Abstract

Objectives

Glucocorticoids (GC) are used to improve respiratory mechanics in preterm infants despite clinical evidence linking neonatal GC therapy to cerebellar pathology. In developing mouse cerebellum, the GC dexamethasone (DEX) causes rapid GC-induced neural progenitor cell apoptosis (GINA). Focusing on pharmacological neuroprotection strategies, we investigated whether dexmedetomidine (DMT) protects against GINA.

Methods

Neonatal mice were pretreated with DMT prior to DEX challenge. Additionally, we tested clonidine and yohimbine in vivo to determine mechanism of DMT neuroprotection. For in vitro studies, cerebellar neural progenitor cells were pretreated with DMT before DEX challenge.

Results

In vivo, DMT attenuated GINA at 1 μg/kg and above, p < 0.0001. Clonidine significantly attenuated GINA, p < 0.0001, while yohimbine reversed DMT neuroprotection, p < 0.0001, suggesting DMT neuroprotection is likely mediated via adrenergic signaling. In vitro, DMT neuroprotection was achieved at 10 μM and above, p < 0.001, indicating DMT rescue is cell autonomous.

Conclusions

DMT affords dose-dependent neuroprotection from GINA at clinically relevant doses, an effect that is cell autonomous and likely mediated by α2 adrenergic receptor agonism. DMT co-administration with GCs may be an effective strategy to protect the neonatal brain from GINA while retaining the beneficial effects of GCs on respiratory mechanics.

Keywords: dexmedetomidine, glucocorticoid, cerebellum, neuroprotection, neural progenitor cell, dexamethasone

Introduction

Premature infants often suffer from acute or prolonged respiratory dysfunction, which is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in this population [1, 2]. Respiratory dysfunction has multiple etiologies; however, it is commonly due to poor lung maturation (respiratory distress syndrome), premature respiratory drive (apnea of prematurity), or long-term mechanical ventilation (bronchoplumonary dysplasia). In the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), glucocorticoid (GC) therapy is indicated to accelerate lung development and wean preterm infants off ventilator support [3]. While GCs have been successful in treating respiratory sequelae and facilitating extubation, postnatal GC therapy is associated with adverse neurological outcomes. Yeh and colleagues found that premature infants treated with the synthetic GC dexamethasone (DEX) exhibited neuromotor deficits and lower IQ at school age when compared to a non-exposed cohort [4]. Furthermore, GC therapy has been linked to cerebellar hypoplasia in premature infants, which may underlie the neuromotor and cognitive abnormalities observed [5, 6, 7].

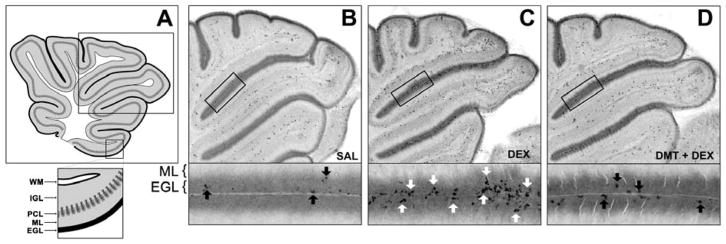

While the mechanism(s) of cerebellar hypoplasia associated with GC treatment has not been fully elucidated, our lab reported that a single exposure to clinically relevant doses of GCs — including DEX — causes rapid and selective apoptosis of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) in the external granule layer (EGL) of neonatal mice [8, 9]. Located on the outermost layer of the developing cerebellum, the EGL is a transient proliferative zone with well-defined inner and outer subdivisions. NPCs proliferate in the outer EGL, differentiate into granule cell neurons in the inner EGL, and migrate to the internal granule layer (IGL) to establish the architecture and functional connectivity of the mature cerebellum (Figure 1A). EGL NPC proliferation continues until postnatal day (PND) 14 in rodents and through the first year of life in humans [10].

Figure 1. Representative images of GINA and DMT neuroprotection against GINA.

In Panel A, the rectangle outlines the regions depicted in Panels B–D. The rectangle below Panel A magnifies the typical cytoarchitecture of the developing cerebellum including white (WM), internal granule layer (IGL), Purkinje cell layer (PCL), molecular (ML), and external granule layer (EGL). Panels B–D display AC3 immunolabeling in the EGL 6 hours after treatment. Panel B is an overview of a control animal, and the magnified region highlights AC3 positive NPCs undergoing physiologic apoptosis (black arrows). A single dose of 3 mg/kg of DEX caused a massive GINA response in the cerebellum (Panel C). AC3 positive NPCs are widely distributed throughout the extent of the EGL with clusters of NPCs dying en masse (magnified region, white arrows). Panel D, however, depicts the EGL of a pup pretreated with 1 μg/kg DMT before DEX challenge. Note the reduction of AC3 positive NPCs in the EGL (black arrows), consistent with DMT protecting against GINA at a clinically relevant dose. Panel A is reproduced from a previously published figure by K.K.N. under Creative Commons-BY license [8].

Previously, we reported that increased GC neurotransmission signals the end of cerebellar neurogenesis and, consequently, elimination of the EGL [8]. Taken together, our data suggest that exogenous GCs provide an artificial signal that prematurely halts cerebellar neurogenesis and eliminates the EGL by causing robust apoptosis in its resident NPCs. Depleting the pool of NPCs that generate millions of neurons results in irreversible cerebellar pathology [11]. We reported that neonatal exposure to GCs caused a dose-dependent reduction (up to 16%) of mature granule cell neurons in the IGL of adult mice, as well as permanent neurobehavioral deficits [9, 12]. This phenomenon led us to coin the term GC-induced NPC apoptosis (GINA), which may be the structural antecedent underlying cerebellar hypoplasia and neurodevelopmental abnormalities reported in premature infants that have received GC therapy.

Since GC therapy continues to be used in NICU settings, we have focused our research efforts on pharmacological neuroprotection, i.e., agents that attenuate GINA while retaining the therapeutic benefits of GCs. We recently reported that lithium provides dose-dependent neuroprotection against GINA caused by DEX [13]. However, safety concerns about lithium toxicity in neonates makes its clinical adoption challenging. In contrast, dexmedetomidine (DMT), an α2 adrenergic receptor agonist, is a sedative/analgesic with an excellent safety profile. Studies have demonstrated that DMT does not alter respiratory drive, and this lack of respiratory depression has led to DMT being used more frequently as a sedating agent in infants with neonatal respiratory distress secondary to respiratory distress syndrome, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and persistent pulmonary hypertension [14, 15, 16, 17]. Furthermore, preclinical studies report that DMT is neuroprotective against a variety of central nervous system insults [18, 19, 20, 21, 22].

Building on our established model of GINA and positive results with lithium, we tested the utility of DMT to attenuate GINA in vivo and in vitro. Pretreatment with DMT before DEX challenge caused a dose-dependent reduction of apoptosis in EGL NPCs of the developing cerebellum and partially rescued cultured primary EGL NPCs from GINA. Our data also suggest that DMT neuroprotection against GINA is mediated by α2 adrenergic receptor activation, a preliminary finding implicating an important role for this receptor subtype in EGL NPC survival. Clinically, DMT co-administration with GCs may be an effective strategy to protect the neonatal brain from GINA while retaining the benefits GCs on respiratory mechanics.

Materials and Methods

Animals

We used litters of ICR mice (Harlan, IN, USA) for all experiments. For in vivo experiments, PND7 ICR mouse pups were randomly assigned to experimental conditions. Vehicle or drug was delivered via the intraperitoneal route, and after initial injections, all pups were maintained separate from the mother in a V1200 Mediheat Veterinarian Recovery Chamber (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA) at 30 °C until sacrifice. In previous studies, we established that gender has no effect on GINA [9]; therefore, gender was not a factor in analyses. All animal care procedures were in accordance with procedures approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee and consistent with NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Drugs

Dexmedetomidine (R&D Systems 2749/10), yohimbine (Sigma Y3125-1G), DEX sodium phosphate USP (Sigma D9184), and DEX (Sigma D4902) were used for all experiments. DEX sodium phosphate is the phosphate ester of DEX and is highly soluble in water making it the preferred form used clinically. Once injected, this prodrug is rapidly converted to DEX. For in vivo experiments, DEX sodium phosphate was dissolved in saline with doses expressed as equimolar equivalents to DEX. DMT was administered 15 minutes prior to DEX, and booster doses of DMT were given at 2 and 4 hours after initial injection to ensure steady state levels of drug. Since the plasma enzymes that hydrolyze DEX sodium phosphate into DEX may be absent in vitro, DEX was used in cell culture experiments.

Histological Evaluation and Quantification of GINA

Immunohistochemistry

Activated caspase-3 (AC3) is a sensitive marker of apoptosis after neonatal exposure to ethanol, drugs of abuse, sedative/anesthetic agents, and GCs. Thus, brains were immunolabeled for AC3 per laboratory protocol [9, 13]. Briefly, six hours after initial injection, pups were deeply anesthetized and transcardially perfused via the left ventricle with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M Tris buffer. Brains were postfixed for several days before sagittal sectioning at 75 μm on a vibratome. Serial sections were quenched using methanol with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 minutes, blocked using 2% BSA, 0.2% milk, 0.1% Triton-X in PBS for an hour, and incubated overnight in 1:1000 anti-AC3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). The next morning, sections were incubated in goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), reacted with Vectastain ABC Elite Kit (Vector Laboratories), and visualized using the Vector VIP chromogen reagent (Vector Laboratories).

Quantification of GINA in EGL NPCs

Semiquantitative analysis of GINA was performed as described previously [8, 9, 13]. Briefly, a rater blind to treatment scored each cerebellum by examining several midsagittal sections per animal and evaluating the amount of AC3 positive NPCs in the EGL based on the following scale:

-

0

= no apoptotic profiles in all EGL regions

-

1

= apoptotic profiles are seen in a minority of EGL regions

-

2

= apoptotic profiles are seen in a majority of EGL regions, and

-

3

= apoptotic profiles are seen in all regions of the EGL

Cell Culture

Previously, we reported that B27 supplement contains corticosterone, an endogenous GC that is neurotoxic to EGL NPCs [13]. Since the inclusion of a physiologically relevant concentration of corticosterone in B27 supplement may confound analysis by interacting with DEX, we used corticosterone-free N2 supplement for all in vitro experiments. Cerebella were isolated from PND7 mouse pups and Papain digested with DNase at 37°C for 30 minutes. EGL NPCs were isolated from dissociated tissue using a 35%/65% Percoll fractionation using a 12 minute centrifugation at 2500 rpm as described previously [23]. Cells were then resuspended using 5 mL neurobasal with supplement, 1% sodium pyruvate, 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin supplemented with Sonic Hedgehog (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) at 0.625 μg/mL. Cells were supplemented with 2.25% N2 (Life Technologies, USA) as described above. Finally, 333 μL of resuspended cells were plated at 781,250 cells per well on poly-d-lysine coated glass coverslips in 24 well plates. All cells were incubated overnight and treated the following morning with 0 – 100 μM DMT one hour before challenge with 40 μM DEX. In vivo, DEX toxicity is observed within 6 hours, but in vitro, it is most prominent 24 hours after exposure [9, 24]. Therefore, in vivo, DMT was given 15 minutes prior to DEX injection and in vitro it was given one hour beforehand. 24 hours later, coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and labeled using AC3 and DAPI immunofluorescence as described previously [13]. Immunolabeled coverslips were then imaged using a Perkin Elmer UltraView Vox spinning disk confocal on a Zeiss Axiovert microscope at 40X. A rater blind to treatment calculated the number of AC3 positive cells for each well using NIH ImageJ. To avoid counts of non-specific staining or cell fragments, only AC3 positive cells containing DAPI co-labeling were counted. GINA is expressed as percentage of DAPI labeled cells that are AC3 positive.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed in Prism 5.0b (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) using one-way ANOVA (or two-way ANOVA when appropriate) with Bonferroni posthoc tests. All data are expressed as Mean ± SEM.

Results

DMT affords dose-dependent neuroprotection against GINA in vivo

Control animals had very few AC3 positive NPCs in the EGL (Figure 1B), which is consistent with the natural rate of cell death in developing cerebellum. However, DEX treated animals displayed robust GINA as indicated by increased EGL apoptosis (Figure 1C). Semiquantitative analysis revealed an overall effect of treatment, F(3, 11) = 30.77, p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.90 (Figure 2A). Specifically, posthoc evaluation revealed that DEX significantly increased GINA compared to controls (p < 0.0001), while pretreatment with 25 μg/kg DMT partially attenuated GINA caused by DEX, p < 0.001.

Figure 2. DMT is neuroprotective against GINA in vivo and in vitro.

Panel A illustrates that 3 mg/kg DEX (n = 3) significantly increased mean degeneration score compared to control animals (n = 5) and those treated with 25 μg/kg DMT alone (n = 3). In contrast, pups administered DMT + DEX (n = 4) had significantly lower degeneration scores versus the DEX cohort. The data in Panel B illustrate that DMT neuroprotection in vivo was dose-dependent at 1 μg/kg and above (n ≥ 6 for each dose), suggesting that therapeutic doses of DMT consistent with neonatal sedation protocols may attenuate GINA. DMT also protected against GINA in vitro (Panel C). Using primary EGL NPC cell culture, challenge with 40 μM DEX significantly increased the percentage of AC3 positive cells per well. However, pretreatment with 10, 50, and 100 μM of DMT significantly reduced AC3 positivity (n ≥ 29 wells for each dose), suggesting that DMT neuroprotection against GINA is cell autonomous.

**p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001

To determine whether DMT neuroprotection is dose-dependent, a separate cohort of animals was administered 0, 0.1, 1, 25, or 100 μg/kg of DMT prior to 3 mg/kg of DEX or vehicle. DMT partially attenuated GINA at nearly all doses tested, F(5, 46) = 26.67, p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.74. Pretreatment with 1, 25, or 100 μg/kg DMT significantly reduced apoptosis compared to DEX-only animals, p < 0.0001 for all comparisons (Figure 2B). Notably, DMT afforded neuroprotection against GINA at 1 μg/kg, a dose consistent with neonatal sedation protocols [15, 25]. Figure 1D is a representative image from a 1 μg/kg DMT + 3 mg/kg DEX animal and depicts the reduction of AC3 positive profiles in the EGL.

DMT is neuroprotective against DEX-induced apoptosis in vitro

To investigate whether DMT is neuroprotective directly on NPCs rather than acting through other cellular intermediaries in cerebellum (or body), we pretreated primary EGL NPC cultures with 0, 1, 10, 50, or 100 μM of DMT one hour before challenge with 40 μM of DEX and assessed apoptosis 24 hours later. Consistent with our in vivo data, pretreatment with DMT significantly reduced, but did not completely reverse, GINA, F(4, 142) = 12.85, p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.27. Posthoc analysis revealed that concentrations of 10, 50, and 100 μM of DMT attenuated DEX-induced apoptosis, p < 0.001, p < 0.001, and p < 0.0001, respectively (Figure 2C). The ability of DMT to suppress GINA in vitro suggests that DMT rescue may be partially cell autonomous.

DMT neuroprotection against GINA is mediated by α2 adrenergic receptor agonism

The putative mechanism of DMT neuroprotection is α2 adrenergic receptor agonism. If α2 receptor activation is essential for DMT neuroprotection, then other α2 agonists are expected to reduce DEX-induced apoptosis while α2 antagonists are expected to inhibit DMT neuroprotection.

To test this hypothesis, we pretreated pups with 1 mg/kg clonidine, an α2 agonist, before DEX challenge. There was a significant overall effect of clonidine treatment, F(2, 13) = 28.95, p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.82. Posthoc evaluation revealed that clonidine significantly attenuated GINA versus animals receiving DEX only, p < 0.001 (Figure 3A). A separate set of pups were pretreated with 10 mg/kg yohimbine, a high-affinity α2 antagonist, or vehicle and then randomly assigned to receive 1 μg/kg DMT (the lowest neuroprotective dose in vivo) or vehicle prior to DEX. As expected, yohimbine restored GINA after DMT + DEX administration, F(1, 19) = 29.22, p = 0.0001, R2 = 0.54 (Figure 3B). Specifically, pretreatment with yohimbine completely reversed DMT neuroprotection against DEX-induced apoptosis, p = 0.038. These data support the conclusion that DMT neuroprotection against GINA is mediated by α2 adrenergic receptor activation.

Figure 3. DMT neuroprotection acts through α2 adrenergic receptor agonism.

Panel A displays a statistically significant increase in GINA in pups treated with 3 mg/kg DEX (n = 5) versus control animals (n = 5). Pretreatment with 1 mg/kg of clonidine before DEX challenge (n = 6) led to a statistically significant reduction of GINA. In Panel B, saline (SAL) alone (n = 10) or 10 mg/kg yohimbine (YOH) alone (n = 2) had no effect on degeneration scores. However, pretreatment with YOH before DMT + DEX (n = 4) reversed DMT neuroprotection in animals treated with only DMT + DEX (n = 7). Taken together, our data suggest that DMT neuroprotection is mediated by α2 adrenergic receptor agonism.

*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.0001

Discussion

In a series of studies, we report that DMT attenuates GINA in vivo and in vitro. Our results provide valuable preliminary data regarding pharmacological neuroprotection against GINA in the developing cerebellum and add to a growing body of literature that DMT is neuroprotective against a range of central nervous system insults. DMT significantly attenuated GINA neurotoxicity in a dose-dependent manner (1 μg/kg and above), and partially rescued cultured EGL NPCs from DEX-induced apoptosis at concentrations of 10 μM and above. Importantly, neuroprotection was achieved at a dose in vivo (1 μg/kg) that is consistent with DMT sedation protocols in neonatal medicine (0.2–2 μg/kg/hr) [15, 25]. Furthermore, our data suggest that the anti-apoptotic properties of DMT are mediated via α2 adrenergic receptor activation. Administration of clonidine, another α2 agonist, protected against GINA, while yohimbine, a potent α2 antagonist, completely reversed DMT neuroprotection.

Taken together, our data implicate α2 adrenergic receptor activation as an important, but not exclusive, determinant of EGL NPC survival after GC challenge. Norepinephrine (NE) is the endogenous ligand of the three major adrenergic receptor subtypes (α1, α2, and β), which act in concert to modulate cerebellar function [26]. In rodent cerebellum, α2 receptors are transiently expressed at very high levels from P1 to P10 before declining to adult levels by PND14 [27]. In contrast, endogenous GC activity in cerebellum is low during the first two weeks of postnatal life, allowing EGL NPCs to proliferate, differentiate, and migrate to their final destination in the IGL [8]. As the window of neurogenesis closes around PND14, GC neurotransmission increases substantially, and activated GC receptors begin transcribing target genes. This opposing pattern of high α2 receptor expression but low GC activity in the first two weeks of life makes it tempting to suggest crosstalk between GC and NE systems during cerebellar ontogenesis. However, there is limited evidence that such an interaction occurs in developing cerebellum.

Slotkin and colleagues [28] found that chronic administration of DEX to pregnant rats caused premature maturation of NE circuitry in the cerebellum of their offspring. At PND30, pups exposed to DEX in utero exhibited adult-like levels of NE and turnover. Interestingly, by adulthood, these animals had significantly lower NE levels and turnover compared to controls, suggesting that DEX can permanently dysregulate adrenergic signaling. However, in our studies, DEX-induced GINA and DMT neuroprotection occurred within 6 hours, which is not enough time for whole scale remodeling of NE circuitry.

Instead, our data are consistent with EGL NPCs expressing functional, NE competent α2 receptors that respond extremely quickly to apoptotic stimuli. In vitro, DMT partially attenuated GINA within 24 hours of DEX challenge, suggesting that α2 activation provides rapid, cell autonomous neuroprotection. Indeed, other researchers reported similar findings in which DMT promotes cell survival within hours of a diverse range of insults by increasing phosphorylation of ERK and expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-1, as well as preserving PI3K/Akt signaling [18, 21, 29]. Explaining the observed partial rescue of EGL NPCs by DMT in vivo is more complex given the widespread expression of α2 receptors on interneurons in cerebellum, as well as on locus coeruleus projection neurons that innervate the cerebellum [26]. Although elucidating cell extrinsic neuroprotective mechanisms was beyond the scope of the current studies, a reasonable hypothesis is that DMT may indirectly mitigate GINA by upregulating anti-apoptotic factors and increasing the release of neurotrophins promoting cell survival [26].

Conclusion

Synthetic GCs such as DEX are indicated to improve respiratory mechanics in premature infants experiencing respiratory dysfunction [3] despite clinical evidence linking GC therapy to cerebellar hypoplasia [5, 6, 7] and long-term neurodevelopmental abnormalities [4]. Consistent with previous studies [8, 9, 13], we report that a single dose of DEX was sufficient to cause GINA – rapid and selective apoptosis of EGL NPCs – in neonatal mice. Pretreatment with DMT, a α2 adrenergic receptor agonist, partially rescued EGL NPCs from GINA in vivo and in vitro. Given that DMT does not alter respiratory drive, it is being used more frequently as a sedative/analgesic in premature infants with respiratory distress. Our data suggest that co-administration of a moderate dose of DMT may protect premature infants from cerebellar pathology associated with GC therapy while retaining the benefits of GCs on respiratory mechanics. Finally, DMT pretreatment was able to substantially suppress, but not completely reverse, GINA. Thus, DMT may be of immediate neuroprotective utility, but a continued research effort to screen for additional agents that may further suppress GINA is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Funding Details

This work was supported by: K.K.N. NIH grants MH083046, HD052664, HD052664S, HD083001, and the Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center at Washington University in St. Louis (NIH/NICHD U54-HD087011). J.D.D. NIH grants MH109133, HG008687, MH100027, and DA038458. S.S. Washington University HHMI-WU Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) Program.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Shawn David O’Connor, Edward Mallinckrodt Department of Pediatrics, Division of Newborn Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine and St. Louis Children’s Hospital, St., Louis, St. Louis, Missouri, USA, One Children’s Place, CB8116 NWT8, Phone: 1 314 454-2683.

Omar Hoseá Cabrera, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA, 660 South Euclid, Box #8134, Phone: 1 314 362-2483.

Joseph D. Dougherty, Department of Genetics and Department of Psychiatry, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA, 660 South Euclid, Box #8064, Phone: 1 314 286-0752.

Sukrit Singh, Division of Biology and Biomedical Sciences and Department of Genetics, Washington, University in St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri, USA, 660 South Euclid, Box #8231, Phone: 1 314 362-7434.

Brant Stephen Swiney, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA, 660 South Euclid, Box #8134, Phone: 1 314 362-2482.

Patricia Salinas-Contreras, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA, 660 South Euclid, Box #8134, Phone: 1 314 362-2483.

Nuri Bradford Farber, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA, 660 South Euclid, Box #8134, Phone: 1 314 362-2462.

Kevin Kiyoshi Noguchi, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine 660 South Euclid, Box #8134 St. Louis, MO 63110 Phone: 314-362-7007.

References

- 1.Barton L, Hodgman JE, Pavlova Z. Causes of death in the extremely low birth weight infant. Pediatrics. 1999;103:446–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.2.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel RM, Kandefer S, Walsh MC, Bell EF, Carlo WA, Laptook AR, Sanchez PJ, Shankaran S, Van Meurs KP, Ball MB, Hale EC, Newman NS, Das A, Higgins RD, Stoll BJ Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child H, Human Development Neonatal Research N. Causes and timing of death in extremely premature infants from 2000 through 2011. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:331–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halliday HL, Ehrenkranz RA, Doyle LW. Moderately early (7–14 days) postnatal corticosteroids for preventing chronic lung disease in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000:CD001144. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeh TF. Outcomes at school age after postnatal dexamethasone therapy for lung disease of prematurity. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350:1304–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parikh NA, Lasky RE, Kennedy KA, Moya FR, Hochhauser L, Romo S, Tyson JE. Postnatal dexamethasone therapy and cerebral tissue volumes in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2007;119:265–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tam EW, Chau V, Ferriero DM, Barkovich AJ, Poskitt KJ, Studholme C, Fok ED, Grunau RE, Glidden DV, Miller SP. Preterm cerebellar growth impairment after postnatal exposure to glucocorticoids. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:105ra. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheong JL, Burnett AC, Lee KJ, Roberts G, Thompson DK, Wood SJ, Connelly A, Anderson PJ, Doyle LW Victorian Infant Collaborative Study G. Association between postnatal dexamethasone for treatment of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and brain volumes at adolescence in infants born very preterm. J Pediatr. 2014;164:737–43. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noguchi KK, Lau K, Smith DJ, Swiney BS, Farber NB. Glucocorticoid receptor stimulation and the regulation of neonatal cerebellar neural progenitor cell apoptosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;43:356–63. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noguchi KK, Walls KC, Wozniak DF, Olney JW, Roth KA, Farber NB. Acute neonatal glucocorticoid exposure produces selective and rapid cerebellar neural progenitor cell apoptotic death. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1582–92. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carletti B, Rossi F. Neurogenesis in the cerebellum. Neuroscientist. 2008;14:91–100. doi: 10.1177/1073858407304629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohn MC, Lauder JM. The effects of neonatal hydrocortisone on rat cerebellar development. Developmental Neuroscience. 1978;1:250–66. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maloney SE, Noguchi KK, Wozniak DF, Fowler SC, Farber NB. Long-term Effects of Multiple Glucocorticoid Exposures in Neonatal Mice. Behav Sci (Basel) 2011;1:4–30. doi: 10.3390/behavsci1010004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cabrera O, Dougherty J, Singh S, Swiney BS, Farber NB, Noguchi KK. Lithium protects against glucocorticoid induced neural progenitor cell apoptosis in the developing cerebellum. Brain Res. 2014;1545:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siddappa R, Riggins J, Kariyanna S, Calkins P, Rotta AT. High-dose dexmedetomidine sedation for pediatric MRI. Paediatr Anaesth. 2011;21:153–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chrysostomou C, Schulman SR, Herrera Castellanos M, Cofer BE, Mitra S, da Rocha MG, Wisemandle WA, Gramlich L. A phase II/III, multicenter, safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetic study of dexmedetomidine in preterm and term neonates. J Pediatr. 2014;164:276–82. e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Mara K, Gal P, Wimmer J, Ransom JL, Carlos RQ, Dimaguila MA, Davanzo CC, Smith M. Dexmedetomidine versus standard therapy with fentanyl for sedation in mechanically ventilated premature neonates. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2012;17:252–62. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-17.3.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner DS, Brummett CM. Dexmedetomidine: as safe as safe can be. Seminars in Anesthesia, Perioperative Medicine and Pain. 2006;25:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanders RD, Sun P, Patel S, Li M, Maze M, Ma D. Dexmedetomidine provides cortical neuroprotection: impact on anaesthetic-induced neuroapoptosis in the rat developing brain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54:710–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanders RD, Xu J, Shu Y, Januszewski A, Halder S, Fidalgo A, Sun P, Hossain M, Ma D, Maze M. Dexmedetomidine attenuates isoflurane-induced neurocognitive impairment in neonatal rats. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1077–85. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819daedd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X. Dexmedetomidine attuenuates isoflurane-induced cognitive impairment through antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptosis in aging rat. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 2015;8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu YM, Wang CC, Chen L, Qian LB, Ma LL, Yu J, Zhu MH, Wen CY, Yu LN, Yan M. Both PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 pathways participate in the protection by dexmedetomidine against transient focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Brain Res. 2013;1494:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schoeler M, Loetscher PD, Rossaint R, Fahlenkamp AV, Eberhardt G, Rex S, Weis J, Coburn M. Dexmedetomidine is neuroprotective in an in vitro model for traumatic brain injury. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dougherty JD, Garcia AD, Nakano I, Livingstone M, Norris B, Polakiewicz R, Wexler EM, Sofroniew MV, Kornblum HI, Geschwind DH. PBK/TOPK, a proliferating neural progenitor-specific mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10773–85. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3207-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heine VM, Rowitch DH. Hedgehog signaling has a protective effect in glucocorticoid-induced mouse neonatal brain injury through an 11betaHSD2-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:267–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI36376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McPherson C, Grunau RE. Neonatal pain control and neurologic effects of anesthetics and sedatives in preterm infants. Clin Perinatol. 2014;41:209–27. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandler DJ, Nicholson SE, Zitnik G, Waterhouse BD. Norepinephrine and Synaptic Transmission in the Cerebellum. 2013:895–914. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Happe HK, Coulter CL, Gerety ME, Sanders JD, O’Rourke M, Bylund DB, Murrin LC. Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor development in rat CNS: an autoradiographic study. Neuroscience. 2004;123:167–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slotkin TA, Lappi SE, McCook EC, Tayyeb MI, Eylers JP, Seidler FJ. Glucocorticoids and the development of neuronal function: effects of prenatal dexamethasone exposure on central noradrenergic activity. Biol Neonate. 1992;61:326–36. doi: 10.1159/000243761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Zeng M, Chen W, Liu C, Wang F, Han X, Zuo Z, Peng S. Dexmedetomidine reduces isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis partly by preserving PI3K/Akt pathway in the hippocampus of neonatal rats. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]