Abstract

In recent years there is growing public awareness and increasing attention to young women with acute myocardial infarction (AMI), who represent an extreme phenotype. Young women presenting with AMI may develop coronary disease by different mechanisms and often have worse recoveries, with higher risk for morbidity and mortality compared with similarly aged men. The purpose of this cardiovascular perspective piece is to review recent studies of AMI in young women. More specifically, we emphasize differences in the epidemiology, diagnosis and management of AMI in young women (as compared with men) across the continuum of care, including their the pre-AMI, in-hospital and post-AMI periods, and highlight gaps in knowledge and outcomes that can inform the next generation of research.

There has been increasing attention to young women with acute myocardial infarction (AMI), as evidenced by two large international prospective studies1, 2 and several other published studies. In addition, recent national campaigns and evidence-based guidelines have focused on young women with AMI.3, 4 These investigations and efforts have significantly advanced our understanding of AMI in this population, yet important questions remain.

Young women with AMI have distinct features that are inherently unique from other populations.4–6 For example, young women may develop coronary artery disease (CAD) via different pathophysiologic mechanisms than men or older adults. They are more likely to experience disease of the coronary microvasculature,7, 8 spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD),9–11 or plaque erosion rather than plaque rupture.12, 13 Furthermore, young women have worse outcomes than age-matched men and older women, including higher in-hospital mortality,14–18 as well as short-19, 20 and long-term mortality following AMI.19, 21 These differences in outcomes are increasingly being described in populations throughout the world.17, 22–27 Moreover, although there has been an overall reduction in cardiovascular disease prevalence and AMI deaths in the general population, rates of AMI in young women have increased.20, 28 As such, there is an need to advance more effective awareness and treatment strategies specific to this population, as well as a comprehensive approach to improving outcomes for young women with AMI.

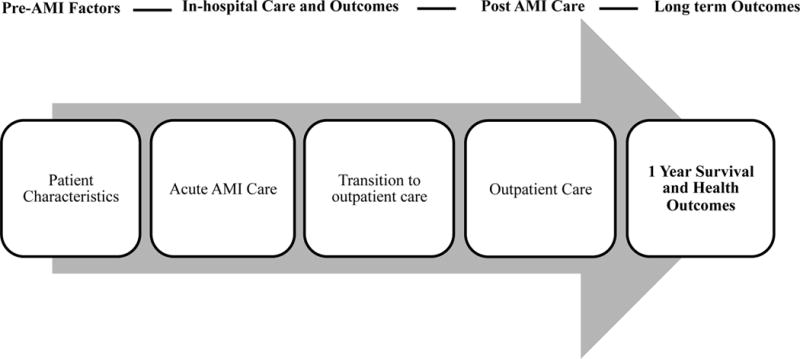

In this cardiovascular perspective piece, we describe contemporary studies that address the differences in the diagnosis and management of AMI in young women (as compared with men) across the continuum of care, including pre-AMI, in-hospital AMI care and post-AMI settings (Figure 1). We also focus on sex/gender bias and the biological, social, and contextual factors that contribute to poor outcomes. Finally, we highlight gaps in knowledge and outcomes that can inform the next generation of research – including potential mediators of sex differences in outcomes.

Figure 1.

Potential Mediators of Post AMI Outcomes among Young Women with AMI. Abbreviations: AMI=acute myocardial infarction.

Epidemiology

In recent years there has been an overall decrease in cardiovascular disease prevalence and AMI mortality in the general population, most likely due to improved awareness and the application of evidence-based therapies for coronary disease.29 However, rates of AMI in young women have increased.20, 28 Two recent population-based studies on trends in AMI hospitalization and early mortality post AMI have revealed important findings. Using data from the National Inpatient Sample of US hospital discharges, Gupta and colleagues examined temporal trends of hospitalization rates and in-hospital mortality by sex among young patients with AMI.28 They showed that from 2001 – 2010, there was either no change or a small absolute increase in hospitalization rates for young women with AMI. Although they observed declining in-hospital mortality rates for young women, in all time-periods, these rates were consistently higher than for similar aged men with AMI.28 A similar study conducted by Izadnegahdar and colleagues examined sex differences in temporal trends of AMI hospitalization rates and 30-day mortality in a Canadian setting.20 Results indicated that age-standardized AMI rates declined similarly in both women and men from 2000 – 2009. However, trends differed according to age, wherein young women aged <55 years had an increase in incidence. While 30-day mortality rates decreased similarly for both sexes, young women had higher rates of death than young men in all years.20 Contemporary studies also indicate that young women (<65 years of age) are more likely to be readmitted to the hospital following AMI than men.30 More specifically, young women have nearly a 2-fold higher risk of 30-day readmission following AMI.30 Even after sequential adjustment for a range of potentially explanatory variables between sexes, young women still have a higher risk of readmission than similarly aged men. In summary, most studies suggest that young women have persistently higher rates of mortality and re-hospitalization from AMI.31

AMI in Young Women

Two contemporary prospective studies have, in particular, informed our recent understanding of outcomes, and predictors of outcomes, among young women with AMI. The VIRGO study (Variation in Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young Acute Myocardial Infarction patients) was initiated in August of 2008, with enrollment completed by January of 2012.1 VIRGO was a prospective study to investigate key demographic, clinical, psychosocial, biological, behavioral, and environmental determinants of the prognosis of young women and men with AMI and to identify potential targets for interventions to improve their outcomes and/or clinical course. The study enrolled 3,572 patients aged 18–55 years with AMI from 103 sites across the United States, 24 sites in Spain and 3 sites in Australia; and used a 2:1 female: male enrollment ratio to enrich the study’s inclusion of young women. The VIRGO methodology and design have been previously described.1 The study sought to explore a broad range of outcomes including mortality, all-cause readmission, and adverse health status (including psychosocial sequela of illness).

The GENESIS-PRAXY study (GENdEr and Sex determInantS of cardiovascular disease: From bench to beyond-Premature Acute Coronary Syndrome)2 was developed in January of 2009, with enrollment completed in April 2013. This study enrolled 1,576 patients with acute coronary syndrome aged 18–55 years from 24 centers across Canada, 1 center in the United States and 1 center in Switzerland. The study’s design and methods have previously been described.2 GENESIS-PRAXY aimed to identify and quantify the behavioral, environmental, and biological factors in premature AMI, highlighting differences observed between men and women. The main focus of this study was healthcare utilization, access to care, presentation (both clinically and anatomically on angiogram), post-AMI prognosis, and interactions between sex/gender with genetic determinants of premature AMI.

Pre-AMI Factors

On presentation for AMI, young women have higher rates of traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes and obesity, and are more likely to have prior cardiovascular disease including congestive heart failure, peripheral artery disease and stroke.17, 19, 28, 32–36 Despite this, young women are significantly less likely than men to report having a clinician discuss heart disease or risk factor modification prior to their AMI.32, 37 In addition to cardiovascular risk factors and disease, young women also have a higher prevalence of comorbidities including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal failure, autoimmune disorders, cancer, and psychiatric disorders.32, 33,34 Moreover, nearly a third of young women with premature AMI have a history of hypertensive disorder of pregnancy on initial presentation38 in contrast to population-level estimates of 2–8% of all pregnancies.38 Social factors previously associated with adverse outcomes are also more prevalent among young women, including being unmarried and unemployed, and financial stress, in comparison to men.32, 33, 39, 40 Regarding health care access, while fewer young women with AMI (compared with men with AMI) are uninsured, they are more likely to report financial barriers to medication and healthcare services and are more likely to have government insurance (e.g. Medicare, Medicaid) as compared with private insurance.39, 41 Compared with men, women also are more likely than men to have a primary care provider, and as likely as men to have a specialist involved in their care.32

Pre-clinical health status also varies between young women and men. In young women, the most common prodromal symptom leading up to the AMI is fatigue.42 Additionally, in the month prior to presentation of AMI, young women have a poorer health status and worse psychosocial status than men. Specifically, women report worse physical/mental functioning, more angina, worse physical limitations, and a poorer quality of life prior to their AMI.32, 33 Moreover, they report both a higher rate of lifetime history of depression and depressive symptoms as well as poorer social supports, more anxiety and greater perceived stress at the time of an AMI.19, 32, 34, 41, 43–45

AMI Presentation

Chest pain is the most common presenting complaint for AMI in young women and men; however, young women are more likely to have atypical symptoms.16, 32, 46 Potentially because women do not recognize these symptoms as being signs of AMI, young women are more likely than men to delay seeking care, frequently presenting after 6 hours of symptom onset.32, 41, 46

Disease presentation is also different between the sexes; for example young women tend to have smaller infarcts as evidenced by lower levels of cardiac biomarkers, and are less likely to have ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).32, 44 In a study classifying phenotypes of AMI in the VIRGO cohort,47 1 in 8 women did not meet criteria for either type 1 (plaque erosion/rupture) or type 2 (myocardial oxygen supply-demand mismatch) AMI, according to the Universal Definition of MI. Moreover, SCAD, vasospasm, and coronary embolism accounted for only 1.5% of AMI’s in young women. Instead, the authors found that the mechanism of AMI was not known in 10% of women, and therefore proposed a new taxonomy that would allow for the identification and grouping of patients previously not captured by the current classification system; the VIRGO taxonomy is intended to inform future scientific investigations and clinical management aimed at improving outcomes for patients.47

In-hospital AMI Care and Outcomes

Compared with men, young women with AMI experience delays in reperfusion and are less likely to receive PCI and CABG, as well as aspirin, statins, and beta blockers on presentation to hospital.17, 34, 40, 46, 48 More specifically, data from VIRGO and the GENESIS PRAXY studies have demonstrated that young women with STEMI are less likely than men of similar age to receive reperfusion therapy and are more likely to have reperfusion delays.46,40 Of particular importance, women are more likely to exceed in-hospital and transfer time guidelines for PCI than men, and these differences persist following adjustment for important confounders.46 Women are also less likely than men to receive timely electrocardiography or fibrinolytic therapy.46 Clinical predictors of delayed diagnostic and therapeutic interventions include absence of chest pain, increased number of risk factors, anxiety, housework and feminine traits of personality (according to the BEM Sex-Role Inventory – including being softly spoken and gentle).40 In addition to in-hospital delays, young women experience a higher rate of bleeding following excess dosing of anticoagulant agents – a common practice among all young adults undergoing PCI.49 The delay in reperfusion and/or suboptimal acute therapies warrants community and professional education. Furthermore, excess bleeding in women post AMI represents an important opportunity to build awareness and implement strategies to reduce complications.

Post-AMI Care

Significant differences also exist in outpatient care for young women with AMI – particularly regarding secondary prevention. Several contemporary studies have demonstrated both sex and age disparities in guideline concordant medication treatment and adherence post AMI.18, 50–52 More specifically, women are less likely to be on optimal pharmaceutical therapy across all ages, however, the greatest disparity has been observed for young women aged under 55 years.52 Data from the VIRGO study demonstrates that women are also less likely to be referred for cardiac rehabilitation in the first month after AMI; also, among those referred, fewer women attend cardiac rehab, reporting financial barriers as a reason for non-participation.39 While there are similar rates of health insurance in young women and men, women report more financial barriers to medications and healthcare services, in general.36

Women report being less physically active in the first month following AMI and/or to meet American Heart Association (AHA) physical activity recommendations as compared with men.36, 53 Additionally young women are less likely to be taking statins at discharge and among those on statins, women are also less likely to be treated with a high intensity dose at 1-month post AMI, compared with men.36 Beyond immediate management and medications, women are less likely to be counseled by physicians about lifestyle choices. For example, although resuming sexual activity is an important aspect of recovery, young women are less likely than men to receive counseling in the first month after discharge for AMI,54 even though they report being more sexually active than men in the year before their event.

Long-Term Health Outcomes

Several studies have contributed to our understanding of health outcomes up to one year following AMI. Data from the VIRGO and GENESIS-Praxy studies demonstrate no sex differences in mortality and major adverse cardiac events (MACE; including ACS, PCI or CABG), which is in contrast to earlier studies.14, 15, 21 The low numbers of events at 1-year post AMI (i.e. between 1–3% for mortality; 8–9% for MACE) may be a limitation of recruitment inherent to observational registries with in-depth survey follow-up.31, 48 Work by Pelletier et al suggested that ‘feminine’ personality traits that are traditionally attributed to women (e.g. being shy and/or sensitive to needs of others), as well as social roles (e.g. housework responsibility) increase the risk of recurrent ACS over the period of 1-year following discharge.55 Regarding other clinical endpoints such as hospital readmission, contemporary data indicates that the risk of rehospitalization in women extends beyond the 30-day time period up to 1-year following AMI.30, 56 Lastly, building on data in the outpatient setting, young women also report more impaired sexual activity and/or incident sexual function problems than men in the year after discharge for AMI.57

Recovery, as measured by health status trajectories, are similar for men and women, however, women have significantly poorer scores than men on all health status domains at baseline and throughout the 12 month-period following AMI. For example, young women experience poorer mental/physical functioning, more angina, and a poorer quality of life,48 an effect which persists following adjustment. A study conducted by Leung-Yinko found that women report worse health related quality of life (HRQOL) than men over time post ACS, both in terms of mental and physical functioning.58 This study extended the field by showing that gender related factors such as femininity scores (described above) and housework responsibilities were more likely to be predictors of HRQOL than sex.58 In addition to having poorer functioning young women are less likely to return to work over a period of 12-months,59 and experience a higher risk of depression and stress in the year following AMI.43, 60, 61

Conclusions

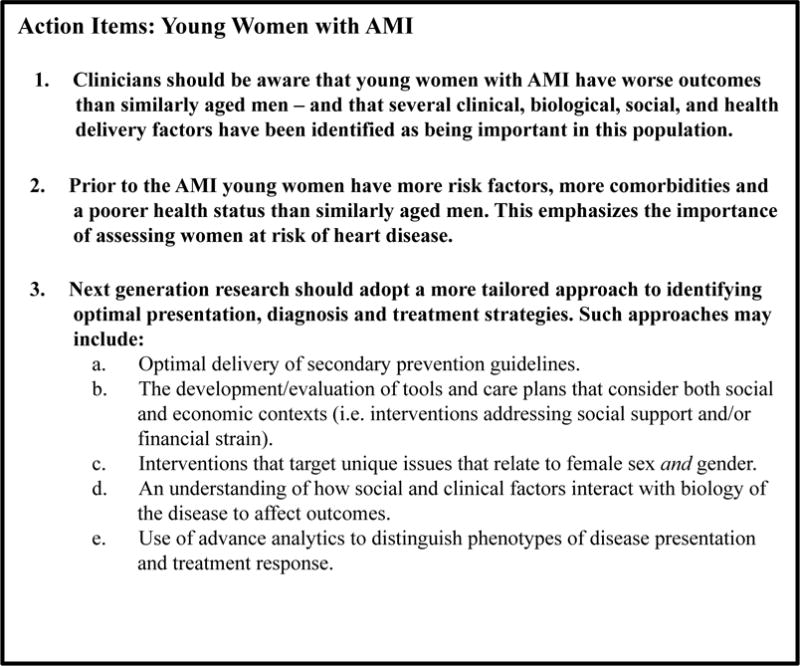

Contemporary studies, predominately from VIRGO and GENESIS PRAXY, have been fundamental in understanding a range of factors that underlie sex and gender differences between women and men with AMI, including differences in disease presentation, recognition and management, and referral and counseling to support recovery from AMI. These factors provide specific opportunities for targeted interventions aimed to improve morbidity and mortality in this population and to reduce sex/gender-based disparities. Still, more research is needed to understand how social and clinical factors interact with the biology of the disease to affect outcomes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Young Women with AMI – Action Items and Future Directions.

The next generation of research could adopt a more tailored approach to identifying optimal prevention, diagnosis and treatment strategies. Such approaches may include gender- and sex-specific counseling and engagement, optimal delivery of secondary prevention guidelines, and use of advanced analytics to distinguish phenotypes of disease presentation and treatment response. Attention should be given to the development and evaluation of tools and care plans that consider the social and economic context in which AMI is occurring in young women. For example, interventions that address factors such as social support61 and financial stress39 – both of which can increase treatment burden and reduce opportunities to achieve optimal cardiovascular health – are needed. Future interventions should also consider the unique issues that relate to female sex and gender,62–64 which may influence recovery.

Until recently, young women with AMI had been under-recognized in cardiology, frequently grouped together with the larger population of people with AMI who do not share similar characteristics or outcomes. Yet young women with AMI are an extreme phenotype in heart disease that require tailored approaches to clinical care and focused research. Several important studies have informed our understanding of health disparities in this population. Recent conferences such as the National Policy and Science Summit on Women’s Cardiovascular Disease, sponsored by WomenHeart: The National Coalition for Women with Heart Disease,65 for the first time focused on the health of young women with and at risk for heart disease.65 Important progress has been made; yet there remain important opportunities to advance outcomes in this population.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: Dr Krumholz is supported by grant U01 HL105270-05 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr Dreyer is supported by an Early Career Fellowship funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Dr Spatz is supported by grant K12HS023000 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Mentored Career Development Program. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and/or PCORI. No other relevant sources of funding are reported.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Drs Krumholz and Spatz report receiving support from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop and maintain performance measures used in public reporting programs. Dr Krumholz reports receiving research agreements from Medtronic and from Johnson & Johnson (Janssen), through Yale University, to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing and chairing a cardiac scientific advisory board for UnitedHealth. Dr. Krumholz is also the recipient of a grant from the Food and Drug Administration and Medtronic to develop methods for post-market surveillance of medical devices; is a participant/participant representative of the IBM Watson Health Life Sciences Board; and is the founder of Hugo, a personal health information platform. No other relevant disclosers are reported.

References

- 1.Lichtman JH, Lorenze NP, D’Onofrio G, Spertus JA, Lindau ST, Morgan TM, Herrin J, Bueno H, Mattera JA, Ridker PM, Krumholz HM. Variation in recovery: Role of gender on outcomes of young ami patients (virgo) study design. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:684–693. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.928713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pilote L, Karp I. Genesis-praxy (gender and sex determinants of cardiovascular disease: From bench to beyond-premature acute coronary syndrome) Am Heart J. 2012;163:741–746. e742. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Heart Association. The Go Red for Women Campaign. Available at: http://www.goredforwomen.org. Accessed December 10, 2016.

- 4.Mehta LS, Beckie TM, DeVon HA, Grines CL, Krumholz HM, Johnson MN, Lindley KJ, Vaccarino V, Wang TY, Watson KE, Wenger NK, American Heart Association Cardiovascular Disease in Women, Special Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology CoE, Prevention CoC, Stroke N, Council on Quality of C, Outcomes R Acute myocardial infarction in women: A scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation. 2016;133:916–947. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckie T. Biopsychosocial determinants of health and quality of life among young women with coronary heart disease. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports. 2014;8:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levit RD, Reynolds HR, Hochman JS. Cardiovascular disease in young women: A population at risk. Cardiol Rev. 2011;19:60–65. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e31820987b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellasi A, Raggi P, Merz CN, Shaw LJ. New insights into ischemic heart disease in women. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74:585–594. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.74.8.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merz CN, Kelsey SF, Pepine CJ, Reichek N, Reis SE, Rogers WJ, Sharaf BL, Sopko G. The women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation (wise) study: Protocol design, methodology and feasibility report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1453–1461. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basso C, Morgagni GL, Thiene G. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: A neglected cause of acute myocardial ischaemia and sudden death. Heart. 1996;75:451–454. doi: 10.1136/hrt.75.5.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeMaio SJ, Jr, Kinsella SH, Silverman ME. Clinical course and long-term prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:471–474. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson EA, Ferraris S, Gress T, Ferraris V. Gender differences and predictors of mortality in spontaneous coronary artery dissection: A review of reported cases. J Invasive Cardiol. 2005;17:59–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falk E, Nakano M, Bentzon JF, Finn AV, Virmani R. Update on acute coronary syndromes: The pathologists’ view. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:719–728. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burke AP, Farb A, Malcom GT, Liang Y, Smialek J, Virmani R. Effect of risk factors on the mechanism of acute thrombosis and sudden coronary death in women. Circulation. 1998;97:2110–2116. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.21.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Every NR, Barron HV, Krumholz HM. Sex-based differences in early mortality after myocardial infarction. National registry of myocardial infarction 2 participants. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:217–225. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907223410401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaccarino V, Horwitz RI, Meehan TP, Petrillo MK, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Sex differences in mortality after myocardial infarction: Evidence for a sex-age interaction. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2054–2062. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.18.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canto JG, Rogers WJ, Goldberg RJ, Peterson ED, Wenger NK, Vaccarino V, Kiefe CI, Frederick PD, Sopko G, Zheng ZJ. Association of age and sex with myocardial infarction symptom presentation and in-hospital mortality. JAMA. 2012;307:813–822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nazzal C, Alonso FT. Younger women have a higher risk of in-hospital mortality due to acute myocardial infarction in chile. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2013;66:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bangalore S, Fonarow GC, Peterson ED, Hellkamp AS, Hernandez AF, Laskey W, Peacock WF, Cannon CP, Schwamm LH, Bhatt DL. Age and gender differences in quality of care and outcomes for patients with st-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2012;125:1000–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egiziano G, Akhtari S, Pilote L, Daskalopoulou SS, Investigators G Sex differences in young patients with acute myocardial infarction. Diabetic Medicine. 2013;30:e108–114. doi: 10.1111/dme.12084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Izadnegahdar M, Singer J, Lee MK, Gao M, Thompson CR, Kopec J, Humphries KH. Do younger women fare worse? Sex differences in acute myocardial infarction hospitalization and early mortality rates over ten years. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23:10–17. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaccarino V, Krumholz HM, Yarzebski J, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. Sex differences in 2-year mortality after hospital discharge for myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:173–181. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-3-200102060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon T, Mary-Krause M, Cambou JP, Hanania G, Gueret P, Lablanche JM, Blanchard D, Genes N, Danchin N, Investigators U Impact of age and gender on in-hospital and late mortality after acute myocardial infarction: Increased early risk in younger women: Results from the french nation-wide usic registries. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1282–1288. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrikopoulos GK, Tzeis SE, Pipilis AG, Richter DJ, Kappos KG, Stefanadis CI, Toutouzas PK, Chimonas ET, investigators of the Hellenic Study of AMI Younger age potentiates post myocardial infarction survival disadvantage of women. Int J Cardiol. 2006;108:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koek HL, de Bruin A, Gast F, Gevers E, Kardaun JW, Reitsma JB, Grobbee DE, Bots ML. Short- and long-term prognosis after acute myocardial infarction in men versus women. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radovanovic D, Erne P, Urban P, Bertel O, Rickli H, Gaspoz JM, Investigators AP Gender differences in management and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: Results on 20,290 patients from the amis plus registry. Heart. 2007;93:1369–1375. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.106781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen YJL, Smith M, Pan H, Collins R, Peto R, Chen Z, for the COMMIT/CCS-2 collaborative group Sex differences in hospital mortality following acute myocardial infarction in china: Findings from a study of 45 852 patients in the commit/ccs-2 study. Heart Asia. 2011;3:104–110. doi: 10.1136/heartasia-2011-010003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng X, Dreyer RP, Hu S, Spatz ES, Masoudi FA, Spertus JA, Nasir K, Li X, Li J, Wang S, Krumholz HM, Jiang L, China PCG. Age-specific gender differences in early mortality following st-segment elevation myocardial infarction in china. Heart. 2015;101:349–355. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta A, Wang Y, Spertus JA, Geda M, Lorenze N, Nkonde-Price C, D’Onofrio G, Lichtman JH, Krumholz HM. Trends in acute myocardial infarction in young patients and differences by sex and race, 2001 to 2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spatz ES, Beckman AL, Wang Y, Desai NR, Krumholz HM. Geographic variation in trends and disparities in acute myocardial infarction hospitalization and mortality by income levels, 1999–2013. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:255–265. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dreyer RP, Ranasinghe I, Wang Y, Dharmarajan K, Murugiah K, Nuti SV, Hsieh AF, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM. Sex differences in the rate, timing and principal diagnoses of 30-day readmissions in younger patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2015;132:158–166. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pelletier R, Choi J, Winters N, Eisenberg MJ, Bacon SL, Cox J, Daskalopoulou SS, Lavoie KL, Karp I, Shimony A, So D, Thanassoulis G, Pilote L, Investigators G-P Sex differences in clinical outcomes after premature acute coronary syndrome. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:1447–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bucholz EM, Strait KM, Dreyer RP, Lindau ST, D’Onofrio G, Geda M, Spatz ES, Beltrame JF, Lichtman JH, Lorenze NP, Bueno H, Krumholz HM. Sex differences in young patients with acute myocardial infarction: A virgo study analysis. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2016 doi: 10.1177/2048872616661847. pii:2048872616661847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dreyer RP, Smolderen KG, Strait KM, Beltrame JF, Lichtman JH, Lorenze NP, D’Onofrio G, Bueno H, Krumholz HM, Spertus JA. Gender differences in pre-event health status of young patients with acute myocardial infarction: A virgo study analysis. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2015 doi: 10.1177/2048872615568967. pii:2048872615568967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi J, Daskalopoulou SS, Thanassoulis G, Karp I, Pelletier R, Behlouli H, Pilote L, Investigators G-P Sex- and gender-related risk factor burden in patients with premature acute coronary syndrome. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.07.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Z, Fang J, Gillespie C, Wang G, Hong Y, Yoon PW. Age-specific gender differences in in-hospital mortality by type of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:1097–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu Y, Zhou S, Dreyer RP, Caulfield M, Saptz ES, Geda M, Lorenze N, Herbert P, D’Onofrio, Jackson E, Lichtman J, Bueno H, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM. Sex differences in lipid profiles and treatment utilization among young adults with acute myocardial infarction: Results from the virgo study. Am Heart J. 2017;183:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leifheit-Limson EC, D’Onofrio G, Daneshvar M, Geda M, Bueno H, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM, Lichtman JH. Sex differences in cardiac risk factors, perceived risk, and health care provider discussion of risk and risk modification among young patients with acute myocardial infarction: The virgo study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1949–1957. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDonald EG, Dayan N, Pelletier R, Eisenberg MJ, Pilote L. Premature cardiovascular disease following a history of hypertensive disorder of pregnancy. Int J Cardiol. 2016;219:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beckman AL, Bucholz EM, Zhang W, Xu X, Dreyer RP, Strait KM, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM, Spatz ES. Sex differences in financial barriers and the relationship to recovery after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003923. pii:003923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pelletier R, Humphries KH, Shimony A, Bacon SL, Lavoie KL, Rabi D, Karp I, Tsadok MA, Pilote L, Investigators G-P Sex-related differences in access to care among patients with premature acute coronary syndrome. CMAJ. 2014;186:497–504. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen SI, Wang Y, Dreyer R, Strait KM, Spatz ES, Xu X, Smolderen KG, Desai NR, Lorenze NP, Lichtman JH, Spertus JA, D’Onofrio G, Bueno H, Masoudi FA, Krumholz HM. Insurance and prehospital delay in patients </=55 years with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:1827–1832. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan NA, Daskalopoulou SS, Karp I, Eisenberg MJ, Pelletier R, Tsadok MA, Dasgupta K, Norris CM, Pilote L, Team GP Sex differences in prodromal symptoms in acute coronary syndrome in patients aged 55 years or younger. Heart. 2016 doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309945. pii:309945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu X, Bao H, Strait K, Spertus JA, Lichtman JH, D’Onofrio G, Spatz E, Bucholz EM, Geda M, Lorenze NP, Bueno H, Beltrame JF, Krumholz HM. Sex differences in perceived stress and early recovery in young and middle-aged patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2015;131:614–623. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smolderen KG, Strait KM, Dreyer RP, D’Onofrio G, Zhou S, Lichtman JH, Geda M, Bueno H, Beltrame J, Safdar B, Krumholz HM, Spertus JA. Depressive symptoms in younger women and men with acute myocardial infarction: Insights from the virgo study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001424. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leung Yinko SS, Maheswaran J, Pelletier R, Bacon SL, Daskalopoulou SS, Khan NA, Eisenberg MJ, Karp I, Lavoie KL, Behlouli H, Pilote L, investigators G-P Sex differences in health behavior change after premature acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2015;170:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.D’Onofrio G, Safdar B, Lichtman JH, Strait KM, Dreyer RP, Geda M, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM. Sex differences in reperfusion in young patients with st-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: Results from the virgo study. Circulation. 2015;131:1324–1332. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spatz ES, Curry LA, Masoudi FA, Zhou S, Strait KM, Gross CP, Curtis JP, Lansky AJ, Soares Barreto-Filho JA, Lampropulos JF, Bueno H, Chaudhry SI, D’Onofrio G, Safdar B, Dreyer RP, Murugiah K, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM. The variation in recovery: Role of gender on outcomes of young ami patients (virgo) classification system: A taxonomy for young women with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2015;132:1710–1718. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dreyer RP, Wang Y, Strait KM, Lorenze NP, D’Onofrio G, Bueno H, Lichtman JH, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM. Gender differences in the trajectory of recovery in health status among young patients with acute myocardial infarction: Results from the variation in recovery: Role of gender on outcomes of young ami patients (virgo) study. Circulation. 2015;131:1971–1980. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gupta A, Chui P, Zhou S, Spertus JA, Geda M, Lorenze N, Lee I, G DO, Lichtman JH, Alexander KP, Krumholz HM, Curtis JP. Frequency and effects of excess dosing of anticoagulants in patients </=55 years with acute myocardial infarction who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (from the virgo study) Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hawkins NM, Scholes S, Bajekal M, Love H, O’Flaherty M, Raine R, Capewell S. The uk national health service: Delivering equitable treatment across the spectrum of coronary disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:208–216. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koopman C, Vaartjes I, Heintjes EM, Spiering W, van Dis I, Herings RM, Bots ML. Persisting gender differences and attenuating age differences in cardiovascular drug use for prevention and treatment of coronary heart disease, 1998–2010. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3198–3205. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smolina K, Ball L, Humphries KH, Khan N, Morgan SG. Sex disparities in post-acute myocardial infarction pharmacologic treatment initiation and adherence: Problem for young women. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8:586–592. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.001987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Minges KESK, Owen N, Dunstan DW, Camhi SM, Lichtman JH, Geda M, Dreyer RP, Bueno H, Beltrame JF, Curtis JP, Krumholz HM. Gender differences in physical activity following acute myocardial infarction in younger adults: A prospective, observational study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;24:192–203. doi: 10.1177/2047487316679905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lindau ST, Abramsohn EM, Bueno H, D’Onofrio G, Lichtman JH, Lorenze NP, Mehta Sanghani R, Spatz ES, Spertus JA, Strait K, Wroblewski K, Zhou S, Krumholz HM. Sexual activity and counseling in the first month after acute myocardial infarction among younger adults in the united states and spain: A prospective, observational study. Circulation. 2014;130:2302–2309. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pelletier R, Khan NA, Cox J, Daskalopoulou SS, Eisenberg MJ, Bacon SL, Lavoie KL, Daskupta K, Rabi D, Humphries KH, Norris CM, Thanassoulis G, Behlouli H, Pilote L, Investigators G-P Sex versus gender-related characteristics: Which predicts outcome after acute coronary syndrome in the young? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dreyer RP, Dharmarajan K, Kennedy K, Jones PG, Vaccarino V, Murugiah K, Nuti SV, Smolderen KG, Buchanan DM, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM. Sex differences in 1-year all cause rehospitalization in patients after acute myocardial infarction. A prospective observational study. Circulation. 2017 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024993. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lindau ST, Abramsohn E, Bueno H, D’Onofrio G, Lichtman JH, Lorenze NP, Sanghani RM, Spatz ES, Spertus JA, Strait KM, Wroblewski K, Zhou S, Krumholz HM. Sexual activity and function in the year after an acute myocardial infarction among younger women and men in the united states and spain. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:754–764. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leung Yinko SS, Pelletier R, Behlouli H, Norris CM, Humphries KH, Pilote L, investigators G-P Health-related quality of life in premature acute coronary syndrome: Does patient sex or gender really matter? J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000901. pi:e000901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dreyer RP, Xu X, Zhang W, Du X, Strait KM, Bierlein M, Bucholz EM, Geda M, Fox J, D’Onofrio G, Lichtman JH, Bueno H, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM. Return to work after acute myocardial infarction: Comparison between young women and men. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:S45–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu X, Bao H, Strait KM, Edmondson DE, Davidson KW, Beltrame JF, Bueno H, Lin H, Dreyer RP, Brush JE, Spertus JA, Lichtman JH, D’Onofrio G, Krumholz HM. Perceived stress after acute myocardial infarction: A comparison between young and middle-aged women versus men. Psychosom Med. 2017;79:50–58. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bucholz EM, Strait KM, Dreyer RP, Geda M, Spatz ES, Bueno H, Lichtman JH, D’Onofrio G, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM. Effect of low perceived social support on health outcomes in young patients with acute myocardial infarction: Results from the virgo (variation in recovery: Role of gender on outcomes of young ami patients) study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001252. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pelletier R, Ditto B, Pilote L. A composite measure of gender and its association with risk factors in patients with premature acute coronary syndrome. Psychosom Med. 2015;77:517–526. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rossi AM, Pilote L. Let’s talk about sex…And gender! Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:S100–101. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.002660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pilote L, Humphries KH. Incorporating sex and gender in cardiovascular research: The time has come. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30:699–702. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wood SF, Mieres JH, Campbell SM, Wenger NK, Hayes SN, Scientific Advisory Council of WomenHeart: The National Coalition for Women with Heart D Advancing women’s heart health through policy and science: Highlights from the first national policy and science summit on women’s cardiovascular health. Womens Health Issues. 2016;26:251–255. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]