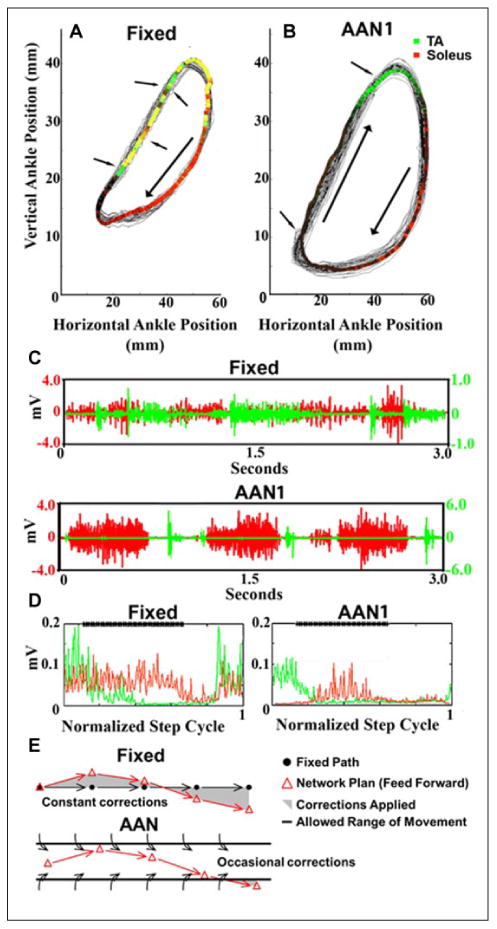

Figure 3.

(A) (Fixed) and (B) (assist-as-needed, AANI) show the ankle trajectories recorded over 30 seconds of stepping with the fixed trajectory and the AANI modes, respectively. The colored areas represent the average EMG activity recorded from the soleus and tibialis anterior (TA): red, soleus activity; green, TA activity; and yellow, soleus and TA co-activation. The arrows point to examples of changes in direction due to the robotic arm guiding the ankle toward the trajectory. (C) Raw EMG activity of the soleus and TA during 3 seconds of movement for each paradigm (top, Fixed; bottom, AANI). (D) The average integrated EMG for the soleus (red) and TA (green) from over 30 continuous seconds of stepping for each paradigm (left, Fixed; right, AANI). The bold line at the top of the box “****” marks the stance phase of the step cycle. (E) Schematic illustrating that in the fixed mode the progression of the movement defined by the robot from one time bin to the next time bin is predetermined, whereas the spinal networks will generate an activation pattern reflecting some probability of where the next point will be for each time bin (feed-forward). The shaded area represents the variation from that hypothetical difference between the effects compared to the AAN mode. Thus, in the fixed mode, the spinal networks are in a constant mode of the planned kinematics were constantly being corrected. Unlike the fixed mode, the window of tolerance for each time bin without being corrected in the AAN mode is sufficient to avoid continuous corrections during each time bin because the “window” allowed the planned kinematics to occur without interruption resulting in more effective learning of the stochastic phenomena intrinsic to networks (modified from Ziegler and others 2010).