Abstract

Purpose

To inform the evolving implementation of CancerLinQ and other rapid-learning systems for oncology care, we sought to evaluate perspectives of patients with cancer regarding ethical issues.

Methods

Using the GfK Group online research panel, representative of the US population, we surveyed 875 patients with cancer; 621 (71%) responded. We evaluated perceptions of appropriateness (scored from 1 to 10; 10, very appropriate) using scenarios and compared responses by age, race, and education. We constructed a scaled measure of comfort with secondary use of deidentified medical information and evaluated its correlates in a multivariable model.

Results

Of the sample, 9% were black and 9% Hispanic; 38% had completed high school or less, and 59% were age ≥ 65 years. Perceptions of appropriateness were highest when consent was obtained and university researchers used data to publish a research study (weighted mean appropriateness, 8.47) and lowest when consent was not obtained and a pharmaceutical company used data for marketing (weighted mean appropriateness, 2.7). Most respondents (72%) thought secondary use of data for research was very important, although those with lower education were less likely to endorse this (62% v 78%; P < .001). Overall, 35% believed it was necessary to obtain consent each time such research was to be performed; this proportion was higher among blacks/Hispanics than others (48% v 33%; P = .02). Comfort with the use of deidentified information from medical records varied by scenario and overall was associated with distrust in the health care system.

Conclusion

Perceptions of patients with cancer regarding secondary data use depend on the user and the specific use of the data, while also frequently differing by patient sociodemographic factors. Such information is critical to inform ongoing efforts to implement oncology learning systems.

INTRODUCTION

Advances and public investments in health information technology have promoted the increased adoption of electronic health records,1 inspiring development of systems to leverage these data to transform cancer care.2 The National Academy of Medicine has emphasized the concept of rapid-learning systems that harness patient data collected during routine care to drive the process of discovery, making research a natural outgrowth of clinical practice and quality improvement part of a continuous virtuous cycle.3

Although promising, this vision blurs the traditional distinction between clinical practice, quality improvement, and research, necessitating careful consideration of ethical limits on data use.4-6 To avoid harm and promote respect for persons, those implementing such systems must develop an appropriate process for notification and/or consent and create trustworthy systems governing data use. Although the current legal and regulatory structures for use of patient information allow for uses of deidentified patient data for research, what is legally permissible2 may not always be perceived as ethically appropriate. We know little about patients’ perspectives on these issues. Existing evidence suggests that trust is critical7-9; privacy concerns persist despite the implementation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).10 Many individuals prefer consent or the ability to restrict access to their own data11-14; use, user, and sensitivity affect patients’ attitudes,15-17 and attitudes may differ by demographic characteristics18 or nationality.19

We know even less about how patients with cancer view the use of their information, but there is reason to believe their perspectives may differ from those of the general public. In one early survey, patients with breast cancer were less likely than others to think that a computerized database of medical records was a good idea in general but were also more likely than others to endorse such a database for research purposes if it was anonymized.20 A more recent post hoc analysis of a general population survey suggested that patients with cancer may be more willing than others to allow access to sensitive data.21

Given that the potential of a rapid-learning system is particularly great in complex fields such as oncology,22 the American Society of Clinical Oncology is actively developing a real-world rapid-learning system for oncology care known as CancerLinQ. CancerLinQ draws data from full electronic medical records in real time, with a primary focus on quality improvement but also with the expectation of allowing secondary data use for research, moving considerably beyond what has been accomplished by cancer registries to date. Understanding perspectives of patients with cancer is critically important for the evolving implementation of CancerLinQ and other rapid-learning systems for oncology care. Therefore, we elicited perspectives of patients with cancer regarding the ethical implementation of rapid-learning systems in oncology care in a national survey study.

METHODS

Sampling and Data Collection

After approval by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board, we used the GfK Group online research panel to recruit noninstitutionalized adult patients with cancer of any site other than skin (which we excluded because of the high prevalence of nonmelanomatous skin cancers, where the patient experience is typically quite different from that in other cancers) to respond to our survey. To sample the population, GfK sampled households from its KnowledgePanel, a probability-based Web panel designed to be representative of the US population.

GfK randomly recruits panel members through probability-based sampling using address-based methods with information from the US Postal Service Delivery Sequence File. Recruitment includes geographic stratification, whereby Census Block Groups with high-density minority communities are oversampled and ancillary information about addresses is used to target households on the basis of age. As described in the analysis section, specific adjustments are applied to compensate for any oversampling that is carried out to improve the demographic composition of the panel.

Households are provided with access to the Internet and hardware if needed. After initially accepting the invitation to join the panel, participants are asked to complete a short initial profile survey that includes demographic and other basic information to allow for appropriate sampling and weighting for future surveys. Panel members are notified by e-mail or through their online member page of survey opportunities.23-25 GfK provides modest incentives (such as raffles for cash and other prizes) to encourage participation and create member loyalty. The typical survey commitment for panel members is one 10- to 15-minute survey per week.

Our survey involved two stages: initial screening to confirm cancer diagnosis and eligibility followed by the main survey for eligible respondents. In November 2015, after a pretest to ensure instrument validity and integrity, 875 patients believed eligible on the basis of GfK records were sampled, of whom 643 (73.5%) completed the screening questions; 621 (96.6%) of these respondents qualified for the main questionnaire (by confirming they were adults with a history of nonskin cancer). In keeping with standard practices of GfK, e-mail reminders to nonresponders were sent on days 3 and 6 of the field period.

Measures

Full questionnaire content is available in the Data Supplement. Patients self-reported sex, age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, employment, and insurance status. They also reported cancer site, year of diagnosis, stage at diagnosis, treatments received, and whether they had ever been told the cancer was incurable, had spread to other parts of their body, or was metastatic. They reported their general overall heath using the Short Form-126 and their satisfaction with health care using an item from a previous study7 derived from the VA TRIAD (Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes) study.27 They reported whether any of their physicians used electronic medical records and whether they were concerned about the privacy of electronic medical records. They reported their general distrust of the health system using the Revised Health Care System Distrust nine-item scale,28 and they reported whether they were generally concerned about personal privacy in the United States today (using a four-point scale grouped for analysis; high, very concerned; moderate, somewhat concerned; or low, a little or not at all concerned). They reported whether they had heard of HIPAA and whether they were aware that “under some circumstances, your medical record could be used in some research studies without your permission.”

We evaluated perceptions of appropriateness of several detailed scenarios relating to secondary use of electronic health information, using items adapted from a prior study.16 Respondents were first told: “Many doctors and hospitals are starting to use electronic medical records instead of paper charts when they provide care. Electronic medical records can also be used for other health care and public health reasons. You will be shown some possible uses of electronic health information. In each case, you will be shown what health information will be used, who will use it, and what they will use it for. Please indicate how appropriate is the use of health information in each situation.” They were then shown (in random order) four scenarios that varied the terms relating to consent (explicit or not) and use/user (university researchers who publish results in a medical journal versus drug company that uses information to sell more of its drug). Responses ranged from 1 (not at all appropriate) to 10 (very appropriate).

We evaluated patients’ perceptions regarding the competing considerations of the need for research using secondary data and the need to gain consent for data use by asking them: “When medical researchers study the causes of diseases, the effectiveness of medications, or ways to improve medical care, it is often necessary for them to use medical records from hospitals, doctors' offices, or other health care institutions. With the development of electronic health record systems, it is also possible to collect this information and remove details that identify patients (such as name and date of birth), before providing the information to researchers. When this kind of research is done, no personally identifiable health information is given to the researcher. In your opinion, how important is it…

To be able to conduct this kind of medical research?

For doctors to get a patient's permission to use their medical record each time their medical record is used for this kind of research, even if it means that a great deal of research will not be done?

For there to be a way to share a patient's medical records with researchers to do this kind of research without having to ask permission each time?

For doctors to ask a patient at least once whether researchers can use their medical record for all future research of this kind?”

Responses were rated from critically important to not at all important using a 5-point scale.

Finally, given prior work suggesting that comfort was the ultimate patient-centered outcome of interest in this setting,8 we assessed comfort using a four-point scale from very uncomfortable to very comfortable with different situations “where someone might wish to use your medical records, after removal of identifying data like your name and date of birth.” The specific situations are detailed in Appendix Figure A1 (online only) and Data Supplement as well as in Appendix Tables A1 and A2 (online only).

Statistical Analysis

Complex survey weights supplied by GfK were applied for all analyses (including models) to ensure that the respondent sample was representative. The dimensions included in the weighting included sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, census region, home ownership status, metropolitan area, and Internet access (Appendix, online only).

Descriptive statistics were generated for the sample overall and by the three key subgroups suggested in prior literature as potentially meaningful: age (≥ 65 v < 65 years), race/ethnicity (black or Hispanic v not), and educational status (at least some college v high school or less).

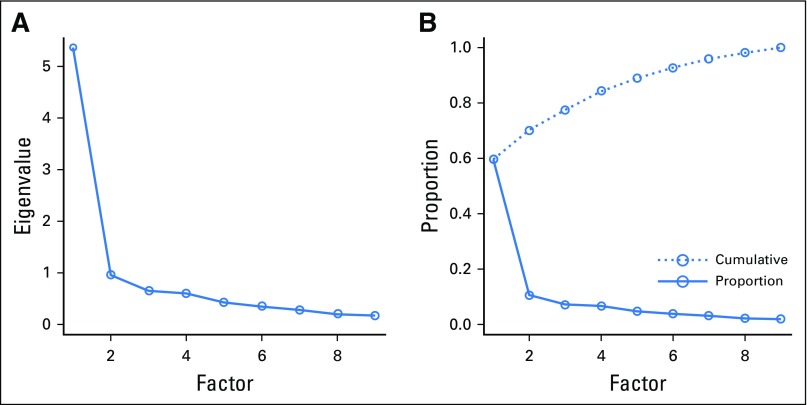

A scaled measure of comfort was then developed using the sum score of the nine items (each scored from 1 to 4). Item internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) and factor analysis were used to confirm a one-factor solution.

The scaled measure of comfort was the dependent variable in a multivariable linear regression model, after theoretically prespecifying the following as independent variables: age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, financial status, years since diagnosis, incurable/metastatic disease, and current health status. A second model added mechanistic factors of health care system distrust, general privacy concerns, and awareness that secondary use is sometimes already permitted.

RESULTS

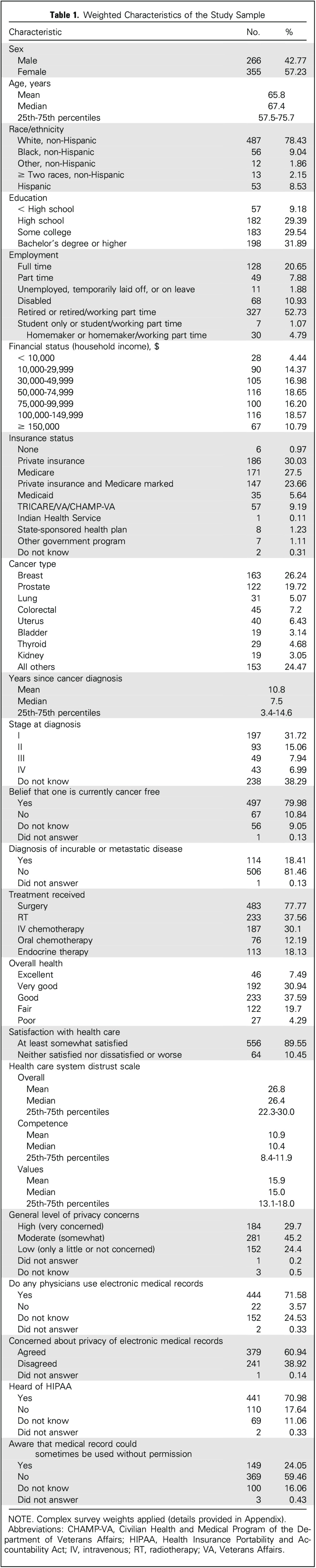

The weighted analytic sample was 57% female and racially diverse, with 9% black and another 9% Hispanic (Table 1). Overall, 38% had completed high school or less education, and 59% were age ≥ 65 years. Most (80%) believed they were currently cancer free, and the most common cancer types were breast (26%) and prostate (20%). Health status was excellent or very good for 38%. A vast majority (90%) were at least somewhat satisfied with health care. A majority (72%) reported that their physicians used electronic medical records; 30% expressed high concern about privacy in general, and 61% were concerned about privacy of electronic medical records. Mean distrust in the health care system was 26.8 on a validated scale ranging from 0 to 45. Most were aware of HIPAA (71%), but only 24% were aware that secondary use of their health information was already permissible in certain circumstances.

Table 1.

Weighted Characteristics of the Study Sample

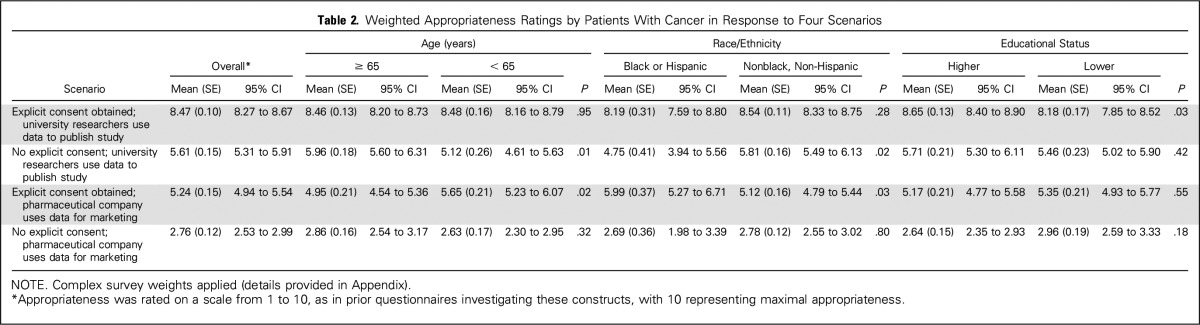

Overall perceptions of appropriateness (Table 2) were highest in the scenario where consent was obtained and university researchers were using the data to publish a research study (weighted mean appropriateness, 8.47); perceptions varied by education in this scenario, with those having higher education rating appropriateness higher (8.7 v 8.2; P = .03). For that same scenario, appropriateness scores fell to 5.6 when consent was not explicitly obtained, and racial minorities rated appropriateness lower than whites, as did younger compared with older patients. Scores were lowest in the scenario where consent was not obtained and a pharmaceutical company was using the data for marketing (2.7), with no variations observed by race, age, or educational status.

Table 2.

Weighted Appropriateness Ratings by Patients With Cancer in Response to Four Scenarios

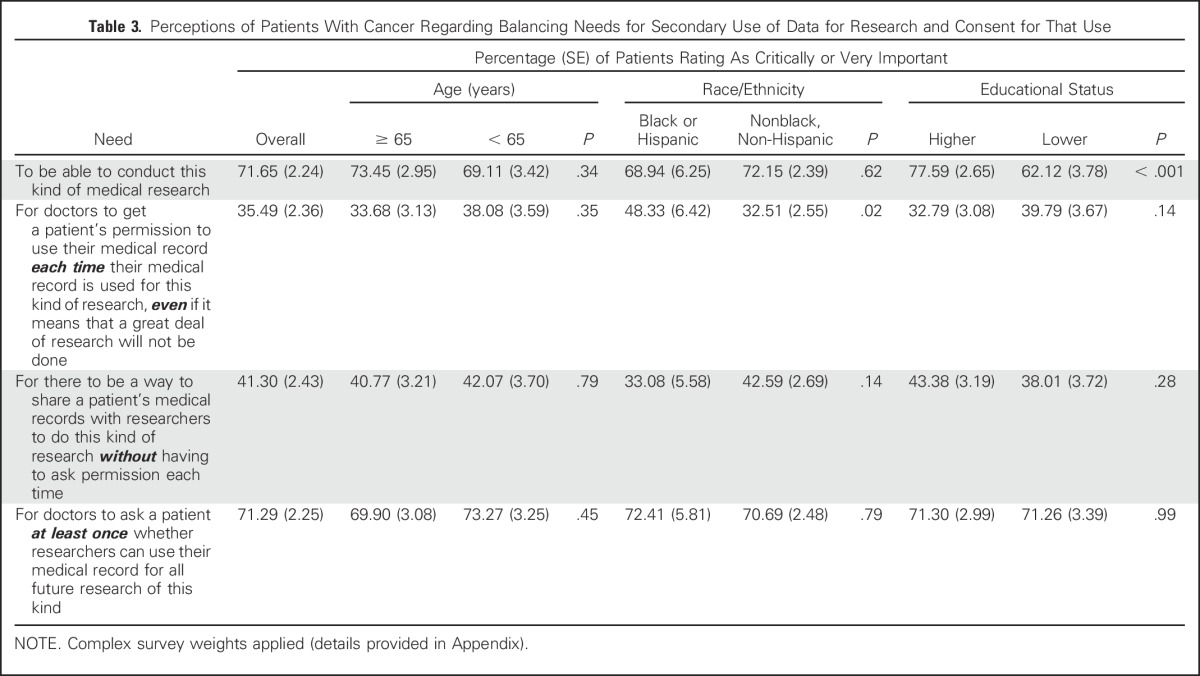

Table 3 demonstrates perceptions of patients with cancer regarding the balance between needs for secondary use of data for research and consent for that use. A majority (72%) thought it critically or very important to be able to conduct this kind of research, although those with lower education were less likely to endorse this than those who had attended at least some college (62% v 78%; P < .001). Only 35% believed it necessary to obtain consent each time such research was to be performed; this proportion was higher among blacks/Hispanics than others (48% v 33%; P = .02). Most believed that consent should be obtained at least once (71%), and this did not vary by age, race, or educational status.

Table 3.

Perceptions of Patients With Cancer Regarding Balancing Needs for Secondary Use of Data for Research and Consent for That Use

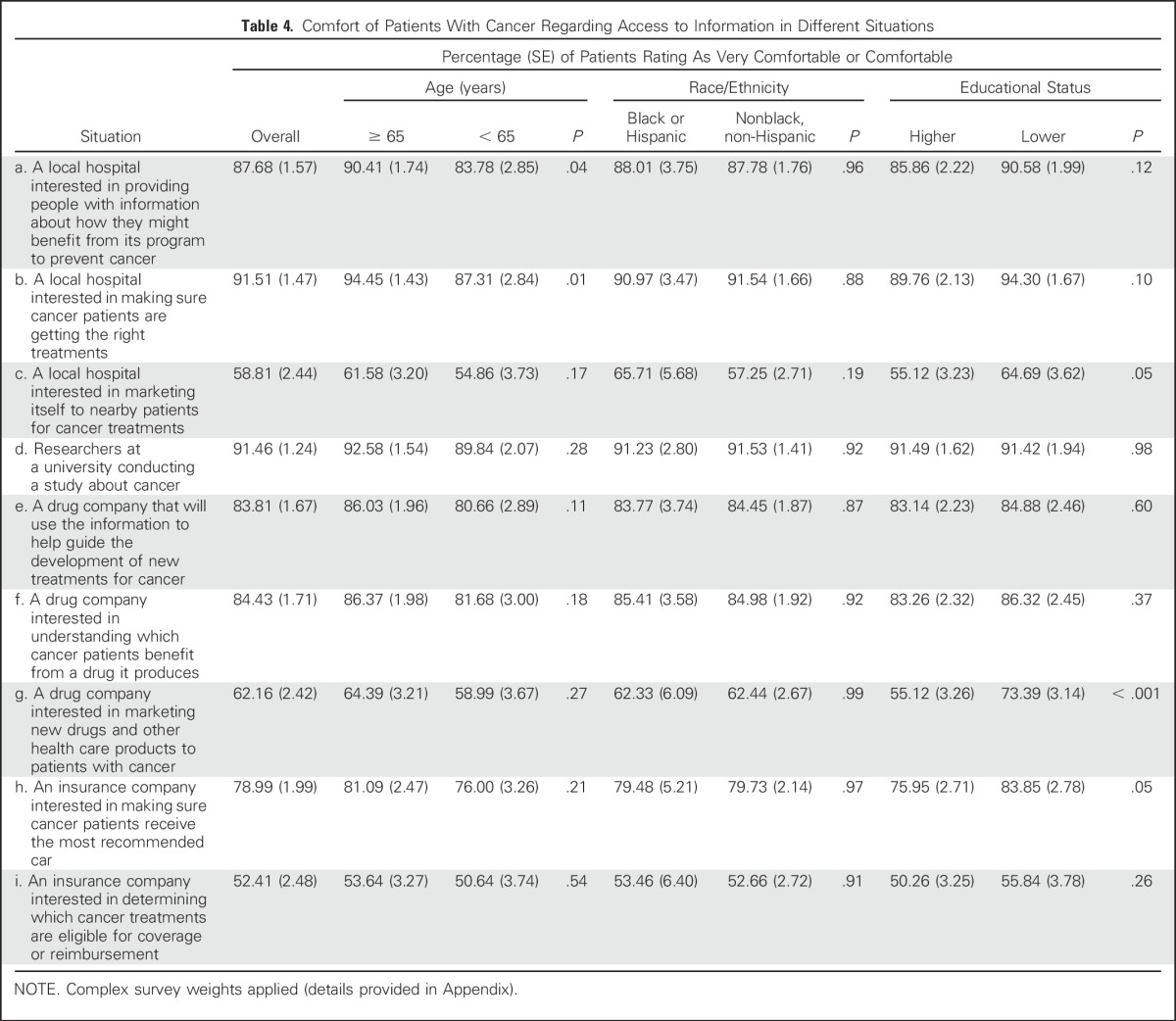

Comfort with the use of deidentified information from medical records varied depending on the specific situation, as summarized in Table 4, and also differed in some cases by age, race, and/or educational status. A large majority were comfortable (≥ 88%) when hospitals were the users, except when the data were being used for marketing. A vast majority were also comfortable with university research (91%). When drug companies were the users, a somewhat lower but still substantial proportion were comfortable (84%), except when the data were being used for marketing (62%). Fewer were comfortable when insurance companies were users, particularly if data were being used to determine coverage or reimbursement (52%).

Table 4.

Comfort of Patients With Cancer Regarding Access to Information in Different Situations

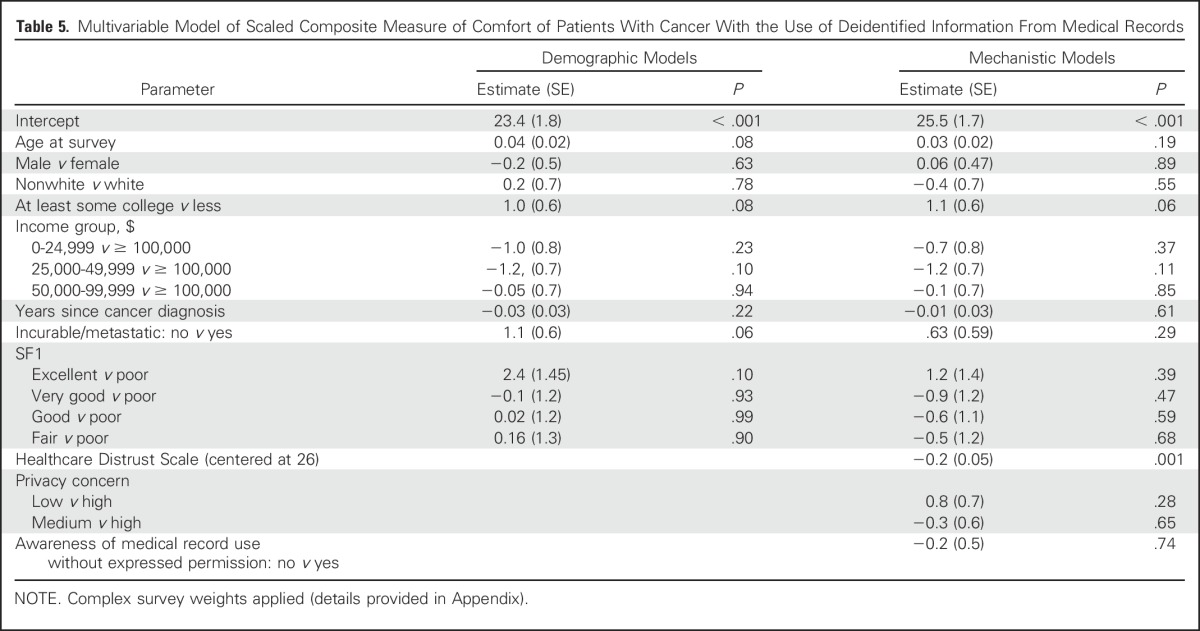

The scaled single measure of comfort was highly internally consistent (α = 0.91). Removing any single item reduced internal consistency, so a sum score scale was created (Appendix Fig A1). On multivariable analysis (Table 5), this scaled comfort outcome was significantly related to the Healthcare Distrust Scale (0.2 decrease in comfort for each point increase in distrust; P ≤ .001).

Table 5.

Multivariable Model of Scaled Composite Measure of Comfort of Patients With Cancer With the Use of Deidentified Information From Medical Records

DISCUSSION

This large national survey reveals that perceptions of patients with cancer of secondary data use are highly dependent on the ultimate user and the specific use of the data and frequently differ by age, race, and/or educational status of the respondent. Most patients with cancer appreciate the importance of secondary uses of data for research, but most also believe that consent should be obtained at least once. Comfort with the secondary use of aggregated and deidentified information from medical records is high for research use but lower for use in marketing. Those seeking to implement rapid-learning systems in oncology care should consider these findings when determining how best to regulate data use and communicate with patients about the wide-scale deployment of these systems, their implications for privacy and autonomy, and their potential to yield meaningful benefits for patients.

Our findings in this population of patients with cancer are consistent with those of other studies29 that have noted that racial and ethnic minorities may be particularly concerned about consent to any participation in research. Given the egregious historical trespasses inflicted upon such groups,30,31 along with recent attention to situations where inadequate respect was demonstrated for those whose routinely collected tissues proved essential to major medical advances,32 it is hardly surprising to observe that nearly half of the black or Hispanic patients in our sample desired consent to be obtained every time data were to be used for research. For rapid-learning systems to succeed, it is imperative to develop culturally sensitive forms of communication that clarify the protections in place and distinguish the currently proposed activities, which may actually finally yield data necessary to individualize care in ways that benefit racial and ethnic minorities, from the historical forms of covert research that failed to respect these groups, perpetuated inequities, and placed a disproportionate share of the burden of clinical research on the most vulnerable.

Similarly, the observation that less educated patients may be less likely to perceive the importance of secondary data use for research is also important. It suggests that explicitly articulating how such systems are designed to minimize risks and maximize benefits to society may help to illuminate the inherent promise of the virtuous cycle of rapid-learning systems to those who might not necessarily find it intuitive or obvious in the way that those privileged to have been exposed to greater education might.

Finally, distrust was a key correlate of comfort of patients with cancer, consistent with prior research in other populations.7,29 Therefore, efforts to build trust seem essential to ensure the success of the promising concept of rapid-learning systems. After all, the observation that a majority of patients believe that consent should be obtained at least once even in the setting of legally permissible use of deidentified data for research is striking; this poses an important challenge to those implementing rapid-learning systems. Outreach to explain the nature and intent of rapid-learning systems may be particularly important, and attention to various reasons patients might distrust the system as a whole should be a key consideration when designing interventions along these lines.

Although this study has strengths, including a high response rate from a national sample of diverse patients with cancer, it also has limitations. First, patients in this study were presented with hypothetical scenarios; future research involving patients in real-world rapid-learning systems will be important to evaluate perceptions of actual experiences. Second, those who participate in an online research panel might have more favorable attitudes toward research and fewer concerns about privacy than others, although the subgroup differences and differences in comfort across different scenarios should not be affected by this. Third, a vast majority of patients included were currently cancer free; the attitudes of those who have active disease merit further directed study. Fourth, we did not collect information on the setting of cancer care; future research should investigate whether attitudes differ among those seen in academic centers and community settings. Finally, by using a questionnaire administered once in time, this study could not evaluate whether attitudes and comfort might evolve if patients are provided with greater information and/or the opportunity to deliberate with their peers. Further research using deliberative democracy approaches33,34 to generate informed and considered opinions is particularly important to evaluate this critical unanswered question.

In summary, our study provides the first large-scale national data to our knowledge regarding perceptions of patients with cancer regarding the ethical implications of secondary uses of data for research in the context of the rapid-learning systems that are being developed for oncology care. Such information is critical to inform ongoing efforts to ensure that system implementation succeeds in engaging patients and earning their trust and support. Particular attention is warranted in the areas identified where patient expectations for ethical acceptability diverge from what is legally required.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the members of the 2014, 2015, and 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology Ethics Committees for their insights and contributions to study design and instrument pretesting.

Appendix

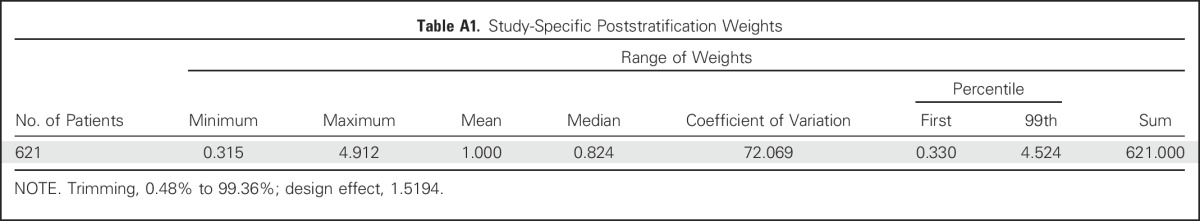

Sample Weighting

Significant resources and infrastructure are devoted to the recruitment process for the KnowledgePanel (KP) so that the resulting panel can properly represent the adult population of the United States. Not only is this representation achieved with respect to a broad set of geodemographic distributions, but hard-to-reach adults—such as those without landline telephones or Spanish language–dominant individuals—are recruited in proper proportions as well. Consequently, the raw distribution of KP mirrors that of US adults fairly closely, barring occasional disparities that may emerge for certain subgroups as a result of differential attrition rates among recruited panel members.

For selection of general population samples from KP, however, a patented methodology has been developed that ensures the resulting samples behave as an equal probability selection method sample from the panel. Briefly, this methodology starts by weighting the entire KP to the benchmarks secured from the latest March supplement of the Current Population Survey along several dimensions. This way, the weighted distribution of KP perfectly matches that of US adults, even with respect to the few dimensions where minor misalignments may result from differential attrition rates.

Typically, the geodemographic dimensions used for weighting the entire KP include: sex (male or female), age (18 to 29, 30 to 44, 45 to 59, or ≥ 60 years), race/ethnicity (white/non-Hispanic, black/non-Hispanic, other/non-Hispanic, ≥ two races/non-Hispanic, or Hispanic), education (< high school, high school, some college, or ≥ Bachelor’s degree), census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West), household income (< $10,000, $10,000 to < $25,000, $25,000 to < $50,000, $50,000 to < $75,000, or ≥ $75,000), metropolitan area (yes or no), and Internet access (yes or no).

Using the above weights as the measure of size for each panel member, in the next step, a probability proportional to size procedure is used to select study-specific samples. It is the application of this probability proportional to size methodology with the measure-of-size values listed in the previous paragraph that produces fully self-weighing samples from KP, for which each sample member can carry a design weight of unity. In instances like our survey, where the study design focuses on a subgroup of the overall KP (patients with cancer other than skin cancer), this approach is intended to produce a final weighted sample that reflects the characteristics of the overall population of patients with cancer other than skin cancer.

Table A1.

Study-Specific Poststratification Weights

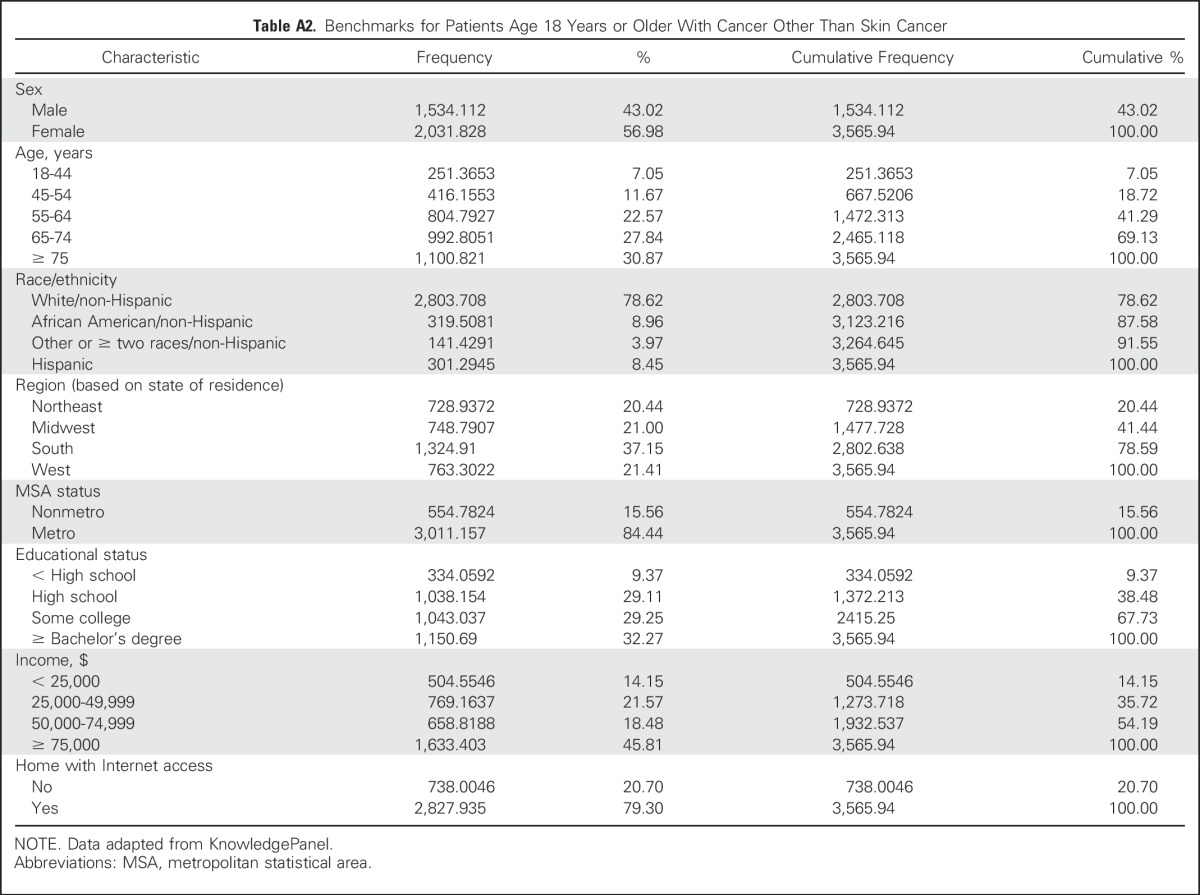

Table A2.

Benchmarks for Patients Age 18 Years or Older With Cancer Other Than Skin Cancer

Fig A1.

Creation of a scale measure of comfort. As stated in the Methods section, a scaled measure of comfort was developed using the sum score of nine items (each scored from 1 to 4). These nine items inquired regarding different situations “where someone might wish to use your medical records, after removal of identifying data like your name and date of birth.” The nine situations included: local hospital interested in providing people with information about how they might benefit from its program to prevent cancer; local hospital interested in making sure patients with cancer are getting the right treatments; local hospital interested in marketing itself to nearby patients for cancer treatments; researchers at a university conducting a study about cancer; drug company that will use the information to help guide the development of new treatments for cancer; drug company interested in understanding which patients with cancer benefit from a drug it produces; drug company interested in marketing new drugs and other health care products to patients with cancer; insurance company interested in making sure patients with cancer receive the most recommended care; and insurance company interested in determining which cancer treatments are eligible for coverage or reimbursement. Item internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) and factor analysis were used to confirm a one-factor solution. Exploratory factor analysis suggested that 60% of the pooled variance for the nine items was explained by a single factor, with only marginal improvement with additional factors. The scale was unimodal, with a mean of 26.9, and ranged from the scale floor of 9 to its ceiling of 36. (A) Scree plot; (B) variance explained.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the Greenwall Foundation and National Cancer Institute Grant No. R01 CA201356 (Re.J.).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Reshma Jagsi, Aaron Sabolch, Angela R. Bradbury

Financial support: Reshma Jagsi

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Perspectives of Patients With Cancer on the Ethics of Rapid-Learning Health Systems

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Reshma Jagsi

Employment: University of Michigan

Honoraria: International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics, Institute for Medical Education

Consulting or Advisory Role: Eviti, Baptist Health

Research Funding: AbbVie (Inst)

Kent A. Griffith

No relationship to disclose

Aaron Sabolch

No relationship to disclose

Rochelle Jones

No relationship to disclose

Rebecca Spence

No relationship to disclose

Raymond De Vries

No relationship to disclose

David Grande

Expert Testimony: Pfizer (I)

Angela R. Bradbury

Research Funding: Myriad Genetics, Hill-Rom (I)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Hill-Rom (I)

REFERENCES

- 1.King J, Patel V, Furukawa MF. Physician Adoption of Electronic Health Record Technology to Meet Meaningful Use Objectives: 2009-2012: ONC Data Brief No. 7. Washington, DC: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schilsky RL, Michels DL, Kearbey AH, et al. Building a rapid learning health care system for oncology: The regulatory framework of CancerLinQ. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2373–2379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, et al (eds): Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2013. [PubMed]

- 4. Selby JV, Krumholz HM: Ethical oversight: Serving the best interests of patients. Hastings Cent Rep S34-S36, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5. Kass NE, Faden RR, Goodman SN, et al: The research-treatment distinction: A problematic approach for determining which activities should have ethical oversight. Hastings Cent Rep S4-S15, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Larson EB. Building trust in the power of “big data” research to serve the public good. JAMA. 2013;309:2443–2444. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damschroder LJ, Pritts JL, Neblo MA, et al. Patients, privacy and trust: Patients’ willingness to allow researchers to access their medical records. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:223–235. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.016782. Jones RD, Sabolch AN, Aakhus E, et al: Patient perspectives on the ethical implementation of a rapid learning system for oncology care. J Oncol Pract 13:e163-e175, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelley M, James C, Alessi Kraft S, et al. Patient perspectives on the learning health system: The importance of trust and shared decision making. Am J Bioeth. 2015;15:4–17. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2015.1062163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nass SJ, Levit LA, Gostin LO (eds): Beyond the HIPAA Privacy Rule: Enhancing Privacy, Improving Health Through Research. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caine K, Hanania R. Patients want granular privacy control over health information in electronic medical records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20:7–15. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhopeshwarkar RV, Kern LM, O’Donnell HC, et al. Health care consumers’ preferences around health information exchange. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:428–434. doi: 10.1370/afm.1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bell EA, Ohno-Machado L, Grando MA: Sharing my health data: A survey of data sharing preferences of healthy individuals. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2014:1699-1708, 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Schwartz PH, Caine K, Alpert SA, et al. Patient preferences in controlling access to their electronic health records: A prospective cohort study in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(suppl 1):S25–S30. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3054-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grande D, Mitra N, Shah A, et al. The importance of purpose: Moving beyond consent in the societal use of personal health information. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:855–862. doi: 10.7326/M14-1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grande D, Mitra N, Shah A, et al. Public preferences about secondary uses of electronic health information. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1798–1806. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim KK, Joseph JG, Ohno-Machado L. Comparison of consumers’ views on electronic data sharing for healthcare and research. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22:821–830. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riordan F, Papoutsi C, Reed JE, et al. Patient and public attitudes towards informed consent models and levels of awareness of electronic health records in the UK. Int J Med Inform. 2015;84:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura M, Nakaya J, Watanabe H, et al. A survey aimed at general citizens of the US and Japan about their attitudes toward electronic medical data handling. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:4572–4588. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110504572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kass NE, Natowicz MR, Hull SC, et al. The use of medical records in research: What do patients want? J Law Med Ethics. 2003;31:429–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2003.tb00105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grande D, Asch DA, Wan F, et al. Are patients with cancer less willing to share their health information? Privacy, sensitivity, and social purpose. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:378–383. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.004820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abernethy AP, Etheredge LM, Ganz PA, et al. Rapid-learning system for cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4268–4274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.5478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. GfK Custom Research North America: Methodological papers, presentations, and articles on KnowledgePanel. http://www.knowledgenetworks.com/ganp/reviewer-info.html.

- 24. GfK Custom Research North America: KnowledgePanel design summary. http://www.knowledgenetworks.com/knpanel/docs/knowledgepanel(R)-design-summary-description.pdf.

- 25. GfK Custom Research North America: Institutional review board (IRB) support: GfK company information & confidentiality and privacy protections for KnowledgePanel panelists—Documentation for human subject review committees, 7/2013 update. http://www.knowledgenetworks.com/ganp/irbsupport/

- 26.Mavaddat N, Kinmonth AL, Sanderson S, et al. What determines self-rated health (SRH)? A cross-sectional study of SF-36 health domains in the EPIC-Norfolk cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:800–806. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.090845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.TRIAD Study Group The Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) study: A multicenter study of diabetes in managed care. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:386–389. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shea JA, Micco E, Dean LT, et al. Development of a revised health care system distrust scale. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:727–732. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0575-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Vries RG, Tomlinson T, Kim HM, et al. Understanding the public’s reservations about broad consent and study-by-study consent for donations to a biobank: Results of a national survey. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beecher HK. Ethics and clinical research. N Engl J Med. 1966;274:1354–1360. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196606162742405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maupin JE, Warren RC. Transformational medical education leadership: Ethics, justice and equity—The U. S. public health service syphilis study at Tuskegee provides insight for health care reform. Ethics Behav. 2012;22:501–504. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skloot R.The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. New York, NY: Crown Publishing; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Secko DM, Preto N, Niemeyer S, et al. Informed consent in biobank research: A deliberative approach to the debate. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:781–789. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim SY, Wall IF, Stanczyk A, et al. Assessing the public’s views in research ethics controversies: Deliberative democracy and bioethics as natural allies. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2009;4:3–16. doi: 10.1525/jer.2009.4.4.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]