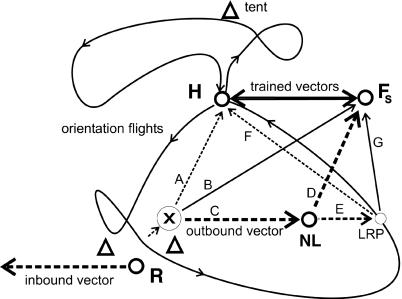

Fig. 4.

A model of the vector map. During observatory flights (curved lines with arrows), bees establish multiple associations between landmarks and the respective return headings and distances to the hive (dotted lines A and F). In addition, SF bees learn the heading and distance between the hive (H) and the feeder (Fs) (double-headed arrow labeled trained vectors). After being released at the release site (R) and applying the information about heading and distance from the feeder to the hive stored in working memory, bees search for a while. When SF bees find themselves at a location ( ) at which a particular heading and distance are retrieved (A), they may either follow this information and return to the hive or switch their motivation and aim for the feeder. In such a situation they retrieve the vector components (heading and distance) of the outbound route flight from the hive-feeder to the feeder (C), which leads them to a new location (NL), or they perform some form of large-scale vector integration that leads them along a novel route to the feeder (B). At the novel location NL they may apply the same vector integration (D) or reach another known place (LRP) from which they go through the same procedure, use the associated flight parameters (F) to fly back to the hive directly or perform vector integration (G). However, our data also are consistent with the possibility that bees establish during orientation flights a relational map-like memory. In that case, they would localize themselves according to local landmarks and views, and they would choose a flight vector to the localizations of the hive or the feeder.

) at which a particular heading and distance are retrieved (A), they may either follow this information and return to the hive or switch their motivation and aim for the feeder. In such a situation they retrieve the vector components (heading and distance) of the outbound route flight from the hive-feeder to the feeder (C), which leads them to a new location (NL), or they perform some form of large-scale vector integration that leads them along a novel route to the feeder (B). At the novel location NL they may apply the same vector integration (D) or reach another known place (LRP) from which they go through the same procedure, use the associated flight parameters (F) to fly back to the hive directly or perform vector integration (G). However, our data also are consistent with the possibility that bees establish during orientation flights a relational map-like memory. In that case, they would localize themselves according to local landmarks and views, and they would choose a flight vector to the localizations of the hive or the feeder.