Publisher's Note: There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

Key Points

Paris-Trousseau syndrome is solely a result of FLI1 hemizygous deletion, with ETS1 levels being normal.

Elevated FLI1 levels in megakaryocytes do not interfere with and may enhance megakaryopoiesis.

Abstract

Friend leukemia virus integration 1 (FLI1), a critical transcription factor (TF) during megakaryocyte differentiation, is among genes hemizygously deleted in Jacobsen syndrome, resulting in a macrothrombocytopenia termed Paris-Trousseau syndrome (PTSx). Recently, heterozygote human FLI1 mutations have been ascribed to cause thrombocytopenia. We studied induced-pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)–derived megakaryocytes (iMegs) to better understand these clinical disorders, beginning with iPSCs generated from a patient with PTSx and iPSCs from a control line with a targeted heterozygous FLI1 knockout (FLI1+/−). PTSx and FLI1+/− iMegs replicate many of the described megakaryocyte/platelet features, including a decrease in iMeg yield and fewer platelets released per iMeg. Platelets released in vivo from infusion of these iMegs had poor half-lives and functionality. We noted that the closely linked E26 transformation-specific proto-oncogene 1 (ETS1) is overexpressed in these FLI1-deficient iMegs, suggesting FLI1 negatively regulates ETS1 in megakaryopoiesis. Finally, we examined whether FLI1 overexpression would affect megakaryopoiesis and thrombopoiesis. We found increased yield of noninjured, in vitro iMeg yield and increased in vivo yield, half-life, and functionality of released platelets. These studies confirm FLI1 heterozygosity results in pleiotropic defects similar to those noted with other critical megakaryocyte-specific TFs; however, unlike those TFs, FLI1 overexpression improved yield and functionality.

Introduction

Transcription factors (TFs) are key regulators of gene expression. In hematopoiesis, TFs form a complex network regulating the fate of hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs). For example, in megakaryopoiesis, GATA-binding protein 1 (GATA1),1 its coactivator friend of GATA1 (FOG1),1 and runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1)2 form a complex with the E26 transformation-specific3 family of TFs that includes ETS proto-oncogene 1 (ETS1), GA-binding protein transcription factor α subunit (GABPA), and friend leukemia virus integration 1 (FLI1).4 In particular, FLI1 has been shown to be critical for late megakaryopoiesis,5 and its overexpression inhibits erythroid development,6,7 driving cell lines to develop megakaryocytic features.8

Jacobsen syndrome, an inherited autosomal deletion at chromosome 11q with its associated platelet defect, Paris-Trousseau syndrome (PTSx), was the first disease directly associated with FLI1 deletion.9 It should be noted that these patients all have the closely linked TF ETS1 also deleted10,11 (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site). Whether the described defect was a result of the heterozygous loss of 1 or both genes was unclear. A single report based on the study of primary marrow cells from 2 patients with PTSx concluded that the platelet disorder was caused by allelic-exclusion expression of FLI1.12 Recently, point mutations and amino acid substitutions in the DNA binding domain of FLI1 have been implicated as the probable cause of inherited thrombocytopenia in patients.3,13 Although these reports suggest FLI1 heterozygous exclusion may be an important cause of inherited thrombocytopenia, they did not detail the platelet defect or compare them with PTSx platelets.

Studies of GATA1 during megakaryopoiesis have suggested its overexpression may drive a megakaryocytic-like phenotype.14 However, continuous GATA1 overexpression with a lack of GATA1 modulation at specific stages of megakaryopoiesis may limit the ability of such megakaryocytes to undergo full maturation, leading to inefficient release of functional platelets. In contrast, co-overexpression of GATA1, FLI1, and T-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia 1 (TAL1) leads to a self-replicative cell line that released platelet-like particles in culture.15 Although the in vitro-released platelets showed some platelet-like features, these particles still had a shortened in vivo half-life in infused recipient mice, even with the depletion of particle-clearing mouse macrophages by pretreatment with clodronate liposomes.16

To further understand the role of FLI1 in megakaryopoiesis, we characterized megakaryocytes (iMegs) and platelets (iPlts) derived from human induced-pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). As seen with murine models of other TFs important in megakaryopoiesis (eg, RUNX117), mouse models have been of limited value, as Fli1+/− mice are unaffected, whereas Fli1−/− mice die at embryonic day 11.5 with thrombocytopenia and abnormal vasculature.10 We define the biology of PTSx and FLI1+/−-targeted deletion iMegs and their in vivo-released platelets, characterizing effects of FLI1 deficiency on megakaryopoiesis, thrombopoiesis, and platelet biology. We show that the FLI1 heterozygous loss alone explains the PTSx phenotype and is unlikely to involve allelic exclusion or ETS1 deficiency. Furthermore, we examined the effects of increased levels of FLI1 expression during megakaryopoiesis under the control of a Gp1ba promoter.18 Overexpression of FLI1 during terminal differentiation increased final iMeg yield and the quality of the iPlts released from these iMegs after being infused into recipient animals. The clinical implications of these findings are discussed.

Materials and methods

Generation, characterization, and differentiation of iPSC lines

A PTSx iPSC line was created at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Core from an affected patient (supplemental Table 1; supplemental Figure 1A), using reprogramming methodology as described.19,20 iPSC pluripotency characterization and isogenic cell line generation are described in further detail in supplemental Materials and methods.

Hematopoietic colony-forming assays and liquid expansion of HPCs to iMegs

Hematopoietic differentiation of iPSCs to HPCs was performed as described.21,22 HPCs were used in methylcellulose and megacult colony assays (Stem Cell Technologies, Inc) according to manufacturer instructions. Flow cytometry for CD41a and CD235a surface markers were used to determine purity and absolute number of HPCs. Expansion to iMegs was performed by plating 5 × 105 HPCs per 35-mm well in medium containing thrombopoietin and stem cell factor, as described.21 After 5 days, the quality and absolute number of iMegs were calculated from the percentage of cells expressing surface CD41a, CD42a, CD42b, and annexin V via flow cytometry.

Characterization of in vivo-generated platelets from infused iMegs

Male nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency/interferon receptor 2γ-deficient (NSG) mice (Jackson Laboratory) at 8 to 12 weeks of age were infused via tail vein with 1 to 2 × 107 iMegs suspended in 200 µL phosphate-buffered saline (calcium chloride and magnesium chloride free; Gibco). Isolated human platelets from healthy donors were similarly infused as a positive control. Retro-orbital blood collection was performed at various intervals postinfusion, and the human platelets and platelet-like particles were stained with anti-human CD41a antibody to distinguish them from the native murine platelets.23 Loss of the glycocalicin, an indicator of megakaryocyte injury,24 was measured using anti-human CD42a vs anti-human CD42b antibodies in addition to annexin V staining.

Baseline human platelet activation and responsiveness to agonist in isolated murine blood were assessed by surface P-selectin levels in the absence and presence of thrombin. NSG mice were infused as earlier, and ∼1 mL of whole blood was collected after 4 hours from the inferior vena cava. Washed platelets were isolated and resuspended into Tyrode’s buffer at pH 7.2, as described previously.25 Platelet activation with 1 U/mL thrombin (Sigma) was performed for 30 minutes at 37°C and then analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis.

Human platelet function was assessed using in situ cremaster arteriole laser injuries, as described.26 iMegs were prelabeled with 2 mM calcein AM (Invitrogen) for 30 minutes at 37°C, washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and resuspended in 200 µL phosphate-buffered saline before tail vein infusion into male NSG mice. To label mouse platelets, Alexa Fluor 647–labeled rat monoclonal anti-mouse CD41 Fab fragments (BD) were injected intravenously shortly before injury. Laser-induced injuries of cremaster arterioles were performed 4 hours after iMeg infusion. Human platelet incorporation was recorded by confocal microscopy and compared with the concurrent circulating percentage of human platelets in mouse blood.27

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way ANOVA, and data were reported as mean ± 1 standard error of the mean (SEM), using the GraphPad Prism software version 6.00 for Mac (GraphPad Software). Differences were considered significant when the P value was less than .05.

Study approval

Animal studies and human tissue sampling were done in accordance with CHOP’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Institutional Review Board, respectively.

Results

Establishment and characterization of iMegs with differing levels of FLI1

To determine whether the megakaryocyte/platelet defects observed in patients with PTSx are specifically a result of FLI1 expression levels, patient-specific and genome-edited iPSC lines were created (supplemental Table 2; supplemental Figure 1). Cells from a patient with Jacobsen syndrome and PTSx (supplemental Table 1) were used to create an iPSC line designated PTSx. A series of isogenic iPSC lines with increased or decreased levels of FLI1 were created from a control iPSC line, designated WT, that was used in a previous study of megakaryopoiesis.21 A heterozygous deletion of FLI1 (FLI1+/−) was created using TALEN nucleases (supplemental Figure 1C). Transgene overexpression of FLI1 was performed in the patient PTSx (PTSx-OE) and WT iPSC lines, using adeno-associated virus site 1 targeting of FLI1 driven by a Gp1ba promoter for megakaryocyte-specific expression21 (supplemental Figure 1D). WT lines overexpressing FLI1 transgene hemizygously and homozygously were designated WT-OE1 and WT-OE2, respectively.

The expected differences in FLI1 mRNA expression levels were confirmed in iMegs derived from these different lines (Figure 1A). During the 5-day expansion of HPCs to iMegs in the OE lines, FLI1 mRNA expression was increased compared with their respective parental lines. Although the Gp1ba promoter is a late megakaryocyte promoter, we have previously shown that it is also active in iPSC-derived progenitor cells.21 FLI1 mRNA expression in the PTSx and FLI1+/− lines started out at approximately half of WT on day 1, but gradually increased as differentiation progressed. FLI1 protein levels measured on day 5 of differentiation in the various lines were consistent with the genotypes of these lines (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Analysis of FLI1 mRNA and protein levels of FLI1, MPL, and PF4. Day 5 iMegs were selected for CD41a and analyzed using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and western blot. (A) Relative expression of FLI1 mRNA was performed using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction compared with WT. Mean ± 1 SEM are shown of 4 separate experiments. P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA. (B) Western blot analysis of FLI1. Relative expression was compared with WT. Means ± 1 SEM are shown for 4 separate experiments. P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of MPL. Relative surface MPL expression analyzed from 3 separate experiments using flow cytometry and 1-way ANOVA. (D) Similar to panel B, but measuring PF4.

In addition to FLI1, mRNA levels of TFs known to be important in megakaryopoiesis (ETS1, ETV6, and RUNX1) and several megakaryocyte-specific genes (MPL, MYH10, GP9, ITGA2B, and PF4) were also examined throughout the 5 days of iMeg expansion (supplemental Figure 2). After day 1, ETS1 levels were inversely related with the level of FLI1 in the developing megakaryocytes. ETS1 is physically close to FLI128 and is deleted along with FLI1 in PTSx. There has been speculation as to whether the PTSx phenotype is related to haploinsufficiency of ETS1, as well as FLI1.29 However, in spite of having only 1 copy of ETS1, PTSx megakaryocytes have an excess, not deficit, of ETS1 TF. Primary megakaryocyte ChIP-Seq data30 demonstrated a FLI1-binding site ∼100 kb downstream of ETS1 (supplemental Figure 3A). Markers of active enhancers, including H3K4me1 and H3K27ac,31 also localized to this site.32 This region was annotated by ChromHMM as “enhancer” chromatin in several cell types.33 Together, this pattern could indicate a regulatory mechanism by which FLI1 binding mediates suppression of ETS1 (supplemental Figure 3B).

The other TFs and megakaryocyte-specific proteins either correlated with or showed no clear relationship to FLI1 expression levels. A correlative relationship in mRNA levels was seen for ETV6 (supplemental Figure 2), another ETS family member whose haploinsufficiency also results in a quantitative platelet disorder.34 MPL mRNA levels also correlated with FLI1 mRNA levels (supplemental Figure 2). Surface MPL protein levels in iMegs at days 2 to 5 of differentiation (Figure 1C) were decreased in the FLI1+/− and PTSX lines, consistent with reports of decreased MPL after FLI1 mutation13 and of MPL as a direct target gene of FLI1.35 MYH10 transcript was increased during iMeg differentiation in the FLI1-low lines, reflecting reports of increased MYH10, silenced during normal megakaryocyte polyploidization and maturation,36 in PTSx patient platelets.3,13,37 Levels of PF4 protein were comparable in all lines (Figure 1D). Levels of RUNX1, GP9, ITGA2B, and PF4 transcripts were normal. GP9, ITGA2B, and PF4 have all been reported as direct targets of FLI1,5,35 but also are increased as a result of ETS1 overexpression during megakaryopoiesis.38 Perhaps the unexpectedly high ETS1 levels compensate for the decreased FLI1 levels.

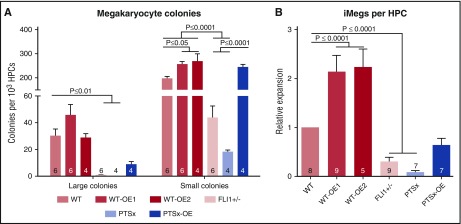

Effect of FLI1 on megakaryocyte and other lineage potential

To assess the effect of FLI1 on megakaryocyte clonogenic potential, a hematopoietic colony-forming assay in a collagen-based culture system39 was used to define the yield of large (≥50 cells) and small (<50 cells) megakaryocyte colony-forming units (CFU-MKs) (Figure 2A). Little to no large CFU-MKs were generated from PTSx and FLI1+/− progenitors, whereas the level of small CFU-MKs from these lines were ∼10% and ∼20% of WT, respectively. The WT-OE1 and WT-OE2 lines had more large CFU-MKs and significantly more small CFU-MKs compared with WT. These findings suggest that decreased expression of FLI1 affects megakaryocyte potential, especially large CFU-MK potential. Conversely, either the overexpression of FLI1 in both WT and PTSx lines increased the number of small CFU-MKs or the numbers were comparable to the parental lines. PTSx-OE large CFU-MKs were decreased compared with WT, but small CFU-MK numbers were comparable.

Figure 2.

Megacult colony assay and iMeg differentiation in liquid culture. (A) HPCs were plated in a semisolid Megacult colony system and analyzed at the end of the assay for colony count per input HPC. Means ± 1 SEM are shown along with the number of independent experiments performed. Significant P values performed using 1-way ANOVA are shown. (B) HPCs were grown in liquid culture and analyzed at the end of the assay for iMeg numbers. Relative expression to WT iPSC line is shown. Means ± 1 SEM are shown, along with the number of independent experiments performed. P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA.

The relative expansion of iMegs from HPCs in liquid culture was analyzed as another approach to study megakaryocyte development. The differentiation and expansion of HPCs to iMegs yielded results comparable to colony formation data (Figure 2B): The PTSx and FLI1+/− progenitors yielded fewer iMegs compared with WT. HPCs from the WT-OE1 and WT-OE2 lines yielded high expansion rates of ∼150% (P = .08) and ∼230% (P < .01), respectively, compared with WT. The PTSx-OE HPCs yielded more iMegs than parent PTSx HPCs, but to only 63% of WT.

The effect of FLI1 levels on myeloid and erythroid progenitor potential was also analyzed (supplemental Figure 4). Myeloid progenitor potential was comparable among all lines. The FLI1+/− progenitors resulted in more BFU-E and CFU-E colonies than WT progenitors, and the WT-OE lines resulted in decreased levels. Similarly, the PTSx progenitor resulted in more CFU-E colonies than PTSx-OE progenitors, although not when compared with WT progenitors. We believe this lack of difference between PTSx and WT progenitors may reflect differences between the genetic background of the individuals that contributed the WT and PTSx iPSCs or reflect the large genetic deletion in the PTSx cells. The BFU-E and CFU-E progenitor potential of WT-OE1, WT-OE2, and PTSx-OE HPCs were comparable or less than WT. These data support the known role of FLI1 driving the megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor toward the megakaryocyte lineage.6,7

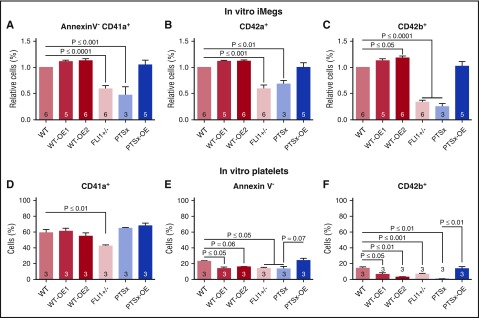

Qualitative characterization of the effects of FLI1 on iMegs

We next examined whether the iMegs obtained from the iPSC lines differed qualitatively as well as quantitatively. Flow cytometric analyses of megakaryocyte-specific surface markers were performed for CD41a (glycoprotein [GP] IIb/IIIa), an early marker of the megakaryocyte lineage40; CD42a (GPIX), a marker of megakaryocyte maturation41; and CD42b (GPIX/GPIbα), an indicator of megakaryocyte injury resulting from cleavage and removal of the extracellular glycocalicin domain of GPIbα.42 A lower percentage of PTSx and FLI1+/− iMegs expressed CD41a (Figure 3A), CD42a (Figure 3B), and CD42b (Figure 3C) compared with WT. A slightly higher percentage of WT-OE1 and WT-OE2 iMegs expressed CD41a, CD42a, and CD42b compared with WT, whereas PTSx-OE iMegs were comparable to WT. These data suggest that the maturation of PTSx and FLI1+/− iMegs may be impaired and corrected with FLI1 overexpression.

Figure 3.

Percentage of annexinV-CD41+CD42a+CD42b+ iMegs and in vitro–released platelets. Day 5 iMegs and released platelet-like particles were analyzed for surface markers, using flow cytometry. (A-C) iMegs were negative for annexin V and positive for CD41a, CD42a, and CD42b. (D-F) In vitro platelet-like particles positive for CD41a, negative for annexin V, and positive for CD42b. Means ± 1 SEM are shown with n = 3-6 independent experiments per arm. Significant P values were determined using 1-way ANOVA.

Previous studies from our group have shown that in vitro-released platelets have poor functionality and short half-lives as a result of faster clearance of CD42b− particles in the mouse circulation.23 In vitro-derived platelet particles, corresponding in size to human donor platelets, from iMeg cultures were analyzed for surface markers for CD41a, annexin V, and CD42b. Between 40% and 60% of the in vitro-derived platelet particles from all lines were CD41+, but low percentages are annexin V− (Figure 3E), suggesting many of the CD41+ particles may be activated or injured. The low percentage of CD42a+CD42b+ platelet particles supports that the vast majority (>85%) of in vitro platelet particles from all cell lines were injured, having CD42b cleaved (Figure 3F).

In addition to expressing megakaryocyte-specific surface markers, another indication of maturing megakaryocytes is nuclear endoreduplication.43 Overall, WT iMegs have low ploidy compared with bone marrow-mobilized CD34+-derived megakaryocytes.23 However, we saw a trend toward a decrease in 4N and >4N nuclei in the FLI1-low iMegs and an increase in 4N and >4N in WT-OE1 and WT-OE2 iMegs relative to WT iMegs (supplemental Figure 5).

As previously reported, up to 15% of PTSx platelets, but not bone marrow megakaryocytes, have fused, giant α granules on electron micrographs.9,44,45 Similar platelet giant granules were observed from a family with an autosomal recessive FLI1 mutation.13 Transmission electron microscopy images of 8 representative PTSx iMegs resulted in an average cell diameter less than WT, yet the difference did not reach significance. However, transmission electron microscopy images of FLI1+/− iMegs showed smaller cells compared with the WT iMegs (supplemental Table 4). The difference in findings between PTSx and FLI1+/− may be a result of the difference in genetic background of the individuals that contributed to the 2 iPSC lines, or they may reflect the large genetic deletion in the PTSx cells. The smaller FLI1+/− iMegs correlate with previous findings of increased micromegakaryocytes in PTSx patient bone marrow samples.9,44 Conversely, transmission electron microscopy micrographs of WT-OE2 iMegs contained larger cells, whereas the size of PTSx-OE iMegs were comparable to WT iMegs. Granules and open canalicular systems were observed in all samples, but no observable giant granules were found in either the PTSx or FLI1+/− iMegs (supplemental Figure 6).

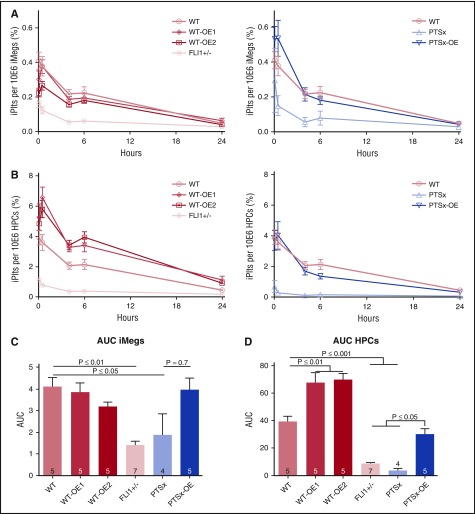

In vivo-released iPlts from infused iMegs in NSG mice

Because in vitro-generated platelet-like particles were only ∼50% platelets, and these were mostly injured, subsequent platelet analyses focus on in vivo-released platelet biology from iMegs. We have previously shown that infused human megakaryocytes, including iMegs, into immunodeficient NSG mice release iPlts intrapulmonarily, beginning almost immediately,23 similar to that seen endogenously in mice in which ∼50% of platelets are released from megakaryocytes entrapped in the lungs.46 These platelets have comparable size distribution, half-life, and functionality as donor-derived platelets, in contrast to in vitro-released platelet-like particles.23 iMegs of the various FLI1 lineages were infused into NSG mice, and the number and functionality of the released iPlts were measured. Released iPlts over the course of 24 hours were calculated as a percentage of human CD42b+ that, on forward scatter analysis, had a size range similar to that of infused human donor platelets. This value was normalized to the number of CD42b+ iMegs infused (Figure 4A), and separately to the number of HPCs needed to generate those iMegs (Figure 4B). Area under the curve of FLI1-low iPlts released was significantly less than WT per iMeg and per HPC, whereas PTSx-OE released the same number of platelets per iMeg and per HPC as WT (Figure 4C and D, respectively). WT-OE1 and WT-OE2 had the same area under the curve of released platelets per iMeg (Figure 4C), but an ∼50% increase per HPC (Figure 4D), consistent with their higher yield of iMegs per HPC (Figure 2B).

Figure 4.

In vivo iPlt generation is decreased for FLI1-low and increased for FLI1-high lines. (A,B) NSG mice were infused with iMegs, and percentage of human platelets was determined at various points up to 24 hours. Means ± 1 SEM are shown with 4-7 independent experiments per arm. (A, left) Data analyzed per infused iMegs generated from isogenic genome-edited iPSC lines. (Right) Data analyzed per infused iMegs WT iPSCs and the 2 PTSx lines. (B) Same as in panel A, but analyzed per initial HPCs from which the iMegs were prepared. (C-D) Area under the curve (AUC) calculations for iPlt generation either from iMegs (C) or from HPCs (D). Means ± 1 SEM are shown with number of independent experiments per arm shown in each bar. Significant P values were determined using 1-way ANOVA.

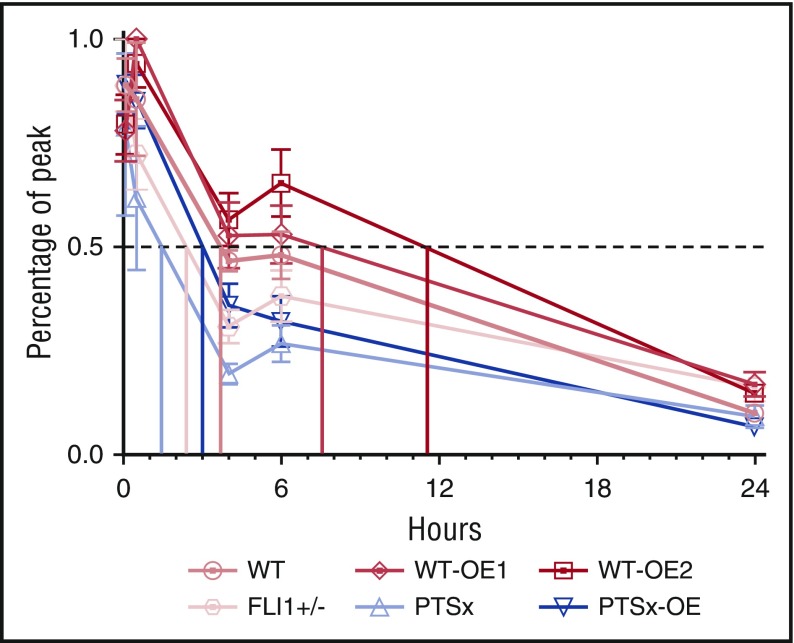

Calculated WT iPlt half-life was ∼4 hours, which was comparable to our previously published value23 (Figure 5). For the PTSx and FLI1+/− lines, iPlt half-lives were decreased to ∼1 and ∼2 hours, respectively. PTSx-OE iPlts had a half-life of ∼3 hours, comparable to WT-released platelets, whereas WT-OE1 and WT-OE2 iPlt half-lives were increased to ∼7 and ∼11 hours, respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

iPlt half-life is decreased for FLI1-low and increased for FLI1-overexpression lines. Percentage of peak iPlt generation up to 24 hours after iMeg infusion into NSG mice (n = 4-7 independent experiments, same as Figure 4A,D). Half-life is determined by the time at which there is 50% of iPlts compared with peak iPlt numbers.

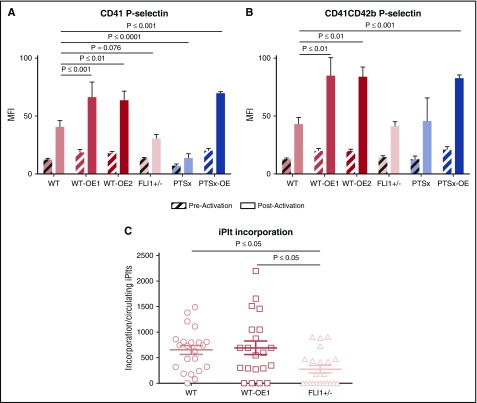

Released iPlt function

PTSx platelets have been reported to be dysfunctional as well as reduced in number.9,44,45 We asked what the effect was of FLI1 levels on platelet functionality in the released iPlts from the various FLI1-iMeg lines. Whole blood was drawn from NSG mice 4 hours after iMegs were infused and washed platelets isolated. These platelets were analyzed pre- and postactivation with thrombin via flow cytometry for surface P-selectin, a marker of platelet degranulation,47 and PAC-1 binding, an antibody for GPIIb/IIIa activation (Figure 6; supplemental Figure 7). Preactivation levels of P-selectin on CD41+ and CD41+CD42b+ iPlts were comparable across all lines, indicating that all iPlts were equally quiescent (Figure 6A and B, respectively). After thrombin activation, both FLI1-low CD41+ iPlt lines were hyporesponsive compared with WT iPlts, likely because a significant number of these iPlts were derived from injured iMegs (Figure 3C). The FLI1-low CD41+CD42b+ iPlts showed normal P-selectin levels postthrombin, indicating that uninjured FLI1-low iPlts retained responsiveness. The overexpressing lines all showed increased responsiveness to thrombin relative to WT iPlts. PAC-1 binding did not show relevant changes in responsiveness to thrombin, perhaps highlighting the different effects FLI1 levels have on distinct activation pathways in the iPLts (supplemental Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Ex vivo and in vivo functional analyses of iPlts. (A) CD41+ and (B) CD41+CD42b+ iPlt mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of surface P-selectin before and after thrombin stimulation of iPlts generated at 4 hours after iMeg infusion. Means ± 1 SEM are shown with n = 6 independent experiments per arm. Significance was determined by 1-way ANOVA. (C) Cremaster injuries were induced at 4 hours after iMeg infusion in NSG mice, and fluorescent images were recorded. The numbers reported are of human calcein AM–stained particles incorporated into a growing thrombus after normalization by dividing by the percentage of circulating CD42b+-human platelets as part of the total circulating platelets. Shown are the individual data point and mean ± 1 SEM of experiments from 4 individual mice with up to 6 injuries per mouse. Significance was determined by 1-way ANOVA.

We also assessed iPlt function in vivo by visualizing human platelet incorporation into laser-induced cremaster arteriolar injuries, as previously described.26 We compared iPlts from 3 lines: WT, WT-OE1, and FLI1+/− (Figure 6C). Data were consistent with the thrombin stimulation studies: Platelet incorporation into thrombi of FLI1+/− iPlts was decreased in comparison with WT, whereas the WT-OE1 iPlts had comparable incorporation as WT.

Discussion

These FLI1-modified iMeg studies provide new insights into the role of FLI1 during megakaryopoiesis, thrombopoiesis, and platelet biology. Murine models of Fli1-gene targeting have not replicated PTSx syndrome10 or the biology in the growing number of individuals with recognized FLI1 mutations and inherited thrombocytopenia.3 Although in vitro-generated iMegs do not fully replicate the biology of CD34-derived or primary megakaryocytes,23 we believe they offer the advantage of unlimited access to genetically modified iMegs that can be studied in parallel with control iPSC lines in which gene editing has been performed. In vivo-released iPlts from infused iMegs also allowed us additional characterization of platelets comparable to donor-derived platelets not possible by studies of in vitro-released platelet-like particles, of which only ∼60% are CD41+, and those that are positive are often CD42b− and bind annexin V, indicating they are injured and/or apoptotic.48

We demonstrate that PTSx iMegs, and iPlts replicated many of the known defects seen in this syndrome, beginning with a decrease in the number of iMegs derived per HPC and also decreased expression of megakaryocyte-specific markers. Moreover, we observed a redirection of HPCs toward the erythroid lineage, limiting the number of resulting iMegs. Furthermore, these studies show a clear defect in the ability to shed platelets relative to normal iMegs in vivo, with FLI1-low iPlts having decreased responsiveness to agonists and a decreased ability to be incorporated into a thrombus. Because PTSx is part of a larger syndrome associated with significant chromosomal deletion, it was not clear that all the defined defects were related to the deletion of FLI1.11,29 The following lines of evidence presented support that the megakaryocyte/platelet defects are predominantly a result of the FLI1 deficiency: megakaryocyte-specific overexpression of FLI1 in PTSx iMegs largely corrected the defects in megakaryopoiesis, thrombopoiesis, and platelet biology, even with a large 15.3-Mbp deletion on chromosome 11q; similar findings were observed for both the PTSx and FLI1+/− iMegs; and the TF ETS1, which is physically linked to FLI1,28 always deleted in PTSx,11,44 and important in megakaryopoiesis,38 is inversely regulated by FLI1. In the PTSx and FLI1+/− iMegs, the level of ETS1 is at least normal. There is no ETS1 TF deficiency in megakaryocytes from patients with PTSx.

Primary megakaryocytes isolated from 2 patients with PTSx had been described,12 and the results were consistent with these iMeg findings, but also raised the possibility that FLI1 expression undergoes monoallelic expression,12 in which half of the megakaryocytes coming from the missing FLI1 allele would be affected and the other half normal. We examined whether either PTSx or FLI1+/− HPCs transitioning to iMegs gave rise to distinct megakaryocytic populations consistent with allelic exclusion, but did not observe 2 populations. In a collagen-based culture system, PTSx iHPCs gave rise to virtually no large colonies (not just half as many as monoallelic exclusion would predict), and this was also seen with the FLI1+/− line (Figure 2A). The vast majority of PTSx iPlts also had a markedly shortened half-life rather than demonstrating 2 populations with distinct half-lives after infusion of the iMegs into NSG mice (Figure 5). Thus, if allelic exclusion of FLI1 expression had occurred, then the lower yield of iMegs per HPC, the lower yield of iPlts per iMeg, and the poor half-life of the FLI1-deficient iPlts compared with WT iPlts would mean that most platelets in a PTSx patient would be from the normal allele, and dysfunctional macrothrombocytes would be a considerable minority in patients, rather than dominating the patients’ platelet presentation.9,10,44,45

A prior study using megakaryocytes derived from the murine stem cell line G1ME suggested that continuous overexpression of TFs involved in megakaryopoiesis, such as GATA1, may harm overall megakaryocyte formation, thrombopoiesis, and platelet biology.14 We were, therefore, surprised to see that WT-OE1 and WT-OE2 lines underwent normal megakaryopoiesis, lost less CD42b from these iMegs than WT iMegs in vitro, and exhibited an extended iPlt half-life. The Gp1ba promoter is known to drive expression of a reporter gene during both hematopoiesis and megakaryopoiesis,21 and perhaps its temporal expression profile sufficiently coincides with that of FLI1 during normal human megakaryopoiesis. Alternatively, FLI1 overexpression during megakaryopoiesis may have fewer deleterious effects on megakaryocyte differentiation than continuous GATA1 overexpression, or overexpression of TFs during murine megakaryopoiesis may be more deleterious than in human megakaryopoiesis. Indeed, human megakaryocyte progenitors constitutively overexpressing GATA1, FLI1, and TAL1 differentiated into megakaryocytes that appeared functional.15 However, the in vivo biology of the released platelets was not rigorously tested, as the recipient immunodeficient mice were pretreated with clodronate liposomes, a technique that has previously been shown necessary to prolong the half-life of injured platelets.23 Also, whether FLI1 overexpression compensated for GATA1 overexpression, which allowed for normal megakaryopoiesis, was not addressed.

In summary, to further understand the role of FLI1 in megakaryocyte and platelet biology, we have studied iMegs derived from iPSCs generated from a patient with PTSx, as well as studies of FLI1 heterozygously disrupted in a WT iPSC line. We have also modified the WT and PTSx iPSC lines to overexpress FLI1 in a megakaryocyte-specific fashion. With the 2 FLI1 insufficient lines, we confirm the central role of heterozygous FLI1 loss in the megakaryocyte and platelet defects observed in PTSx and in patients with FLI1 heterozygous deficiency, and detail their qualitative and quantitative defects. We also demonstrate that FLI1 overexpression enhances megakaryopoiesis, thrombopoiesis, and platelet biology. Whether overexpression of FLI1 in in vitro-grown megakaryocytes can improve yield and functionality of platelets for clinical usage remains to be tested.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the Poncz laboratory for their thoughtful comments during the course of this work and the Human Hematopoietic Stem Cell Center of Excellence at CHOP for their training and assistance.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants T32HL007971 (K.K.V.), R01HL130698 (D.L.F. and M.P.), and U01HL099656 (D.L.F. and M.P.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: K.K.V. designed, performed, and evaluated the studies and prepared the manuscript; D.J.J. and R.B.L. assisted with iPSC studies and analyses, and V.H. with cremaster laser injury studies; C.S.T. analyzed the ETS1 binding region; D.J.J., S.K.S., and D.L.F. provided guidance and intellectual contribution to the manuscript; and M.P. provided overall project organization and direction, data interpretation, and manuscript preparation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mortimer Poncz, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, 3615 Civic Center Blvd, Abramson Research Center, Room 317, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: poncz@email.chop.edu.

References

- 1.Wang X, Crispino JD, Letting DL, Nakazawa M, Poncz M, Blobel GA. Control of megakaryocyte-specific gene expression by GATA-1 and FOG-1: role of Ets transcription factors. EMBO J. 2002;21(19):5225-5234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elagib KE, Racke FK, Mogass M, Khetawat R, Delehanty LL, Goldfarb AN. RUNX1 and GATA-1 coexpression and cooperation in megakaryocytic differentiation. Blood. 2003;101(11):4333-4341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stockley J, Morgan NV, Bem D, et al. ; UK Genotyping and Phenotyping of Platelets Study Group. Enrichment of FLI1 and RUNX1 mutations in families with excessive bleeding and platelet dense granule secretion defects. Blood. 2013;122(25):4090-4093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pang L, Xue HH, Szalai G, et al. . Maturation stage-specific regulation of megakaryopoiesis by pointed-domain Ets proteins. Blood. 2006;108(7):2198-2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackers P, Szalai G, Moussa O, Watson DK. Ets-dependent regulation of target gene expression during megakaryopoiesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(50):52183-52190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawada H, Ito T, Pharr PN, Spyropoulos DD, Watson DK, Ogawa M. Defective megakaryopoiesis and abnormal erythroid development in Fli-1 gene-targeted mice. Int J Hematol. 2001;73(4):463-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Athanasiou M, Mavrothalassitis G, Sun-Hoffman L, Blair DG. FLI-1 is a suppressor of erythroid differentiation in human hematopoietic cells. Leukemia. 2000;14(3):439-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Athanasiou M, Clausen PA, Mavrothalassitis GJ, Zhang XK, Watson DK, Blair DG. Increased expression of the ETS-related transcription factor FLI-1/ERGB correlates with and can induce the megakaryocytic phenotype. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7(11):1525-1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breton-Gorius J, Favier R, Guichard J, et al. . A new congenital dysmegakaryopoietic thrombocytopenia (Paris-Trousseau) associated with giant platelet alpha-granules and chromosome 11 deletion at 11q23. Blood. 1995;85(7):1805-1814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hart A, Melet F, Grossfeld P, et al. . Fli-1 is required for murine vascular and megakaryocytic development and is hemizygously deleted in patients with thrombocytopenia. Immunity. 2000;13(2):167-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grossfeld PD, Mattina T, Lai Z, et al. . The 11q terminal deletion disorder: a prospective study of 110 cases. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;129A(1):51-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raslova H, Komura E, Le Couédic JP, et al. . FLI1 monoallelic expression combined with its hemizygous loss underlies Paris-Trousseau/Jacobsen thrombopenia. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(1):77-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevenson WS, Rabbolini DJ, Beutler L, et al. . Paris-Trousseau thrombocytopenia is phenocopied by the autosomal recessive inheritance of a DNA-binding domain mutation in FLI1. Blood. 2015;126(17):2027-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noh JY, Gandre-Babbe S, Wang Y, et al. . Inducible Gata1 suppression expands megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors from embryonic stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(6):2369-2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreau T, Evans AL, Vasquez L, et al. . Large-scale production of megakaryocytes from human pluripotent stem cells by chemically defined forward programming. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Rooijen N, Hendrikx E. Liposomes for specific depletion of macrophages from organs and tissues. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;605:189-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Q, Stacy T, Binder M, Marin-Padilla M, Sharpe AH, Speck NA. Disruption of the Cbfa2 gene causes necrosis and hemorrhaging in the central nervous system and blocks definitive hematopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(8):3444-3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yarovoi HV, Kufrin D, Eslin DE, et al. . Factor VIII ectopically expressed in platelets: efficacy in hemophilia A treatment. Blood. 2003;102(12):4006-4013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. . Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861-872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mills JA, Wang K, Paluru P, et al. . Clonal genetic and hematopoietic heterogeneity among human-induced pluripotent stem cell lines. Blood. 2013;122(12):2047-2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sullivan SK, Mills JA, Koukouritaki SB, et al. . High-level transgene expression in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived megakaryocytes: correction of Glanzmann thrombasthenia. Blood. 2014;123(5):753-757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mills JA, Paluru P, Weiss MJ, Gadue P, French DL. Hematopoietic differentiation of pluripotent stem cells in culture. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1185:181-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Hayes V, Jarocha D, et al. . Comparative analysis of human ex vivo-generated platelets vs megakaryocyte-generated platelets in mice: a cautionary tale. Blood. 2015;125(23):3627-3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergmeier W, Burger PC, Piffath CL, et al. . Metalloproteinase inhibitors improve the recovery and hemostatic function of in vitro-aged or -injured mouse platelets. Blood. 2003;102(12):4229-4235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kowalska MA, Ratajczak MZ, Majka M, et al. . Stromal cell-derived factor-1 and macrophage-derived chemokine: 2 chemokines that activate platelets. Blood. 2000;96(1):50-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Celi A, Merrill-Skoloff G, Gross P, et al. . Thrombus formation: direct real-time observation and digital analysis of thrombus assembly in a living mouse by confocal and widefield intravital microscopy. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1(1):60-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuentes R, Wang Y, Hirsch J, et al. . Infusion of mature megakaryocytes into mice yields functional platelets. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(11):3917-3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, et al. . The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12(6):996-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carpinelli MR, Kruse EA, Arhatari BD, et al. . Mice Haploinsufficient for Ets1 and Fli1 Display Middle Ear Abnormalities and Model Aspects of Jacobsen Syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2015;185(7):1867-1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tijssen MR, Cvejic A, Joshi A, et al. . Genome-wide analysis of simultaneous GATA1/2, RUNX1, FLI1, and SCL binding in megakaryocytes identifies hematopoietic regulators. Dev Cell. 2011;20(5):597-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calo E, Wysocka J. Modification of enhancer chromatin: what, how, and why? Mol Cell. 2013;49(5):825-837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489(7414):57-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ernst J, Kheradpour P, Mikkelsen TS, et al. . Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature. 2011;473(7345):43-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noetzli L, Lo RW, Lee-Sherick AB, et al. . Germline mutations in ETV6 are associated with thrombocytopenia, red cell macrocytosis and predisposition to lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2015;47(5):535-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deveaux S, Filipe A, Lemarchandel V, Ghysdael J, Roméo PH, Mignotte V. Analysis of the thrombopoietin receptor (MPL) promoter implicates GATA and Ets proteins in the coregulation of megakaryocyte-specific genes. Blood. 1996;87(11):4678-4685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lordier L, Bluteau D, Jalil A, et al. . RUNX1-induced silencing of non-muscle myosin heavy chain IIB contributes to megakaryocyte polyploidization. Nat Commun. 2012;3:717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Antony-Debré I, Bluteau D, Itzykson R, et al. . MYH10 protein expression in platelets as a biomarker of RUNX1 and FLI1 alterations. Blood. 2012;120(13):2719-2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lulli V, Romania P, Morsilli O, et al. . Overexpression of Ets-1 in human hematopoietic progenitor cells blocks erythroid and promotes megakaryocytic differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13(7):1064-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hogge D, Fanning S, Bockhold K, et al. . Quantitation and characterization of human megakaryocyte colony-forming cells using a standardized serum-free agarose assay. Br J Haematol. 1997;96(4):790-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitjavila-Garcia MT, Cailleret M, Godin I, et al. . Expression of CD41 on hematopoietic progenitors derived from embryonic hematopoietic cells. Development. 2002;129(8):2003-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Debili N, Issaad C, Massé JM, et al. . Expression of CD34 and platelet glycoproteins during human megakaryocytic differentiation. Blood. 1992;80(12):3022-3035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robert A, Boyer L, Pineault N. Glycoprotein Ibα receptor instability is associated with loss of quality in platelets produced in culture. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20(3):379-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zimmet J, Ravid K. Polyploidy: occurrence in nature, mechanisms, and significance for the megakaryocyte-platelet system. Exp Hematol. 2000;28(1):3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Favier R, Jondeau K, Boutard P, et al. . Paris-Trousseau syndrome : clinical, hematological, molecular data of ten new cases. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90(5):893-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krishnamurti L, Neglia JP, Nagarajan R, et al. . Paris-Trousseau syndrome platelets in a child with Jacobsen’s syndrome. Am J Hematol. 2001;66(4):295-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lefrançais E, Ortiz-Muñoz G, Caudrillier A, et al. . The lung is a site of platelet biogenesis and a reservoir for haematopoietic progenitors. Nature. 2017;544(7648):105-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gremmel T, Koppensteiner R, Panzer S. Comparison of Aggregometry with Flow Cytometry for the Assessment of Agonists´-Induced Platelet Reactivity in Patients on Dual Antiplatelet Therapy. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sim X, Poncz M, Gadue P, French DL. Understanding platelet generation from megakaryocytes: implications for in vitro-derived platelets. Blood. 2016;127(10):1227-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]