Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: HIV testing, linkage in care, retention in care, youth

Abstract

Objective:

To determine the effectiveness of the Metropolitan Atlanta community adolescent rapid testing initiative (MACARTI) intervention relative to standard of care (SOC), in achieving early diagnosis, linkage, and retention among HIV-infected youth ages 18–24 years.

Design:

MACARTI was a pilot single-center, prospective, nonrandomized study.

Methods:

MACARTI combined nontraditional venue HIV testing, motivational interviewing, and case management. We collected demographic, clinical variables and calculated linkage and appointment adherence rates. We obtained SOC data from an adolescent HIV clinic. Longitudinal data were analyzed using inverse propensity treatment-weighted linear growth models; medians, interquartile ranges (IQR), means, and 95% confidence intervals are provided.

Results:

MACARTI screened 435 participants and identified 49 (11.3%) HIV infections. The SOC arm enrolled 49 new HIV-infected individuals. The 98 participants, (49 in each arm) were: 85% men; 91% Black; mean age = 21 years (SD : 1.8). Overall, 63% were linked within 3 months of diagnosis; linkage was higher for MACARTI compared to SOC (96 vs. 57%, P < 0.001). Median linkage time for MACARTI participants compared to SOC was 0.39 (IQR : 0.20–0.72) vs. 1.77 (IQR : 1.12–12.65) months (P < 0.001). MACARTI appointment adherence was higher than SOC (86.1 vs. 77.2%, P = 0.018). In weight-adjusted models, mean CD4+ T-cell counts increased and mean HIV-1 RNA levels decreased in both arms over 12 months, but the differences were more pronounced in the MACARTI arm.

Conclusion:

MACARTI successfully identified and linked HIV-infected youth in Atlanta, USA. MACARTI may serve as an effective linkage and care model for clinics serving HIV-infected youth.

Introduction

In 2015, Georgia had the fifth highest rate of new HIV diagnoses (12.9/100 000) in the United States; 66% of HIV-infected individuals lived in and 69% of new diagnoses were reported from Atlanta Metropolitan Statistical Area (Atlanta) in 2011 [1,2]. Gaps along the HIV care continuum among youth in Atlanta are evidenced by low rates of testing, linkage to care, and viral suppression. Among people living with diagnosed HIV in Georgia, only 68% of youth are linked to care within 30 days, and just 52 and 38% of 13–19 and 20–24 year olds, respectively, achieved viral suppression at last measurement [2]. Additionally, Atlanta youth are likely to be diagnosed at more advanced stages of illness with more 13–24 year olds progressing to Stage 2 HIV (CD4+ T cell count 200–499) at diagnosis compared with any other age group [3,4].

Youth living with HIV, have a higher prevalence of psychosocial stressors contributing to unfavorable clinical outcomes and broader gaps along the HIV continuum of care compared with HIV-infected adults [5–9]. Singer's et al.[10] syndemic theory suggests that health care is affected by multiple epidemics that should be addressed simultaneously. Adverse social structures such as poverty, discrimination, stigma, and psychiatric comorbidities (including depressive disorder, substance use) increase risk for HIV acquisition and adversely impact adherence to HIV treatment [11–13].

Effective interventions tailored to HIV-infected youth are urgently needed. Hall et al.[6] showed that only 62% of youth between 13 and 24 years were linked and 44% retained in care nationally. The Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health study documented that only 32.5% of youth achieved viral suppression [14], whereas a Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group study demonstrated a 6-month retention rate of 58% [15]. These studies underscore deficiencies in traditional approaches of HIV diagnosis and management for youth [16,17]. Newer, comprehensive approaches tailored for youth that address HIV diagnosis and management, including psychiatric comorbidities and psychosocial stressors may improve HIV outcomes.

Despite recommendations for routine HIV testing in healthcare settings [16], implementation gaps remain; especially in racial/ethnic minority youth [17]. Venue-based HIV testing can improve testing rates among youth. A study with young MSM, showed that factors associated with no previous HIV test included young age (13–24 years) and self-identifying as non-Hispanic black or Hispanic [18]. Alternate testing strategies have shown high positivity rates among those tested in nontraditional settings [19].

Motivational interviewing has been successful in the treatment of chronic diseases, [20,21]; however, data on motivational interviewing-based interventions in HIV-infected youth are limited [22]. A randomized trial in youth assessing the effectiveness of motivational interviewing delivered either by paraprofessional or professional staff showed improved retention in both arms with no differences between staff members delivering the intervention. However, preintervention data were incomplete for the majority of participants [23]. Another study used motivational interviewing and financial incentives with 11 perinatally infected youth with advanced immunosuppression; five achieved viral suppression at 1 year with a median CD4+ T cell count recovery of 140 cells/μl. This study was limited by small sample size and the potential confounding of financial incentives [24].

Case management has improved linkage/retention in care of HIV-infected individuals. The antiretroviral treatment access study (ARTAS) randomized recently diagnosed HIV-infected participants to a brief strength-based model of case management and care planning vs. usual care; 64% in the intervention arm were linked-to and retained-in care compared with 49% in the control arm [relative risk(adj) 1.41; P = 0.006]. ARTAS is recommended as an effective intervention by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [25–27]. However, 90% of ARTAS participants were over 26 years of age and youth was underrepresented [28].

Building on these studies, we developed the Metropolitan Atlanta community adolescent rapid testing initiative (MACARTI) a multipronged intervention combining nontraditional venue HIV testing, motivational interviewing, and case management support to improve diagnosis, linkage, and retention in care of youth ages 18–24 years. The intervention started with a formative phase of focus groups with HIV-infected and uninfected youth to inform a youth friendly strategy [29,30]. Motivational interviewing/case management approach was implemented through the first year postdiagnosis using a developmentally informed approach.

Our goals were to: increase opportunities for HIV testing and diagnosis for youth at places where they routinely gather, and strengthen HIV treatment and care for those living with HIV using the MACARTI intervention.

Methods

Study design

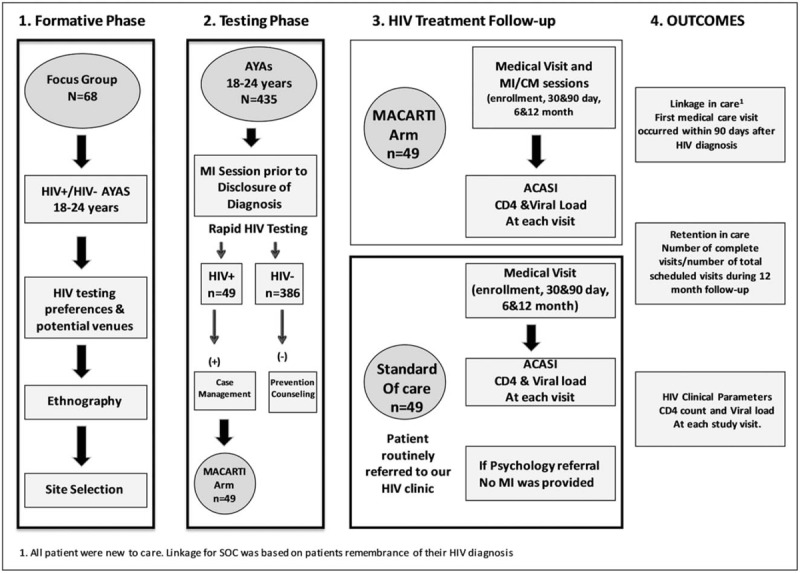

MACARTI was a pilot single-center, prospective, nonrandomized interventional study of HIV-infected youth. Enrollment occurred from December 2012 through January 2015, with follow-up through February 2016. The MACARTI trial flow (Fig. 1) is described briefly below. The Emory Institutional Review Board, the Grady Research Oversight Committee, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Center for HIV, viral hepatitis, Sexually Transmitted Disease, and Tuberculosis prevention approved this study. All participants provided written informed consent.

Fig. 1.

The MACARTI trial flow diagram.

ACASI, audio computer-assisted self-interview; CM, case management; MACARTI, Metropolitan Atlanta community adolescent rapid testing initiative; MI, motivational interviewing.

Formative phase and venue testing selection

We conducted focus groups with 68 HIV-infected and uninfected youth to understand testing preferences and potential venues for testing. In total, 17 focus groups (11 with HIV-infected, two with HIV-uninfected, and four with a mixed group of HIV-infected and uninfected youth) were conducted (four participants/group). Their responses were used to develop a youth friendly testing strategy, to select testing sites, and to better characterize postdiagnosis support. Following the focus groups, we conducted ethnographic observations of prospective venues to inform site selection [30]. Venues were selected only if they provided a private space for testing.

Testing phase

Study team

The MACARTI study staff implementing the intervention included: a physician (study Principal Investigator-A.F.C-G), a psychology fellow (K.F.), one case manager, and three recruiters/testers. Community partners (AID Atlanta, AIDS Healthcare Foundation, and Positive Impact) also provided personnel during testing events as needed. Study personnel had no previous motivational interviewing experience and received training by the study psychologist and/or fellow (K.F. or C.G.), utilizing a motivational interviewing group facilitator manual with motivational interviewing information, motivational interviewing techniques, and motivational activities. Study staff learned theoretical and practical applications of motivational interviewing, including how to apply reflectively listening and ask open-ended questions, assess levels of motivation and confidence, and elicit barriers to adherence, confidence, and commitment language [31].

Participants

Participants in the testing phase included youth ages 18–24 years. The intervention arm (MACARTI) included youth diagnosed with HIV at nontraditional venues by either the study team or a community partner. The standard of care (SOC) arm included participants ages 18–24 years referred to the Ponce Family and Youth Clinic (PFYC) of Grady Health Systems for HIV care. Participants from both arms were selected only if they had a previously negative or unknown HIV test.

Metropolitan Atlanta community adolescent rapid testing initiative arm enrollment procedures

Members of the study team (at least one recruiter and one tester) conducted testing in venues selected during the formative phase. For participants who agreed to be tested, testing was performed using a 60 seconds INSTI HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody test (Biolytical Laboratories, Inc, Richmond, British Columbia, Canada; sensitivity and specificity of 99.8 and 99.5%, respectively) [32]. The tester conducted a motivational interviewing/case management session prior to disclosure of diagnosis. Motivational interviewing/case management was used prior to disclosure to address potential ambivalence toward seeking HIV-related care and to generate a plan of action to either improve clinical outcomes (if test was positive) or to establish HIV prevention strategies (if test was negative). HIV-infected patients were given instructions on how to get to the PFYC and provided information about documents needed for enrollment into medical care. After the diagnosis was made, study personnel maintained contact and assisted with clinic enrollment. At the initial medical visit, each participant had his or her blood drawn for HIV-1 RNA [Viral load (VL)] and CD4+ T-cell count. Participants had a motivational interviewing session with the psychology fellow to continue addressing potential ambivalence toward follow-up care with follow-up visits at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. All participants received reminder calls the day prior to their study visits and for rescheduling purposes if the visit was missed. If participants stopped attending visits or answering phone calls from the study team, they were considered lost to follow-up, triggering a referral to the health department for tracking purposes. Participants also had the option to enroll in another HIV clinic (this was requested by two participants); we then helped these participants arrange appropriate follow-up. Participants enrolled at a non-PFYC site were asked if they wished to continue in the study. If they did, a signed release of medical records was required and the same number of visits occurred with study personnel travelling to their preferred clinic to deliver the intervention. No significant differences were noted with the delivery of the intervention at the non-PFYC sites.

Standard of care participants

SOC participants were newly HIV-diagnosed youth referred for care to the PFYC through conventional referrals from other agencies, hospitals, or medical providers. The PFYC policy is to try to link patients within 72 h after referral; therefore, confounding from the referral process/scheduling was not a concern. SOC participants received standard support services upon request including psychological and case management support. SOC psychological support met practice standards and case management support was limited to providing referrals for housing, food stamps, and transportation as needed. SOC participants also received reminder calls prior to each appointment for rescheduling purposes from PFYC personnel.

Data collection

Once consented, participants from both arms completed baseline audio computer-assisted self-interview questionnaires. Data collected included demographic information, employment, education, drug use, and sexual history. Clinical information was obtained from the medical records and included baseline and follow-up CD4+ T cell count, VL, any antiretroviral therapy prescriptions, any AIDS-defining diagnoses, and condom use at last sexual encounter. Baseline and follow-up questionnaires were obtained at screening, enrollment, at 30 and 90 days, and at 6 and 12 months.

Metropolitan Atlanta community adolescent rapid testing initiative intervention components

Motivational interviewing

A detailed description of the motivational interviewing component of the intervention is presented in Appendix I, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B93. Briefly, motivational interviewing is an evidence-based therapeutic approach. Treatment fidelity depends upon the provider's adherence to the ‘spirit’ of the approach (namely, partnership, acceptance, compassion, and evocation), which can be reliably measured (see quality and fidelity section below) as opposed to adherence to specific guidelines [20,31,33–35]. Motivational interviewing focuses on strengths and self-efficacy, whereas emphasizing collaboration, empowerment, respect for choice, and understanding of the participant's perspective [33]. MACARTI participants received motivational interviewing sessions at the venue before disclosure of HIV diagnosis, and at all study visits.

Strength-based model of case management

A strength-based model of case management was employed to empower the client, build self-esteem, and enable the participants’ utilization of available resources. This model provides care that is beyond accessing services; it empowers participants to identify their own needs in utilizing available resources and services. Case management was provided at each study visit for the MACARTI arm participants. Problem-solving, goal planning, and guidance counseling were used to help participants with concerns identified by case management. An average meeting for case management lasted approximately 45–60 min.

Quality and fidelity

A standard operating procedure manual was developed and available to study staff, ensuring quality and fidelity to study procedures. To evaluate fidelity to the motivational interviewing protocol, the motivational interviewing trainer assessed 20% of the sessions for consistent use of motivational interviewing techniques and retrained staff if deviations were noted.

Definitions

Linkage to care: the first medical care visit occurred within 90 days after HIV diagnosis.

Retention in care: number of completed visits divided by the number of total scheduled visits during the 12-month follow-up [36], among participants who attended at least one medical care visit. Individuals who never linked (4/98; 4%) were not counted in retention in care calculations.

Viral suppression: number of participants who had a VL of less than 40 copies/ml at the 1-year study visit, among participants who completed the study.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (Cary, North Carolina, USA) and CRAN R v.3.3 (Vienna, Austria), and significance was evaluated two-sided at the 0.05 level. Demographic, drug use, sexual history, and clinical characteristics were summarized overall and by SOC and MACARTI arms using means and standard deviations, medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), or frequencies and percentages as appropriate. Two-sample testing, including both parametric (t-tests and χ2tests) and nonparametric (Wilcoxon and Fisher's) approaches were used to gauge dissimilarities across the study groups at baseline. Differences in visit attendance, retention, and linkage between SOC and MACARTI arms were similarly considered. Owing to noted baseline covariate differences across SOC and MACARTI arms, an inverse propensity treatment-weighted (IPTW) score was calculated using binary logistic regression and added as an observation weight characteristic to the sample, to control for baseline study arm disparities.

Linear mixed-effects growth models were used to evaluate statistical differences over study visit follow-up in CD4+ T cell count and VL between the SOC and MACARTI arms. The fixed effect for each model was treatment arm (2 levels), and the random effects were participant-specific intercepts and study visit slopes. Interactions between treatment arm and study visit were included, and because of curve-linear associations in the raw data, quadratic terms were added to each model for study visit. For CD4+ T cell count, a square-root transformation was applied to the outcome; for VL, both the outcome values and study visit were natural-log transformed. All observations in the mixed-effects regression models were evaluated unweighted and weighted using the IPTW score. All presented results have been back transformed to their original units, and results are given as least-squares mean estimates with associated 95% confidence intervals (CI). Further details for the propensity and linear growth models are provided in Appendix II, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B93.

Results

We tested 435 participants and identified 49 as HIV infected, for a positivity rate of 11.3%. Multiple sites were used for testing; however, the highest positivity rate was seen in nightclubs (30%) and street testing in areas identified as high risk by ethnographic studies (18%; Table 1). The SOC arm screened 62 participants to enroll 49 HIV-infected individuals new to HIV care; 13 were excluded because they were not new to HIV care. In total, 98 participants, 49 in each arm, were enrolled; 85% men; 91% Black; mean age was 21 years (SD : 1.8 years); 78% identified as homosexual/bisexual or queer; 62% had high school education or less; 23% percentage reported currently using drugs (marijuana, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamines, ecstasy, inhalant, or other); 14% reported a history of abuse (Table 2). After IPTW adjustment, all differences were balanced between MACARTI arm and SOC participants (Table 2), per a weighted standardized difference cutoff of 0.25.

Table 1.

Testing venues and positivity rate. The Metropolitan Atlanta community adolescent rapid testing initiative trial, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 2012–2016.

| Venue type | Number tested | Identified positives | Positivity rate |

| Night clubs | 122 | 37 | 30% |

| College campus | 98 | 5 | 5% |

| Street testinga | 38 | 7 | 18% |

| Private parties | 19 | 0 | 0% |

| Pride events | 38 | 0 | 0% |

| Malls and surroundings | 6 | 0 | 0% |

| Fairs | 19 | 0 | 0% |

| Shelters | 95 | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 435 | 49 |

aPreviously determined high risk areas by ethnographic studies.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics for standard of care and intervention participants, the MACARTI Trial, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 2012–2016.

| Characteristic, N (%) | Overall N = 98 | SOC N = 49 | MACARTI N = 49 | P value | Unweighted standard difference | Weighted standard differencea |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 83 (84.7%) | 36 (73.5%) | 47 (95.9%) | 0.004 | 0.656 | 0.097 |

| women | 15 (15.3%) | 13 (26.5%) | 2 (4.1%) | |||

| Race | ||||||

| Black | 89 (90.8%) | 47 (95.9%) | 42 (85.7%) | 0.159 | 0.359 | 0.230 |

| Other (white, Hispanic, other) | 9 (9.2%) | 2 (4.1%) | 7 (14.3%) | |||

| Age (year), mean ± SD | 21.5 ± 1.8 | 21.3 ± 1.8 | 21.7 ± 1.7 | 0.175 | 0.276 | 0.083 |

| Work status | ||||||

| Employed/in school | 74 (75.5%) | 32 (65.3%) | 42 (85.7%) | 0.019 | 0.489 | 0.139 |

| Neither | 24 (24.5%) | 17 (34.7%) | 7 (14.3%) | |||

| Education, N = 97 | ||||||

| High school or less | 60 (61.9%) | 35 (72.9%) | 25 (51%) | 0.026 | 0.463 | 0.154 |

| College or more | 37 (38.1%) | 13 (27.1%) | 24 (49%) | |||

| Ever abused alcohol | 15 (15.3%) | 3 (6.1%) | 12 (24.5%) | 0.022 | 0.528 | 0.083 |

| Currently using drugs | 22 (22.5%) | 9 (18.4%) | 13 (26.5%) | 0.333 | 0.197 | 0.008 |

| Abused type | ||||||

| No abuse | 84 (85.7%) | 42 (85.7%) | 42 (85.7%) | 1.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Abused | 14 (14.3%) | 7 (14.3%) | 7 (14.3%) | |||

| Sexual orientation | ||||||

| Straight | 22 (22.5%) | 19 (38.8%) | 3 (6.1%) | <0.001 | 0.850 | 0.198 |

| Gay/bisexual/queer | 76 (77.5%) | 30 (61.2%) | 46 (93.9%) | |||

| Condom usage | ||||||

| Always/usually | 71 (72.5%) | 33 (67.4%) | 38 (77.6%) | 0.258 | 0.230 | 0.249 |

| Sometimes/never | 27 (27.5%) | 16 (32.6%) | 11 (22.4%) | |||

| Ever had STIb – patient report, N = 97 | 47 (48.5%) | 28 (57.1%) | 19 (39.6%) | 0.084 | 0.357 | 0.071 |

| Any AIDS defining conditions, N = 94 | 34 (36.2%) | 25 (51%) | 9 (20%) | 0.002 | 0.685 | 0.112 |

MACARTI, Metropolitan Atlanta community adolescent rapid testing initiative; SOC, standard of care.

aBaseline propensity balancing results are presented in the supplemental materials; a cutoff of <0.25 was utilized to indicate covariate balance.

bSexually transmitted infection.

Baseline HIV characteristics

Compared to SOC, MACARTI arm participants reported fewer AIDS-defining conditions (20 vs. 51%, P = 0.002) and a higher mean CD4+ T cell count [317 (IQR : 218–512) vs. 196.5 (IQR : 61–377.5) cells/μl, P = 0.007].

Linkage to care

Overall, 63% of participants were linked to care within 90 days of diagnosis; however, linkage was higher for the MACARTI arm compared to SOC (88 vs. 39%, P < 0.001). Weighted, MACARTI linkage remained higher than SOC (96 vs. 57%, P < 0.001). Weighted median linkage time for MACARTI participants compared to SOC was 0.39 (IQR : 0.20–0.72) vs. 1.77 (IQR : 1.12–12.65) months (P < 0.001). An IPTW-adjusted multivariable logistic model showed that MACARTI participants had significantly higher odds of linking within 90 days than those in SOC arm (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 18.17, 95% CI : 3.27–100.90).

Retention in care

MACARTI arm participants had better appointment adherence compared to SOC participants (86.1 vs. 77.2%, P = 0.018). MACARTI participants also had better adherence throughout each of the follow-up study visits, albeit only significant at 90 days (Table 3). We also looked at the percentage of participants who attended 80 and 100% of clinical visits scheduled. Although there was no statistical difference at 80% of scheduled visits, 50% of MACARTI participants attended 100% of the visits compared to 26% in the SOC arm (P = 0.017).

Table 3.

Proportion of appointment adherence stratified by study arm, the Metropolitan Atlanta community adolescent rapid testing initiative trial, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 2012–2016.

| Visit, n/N (%) | Standard arm appointment adherence | MACARTI arm appointment adherence | P value |

| Unweighted | |||

| 30 days | 35/49 (71.4%) | 38/45 (84.4%) | 0.130 |

| 90 days | 37/49 (75.5%) | 43/45 (95.6%) | 0.008 |

| 6 months | 30/49 (61.2%) | 34/45 (75.6%) | 0.137 |

| 12 months | 30/49 (61.2%) | 33/45 (73.3%) | 0.212 |

| Overall | 181/245 (73.9%) | 197/229 (86%) | 0.001 |

| Weighted | |||

| 30 days | 42.6/52.7 (80.8%) | 30/37.8 (79.3%) | 0.864 |

| 90 days | 36.8/52.7 (69.9%) | 36.1/37.8 (95.6%) | 0.002 |

| 6 months | 32.4/52.7 (61.5%) | 29.1/37.8 (77%) | 0.119 |

| 12 months | 39/52.7 (74%) | 29.8/37.8 (78.8%) | 0.603 |

| Overall | 203.6/263.6 (77.2%) | 162.7/188.9 (86.1%) | 0.018 |

MACARTI, Metropolitan Atlanta community adolescent rapid testing initiative.

CD4+ T cell count and HIV-1 RNA levels

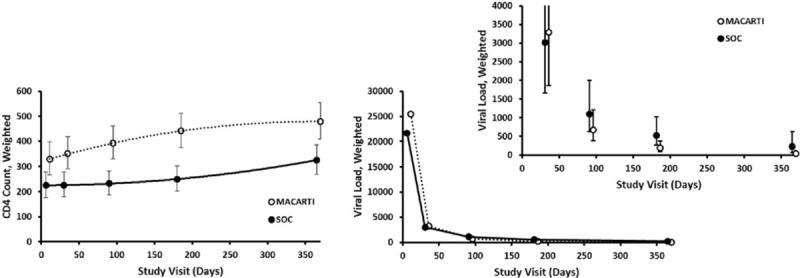

CD4+ T cell counts increased significantly within both arms. Growth model estimates indicated MACARTI and SOC participants gained 149 and 101 cells/μl, respectively, at 12 months. Additionally, CD4+ T cell counts in the MACARTI arm were significantly higher at all study visits relative to the SOC arm (Appendix II-Table 3b, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B93). The growth trajectory in CD4+ T cell count over participant follow-up was significantly higher in the MACARTI arm relative to the SOC (P = 0.004) (Fig. 2; Appendix II-Table 3a, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B93). Growth model estimates for VL indicated significant decreases in both arms, and although the overall growth trajectories were not significantly different between the two arms (P = 0.1) (Fig. 2; Appendix II-Table 4a, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B93), MACARTI arm participants had significantly lower VL at 6 months (P = 0.031) and 1 year (P = 0.008), respectively (Appendix II-Table 4b, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B93). At 1 year, the weighted percentage of participants in the MACARTI arm who had an undetectable VL was 83% compared to 41% in SOC arm (P < 0.001); concurrently, the odds of having an undetectable VL at 1 year was significantly higher in MACARTI compared to the SOC arm (aOR = 6.80, 95% CI : 2.09–22.15, P = 0.002).

Fig. 2.

Model-based change in CD4+ T cell count and viral load overtime by treatment arm – mean estimates and 95% confidence intervals, The MACARTI Trial, Atlanta, GA, 2012–2016.

Discussion

The MACARTI intervention successfully identified HIV-infected youth in the community, linking them to HIV care within 90 days of diagnosis and achieving high retention rates consistent with national HIV/AIDS strategy goals [37]. Factors such as psychological distress, fear, lack of information, traumatic experiences, and lack of food, transport and housing, create syndemics of risk and add complexity to the care of HIV-infected youth [38]. MACARTI utilized motivational interviewing and case management to address behavioral, motivational, and socioeconomic factors that affect HIV care. In MACARTI, motivational interviewing started in the venue prior to disclosure of the diagnosis to build rapport, prepare participants emotionally in the event of a positive HIV test, and to enable participants to develop a plan of action proactively, regardless of the test result. After linkage, motivational interviewing promoted achievement of: attending medical visits, initiating and adhering to antiretroviral therapy, and achieving viral suppression.

MACARTI identified high-risk youth, validating our formative work and targeted testing strategy. Strategies designed without youth input may not be able to access this hard-to-reach population, underscoring the importance of developing youth-oriented, culturally competent interventions. MACARTI also enabled diagnosing youth at earlier stages of HIV disease compared with participants in the SOC arm. Early diagnosis and treatment of HIV has significant individual and public health advantages, including increased survival and decreased secondary transmission [39,40]. Interventions incorporating enhanced testing, linkage, and retention components can reduce HIV incidence by 54% and mortality rate by 64%; these outcomes are cost-effective compared to no intervention [41].

Although MACARTI was not powered to look at differences in HIV clinical parameters, we noted decreases in VL and increases in CD4+ T cell count in both arms. The CD4+ T cell count trend over time was significantly better for the MACARTI than the SOC arm participants. VL was lower at all time points for MACARTI arm participants; however, statistical significance was reached during the latter part of the follow-up period suggesting that youth-informed interventions, such as MACARTI, provide additional support time points beyond the first few months’ postdiagnosis. This type of intervention may seem more labor intensive and challenging for broader implementation purposes; however, the psychosocial needs of youth may require such interventions to achieve the desired HIV continuum of care goals in this population.

The study has several limitations. First, the study population reflected a convenience sample that was not identified randomly, and the study was conducted in a single site. Although results may not be generalizable, the HIV epidemiology in Georgia reflects the current US epidemic [1]. Additionally, as the PFYC is the only adolescent HIV clinic in Georgia, we potentially accessed the majority of HIV-infected youth in Atlanta. Second, several differences in baseline characteristics were noted between groups. Some of these differences may be related to the venue selection process (not all potential venues where chosen as we required specific standards for testing confidentially and privacy), which may have shifted the MACARTI population toward a more employed/educated population that could afford entrance to specific sites. Additionally, as the intervention included targeted testing based on our formative phase results and positivity rates obtained in the different venues, we could have inadvertently oversampled the gay/bisexual population. However, the use of IPTW balanced both groups, which allowed us to control for differences in baseline characteristics during the analysis. Third, for the linear growth models, missing data were handled under a mixed-model framework, allowing for incomplete observations in the analysis. For all other analyses, complete case data were used, and missing observations were removed. Concurrent with the mixed-model framework, missing data were assumed to be at random after visual evaluation of the participation logs for patterns in attrition, as well as quantitative analyses considering univariate differences in the baseline covariates between those that attended their study visits vs. those that did not. Although we feel missing at random is an appropriate assumption for our data, we acknowledge that some missing data may not be random. Fourth, although we found significant differences in CD4+ T cell count and VL trends, which suggests improved immunologic recovery and viral control in the MACARTI arm, our sample sizes were small; larger studies are warranted to confirm this finding.

In conclusion, despite the need of a larger randomized control study to further test this intervention, the results of the MACARTI trial are very promising and suggest that the combination of nontraditional venue testing, motivational interviewing, and case management has the potential to effectively decrease gaps for youth along the HIV care continuum.

Acknowledgements

The authors will like to acknowledge our community partners AIDS Healthcare Foundation, AID Atlanta and Positive Impact, the Fulton County Department of Health and Wellness and the LGTBQ unit of the Atlanta Police Department.

A.F.C-G contributed in conception and design of the work; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, manuscript preparation, revision and submission of final manuscript. S.E.G., statistical analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation and revision. L.T-S: Data acquisition, and interpretation, manuscript revision. K.F., data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, manuscript revision. S.A.H., analysis, and interpretation of data, manuscript revision. A.M., analysis, and interpretation of data, manuscript revision. Z.G., analysis, and interpretation of data, manuscript revision. T.L., design of the work, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript revision. C.G., design of the work, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript revision. M.Y.S., design of the work, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript revision. R.C., conception and design of the work; manuscript preparation, manuscript revision.

All authors reviewed the final submitted manuscript and gave their approval. All authors are in agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

These data were presented in part at the National HIV Prevention Conference, Atlanta, Georgia, December 2015 and at the Conference of Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle Washington, February 2017.

The work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, grant number 5U01PS003322, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award number UL1TR000454 and by the Center for AIDS Research At Emory University (P30AI050409).

A.F.C.-G. has received research support from Gilead and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. R.C. has received research support from Gilead.

The findings and conclusions in the paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Website (http://www.AIDSonline.com).

References

- 1.The Georgia Department of Public Health, HIV Surveillance Fact Sheet, 2014. Accessed at https://dph.georgia.gov/sites/dph.georgia.gov/files/HIV_EPI_Fact%20Sheet_Surveillance_2014.pdf [Accessed 18 December 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Georgia Department of Public Health, HIV Care Continuum Report, Georgia, 2014. Accessed at https://dph.georgia.gov/sites/dph.georgia.gov/files/HIV%20Care%20Continuum%20Georgia%202014_07%2007%2016_final.pdf [Accessed 18 December 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.HIV Surveillance Update. Online: Georgia Department of Public Health Epidemiology; 22 July 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIVincidence among young men who have sex with men: seven U.S. cities, 1994-2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001; 50:440–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Philbin MM, Tanner AE, DuVal A, Ellen JM, Xu J, Kapogiannis B, et al. Factors affecting linkage to care and engagement in care for newly diagnosed HIV-positive adolescents within fifteen adolescent medicine clinics in the United States. AIDS Behav 2014; 18:1501–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall HI, Gray KM, Tang T, Li J, Shouse L, Mermin J. Retention in care of adults and adolescents living with HIV in 13 U.S. areas. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 60:77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minniear TD, Gaur AH, Thridandapani A, Sinnock C, Tolley EA, Flynn PM. Delayed entry into and failure to remain in HIV care among HIV-infected adolescents. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2013; 29:99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryscavage P, Anderson EJ, Sutton SH, Reddy S, Taiwo B. Clinical outcomes of adolescents and young adults in adult HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011; 58:193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuhns LM, Hotton AL, Garofalo R, Muldoon AL, Jaffe K, Bouris A, et al. An index of multiple psychosocial, syndemic conditions is associated with antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2016; 30:185–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singer MC, Erickson PI, Badiane L, Diaz R, Ortiz D, Abraham T, et al. Syndemics, sex and the city: understanding sexually transmitted diseases in social and cultural context. Soc Sci Med 2006; 63:2010–2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oldenburg CE, Perez-Brumer AG, Reisner SL. Poverty matters: contextualizing the syndemic condition of psychological factors and newly diagnosed HIV infection in the United States. AIDS 2014; 28:2763–2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and public health: reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Med Anthropol Q 2003; 17:423–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo X, Liu G, Frush K, Hey LA. Children's health insurance status and emergency department utilization in the United States. Pediatrics 2003; 112:314–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding H, Wilson CM, Modjarrad K, McGwin G, Jr, Tang J, Vermund SH. Predictors of suboptimal virologic response to highly active antiretroviral therapy among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adolescents: analyses of the reaching for excellence in adolescent care and health (REACH) project. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009; 163:1100–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudy BJ, Lindsey JC, Flynn PM, Bosch RJ, Wilson CM, Hughes ME, et al. Pediatric Aids Clinical Trials Group 381 Study Team. Immune reconstitution and predictors of virologic failure in adolescents infected through risk behaviors and initiating HAART: week 60 results from the PACTG 381 cohort. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2006; 22:213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006; 55:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Millett GA, Ding H, Marks G, Jeffries WL, 4th, Bingham T, Lauby J, et al. Mistaken assumptions and missed opportunities: correlates of undiagnosed HIV infection among black and Latino men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011; 58:64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mdodo R, Thomas PE, Walker A, Chavez P, Ethridge S, Oraka E, et al. Rapid HIV testing at gay pride events to reach previously untested MSM: U.S., 2009-2010. Public Health Rep 2014; 129:328–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellen JM, McCree DH, Muvva R, Chung SE, Miazad RM, Arrington-Sanders R, et al. Recruitment approaches to identifying newly diagnosed HIV infection among African American men who have sex with men. Int J STD AIDS 2013; 24:335–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levensky ER, Forcehimes A, O’Donohue WT, Beitz K. Motivational interviewing: an evidence-based approach to counseling helps patients follow treatment recommendations. Am J Nurs 2007; 107:50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract 2005; 55:305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mbuagbaw L, Ye C, Thabane L. Motivational interviewing for improving outcomes in youth living with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 9: CD009748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naar-King S, Outlaw A, Green-Jones M, Wright K, Parsons JT. Motivational interviewing by peer outreach workers: a pilot randomized clinical trial to retain adolescents and young adults in HIV care. AIDS Care 2009; 21:868–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foster C, McDonald S, Frize G, Ayers S, Fidler S. ‘Payment by Results’: financial incentives and motivational interviewing, adherence interventions in young adults with perinatally acquired HIV-1 infection: a pilot program. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2014; 28:28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craw JA, Gardner LI, Marks G, Rapp RC, Bosshart J, Duffus WA, et al. Brief strengths-based case management promotes entry into HIV medical care: results of the antiretroviral treatment access study-II. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 47:597–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Academy for Educational Development Center on AIDS and Community Health (COACH). ARTAS Linkage Case Management Implementation manual. Available at https://effectiveinterventions.cdc.gov/docs/default-source/artas-materials/artas-implemenation-forms—cd/artas-im-june-2015.pdf?sfvrsn=2 [Accessed 29 December 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Effective interventions, HIV Prevention that works accessed at https://effectiveinterventions.cdc.gov/en/highimpactprevention/PublicHealthStrategies.aspx, December 2016 [Accessed 29 December 2016]. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, Loughlin AM, del Rio C, Strathdee S, et al. Antiretroviral Treatment and Access Study Group. Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS 2005; 19:423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camacho-Gonzalez AF, Wallins AT, Murray LA, Zaneta G, Madeline S, Scott G, et al. Key Elements for Venue-based HIV-testing and Linkage to care for Adolescent and Young Adults in Metropolitan Atlanta. Abstract Presented at the 20th International AIDS Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camacho-Gonzalez AF, Wallins A, Toledo L, Murray A, Gaul Z, Sutton MY, et al. Risk factors for HIV transmission and barriers to HIV disclosure: metropolitan Atlanta youth perspectives. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2016; 30:18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller WR, Stephen R. Motivational interviewing helping people change. The Guilford Press, Third ed.USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biolytical Laboratories Accesed at http://www.biolytical.com/products/instiHIV [Accessed 29 December 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dominguez Rosales R, Albar Marin MJ, Tena Garcia B, Ruiz Perez MT, Garzon Real MJ, Rosado Poveda MA, et al. Effectiveness of the application of therapeutic touch on weight, complications, and length of hospital stay in preterm newborns attended in a neonatal unit. Enferm Clin 2009; 19:11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maissi E, Ridge K, Treasure J, Chalder T, Roche S, Bartlett J, et al. Nurse-led psychological interventions to improve diabetes control: assessing competencies. Patient Educ Couns 2011; 84:e37–e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Madson MB, Campbell TC. Measures of fidelity in motivational enhancement: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat 2006; 31:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mugavero MJ, Davila JA, Nevin CR, Giordano TP. From access to engagement: measuring retention in outpatient HIV clinical care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2010; 24:607–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States Updated to 2020; The White House 2015, accessed at https://www.aids.gov/federal-resources/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas-update.pdf [Accessed 18 December 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sprague C, Simon SE. Understanding HIV care delays in the US South and the role of the social-level in HIV care engagement/retention: a qualitative study. Int J Equity Health 2014; 13:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. HPTN 052 Study Team. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV-1 transmission. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:830–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. HPTN 052 Study Team. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah M, Risher K, Berry SA, Dowdy DW. The epidemiologic and economic impact of improving HIV testing, linkage, and retention in care in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:220–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]