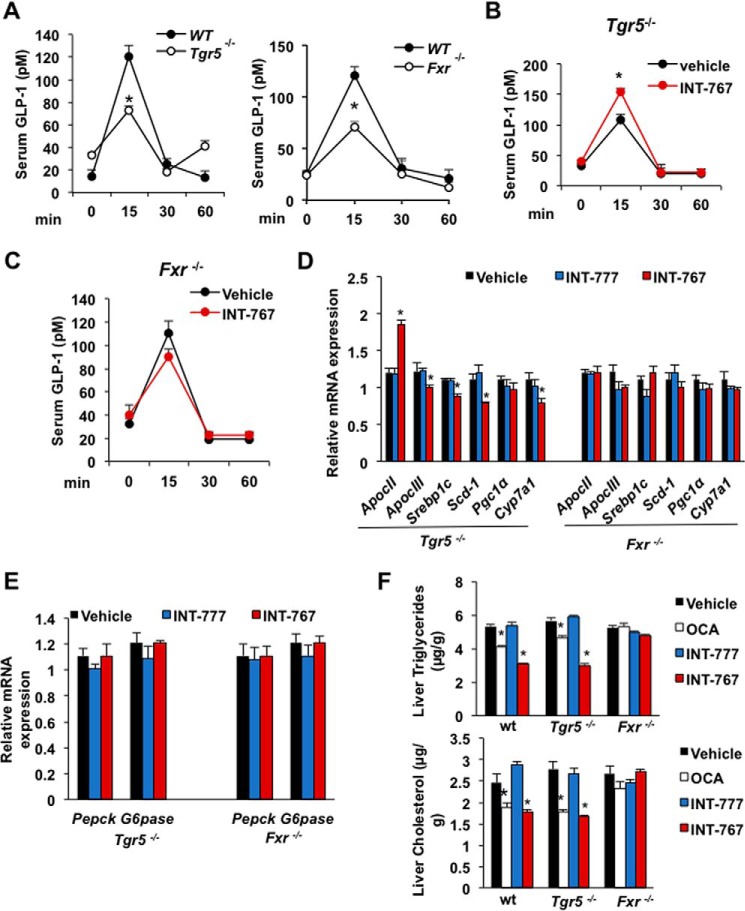

Both FXR and TGR5 are involved in stimulating GLP-1 secretion in vivo

The role of intestinal FXR and TGR5 in stimulating glucose-induced GLP-1 secretion was further examined using wild-type, Fxr−/−, and Tgr5−/− mice. Glucose-induced GLP-1 secretion in serum was reduced by about 40% in Tgr5−/− or Fxr−/− mice as compared with wild-type mice indicating both receptors are involved in glucose-induced GLP-1 secretion (Fig. 6A). In Tgr5−/− mice, FXR is expressed, and INT-767 treatment significantly stimulated GLP-1 secretion indicating that activation of FXR stimulated GLP-1 secretion (Fig. 6B). In Fxr−/− mice, TGR5 is expressed at lower levels (see Fig. 4B), and INT-767 did not significantly increase GLP-1 secretion (Fig. 6C). These results indicate that both FXR and TGR5 are involved in stimulating GLP-1 secretion. However, FXR plays a critical role in GLP-1 secretion even in the absence of TGR5. To further study the effect of FXR agonists in the regulation of lipid metabolism, FXR target gene mRNA was measured in Tgr5−/− and Fxr−/− mice treated with INT-767 and INT-777. In Tgr5−/− mice, only INT-767 induced ApoCII and reduced ApoCIII, Serb-1c, Scd-1, and Cyp7a1, whereas no changes were observed in Fxr−/− mice, indicating that activation of FXR improved hepatic lipid metabolism in Tgr5−/− mice (Fig. 6D). However, neither INT-767 nor INT-777 inhibited hepatic gluconeogenic gene mRNA expression in Fxr−/− and TGR5−/− mice (Fig. 6E), in contrast to their inhibitory effects on gluconeogenic gene mRNAs in wild-type mice (see Fig. 2C). OCA and INT-767 reduced liver triglycerides and cholesterol in wild-type and Tgr5−/− mice but not Fxr−/− mice (Fig. 6F). These data suggest that FXR and TGR5 play an important role in the regulation of gluconeogenesis, and FXR plays a critical role in regulation of hepatic lipid metabolism.

Figure 6.

Both FXR and TGR5 are involved in stimulating GLP-1 secretion in mice and Glutag cells. A, serum GLP-1 levels were reduced in Tgr5−/− and Fxr−/− mice. Tgr5−/− (n = 8), Fxr−/− (n = 8), and wild-type (n = 8) mice after 10 h of fasting followed by bolus dose of liquid diet (Ensure Plus). B, effect of INT-767 on serum GLP-1 level in Tgr5−/− mice. Mice were orally gavaged with INT-767 (30 mg/kg, n = 8) or vehicle (0.5% CMC, n = 8) after bolus dose of liquid diet. C, effects of INT-767 on serum GLP-1 level in Fxr−/− mice. Mice were orally treated with INT-767 (30 mg/kg, n = 8) or vehicle (n = 8) followed by bolus dose of liquid diet. D, relative mRNA expression of key genes involved in lipid metabolism. Tgr5−/− mice (n = 8) or Fxr−/− mice (n = 8) were gavaged with INT-767 (30 mg/kg), INT-777 (30 mg/kg), or vehicle (0.5% CMC, n = 10). E, effect of FXR agonists on liver gluconeogenic gene expression. Tgr5−/− (n = 8) or Fxr−/− (n = 8) mice were gavaged with INT-767 (30 mg/kg), INT-777 (30 mg/kg), or vehicle (0.5% CMC, n = 10). F, effect of FXR and TGR5 agonists on liver triglycerides and cholesterol. WT, Fxr−/−, and Tgr5−/− mice were gavaged with OCA, INT-777, or INT-767 (30 mg/kg, n = 6 per group). The results were expressed as means ± S.E. * indicates statistically significant difference wild-type (WT) versus Tgr5−/− or Fxr−/− mice (A) or treated versus vehicle control (p ≤ 0.05). A–C, Student's t test was used. D–F, analysis of variance was used for statistical analysis.

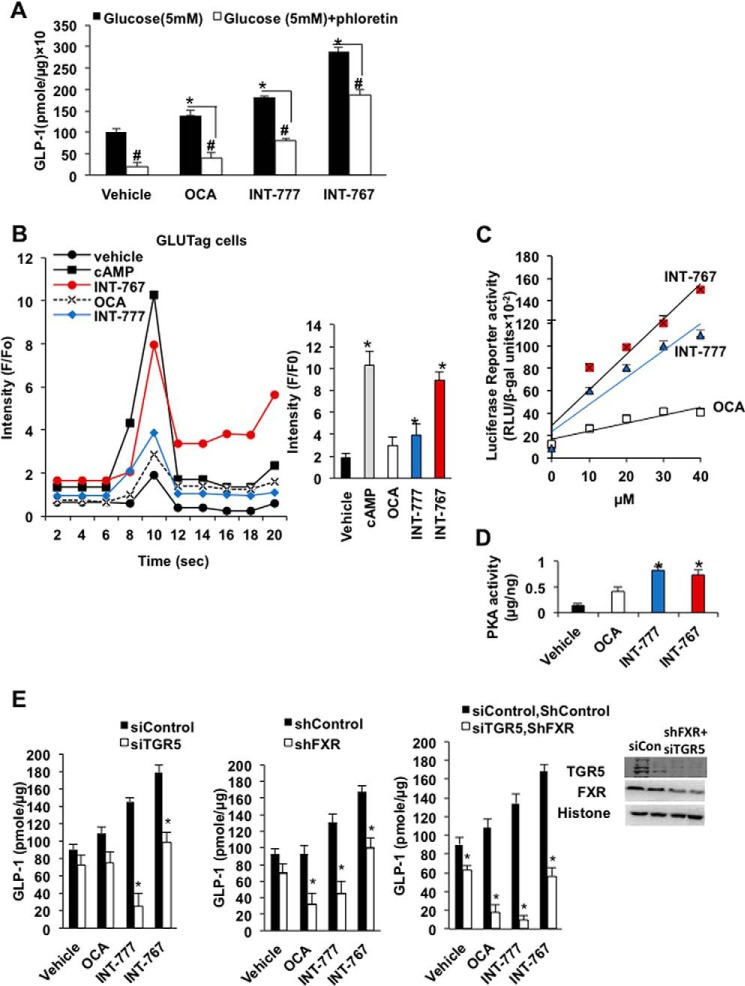

FXR agonists regulate intracellular [Ca2+] and cAMP activity to stimulate glucose-induced GLP-1 secretion from L cells

Intestinal Glutag cells were used to study the mechanism of intestinal FXR and TGR5 signaling in stimulating glucose-induced GLP-1 secretion from L cells, which express both TGR5 and FXR (29). INT-777 and INT-767 significantly stimulated glucose-induced GLP-1 secretion from Glutag cells (Fig. 7A). Addition of the L-type Ca2+ channel inhibitor phloretin reduced the agonist-stimulated and glucose-induced GLP-1 section from Glutag cells indicating that the L-type Ca2+ channels are involved in agonist-stimulated and glucose-induced GLP-1 secretion. Fluorescent Ca2+-binding assay showed that INT-767 was much more potent than OCA and INT-777 in inducing cellular [Ca2+] in Glutag cells (Fig. 7B) and in stimulating cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB) reporter activity in CHO cells overexpressing TGR5 (Fig. 7C). INT-777 and INT-767, but not OCA, stimulated cAMP activity in Glutag cells by PKA assay using Glutag cells (Fig. 7D). RNA silencing was then used to knock down FXR, TGR5, or both FXR and TGR5 in Glutag cells to study the role of FXR and TGR5 in GLP-1 secretion. In Tgr5−/− Glutag cells, the INT-767 and INT-777, but not the OCA-stimulatory effect on GLP-1 secretion, was significantly reduced (Fig. 7E, left panel). In Fxr−/− Glutag cells, the OCA, INT-777, and INT-767 stimulatory effect on GLP-1 secretion was reduced (Fig. 7E, middle panel). In FXR and TGR5 double-deficient Glutag cells (siTgr5/shFxr), INT-767-, OCA-, and INT-777-stimulated GLP-1 secretion was strongly reduced (Fig. 7E, right panel). Overall, these data suggest that activation of both FXR and TGR5 by INT-767 exacerbates glucose-induced GLP-1 secretion from L cells, by stimulating both [Ca2+] and PKA activity.

Figure 7.

Effect of INT-767, OCA, and INT-777 on GLP-1 secretion, cellular [Ca2+]c, and cAMP activity in L cells. A, effects of agonists and L-type Ca2+ channel inhibitor phloretin on glucose-stimulated GLP-1 secretion in Glutag cells. Glutag cells were maintained in 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic media in 24-well plates prior to the experiment. Cells were incubated without glucose media with FXR or TGR5 (10 μm each) agonist or vehicle (DMSO) as described under “Experimental procedures.” GLP-1 was normalized to the amount of protein in the cell and indicated as (pmol/μg). Results were expressed as means ± S.E. Student's t test was used for statistical analysis. * indicates statistically significant difference of serum GLP-1 between ligand-treated versus vehicle (p ≤ 0.05). # represents significant difference of serum GLP-1 level between ligand-treated versus phloretin-treated. B, effects of INT-767, OCA, and INT-777 on cellular [Ca2+] in Glutag cells. Glutag cells were maintained in 96-well plates and incubated with Hanks' balanced salt solution with loading dye as described under “Experimental procedures” using a Ca2+ fluorescence kit. Initial fluorescence readings were obtained without addition of ligands, designated as F0, followed by addition of 10 μm each of OCA, INT-767, INT-777, or 8-Br-cAMP (as a positive control) treatment for 20 s, designated as (F). The results were represented as the ratio F/F0 versus time in seconds. The assay was performed in quadruplet. * indicates statistically significant difference in F/F0-treated versus vehicle (p ≤ 0.05). C, CREB reporter assay in CHO cells. CHO cells stably expressing CREB/luciferase reporter were transfected with 0.1 μg of hTGR5 plasmid and treated with different concentrations of FXR agonist indicated or DMSO as vehicle control. The firefly reporter activity (RLU) was normalized with β-gal activity. The assay was performed in quadruplicate. The results were represented by linear regression analysis. D, PKA activity assay. Glutag cells were treated with 10 μm each agonist for 2 h. Total PKA activity ELISA was used to quantify PKA activity. * indicates statistically significant difference in PKA activity in treated versus vehicle (p ≤ 0.05). E, GLP-1 secretion assay of Glutag cells. Left panel, glucose-induced GLP-1 secretion from Glutag cells deficient in TGR5 (siTGR5) compared with siControl. Middle panel, glucose-induced GLP-1 secretion from Glutag cells deficient in FXR (shFXR) compared with shControl. Right panel, glucose induced GLP-1 secretion from Glutag cells deficient in FXR and TGR5 (shFXR and siTGP5) compared with shControl siTGR5. * indicates statistically significant difference in GLP-1 in treated versus vehicle control (p ≤ 0.05). Upper inset shows immunoblotting analysis of TGR5 and FXR in Fxr and Tgr5-deficient Glutag cells. Student's t test was used for statistical analysis.

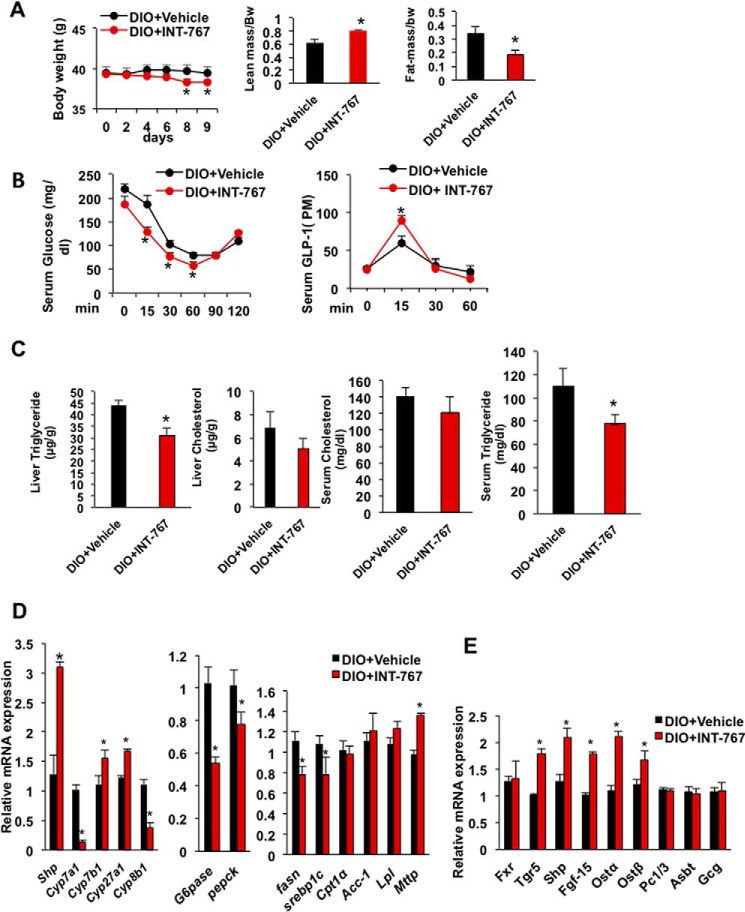

INT-767 improved obesity, insulin sensitivity, and hepatic metabolism in diet-induced obese mice

We then tested the effects of INT-767 treatment to diet-induced obese (DIO) mice. Mice were fed a high fat diet for 5 months, and a group of mice was treated by oral gavage with INT-767 (30 mg/kg) daily for 9 days. Fig. 8A shows that INT-767 treatment significantly reduced body weight of DIO mice in 8–9 days and increased the lean mass to body weight ratio and decreased the fat mass to body weight compared with vehicle-treated DIO mice. Oral insulin tolerance test showed INT-767 significantly improved insulin sensitivity and increased serum GLP-1 secretion (Fig. 8B). Lipid analysis showed that INT-767 significantly reduced liver and serum triglycerides and caused a trend to reduce liver and serum cholesterol levels (Fig. 8C). Furthermore, INT-767 increased mRNA expression levels of Shp, Cyp7b1, and Cyp27a1 and decreased Cyp8b1 in bile acid synthesis; it decreased G6pase and Pepck in gluconeogenesis but decreased Srebp-1c and Fasn in lipogenesis; and it increased microsomal triglyceride transport protein (Mttp) involved in VLDL assembly and secretion but not Cpt1, Acc-1, and lipoprotein lipase (Lpl) in lipolysis. INT-767 induced intestinal FXR target genes, Tgr5, Shp, Fgf15, organic solute transporter α (Ostα), and Ostβ mRNA expression in DIO mice (Fig. 8E). These data support that INT-767 inhibited classic bile acid synthesis, although it stimulated the alternative bile acid synthesis to stimulate bile acid signaling to improve hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism. INT-767 reduced fatty acid synthesis but had no effect on fatty acid oxidation. INT-767 stimulation of FXR signaling in the intestine contributed to increasing GLP-1 secretion to improve obesity and insulin sensitivity in DIO mice.

Figure 8.

INT-767 improved obesity, insulin sensitivity, and hepatic metabolism in diet-induced obese mice. C57BL/6J mice were fed a high fat diet for 5 months (DIO). A group of mice were gavaged with 30 mg/kg INT-767 (n = 9) or vehicle (n = 9) for 9 days, and mice were killed after 6 h of fasting. A, INT-767 reduced body weight and increased lean mass and reduced fat mass in DIO mice as measured by EchoMRI. B, INT-767 improved insulin tolerance and GLP-1 secretion in DIO mice. C, INT-767 significantly reduced triglyceride and tends to reduce liver cholesterol and serum triglyceride and cholesterol levels. D, INT-767 altered liver bile acid synthesis and fatty synthesis and mRNA expression. E, INT-767-induced FXR target gene mRNA expression in mouse intestine. Real-time PCR analysis of liver and intestine mRNA is relative to vehicle control as 1. All results were expressed as means ± S.E. Statistical significance was calculated using Student's t test. * indicates significant difference INT-767-treated versus vehicle control, p ≤ 0.05.

Discussion

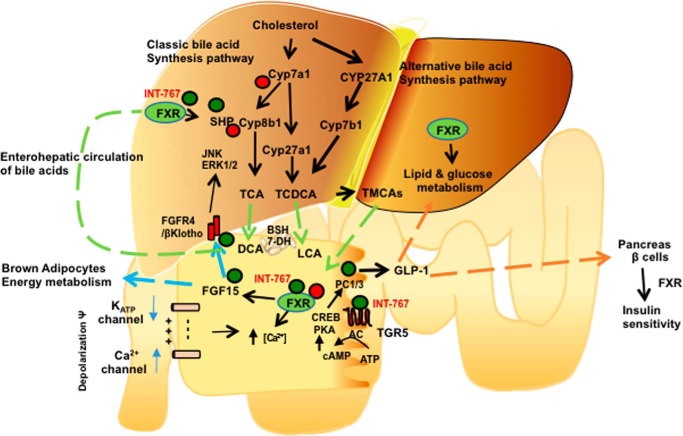

This study uncovered a critical role and mechanism of activation of FXR in improving glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, and lipid metabolism (Fig. 9). This study reports for the first time that the dual FXR and TGR5 agonist INT-767 induces Tgr5 and Pc1/3 gene expression and increases cellular [Ca2+] and cAMP activity, whereas a weaker FXR agonist OCA did not stimulate [Ca2+] or cAMP activity, and finally, the TGR5 agonist INT-777 stimulates cAMP activity but did not increase [Ca2+]. INT-767 was most effective in improving glucose tolerance and hepatic insulin signaling, whereas OCA was effective in improving hepatic lipid metabolism. It has been reported previously that T-CDCA depolarizes membrane potential to trigger [Ca2+] increase and to stimulate insulin secretion from pancreatic β cells (30). Activation of FXR leads to closure of KATP channel (ABCC8) to depolarize membrane potential and increase [Ca2+] (30). Our data show that an L-type Ca2+ channel inhibitor reduced glucose-stimulated GLP-1 secretion from Glutag cells. Activation of FXR also stimulates AKT phosphorylation to increase translocation of glucose transporter 2 to the plasma membrane to stimulate insulin secretion in β cells (31). Similar mechanisms may be involved in FXR stimulation of glucose-stimulated GLP-1 secretion in L cells (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Mechanisms of intestinal FXR and TGR5 cross-talk in the regulation of GLP-1 secretion, hepatic bile aid synthesis, glucose and lipid metabolism, and insulin and glucose sensitivity. In the liver, the classic bile acid synthesis is initiated by cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1 catalyze cholic acid synthesis, and sterol 27-hydroxylase catalyzes steroid side-chain oxidation to synthesize CA and CDCA, which are conjugated to taurine (T)). The alternative pathway is initiated by Cyp27a1 and oxysterol 7α-hydroxylase (Cyp7b1) to synthesize mainly CDCA. INT-767 activates FXR/SHP in hepatocytes to repress Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1 and stimulate Cyp7b1 and Cyp27a1 expression to improve glucose and lipid metabolism. In intestinal L cells, INT-767 activates FXR, which stimulates TGR5 and prohormone convertase 1/3 (PC1/3) expression. FXR also induces FGF15, which stimulates energy metabolism in brown adipocytes. FGF15 activates hepatic FGFR4/βKlotho signaling to inhibit Cyp7a1 via JNK/ERK1/2 pathway. TGR5 activation stimulates adenylyl cyclase (AC) to increase cAMP, which activates protein kinase A (PKA) and phosphorylates and activates CREB to increase PC1/3 transcription. PC1/3 splices pre-proglucagon to GLP-1. INT-767 increases intracellular [Ca2+] and cAMP activity. INT-767 activation of FXR may depolarize membrane potential by inhibiting KATP channel to stimulate Ca2+ uptake through Ca2+ channels. Ca2+ stimulates GLP-1 secretion from L cells. GLP-1 and FXR stimulate insulin synthesis and secretion from pancreatic β cells.

This study shows that INT-767 strongly inhibits Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1 expression in the classic bile acid synthesis pathway but stimulates Cyp7b1 and Cyp27a1 expression in the alternative pathway and only slightly reduces total bile acid pool size (Fig. 9). Switching from the classic pathway to the alternative pathway reduces TCA and CA and increases T-β-MCA to decrease hydrophobicity of bile. The observed effect of INT-767 on bile acid composition is consistent with our previous report that TGR5 plays a critical role in regulating bile acid composition and fasting induced hepatic steatosis (22). In Tgr5−/− mice, expression of Cyp7b1, a sexually dimorphic and male predominant gene, was reduced (22), consistent with increased Cyp7b1 expression by INT-767 in wild-type mice in this study. In addition, INT-767 activates intestinal FXR to induce intestinal FGF15, which may further inhibit Cyp7a1 via activation of FGF receptor 4 in hepatocytes (Fig. 9). Furthermore, INT-767 treatment rapidly reduced body weight, increased lean mass and reduced fat mass, increased serum GLP-1, and improved insulin sensitivity and hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism in DIO mice. In diabetic mice, hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia increases bile acid synthesis due to increased histone acetylation on the Cyp7a1 gene promoter (32). INT-767 reduces expression of hepatic Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1 in the classic bile acid synthesis pathway but stimulates Cyp7b1 and Cyp27a1 in the alternative bile acid synthesis pathway in DIO mice. In the intestine, INT-767 stimulated FXR signaling indicated by increasing Tgr5, Shp, Ostα, and Ostβ expression to increasing GLP-1 secretion and improving insulin sensitivity in DIO mice. In diabetic patients, serum bile acid concentrations and the 12α-hydroxylated bile acids (CA and DCA) to non-12α-hydroxylated bile acid ratio (CDCA and LCA) are increased (33). INT-767 may reduce cholic acid synthesis to reduce intestinal absorption of dietary cholesterol and fats and serum cholesterol and triglycerides and to improve glycemic control and diabetes.

Activation of intestinal FXR signaling was shown to protect against NAFLD (13), but deficiency of intestinal FXR was also shown to prevent diet-induced obesity, diabetes, and NAFLD (11, 12). Different mechanisms may be involved in the paradoxical effects of intestinal FXR signaling on obesity and diabetes. Our current results indicate that INT-767 has two actions in the intestine, stimulating production of GLP-1 as well as FGF15 to stimulate hepatic insulin signaling and improve glucose and lipid metabolism. Deficiency in intestinal FXR or antagonizing intestinal FXR activity would alter the gut microbiome and result in stimulating bile acid synthesis to protect against diet-induced obesity and diabetes. Increasing bile acid synthesis and altering bile acid composition by shifting bile acid synthesis from the classic pathway to the alternative bile acid pathway have been shown to protect against obesity and diabetes in Cyp7a1-transgenic mice (34). Others reported that activation of FXR by the FXR agonist GW4064 partially reduced glucose-induced GLP-1 production by inhibiting glycolysis-generated ATP concentration and proglucagon gene expression (29), which is in contrast to our current study. GW4064 is a potent FXR agonist but has very low bioactivity. OCA is a weaker FXR agonist than INT-767 and is not as effective as INT-767 in stimulating Tgr5 reporter activity. Nevertheless, the results from this study using a potent FXR and TGR5 dual agonist strongly support the present finding that FXR and TGR5 may coordinately stimulate secretion of GLP-1 and FGF15 to stimulate insulin and glucose tolerance in mice.

The gut microbiome, the gut-produced hormones GLP-1 and FGF15, and bile acids play critical roles in the regulation of liver metabolic homeostasis. This study provides a mechanism and supports recent findings that vertical sleeve gastrectomy does not improve insulin and glucose tolerance in Fxr- and Tgr5-deficient mice, suggesting that both bile acid-activated receptors are involved in improving insulin sensitivity after bariatric surgery (35, 36). In gastric bypass surgery of obese and diabetic patients, the rapid improvement of insulin sensitivity and glycemic control before weight reduction is positively correlated with increased serum bile acids and GLP-1 (37, 38). These studies, in conjunction with our current results, may indicate a pivotal role of bile acid-activated receptors in diabetes. In conclusion, this study discovers a novel mechanism whereby activation of FXR induces TGR5, which alters bile acid composition and increases FGF15, and both FXR and TGR5 may coordinately stimulate GLP-1 secretion from intestinal L cells to improve hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism. FXR and TGR5 dual agonists like INT-767 may thus represent promising therapeutic agents for the treatment of cholestasis, NAFLD, and diabetes (25, 26, 39).

Experimental procedures

Mice

Male wild-type C57BL/6J and 8-week-old DIO mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Male Fxr−/− mice (8) and Tgr5−/− mice (40) are on C57BL/6J genetic background and were maintained in an AAALAC certified animal facility at Northeast Ohio Medical University. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Northeast Ohio Medical University approved all animal protocols. DIO mice were maintained in the facility and fed a high fat diet (D12492, 60% calorie from fat, Research Diet) for 10 more weeks. Other mice were used at 12–16 weeks of age and were maintained on a standard chow diet and water ad libitum and housed in a room with a 12-h light (6 a.m. to 6 p.m.) and 12-h dark (6 p.m. to 6 a.m.) cycle.

FXR agonist treatment and GLP-1 secretion assay

Mice (wild-type C57BL/6J, Fxr−/−, and Tgr5−/−) were treated by oral gavage with the FXR-selective agonist OCA (30 mg/kg, Intercept Pharmaceuticals, New York), INT-777 (30 mg/kg, Intercept Pharmaceuticals), or the FXR and TGR5 dual agonist INT-767 (20) (30 mg/kg, Intercept Pharmaceuticals), once a day for 7–9 days. OCA and INT-767 were dissolved in carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC, 0.5% in water). At 17 weeks, DIO mice were treated by oral gavage with INT-767 (30 mg/g) or vehicle for 7–9 days.

For GLP-1 secretion assays, mice (wild-type, Fxr−/−, and Tgr5−/−, DIO) were treated by oral gavage with FXR agonists once a day for 6 days. On the 7th day, the mice were fasted for 10 h and orally gavaged with FXR agonists. One h before killing, the mice were orally gavaged with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, sitagliptin (3 mg/kg), and liquid diet (Ensure Plus, 10 ml/kg, 1.5 calories/ml: 15% protein, 57% carbohydrate, and 28% fat) to stimulate GLP-1 secretion as described (16). Blood samples were collected immediately (time 0), 15 and 30 min after liquid diet gavage, and serum GLP-1 levels were assayed using a GLP-1 (7–37) ELISA kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Knockdown of FXR and TGR5 in Glutag cells

To knock down FXR expression in Glutag cells, shRNA against mouse FXR (in pRN-US neomycin-resistant vector, pRN-luciferase control vector (shControl) Genescript, Piscataway, NJ, provided by Dr. Li Wang, University of Connecticut, Storrs) was transfected into Glutag cells in 6-well plates using Lipofectamine (Clontech) for 6 h. Culture media were supplemented with neomycin (30 μg/ml), and resistant cells were selected for the generation of stable transfected cells lacking FXR (shFxr). Similarly, siRNA against mouse TGR5 (siTgr5, 500 ng, Dharmacon Scientific, Lafayette, CO) and siRNA scrambled control (siControl, 500 ng, Dharmacon Scientific) were transfected to naive Glutag cells and FXR-deficient Glutag cells to generate Glutag cells deficient of TGR5 (siTgr5), and both FXR and TGR5 (siTGR5, shFXR), respectively. Double deletion of FXR and TGR5 in Glutag cells was confirmed by immunoblotting analysis using ab-TGR5 (catalog no. LS-C47388, LS Bioscience, Seattle, WA) and ab-FXR (catalog no. ab85605, Abcam, Cambridge, MA).

Fluorescent Ca2+-binding assay

Glutag cells were maintained in 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in 96-well plates. Cellular [Ca2+] was measured using a FluoForte calcium assay kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY). This assay measures intracellular Ca2+-binding activity in response to the activation of G-protein-coupled receptor. Prior to the experiment, the cells were washed and loaded with FluoForte dye for 1 h according to manufacturer's protocol. Initial fluorescence was measured at 450 nm without ligand and designated as F0. Then 10 μm each of OCA, INT-767, and INT-777 was added to activate TGR5 and/or FXR signaling to stimulate intracellular [Ca2+] binding, and 8-Br-cAMP was added as a positive control to stimulate cellular [Ca2+]. Fluorescence (F) was measured at 525 nm (excitation, 490 nm), every 2 s using a Synergy 4 plate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT). The results were represented as F/F0 versus time (seconds).

Bile acid composition analysis

For bile acid quantitation in serum, ileum, colon, and gallbladder, d5-TCA at 1 μm was used as an internal standard. Samples were prepared by acetonitrile precipitation, and the supernatants were further diluted with 0.1% formic acid. The bile acid concentrations were determined by a UPLC/Synapt G2-Si QTOFMS system (Waters Corp.) with an ESI source. Chromatographic separation was archived on an Acquity BEH C18 column (100 × 2.1-mm inner diameter, 1.7 μm, Waters Corp.). The mobile phase consisted of a mixture of 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B). The gradient elution was applied. Column temperature was maintained at 45 °C, and the flow rate was 0.4 ml/min. MS detection was operated in negative mode. A mass range of m/z 50 to 850 was acquired. All bile acid standards were purchased from Sigma or Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) (41).

Oral glucose and insulin tolerance tests

For glucose tolerance testing, wild-type mice were fasted 6 h and treated by oral gavage with glucose (2 g/kg). For oral insulin tolerance test, DIO mice were fasted for 6 h and injected i.p. with insulin (0.5 units/kg). Blood samples were collected via tail vein, and serum glucose was measured over 2 h using a OneTouch Ultra Mini glucometer (LifeScan; Milpitas, CA).

Lipid analysis

Mice were fasted for 6 h, and liver tissues were homogenized with 2:1 chloroform/isopropyl alcohol followed by evaporation at 60 °C. The resulting lipids were dissolved in water with 2% Triton X-100. Liver and serum cholesterol and triglycerides were analyzed using lipid analysis kits from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Cell culture

Murine enteroendocrine STC-1 and Glutag cells express both FXR and TGR5 and were used to study GLP-1 secretion (15, 42). Glutag cells (provided by Dr. Frank Anania, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, with the permission of Dr. Daniel Drucker, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada) were maintained in DMEM containing 25 mm glucose with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic media. STC-1 and CHO cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, and cultured in DMEM (10% FBS, 1% antibiotic).

GLP-1 secretion assay in cultured cells

Glutag cells were incubated in DMEM without glucose and treated with 10 μm OCA, INT-767, INT-777, or vehicle (DMSO) for 8 h. Culture media were replaced by DMEM containing 5 mm glucose. Culture media was collected for GLP-1 assay after incubation for 3 h, with or without treatment with the L-type Ca2+ inhibitor phloretin (5 μm, Sigma). Cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). GLP-1 levels were measured in cell lysates and normalized to the total protein in cell lysates.

ChIP assay

Nuclei were isolated from the proximal ileum of mice treated with OCA or INT-767. ChIP assays were performed with a ChIP assay kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) as described previously (43). Briefly, the chromatin-containing DNA and proteins in nuclear extracts were cross-linked by formaldehyde, sonicated to fragments of about 500–600 bp, and immunoprecipitated with an antibody against FXR, RXRα, PGC-1α, or NCoR1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). SYBR Green primers for real-time PCR were designed to amplify the IR1 sequence on the mouse Tgr5 promoter and to quantify the abundance of FXR, RXR, PGC-1α, and NCoR1 on the Tgr5 promoter. Primer pairs used were as follows: forward primer, 5′-GCCAGTTACTGTCCTCTCTTG-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-CCCTGGGCAGCTATGTTTAT-3′.

Whole gels were exposed to films and scanned using a scanner. Bands were sliced from the whole gels based on their absence in knock-out mice or intensity change by agonists.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Probes specific for TGR5 and SHP promoters were designed, purchased, and labeled with biotin. Single-stranded oligonucleotides for synthesis of double-stranded probes were from Eurofins Genomics (Huntsville, AL): SHP, forward, 5′-CTGCCCTTAGGGACATTGATCCTTAGGCAAATCTCCTATCTGATCAATCAGCTGCTA-3′; human TGR5 forward, 5′-GTTTATGGGCTGGAAGTCCACCCGGAGGCTGCTCACTGAGCTGTGTGATGGCTAT-3′.

Immunoblotting analysis

Total tissue and cell lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and proteins were resolved on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Monoclonal antibodies against AKT and pAKT473 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (catalog no. 9272 and 9271). Anti-TGR5 antibody was purchased from LS Bioscience (catalog no. LS-C47388, Seattle). Loading control histone blot was performed by stripping and re-probing the blot with histone antibody (catalog no. 9715, Cell Signaling Technology). For analysis of Cyp7a1, Cyp8b1, and Cyp7b1, microsomal fractions were isolated from mouse liver (43). Immunoblot analysis was performed using polyclonal antibodies against regulatory enzymes CYP7A1 and CYP8B1 (catalog no. Sc25536 and Sc23515, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and CYP7B1 (Ab136801, Abcam). Liver lysates were used for immunoblotting of mitochondrial CYP27A1 (catalog no. Ab126785, Abcam). Calnexin (catalog no. 2679, Cell Signaling) was used as loading control for microsomes, and GAPDH (catalog no. 2118, Cell Signaling) was used as a loading control for liver lysates. Immunoblots were developed using ECL fast Western blot kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and chemiluminescence was visualized using file (Eastman Kodak Co.) or ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare) and quantified by slicing relevant bands from the whole gels, which were verified by molecular weight standard as well as their absence in knock-out mice or induction by agonists in mice or cell lines. Band intensity was quantified by ImageJ software.

Luciferase reporter assay

FXRE (IR1, nt −260 to −247) on the human TGR5 and mouse Tgr5 gene promoters was identified by NUBI scans for transcription factor-binding site. The FXRE in the human TGR5 promoter sequence (NM_001077191) was conserved in the mouse TGR5 promoter (NM_174985.1) in the region between nt −500 and −298. For construction of human TGR5 promoter/luciferase reporter, human TGR5 promoter (nt +1990/−10) was amplified using human genomic DNA (Promega Corp., Madison, WI). The amplified PCR fragment was cloned into the MluI and KpnI sites in pGL3 basic luciferase reporter plasmid (Promega Corp.). A QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technology, Santa Clara, CA) was used to mutate the FXRE according to the manufacturer's protocol. STC-1 cells were grown in DMEM to about 80% confluence in 24-well tissue culture plates. TGR5 luciferase reporter and β-galactosidase (β-gal) expression plasmid (0.1 μg each) were co-transfected into STC-1 cells using Trans-Fast reagent (Promega Corp.) following the manufacturer's instructions. After 48 h, cells were treated with 10 μm OCA or INT-767 for 12 h. Reporter activity was normalized to β-gal activity to adjust transfection efficiency. The assays were performed in triplicate, and each experiment was repeated at least three times. Data were expressed as means ± S.E. For CREB reporter assay, CHO cells cultured in DMEM were co-transfected with CREB luciferase reporter plasmid (0.2 μg), TGR5 expression plasmids (0.1 μg), and β-gal plasmid (0.05 μg) (Origene, Rockville, MD), and reporter activity was assayed as described above.

Bile acid pool size

C57BL6J mice were treated with INT-767 (30 mg/kg, n = 8), OCA (30 mg/kg, n = 8), INT-777 (30 mg/kg, n = 8), or vehicle (CMC) for 9 days. Mice were fasted for 6 h before sacrifice, and bile acids were isolated from 100 mg of liver and whole intestine and whole gallbladder by a series of ethanol and methanol extractions overnight at 65 °C. Bile acid content was quantified by Genzyme Diagnostic kit (Cambridge, MA), and bile acid pool size was determined by totaling bile acids liver, gallbladder, and intestine.

Quantitative real-time PCR assay (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated with Tri-Reagent (Sigma). All primers/probe sets for qPCR were ordered from TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Amplification of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) was used as an internal control. Relative mRNA expression was quantified using the comparative CT (ΔCt) method and expressed as 2−ΔΔCt.

PKA activity assay

Glutag cells were maintained in DMEM in 24-well plates and were treated with 10 μm each of OCA, FEX, INT-767, or INT-777 for 2 h. Cells were harvested, lysed, and analyzed with a PKA kinase activity assay kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

All experimental data are presented as means ± S.E. Statistical analysis was performed either by Student's t test for two variants or analysis of variance for multiple variants as specified. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significantly different.

Author contributions

P. P. contributed to the design and performance of most experiments, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript; H. L. contributed to performance of animal experiments; S. B. contributed to breeding mice and preparation of the manuscript; C. X. and K. W. K. analyzed bile acid composition by HPLC-MS; F. J. G. contributed to data analysis and manuscript writing. J. Y.L. C. contributed to concept design, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK58379 and DK44442 from NIDDK (to J. Y. L. C.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- FXR

- farnesoid X receptor

- CA

- cholic acid

- CDCA

- chenodeoxycholic acid

- CYP7A1

- cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase

- CREB

- cAMP-response element-binding protein

- DCA

- deoxycholic acid

- LCA

- lithocholic acid

- FGF15

- fibroblast growth factor 15

- NAFLD

- non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- OCA

- obeticholic acid

- PC1/3

- prohormone convertase 1/3

- SHP

- small heterodimer partner

- DIO

- diet-induced obese

- qPCR

- quantitative real-time PCR

- MCA

- muricholic acid

- 8-Br-cAMP

- cyclic 8-bromo-AMP

- FXRE

- FXR response element

- nt

- nucleotide

- RXR

- retinoid X receptor

- h

- human

- CMC

- critical micelle concentration

- T

- taurine.

References

- 1. Lefebvre P., Cariou B., Lien F., Kuipers F., and Staels B. (2009) Role of bile acids and bile acid receptors in metabolic regulation. Physiol. Rev. 89, 147–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li T., and Chiang J. Y. (2014) Bile acid signaling in metabolic disease and drug therapy. Pharmacol. Rev. 66, 948–983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chiang J. Y. (2009) Bile acids: regulation of synthesis. J. Lipid Res. 50, 1955–1966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takahashi S., Fukami T., Masuo Y., Brocker C. N., Xie C., Krausz K. W., Wolf C. R., Henderson C. J., and Gonzalez F. J. (2016) Cyp2c70 is responsible for the species difference in bile acid metabolism between mice and humans. J. Lipid Res. 57, 2130–2137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kawamata Y., Fujii R., Hosoya M., Harada M., Yoshida H., Miwa M., Fukusumi S., Habata Y., Itoh T., Shintani Y., Hinuma S., Fujisawa Y., and Fujino M. (2003) A G-protein-coupled receptor responsive to bile acids. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 9435–9440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maruyama T., Miyamoto Y., Nakamura T., Tamai Y., Okada H., Sugiyama E., Nakamura T., Itadani H., and Tanaka K. (2002) Identification of membrane-type receptor for bile acids (M-BAR). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 298, 714–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Inagaki T., Choi M., Moschetta A., Peng L., Cummins C. L., McDonald J. G., Luo G., Jones S. A., Goodwin B., Richardson J. A., Gerard R. D., Repa J. J., Mangelsdorf D. J., and Kliewer S. A. (2005) Fibroblast growth factor 15 functions as an enterohepatic signal to regulate bile acid homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2, 217–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sinal C. J., Tohkin M., Miyata M., Ward J. M., Lambert G., and Gonzalez F. J. (2000) Targeted disruption of the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR impairs bile acid and lipid homeostasis. Cell 102, 731–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Watanabe M., Houten S. M., Wang L., Moschetta A., Mangelsdorf D. J., Heyman R. A., Moore D. D., and Auwerx J. (2004) Bile acids lower triglyceride levels via a pathway involving FXR, SHP, and SREBP-1c. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 1408–1418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wagner M., Zollner G., and Trauner M. (2011) Nuclear receptors in liver disease. Hepatology 53, 1023–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jiang C., Xie C., Li F., Zhang L., Nichols R. G., Krausz K. W., Cai J., Qi Y., Fang Z. Z., Takahashi S., Tanaka N., Desai D., Amin S. G., Albert I., Patterson A. D., and Gonzalez F. J. (2015) Intestinal farnesoid X receptor signaling promotes nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 386–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jiang C., Xie C., Lv Y., Li J., Krausz K. W., Shi J., Brocker C. N., Desai D., Amin S. G., Bisson W. H., Liu Y., Gavrilova O., Patterson A. D., and Gonzalez F. J. (2015) Intestine-selective farnesoid X receptor inhibition improves obesity-related metabolic dysfunction. Nat. Commun. 6, 10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fang S., Suh J. M., Reilly S. M., Yu E., Osborn O., Lackey D., Yoshihara E., Perino A., Jacinto S., Lukasheva Y., Atkins A. R., Khvat A., Schnabl B., Yu R. T., Brenner D. A., et al. (2015) Intestinal FXR agonism promotes adipose tissue browning and reduces obesity and insulin resistance. Nat. Med. 21, 159–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Keitel V., Donner M., Winandy S., Kubitz R., and Häussinger D. (2008) Expression and function of the bile acid receptor TGR5 in Kupffer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 372, 78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Katsuma S., Hirasawa A., and Tsujimoto G. (2005) Bile acids promote glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion through TGR5 in a murine enteroendocrine cell line STC-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 329, 386–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harach T., Pols T. W., Nomura M., Maida A., Watanabe M., Auwerx J., and Schoonjans K. (2012) TGR5 potentiates GLP-1 secretion in response to anionic exchange resins. Sci. Rep. 2, 430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mojsov S., Heinrich G., Wilson I. B., Ravazzola M., Orci L., and Habener J. F. (1986) Preproglucagon gene expression in pancreas and intestine diversifies at the level of post-translational processing. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 11880–11889 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fehmann H. C., and Habener J. F. (1992) Insulinotropic hormone glucagon-like peptide-I(7–37) stimulation of proinsulin gene expression and proinsulin biosynthesis in insulinoma β TC-1 cells. Endocrinology 130, 159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Parker H. E., Wallis K., le Roux C. W., Wong K. Y., Reimann F., and Gribble F. M. (2012) Molecular mechanisms underlying bile acid-stimulated glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion. Br. J. Pharmacol. 165, 414–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thomas C., Gioiello A., Noriega L., Strehle A., Oury J., Rizzo G., Macchiarulo A., Yamamoto H., Mataki C., Pruzanski M., Pellicciari R., Auwerx J., and Schoonjans K. (2009) TGR5-mediated bile acid sensing controls glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 10, 167–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Watanabe M., Houten S. M., Mataki C., Christoffolete M. A., Kim B. W., Sato H., Messaddeq N., Harney J. W., Ezaki O., Kodama T., Schoonjans K., Bianco A. C., and Auwerx J. (2006) Bile acids induce energy expenditure by promoting intracellular thyroid hormone activation. Nature 439, 484–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Donepudi A. C., Boehme S., Li F., and Chiang J. Y. (2017) G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor plays a key role in bile acid metabolism and fasting-induced hepatic steatosis in mice. Hepatology 65, 813–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hirschfield G. M., Mason A., Luketic V., Lindor K., Gordon S. C., Mayo M., Kowdley K. V., Vincent C., Bodhenheimer H. C. Jr., Parés A., Trauner M., Marschall H. U., Adorini L., Sciacca C., Beecher-Jones T., et al. (2015) Efficacy of obeticholic acid in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and inadequate response to ursodeoxycholic acid. Gastroenterology 148, 751–761,e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Neuschwander-Tetri B. A., Loomba R., Sanyal A. J., Lavine J. E., Van Natta M. L., Abdelmalek M. F., Chalasani N., Dasarathy S., Diehl A. M., Hameed B., Kowdley K. V., McCullough A., Terrault N., Clark J. M., Tonascia J., et al. (2015) Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 385, 956–965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rizzo G., Passeri D., De Franco F., Ciaccioli G., Donadio L., Rizzo G., Orlandi S., Sadeghpour B., Wang X. X., Jiang T., Levi M., Pruzanski M., and Adorini L. (2010) Functional characterization of the semisynthetic bile acid derivative INT-767, a dual farnesoid X receptor and TGR5 agonist. Mol. Pharmacol. 78, 617–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McMahan R. H., Wang X. X., Cheng L. L., Krisko T., Smith M., El Kasmi K., Pruzanski M., Adorini L., Golden-Mason L., Levi M., and Rosen H. R. (2013) Bile acid receptor activation modulates hepatic monocyte activity and improves nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 11761–11770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miyazaki-Anzai S., Masuda M., Levi M., Keenan A. L., and Miyazaki M. (2014) Dual activation of the bile acid nuclear receptor FXR and G-protein-coupled receptor TGR5 protects mice against atherosclerosis. PLoS One 9, e108270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xu Y., Li F., Zalzala M., Xu J., Gonzalez F. J., Adorini L., Lee Y. K., Yin L., and Zhang Y. (2016) Farnesoid X receptor activation increases reverse cholesterol transport by modulating bile acid composition and cholesterol absorption in mice. Hepatology 64, 1072–1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Trabelsi M. S., Daoudi M., Prawitt J., Ducastel S., Touche V., Sayin S. I., Perino A., Brighton C. A., Sebti Y., Kluza J., Briand O., Dehondt H., Vallez E., Dorchies E., Baud G., et al. (2015) Farnesoid X receptor inhibits glucagon-like peptide-1 production by enteroendocrine L cells. Nat. Commun. 6, 7629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Düfer M., Hörth K., Wagner R., Schittenhelm B., Prowald S., Wagner T. F., Oberwinkler J., Lukowski R., Gonzalez F. J., Krippeit-Drews P., and Drews G. (2012) Bile acids acutely stimulate insulin secretion of mouse beta-cells via farnesoid X receptor activation and K(ATP) channel inhibition. Diabetes 61, 1479–1489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Renga B., Mencarelli A., Vavassori P., Brancaleone V., and Fiorucci S. (2010) The bile acid sensor FXR regulates insulin transcription and secretion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1802, 363–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li T., Francl J. M., Boehme S., Ochoa A., Zhang Y., Klaassen C. D., Erickson S. K., and Chiang J. Y. (2012) Glucose and insulin induction of bile acid synthesis: mechanisms and implication in diabetes and obesity. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 1861–1873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Haeusler R. A., Astiarraga B., Camastra S., Accili D., and Ferrannini E. (2013) Human insulin resistance is associated with increased plasma levels of 12α-hydroxylated bile acids. Diabetes 62, 4184–4191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li T., Owsley E., Matozel M., Hsu P., Novak C. M., and Chiang J. Y. (2010) Transgenic expression of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase in the liver prevents high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice. Hepatology 52, 678–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ryan K. K., Tremaroli V., Clemmensen C., Kovatcheva-Datchary P., Myronovych A., Karns R., Wilson-Pérez H. E., Sandoval D. A., Kohli R., Bäckhed F., and Seeley R. J. (2014) FXR is a molecular target for the effects of vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Nature 509, 183–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McGavigan A. K., Garibay D., Henseler Z. M., Chen J., Bettaieb A., Haj F. G., Ley R. E., Chouinard M. L., and Cummings B. P. (2017) TGR5 contributes to glucoregulatory improvements after vertical sleeve gastrectomy in mice. Gut 66, 226–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Patti M. E., Houten S. M., Bianco A. C., Bernier R., Larsen P. R., Holst J. J., Badman M. K., Maratos-Flier E., Mun E. C., Pihlajamaki J., Auwerx J., and Goldfine A. B. (2009) Serum bile acids are higher in humans with prior gastric bypass: potential contribution to improved glucose and lipid metabolism. Obesity 17, 1671–1677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Simonen M., Dali-Youcef N., Kaminska D., Venesmaa S., Käkelä P., Pääkkönen M., Hallikainen M., Kolehmainen M., Uusitupa M., Moilanen L., Laakso M., Gylling H., Patti M. E., Auwerx J., and Pihlajamäki J. (2012) Conjugated bile acids associate with altered rates of glucose and lipid oxidation after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes. Surg. 22, 1473–1480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Baghdasaryan A., Claudel T., Gumhold J., Silbert D., Adorini L., Roda A., Vecchiotti S., Gonzalez F. J., Schoonjans K., Strazzabosco M., Fickert P., and Trauner M. (2011) Dual farnesoid X receptor/TGR5 agonist INT-767 reduces liver injury in the Mdr2−/− (Abcb4−/−) mouse cholangiopathy model by promoting biliary HCO output. Hepatology 54, 1303–1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vassileva G., Golovko A., Markowitz L., Abbondanzo S. J., Zeng M., Yang S., Hoos L., Tetzloff G., Levitan D., Murgolo N. J., Keane K., Davis H. R. Jr, Hedrick J., and Gustafson E. L. (2006) Targeted deletion of Gpbar1 protects mice from cholesterol gallstone formation. Biochem. J. 398, 423–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li F., Jiang C., Krausz K. W., Li Y., Albert I., Hao H., Fabre K. M., Mitchell J. B., Patterson A. D., and Gonzalez F. J. (2013) Microbiome remodelling leads to inhibition of intestinal farnesoid X receptor signalling and decreased obesity. Nat. Commun. 4, 2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brubaker P. L., Schloos J., and Drucker D. J. (1998) Regulation of glucagon-like peptide-1 synthesis and secretion in the GLUTag enteroendocrine cell line. Endocrinology 139, 4108–4114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li T., and Chiang J. Y. (2007) A novel role of transforming growth factor β1 in transcriptional repression of human cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase gene. Gastroenterology 133, 1660–1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]