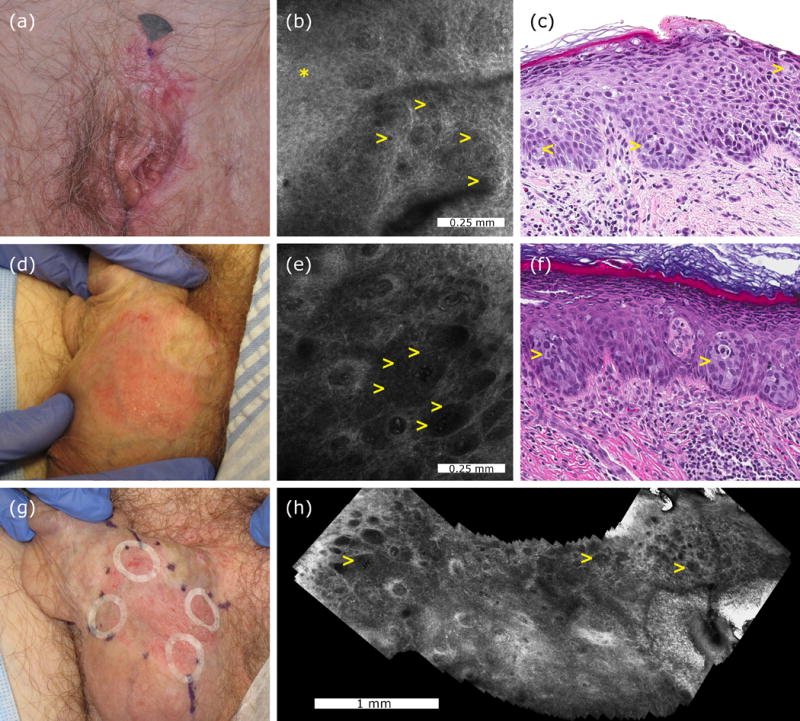

Figure 1.

Representative cases of a confocal false-negative extramammary Paget disease, and a confocal true-positive extramammary Paget disease. Clinical appearance of a vulvar recurrent extramammary Paget disease (case 2, panel a). Confocal examination of the mons pubis was interpreted as negative although after reevaluation focal dark holes (yellow arrowheads) were identified in the stratum spinosum (asterisk) (b). Histologically, case 2 showed scattered Paget cells (yellow arrowheads) in the inflamed and spongiotic epidermis (H&E, 20× magnification, panel c). Clinical appearance of a scrotal extramammary Paget disease prior to treatment (case 4, panel d). Confocal examination revealed multiple target cells (yellow arrowheads) with bright centre and peripheral dark halo forming nests at the dermoepidermal junction (e). Histological examination showed large cells with pale cytoplasm forming nests (yellow arrows) in the lower epidermis confirming the diagnosis of extramammary Paget disease (H&E, 20× magnification, panel f). Adhesive paper rings were placed at 12, 3, 6 and 9 o’clock to improve confocal navigation, and later moved to adjacent areas to cover the entire margins and to reduce sampling bias (g). Confocal videomosaic taken at the dermoepidermal junction captured inside one paper ring to facilitate identification of large nests of Paget cells (yellow arrows) over a larger field of view (h).