Abstract

The transcription of photosynthesis genes encoded by the plastid genome is mainly mediated by a prokaryotic-type RNA polymerase called plastid-encoded plastid RNA polymerase (PEP). Standard PEP-dependent promoters resemble bacterial sigma-70-type promoters containing the so-called -10 and -35 elements. On the other hand, an unusual light- and stress-responsive promoter (psbD LRP) that is regulated by a 19-bp AAG-box immediately upstream of the -35 element has been mapped upstream of the psbD-psbC operon in some angiosperms. However, the occurrence of the AAG-box containing psbD LRP in plant evolution remains elusive. We have mapped the psbD promoters in eleven embryophytes at different evolutionary stages from liverworts to angiosperms. The psbD promoters were mostly mapped around 500–900 bp upstream of the psbD translational start sites, indicating that the psbD mRNAs have unusually long 5′-UTR extensions in common. The -10 elements of the psbD promoter are well-conserved in all embryophytes, but not the -35 elements. We found that the AAG-box sequences are highly conserved in angiosperms and gymnosperms except for gnetaceae plants. Furthermore, partial AAG-box-like sequences have been identified in the psbD promoters of some basal embryophytes such as moss, hornwort, and lycophyte, whereas liverwort has the standard PEP promoter without the AAG-box. These results suggest that the AAG-box sequences of the psbD LRP may have evolved from a primitive type of AAG-box of basal embryophytes. On the other hand, monilophytes (ferns) use another type of psbD promoter composed of a distinct cis-element upstream of the potential -35 element. Furthermore, we found that psbD expression is not regulated by light in gymnosperms or basal angiosperms, although they have the well-conserved AAG-box sequences. Thus, it is unlikely that acquisition of the AAG-box containing psbD promoter is directly associated with light-induced transcription of the psbD-psbC operon. Light- and stress-induced transcription may have evolved independently and multiple times during terrestrial plant evolution.

Keywords: psbD LRP, chloroplast, promoter, evolution, stress

Introduction

Chloroplasts in plant and algal cells are semiautonomous organelles that have their own genome and gene expression system, reflecting their cyanobacterial origin. Chloroplast transcription is mediated by two distinct RNA polymerase systems, a prokaryotic multi-subunit RNA polymerase (PEP) whose core subunits are encoded by chloroplast genomes and single-subunit bacteriophage-type RNA polymerases (NEP) that are encoded by the nuclear genome (Hess and Börner, 1999; Liere et al., 2011; Yagi and Shiina, 2012, 2014; Liebers et al., 2017). The PEP core enzyme consists of four major subunits, designated as α, β, β′, and β″" subunits, which are homologous to bacterial subunits. Another dissociable subunit called a sigma factor allows the core enzyme to initiate transcription from the specific promoters. Multiple sigma factor genes have been identified in embryophytes (Tanaka et al., 1997; Morikawa et al., 1999; Fujiwara et al., 2000; Hara et al., 2001; Kasai et al., 2004; Kubota et al., 2007; Kanazawa et al., 2013), and they play specific roles in transcriptional regulation in response to developmental and/or environmental cues (reviewed by Kanamaru and Tanaka, 2004; Shiina et al., 2005; Schweer et al., 2010; Börner et al., 2015; Chi et al., 2015). Standard PEP-dependent promoters resemble bacterial sigma-70 type promoters containing -10 (TATAAT) and -35 (TTGACA) elements, reflecting their bacterial origin. NEP recognizes distinct types of promoters containing a core YRTA motif (Hess and Börner, 1999; Liere and Maliga, 1999; Liere et al., 2004; Börner et al., 2015). PEP transcribes mainly photosynthesis genes in mature chloroplasts while NEP transcribes housekeeping genes in both chloroplasts and non-photosynthetic plastids (Allison et al., 1996; Hajdukiewicz et al., 1997). The functional coordination of PEP and NEP plays a critical role in plastid differentiation in angiosperms.

In contrast to angiosperms, chloroplasts of the green algae C. reinhardtii harbor a simple transcription system, which is dependent on PEP and a single sigma factor SIG1 (Bohne et al., 2006; Yagi and Shiina, 2014). No NEP has been identified in Chlamydomonas. It is considered that embryophytes have developed complex transcription systems to adapt to marked environmental stresses. However, the evolutionary process of chloroplast transcription systems in embryophytes remains largely elusive.

Most PEP-dependent genes are actively transcribed in green tissues including the leaves. The chloroplast run-on experiments demonstrated that PEP-dependent transcription is activated by high light compared to normal growth light (Baena-González et al., 2001). However, the accumulation of most PEP-dependent transcripts is not regulated by light/dark transitions or environmental stresses, possibly due to the extraordinary stability of their transcripts (Shiina et al., 1998; Hayes et al., 1999). The only exception is a psbD light-responsive promoter designated psbD LRP, which is located upstream of a psbD-psbC operon encoding D2 (PsbD) and CP47 (PsbC) subunits of the PSII reaction center complex (Christopher et al., 1992; Wada et al., 1994; Allison and Maliga, 1995; To et al., 1996; Hoffer and Christopher, 1997). Transcription from the psbD LRP is activated by not only high-irradiance light, but also various abiotic stresses, including salt, high osmolarity and heat (Nagashima et al., 2004) and circadian rhythm (Noordally et al., 2013). The psbD LRP contains unique signature sequences named the AAG-box, immediately upstream of the -35 element (Allison and Maliga, 1995; Kim and Mullet, 1995; To et al., 1996; Nakahira et al., 1998; Kim et al., 1999). The AAG-box is composed of two different repeat units (AAGT and GACC/T repeats). In vitro transcription assays from the psbD LRP revealed that both repeat motifs are important for transcription, but not the -35 element in barley or wheat (Nakahira et al., 1998; Kim et al., 1999). Furthermore, the AAGT repeat interacts with the sequence-specific DNA-binding protein AGF (Kim and Mullet, 1995; Nakahira et al., 1998; Kim et al., 1999). It has also been shown that the stress-responsive plastid sigma factor SIG5 directs the activation of the psbD LRP in Arabidopsis thaliana (Nagashima et al., 2004; Tsunoyama et al., 2004; Onda et al., 2008).

The psbD promoter mapped in Chlamydomonas has a well-conserved -10 element, but lacks the AAG-box and standard -35 element (Klein et al., 1992; Klinkert et al., 2005). In addition, nucleotide sequence comparison of the upstream regions of the psbD among embryophytes suggests that A. thaliana (angiosperm) and Pinus thunbergii (gymnosperm) have the psbD LRP in their genome, but not the other basal embryophytes Physcomitrella patens (moss) and Marchantia polymorpha (liverwort) (Kanazawa et al., 2013). These findings suggest that the psbD LRP may have emerged during the evolution of embryophytes. However, evolution of the psbD promoter remains elusive. In this study, we mapped the promoter region of the psbD-psbC operon in eleven embryophytes at different evolutionary stages from liverwort to angiosperm. The results suggest that AAG-box sequences of the psbD LRP in angiosperms and gymnosperms may have evolved from the partial AAG-box-like sequences detected in the psbD promoters of basic embryophytes such as moss, hornwort, and lycophyte, while monilophytes (ferns) use a distinct type of psbD promoter lacking the AAG-box. On the other hand, light-dependent psbD expression was not observed in gymnosperms or primitive angiosperms that possess the well-conserved AAG-box, suggesting that the AAG-box containing psbD promoter acquisition is unlikely to be associated with the occurrence of light-dependent psbD expression.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Condition

For primer extension analysis, A. thaliana, Adiantum capillus-veneris, P, patens, and M. polymorpha (Tak-1) were grown in the light in growth chambers at 22°C under 16-h-light/8-h-dark (80–100 μmol photons m-2 s-1). Other samples (Laurus nobilis, Ginkgo biloba, P. thunbergii, Equisetum hyemale, Psilotum nudum, and Lycopodium clavatum were collected from plants cultivated at Kyoto Botanical Garden. Leaf samples were collected in the daytime, and immediately frozen in liquid N2. Light-induced gene expression analysis was carried out with plants (A. capillus-veneris, C. revoluta, P. thunbergii, L. nobilis, A. thaliana) grown in the growth chambers at 22°C under 16-h-light/8-h-dark (80 μmol photons m-2 s-1). Plants were dark-adapted for 72 h, and then exposed to light of 180 μmol photons m-2 s-1 for 4 h in the growth chamber. Collected leaf samples were immediately frozen in liquid N2.

Light-induced gene expression analysis (Supplementary Figures S4–S8) was also carried out with a wide range of embryophytes at different evolutionary stages from moss to angiosperms grown in the growth chambers at 22°C under 16-h-light/8-h-dark (80 μmol photons m-2 s-1). Plants were dark-adapted for 72 h (D), and then illuminated (275 μmolm-2s-1) for up to 12 h (L). Osmotic stress was achieved by 250 mM mannitol treatment for 6 h to the detached leaves. Collected leaf samples were immediately frozen in liquid N2.

Arabidopsis thaliana wild-type Columbia ecotype and AtSIG5-overexpressing plants were germinated and grown on two layers of filter paper on the one-half Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium containing 0.8% (w/v) agar at 22°C with 16-h light (80 μmol photons m-2 s-1)/8-h dark cycles for 10 days. For salt and high osmotic stress treatments, the seedlings were transferred to one-half MS medium containing 250 mM NaCl or 250 mM mannitol, and incubated under light (80 μmol photons m-2 s-1) for 6–24 h. For low temperature treatment, the seedlings were incubated at 4°C for 6–24 h under light conditions of 50 μmol photons m-2 s-1. For light response experiments, the seedlings were dark adapted for 72 h (D) and illuminated for 4 h with white light (80 μmol photons m–2 s–1) or a blue LED light (50 μmol photons m-2 s-1) or a red LED light (50 μmol photons m-2 s-1).

Transgenic Plants

First strand cDNA of AtSIG5 was synthesized from total RNA prepared from Arabidopsis seedlings using AMV reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa). cDNA was amplified by PCR using KOD-plus-DNA polymerase (TOYOBO) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. To obtain an AtSIG5 overexpression construct under the control of CaMV 35S promoter, the GUS gene of the binary vector pBI121 was replaced with the AtSIG5 cDNA. The resulting constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens and used to transform the wild-type (Col-0) plants.

Total RNA Isolation, Primer Extension Analysis, and Northern Blot Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the leaves using the RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, United States) or TRIZOL® following the manufacturer’s instructions. The primer extension assays were performed on the total RNA using the Primer Extension System (Promega) with the AMV reverse transcriptase following the manufacturer’s instructions. Primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Primer extension products were analyzed on a 6% polyacrylamide-7 M urea sequencing gel. For northern blot analysis, total RNA samples (2 μg) were separated by denaturing agarose gelelectrophoresis. After capillary blotting onto Hybond-N nylon membrane, RNA gel blots were hybridized to the randomly primed DNA probes for psbA and psbD of each plant. The psbD UTR probe (-1085 to -726 of the psbD translation start codon) was designed to detect specifically the transcripts from the psbD LRP in Arabidopsis. The psbD and psbA coding region probes were designed to detect transcripts produced from all multiple promoters in the psbD-psbC operon. The AtSIG5 probe was also prepared using specific primers. The psbD UTR probes specific for each plant were also generated by using PCR primers.

Results

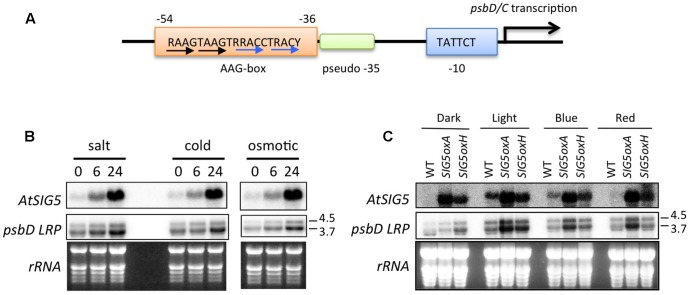

psbD LRP Transcription Is Dependent on SIG5

The psbD LRP is a unique PEP-dependent chloroplast promoter, which is responsible for the transcription of the psbD-psbC operon. The psbD-psbC operon is well-conserved among plants and cyanobacteria. Unlike standard PEP-dependent promoters composed of sigma-70 type -10 (TATAAT) and -35 (TTGACA) elements, it has been shown that psbD LRP activity is dependent on the upstream AAG-box in tobacco (Allison and Maliga, 1995), barley (Kim and Mullet, 1995), rice (To et al., 1996), and wheat (Nakahira et al., 1998; Figure 1A). On the other hand, the -35 element of the psbD LRP is not essential for transcription activity (To et al., 1996; Nakahira et al., 1998; Kim et al., 1999; Thum et al., 2001b). These findings suggest that the upstream AAG-box may take over the role of the pseudo -35 element in the psbD LRP.

FIGURE 1.

Involvement of AtSIG5 in transcription from the Arabidopsis psbD LRP. (A) Schematic structure of the psbD LRP in Arabidopsis. The psbD LRP consists of a well-conserved –10 element and an AAG-box upstream of a pseudo –35 element. The conserved 19-bp AAG-box that contains AAGT and GACC/T repeats (black and blue arrows, respectively) is indicated. R, A or G. Y, C or T. (B) Northern blot analysis of psbD LRP and AtSIG5 transcripts in A. thaliana treated with salt (250 mM NaCl), cold (4°C), and osmotic (250 mM mannitol) stresses for indicated time periods. Total RNAs (2 μg) were electrophoresed in a denatured gel, blotted, and hybridized to 32P-labeled gene-specific probes, psbD LRP UTR and AtSIG5 probes. The psbD probe was used to detect 3.7 and 4.5 kb mRNAs transcribed from the psbD LRP. Transcription of psbD LRP was significantly induced by abiotic stresses. (C) Light-dependent expression of psbD LRP transcripts in AtSIG5 overexpressing plants. The seedlings were dark adapted for 72 h (D) and illuminated for 4 h with white light (80 μmol photons m-2 s-1) or a blue LED light (50 μmol photons m-2 s-1) or a red LED light (50 μmol photons m-2 s-1).

Multiple promoters have been identified in the psbD-psbC operon (Hoffer and Christopher, 1997). The most upstream promoter (∼950 of the psbD translation start site) is a so-called psbD LRP that is specifically activated by blue light. To identify specifically mRNAs transcribed from the psbD LRP, we used a psbD UTR probe (-1085 to -726 of the psbD translation start codon) that is designed to be located upstream of the second promoter at -550 (Tsunoyama et al., 2004).

As shown in Figure 1B, the 4.5- and 3.7-kb transcripts from the psbD LRP were specifically detected by the psbD LRP UTR probe. As reported by Nagashima et al. (2004), various abiotic stresses including salt, cold, and hyperosmotic stresses induce transcription at the psbD LRP in a time-dependent manner (Figure 1B). Similarly, SIG5 transcription is activated by abiotic stresses. Previous reports (Nagashima et al., 2004; Tsunoyama et al., 2004) demonstrated that psbD LRP activity is abolished in AtSIG5-deficient mutants in Arabidopsis. In order to further define the role of AtSIG5 in transcription at the psbD LRP, we developed SIG5 overexpression lines (SIG5oxA and SIG5oxH) and examined transcription activity from the psbD LRP. The accumulation of psbD LRP transcripts was significantly increased by the overexpression of AtSIG5 in illuminated plants irrespective of the presence of white, blue, and red light, but only slightly in the dark (Figure 1C). These results clearly demonstrate that SIG5 specifically mediates transcription from the psbD LRP in the light. Photoreceptors including CRY1, CRY2, and PhyA have been shown to be involved in the light-induced expression of the psbD-psbC operon in Arabidopsis (Thum et al., 2001a), while AtSIG5 overexpression cannot activate transcription from the psbD LRP in the dark (Figure 1C). Taken together, photoreceptor-mediated signaling may modify SIG5 or SIG5 import in a light-dependent manner and activate transcription at the psbD LRP.

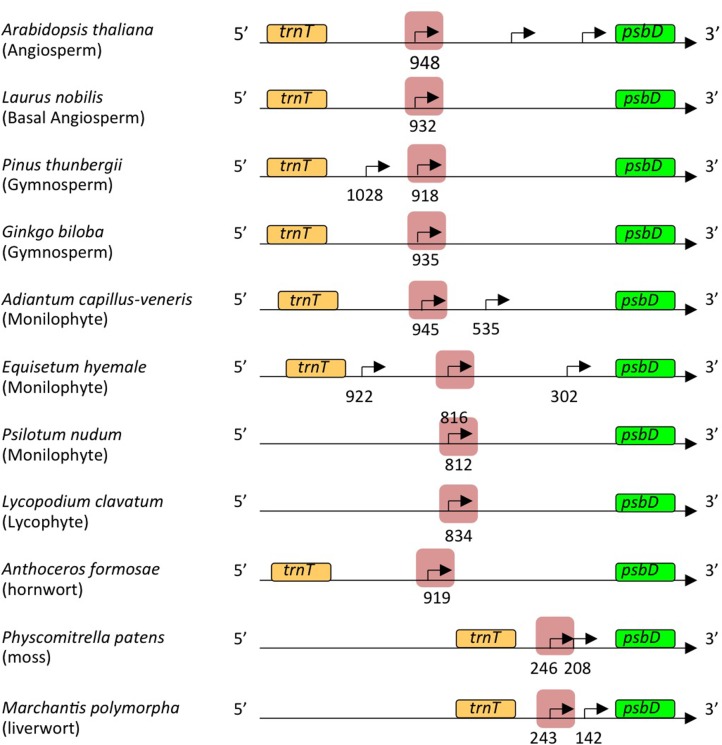

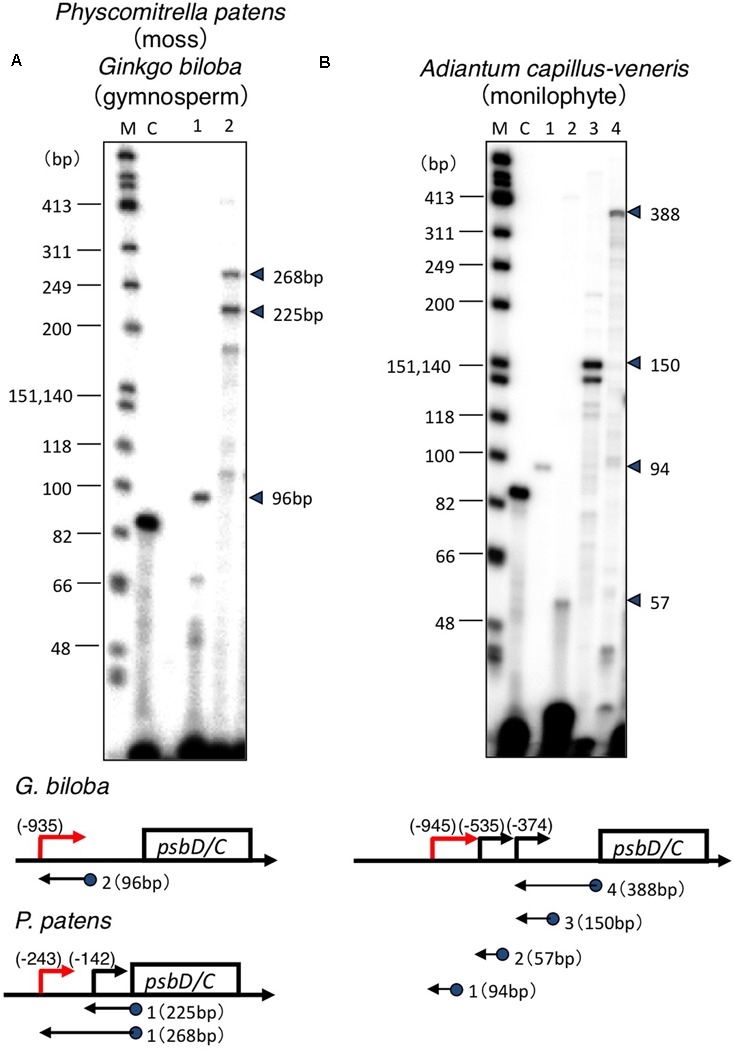

psbD Transcripts have Markedly Long 5′-UTRs in Common

Transcription initiation sites of the psbD-psbC operon have only been identified in some angiosperm model plants, including barley, wheat, rice, tobacco, and Arabidopsis (Yao et al., 1989; Christopher et al., 1992; Wada et al., 1994; To et al., 1996; Hoffer and Christopher, 1997), and green algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Klein et al., 1992). In order to address the evolutionary changes of psbD promoter structures, we mapped 5′-ends of psbD transcripts of eleven embryophytes at different evolutionary stages from liverworts to angiosperms using primer extension analysis (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S1, S2). Leaf samples were collected from plants grown in Kyoto Botanical Garden in the daytime, except for A. thaliana, A. capillus-veneris, P. patens, and M. polymorpha that were grown in the light in growth chambers. We estimated the size of primer extension products approximately by comparing their mobility profiles to single-strand DNA ladders. In order to determine the start sites as exactly as possible, we designed appropriate primers that produce primer extension products shorter than 300 bases. Next we searched for sequences similar to the conserved -10 sequences (TATTCT) of the psbD LRP in close proximity to the identified transcription initiation sites. Then, we aligned the deduced psbD promoter sequences with those of other plants using the -10 element as reference. In this study, we considered the psbD transcripts with the most upstream terminus as the primary transcripts, except for P. thunbergii and E. hyemale, which have another promoter upstream of the potential psbD LRP.

FIGURE 2.

Mapping of the 5′ ends of the psbD transcripts. Analysis of the psbD transcripts of the moss P. patens and primitive gymnosperm G. biloba (A), and monilophyte A. capillus-veneris (B) by primer extension assays. Primers used are indicated by numbers on the top of each lane. The size of the extension product is shown on the right. The position of primers and the size of the extension products are shown on the gene map. The deduced sites of the 5′-end of each transcript are shown as numbers in parentheses. Lane C shows an experiment with the control RNA and primer provided by the manufacturer that produces an 87-base primer extension product.

Transcription initiation sites from the psbD LRP have been mapped at 572, 610, 566, 905, and 948 bp upstream of the psbD translation start site of barley (Christopher et al., 1992), wheat (Wada et al., 1994), rice (To et al., 1996), tobacco (Yao et al., 1989), and Arabidopsis (Hoffer and Christopher, 1997), respectively. Similarly, 5′-ends of the psbD primary transcripts of the psbD-psbC operon were mapped at 800–900 bp upstream of the psbD gene in the most angiosperms including the basal angiosperm L. nobilis, gymnosperm P. thunbergii, primitive gymnosperm G. biloba, monilophyte (Leptosporangiate fern) A. capillus-veneris, monilophyte (Eusporangiate fern) P. nudum, monilophyte (Eusporangiate fern) E. hyemale, and lycophyte Huperzia lucidula (Figure 3). Furthermore, we found sequences similar to the psbD promoter of H. lucidula at the far upstream position (-919) of the psbD translation start site in Anthoceros formosae (hornwort). On the other hand, 5′-ends of the longest psbD transcripts of other bryophytes, P. patens (moss), and M. polymorpha (liverwort) are located at -246 and -243 of the psbD gene, respectively. These results indicate that psbD mRNAs have unusually long 5′-UTR extensions in common, except for mosses and liverworts. It is of note that intergenic distances between psbD and the upstream trnT are much shorter in mosses and liverworts compared with those of other plants.

FIGURE 3.

Representative maps of the psbD transcripts. The psbD transcript 5′-ends identified in Figure 2 and Supplementary Figures S1, S2 are shown by arrows. The psbD LRP-related promoters analyzed in this study are indicated by red shadows.

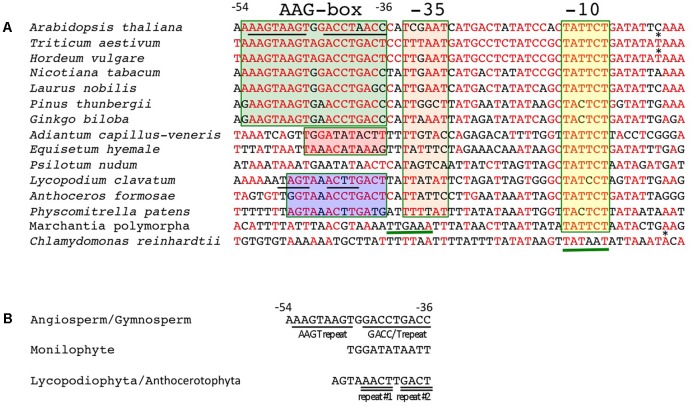

AAG-Box of the psbD LRP Is Highly Conserved among Angiosperms and Gymnosperms, and Partially Conserved in Lycophytes and Mosses

Next, we compared sequences immediately upstream of the psbD transcription initiation sites that were mapped in this and previous studies. The typical -10 elements (TATTCT) are well-conserved in all psbD promoters (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S2). Conversely, the potential -35 elements are less conserved among terrestrial plants and show weak similarity (less than ∼50%) to the consensus sequences (TTGACA). On the other hand, liverworts possess a typical sigma-70 type promoter with conserved -35 and -10 elements with 18-nt spacing. As expected, the AAG-box is well-conserved among angiosperms and gymnosperms. The consensus sequence of the AAG-box is “RAAGTAAGTRRACCTRACYY,” which contains an AAGT repeat and a GACC/T repeat. The AAG-box sequences are almost 80% identical in most gymnosperms and angiosperms, including the primitive gymnosperm G. biloba and basal angiosperm L. nobilis (Supplementary Table S2). We found that a 13-bp core sequence of the AAG-box is also highly conserved (∼85%) in lycophytes and hornworts, and partially conserved in mosses (69%), but not in liverworts. The AAG-box of lycophytes and hornworts harbors the GACC/T repeat-like sequences, but lacks the AAGT repeat (Figure 4B). On the other hand, neither the AAGT repeat nor GACC/T repeat are conserved in the psbD promoter of monilophytes (ferns). Instead, sequences upstream of the -35 element are well-conserved among standard monilophytes and P. nudum, but not in the primitive monilophyte E. hyemale (Figure 4B and Supplementary Figure S3). These results suggest that the AAG-box was acquired at a very early stage of embryophyte evolution, and is likely conserved in gymnosperms and angiosperms. On the other hand, monilophytes may have acquired another type of psbD promoter with a distinct cis element upstream of the -35 element.

FIGURE 4.

Conserved sequences of the AAG-box containing psbD promoters. (A) DNA sequences between –54 and +4 of the AAG-box containing psbD promoter transcription initiation sites are aligned among the plants analyzed. Transcription initiation sites identified in barley (Kim and Mullet, 1995) and wheat (Nakahira et al., 1998) are indicated by asterisks. Nucleotides that are identical to the wheat sequences are shown in red. The AAG-box in gymnosperms and angiosperms, fern-type upstream sequences, and AAG-box like sequences in basal land plants are indicated by green, red, and blue boxes, respectively. The –35 and –10 elements are indicated by orange and yellow boxes, respectively. The deduced –35 element in M. polymorpha sequences and –35 and –10 elements in C. reinhardtii are underlined. (B) Conserved sequences upstream of the –35 element. Characteristic repeats are underlined.

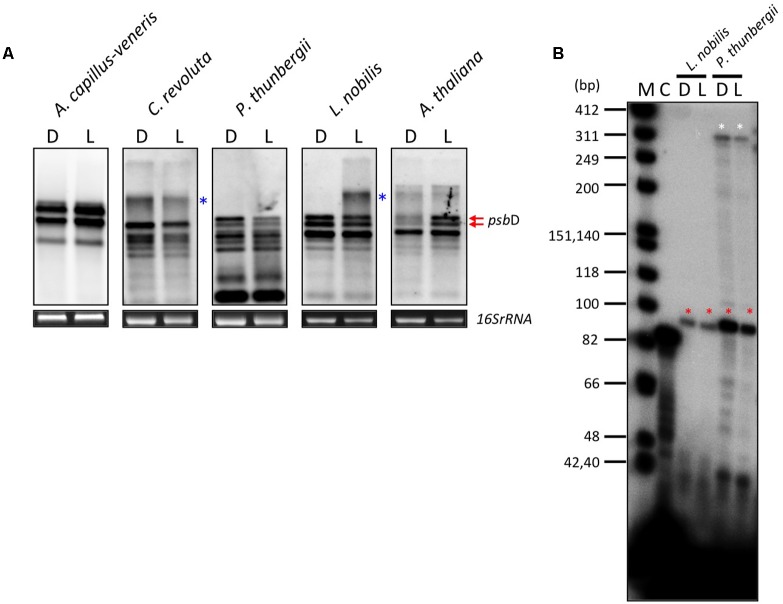

The AAG-Box Containing psbD Promoter Is not Associated with Light-Induced psbD Expression

In order to address whether the psbD LRP is responsible for light-induced transcription, we examined the light-induced expression of psbD transcripts in some embryophytes, including monilophytes, gymnosperms, and angiosperms. As shown in Figure 5A, psbD expression is clearly induced by light in A. thaliana (angiosperm). However, unexpectedly, no light-induced psbD expression was detected in L. nobilis (basal angiosperm), P. thunbergii (gymnosperm), or Cycas revoluta (primitive gymnosperm), although they all have a well-conserved AAG-box containing psbD promoter. Similarly, psbD expression is also not regulated by light in A. capillus-veneris (monilophyte), which does not have the conserved AAG-box in the psbD promoter. We further examined the light-mediated regulation of the AAG-box containing psbD promoter transcripts by primer extension analysis. As shown in Figure 5B, the abundance of the transcripts from the AAG-box containing psbD promoter was not regulated by light in L. nobilis or P. thunbergii (Figure 5B). These results suggest that the AAG-box containing psbD promoter is not directly associated with light-induced psbD expression.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of light on psbD transcription. (A) DIG-based northern blot analysis of psbD transcripts in monilophyte, gymnosperm, and angiosperm. Plants were dark-adapted for 72 h (D) and illuminated for 4 h (180 μmolm-2s-1; L). Previously characterized transcripts from the AAG-box containing psbD promoter are indicated by red arrows in Arabidopsis. The smear and extremely large bands (indicated by blue asterisks) represent large read-through transcripts of upstream genes. 16S rRNA was used as an RNA-loading control for the total RNA sample. (B) The AAG-box containing psbD promoter transcripts of L. nobilis and P. thunbergii were analyzed by primer extension assays. Plants were dark-adapted for 72 h (D) and illuminated for 4 h (180 μmolm-2s-1; L). Transcripts from the AAG-box containing psbD promoter are indicated by red asterisks. The white asterisks show transcripts from the uncharacterized promoter upstream of the AAG-box containing psbD promoter in P. thunbergii. Lane C shows an experiment with the control RNA and primer provided by the manufacturer that produces an 87-base primer extension product.

Moreover, we examined light- and osmotic stress-induced psbD expression in a wide range of plants. In angiosperms, light-induced psbD expression was detected in a number of eudicots (C. sativus, A. thaliana, and L. sativa) and monocots (wheat and maize), whereas psbD expression is not regulated by light in basal angiosperms except for C. glaber (Supplementary Figures S4–S6). It is to be noted that psbD expression is activated by long-term illumination (12 h) in C. glaber (Supplementary Figure S6). In contrast, the osmotic stress-induced expression of psbD was detected only in eudicots. Expression of psbD was not activated by osmotic stress in monocots and basal angiosperms except for C. glaber (Supplementary Figure S5, S6). Furthermore, neither light nor osmotic stress-induced psbD expression was detected in gymnosperms, Gingko and Cycas (Supplementary Figure S6). Although psbD expression was not activated by moderate light (180 μmolm-2s-1) in Pinus (Figure 5), high light exposure (245 μmolm-2s-1) induced transient expression of psbD (Supplementary Figure S6). It is of note that gymnosperms and basal angiosperms have a well-conserved AAG-box containing psbD promoter. On the other hand, psbD expression is induced by light and/or osmotic stress in some monilophytes that lack the typical AAG-box containing psbD promoter. In addition, light and salt stress barely affect psbA expression in any of the plants examined (Supplementary Figures S5–S8). These results indicate that light and salt stress-induced transcription has evolved independently and multiple times during land plant evolution. Furthermore, the AAG-box in the psbD promoter is unlikely to be directly associated with the occurrence of light and salt stress-induced psbD expression.

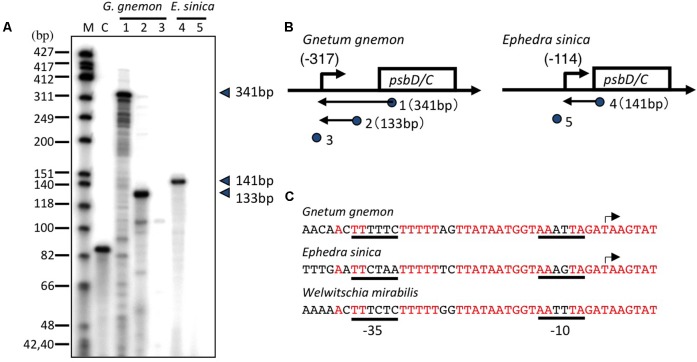

Gnetaceae Plants in Gymnosperms Have Lost the AAG-Box Containing psbD Promoter

Gnetaceae plants are a unique group of gymnosperms that have evolved a morphological system related to that of the angiosperms. The most upstream transcription initiation sites have been mapped at 317 and 114 bp upstream of the psbD translation start site of Gnetum gnemon and Ephedra sinica, respectively (Figures 6A,B). The psbD transcripts of gnetaceae have shorter 5′-UTR compared with the standard psbD transcripts in other plants. The upstream sequences of the psbD transcripts are well-conserved among gnetaceae. No AAG-box-like sequences are found upstream of the psbD transcripts in gnetaceae, whereas the gnetaceae psbD promoters possess -35- and -10-like sequences (Figure 6C). The similar sequences are also found upstream of the psbD-C operon of Welwitschia mirabilis. Moreover, AAG-box-like sequences have not been identified in the trnT-psbD intergenic regions of gnetaceae. We suggest that the AAG-box containing psbD promoter was lost in gnetaceae during their evolution. It would be very interesting to determine whether psbD expression is dependent on light in gnetaceaes.

FIGURE 6.

Mapping of the 5′ ends of the psbD transcripts in Gnetaceae plants. (A) The psbD LRP transcripts of the Gnetaceae plants G. gnemon (lanes 1–3) and E. sinica (lanes 4 and 5) were analyzed by primer extension assays. Primers used are indicated by numbers on the top of each lane. The size of the extension product is shown on the right. Lane C shows an experiment with the control RNA and primer provided by the manufacturer that produces an 87-base primer extension product. (B) Representative maps of the psbD transcripts. The psbD transcript 5′-ends identified by the primer extension assay are shown by arrows. The position of primers and the size of the extension products are shown on the gene map. The deduced sites of the 5′-end of each transcript are shown as numbers in parentheses. No transcript was detected with #3 and #5 primers. (C) DNA sequences between –37 and +7 of the AAG-box containing psbD promoter transcription initiation sites of G. gnemon and E. sinica are shown. The corresponding sequences of the psbD upstream region of Welwitschia mirabilis are also shown. Transcription initiation sites are indicated by arrows. Potential –35 and –10 elements are underlined.

Discussion

The psbD and psbC genes are organized in a psbD-psbC operon, which is well-conserved among plants and cyanobacteria. Transcription from the psbD-psbC operon is mediated solely by PEP in green tissues. Multiple transcriptional start sites (TSS) generating mRNAs with heterogeneous 5′ transcript leaders have been mapped on the psbD-psbC operon in several angiosperm plants, including tobacco (Yao et al., 1989), barley (Christopher et al., 1992), wheat (Wada et al., 1994), rice (To et al., 1996), and Arabidopsis (Hoffer and Christopher, 1997). Light activates the expression of some psbD-psbC mRNAs, whereas the accumulation of other mRNAs is not regulated by light. Analysis of the promoter sequences immediately upstream of the light-induced TSS identified an unusual PEP promoter consisting of a core promoter with a weakly conserved -35 element along with an upstream cis element termed the AAG-box (Figure 1A). This promoter is specifically activated by high-irradiance blue light and UV-A (Christopher and Mullet, 1994), and is designated as the psbD light-responsive promoter (psbD LRP) or psbD blue light-responsive promoter (psbD BLRP). As shown in Figure 1B, the psbD LRP is also activated by various environmental stresses (Nagashima et al., 2004). On the other hand, other light-insensitive promoters mapped on the psbD-psbC operon are standard PEP promoters composed of well-conserved -10 and -35 elements.

In order to investigate psbD LRP evolution, we mapped promoters responsible for the expression of the psbD-psbC operon by primer extension analysis in 11 embryophytes at different evolutionary stages from liverworts to angiosperms. We considered the psbD transcripts with the most upstream terminus as the primary transcripts, except for P. thunbergii and E. hyemale, which have another promoter upstream of the potential AAG-box containing psbD promoter. All psbD promoters identified at the most upstream mRNA terminus have the well-conserved -10 element (TATTCT) that is similar to the standard -10 element (TATAAT). On the other hand, the potential -35 elements of the psbD promoters are less conserved, suggesting the limited role of the -35 element in psbD promoter activity. In vitro transcription experiments have demonstrated that the -10 element is important for transcription from the AAG-box containing psbD promoter, but the -35 element is not essential for transcription in barley, rice, or wheat (To et al., 1996; Nakahira et al., 1998; Kim et al., 1999). It is considered that the -10 element is important for psbD promoter activity, but not the poorly conserved -35 element.

We found that the 19 bp AAG-box sequences of the psbD promoters are highly conserved among gymnosperms and angiosperms, including the basal angiosperm L. nobilis and primitive gymnosperm G. biloba. The consensus AAG-box sequence is “RAAGTAAGTRRACCTRACY,” which is at least 80% identical in gymnosperms and angiosperms. The AAG-box is composed of two repeat sequences: AAGT and GACC/T repeats. Extensive analyses of the AAG-box containing psbD promoter structure using in vitro transcription systems have revealed that both the AAGT and GACC/T repeats are important for AAG-box containing psbD promoter activity (Kim and Mullet, 1995; To et al., 1996; Nakahira et al., 1998). Moreover, the AAG-box is also partially conserved in basal land plants such as lycophytes, hornworts, and mosses. We identified the shorter conserved AAG-box-like sequences in H. lucidula (lycophyte) and A. formosae (hornwort). The AAG-box-like sequences in lycophyta and hornworts retain a partially conserved GACC/T repeat, but lack AAGT repeats. Deletion of the AAGT repeat resulted in only a partial reduction of in vitro transcription activity of the AAG-box containing psbD promoter in wheat, suggesting that the GACC/T repeat is sufficient to mediate AAG-box containing psbD promoter activity (Nakahira et al., 1998). Thus, the AAG-box-like sequences may act as a transcription activation element in the psbD promoters of basal land plants. Considering the highly conserved -10 element among bryophytes and angiosperms, it is likely that the last common ancestor of bryophytes and spermatophytes likely already possessed an AAG box-containing psbD LRP (Supplementary Figure S9). The AAG box may have developed to take over the function of the -35 element and support the high-level transcription activity of the AAG-box containing psbD promoter.

On the other hand, the AAG-box like sequences have not been identified in the psbD promoter of M. polymorpha (liverwort). The liverwort psbD promoter is composed of the typical -35 element (TTGAAA) and the -10 element (TATTCT) with standard spacing, suggesting that psbD is transcribed from a standard PEP promoter in liverworts. It is to be noted that the psbD promoter has a well-conserved -10 element, but lacks the AAG-box and standard -35 element in Chlamydomonas (Klein et al., 1992; Klinkert et al., 2005).

Monilophytes (ferns) have another type of psbD promoter that lacks the conserved AAG-box. Instead, 11-bp sequences upstream of the potential -35 element are well-conserved among standard (A. capillus-veneris) and primitive (P. nudum) monilophytes. However, it remains elusive whether the conserved sequences upstream of the psbD transcription stat site in monilophytes is required for psbD transcription. Interestingly, gnetaceae plants in gymnosperms have lost the AAG-box-containing psbD LRP, suggesting that the AAG-box containing psbD promoter is not essential for plant development.

It has also been shown that an AAG-box-binding factor (AGF) specifically binds to the AAGT repeat, that it is partially associated with the GACC/T repeats (Kim and Mullet, 1995; Kim et al., 1999), and that it activates transcription from the AAG-box containing psbD promoter (Wada et al., 1994; Kim and Mullet, 1995; Allison and Maliga, 1995; To et al., 1996; Nakahira et al., 1998; Kim et al., 1999). PTF1 (plastid transcription factor 1) is a basic helix-loop-helix DNA-binding protein, which binds to the AAG box and is involved in transcription from the psbD LRP in Arabidopsis (Baba et al., 2001). However, close orthologs of the Arabidopsis PTF1 have only been found in angiosperms, suggesting that PTF1 is responsible for AAG-box-dependent transcription at the AAG-box containing psbD promoter in angiosperms. However, the role of AGF in the light-dependent transcription remains to be elucidated.

In addition, reverse genetic analysis of sigma factors revealed that the AAG-box containing psbD promoter is specifically recognized by SIG5 in Arabidopsis (Nagashima et al., 2004; Tsunoyama et al., 2004). Transcription from the AAG-box containing psbD promoter is likely to be mediated by SIG5 containing PEP and activated by AGF that binds to the AAG-box. However, overexpression of SIG5 cannot activate transcription from the AAG-box containing psbD promoter in the dark (Figure 1C). Furthermore, photoreceptors including CRY1, CRY2, and PhyA are involved in the light-induced expression of the psbD-psbC operon in Arabidopsis (Thum et al., 2001a). Taken together, photoreceptor-mediated signaling may modify SIG5 or SIG5 import into the chloroplasts in a light-dependent manner and activate transcription at the AAG-box containing psbD promoter.

SIG5 orthologs have been identified in a number of angiosperms. Moreover, SIG5 has been identified as a gene that was abundant when water availability was low in gymnosperm Pseudotsuga menziesii (Hess et al., 2016). Furthermore, SIG5 orthologs have been identified in P. patens (Ichikawa et al., 2008) and Selaginella moellendorffii (XP_002970534). It has been shown that PpSIG5 is involved in high-intensity light and circadian control of psbD expression in the moss P. patens (Ichikawa et al., 2004, 2008). Taken together, these results suggest that SIG5 plays a role in transcription from the psbD promoter consisting of the AAG-box or AAG-like element in embryophytes including mosses. On the other hand, an SIG5 ortholog was also identified in the liverwort M. polymorpha (Kanazawa et al., 2013). MpSIG5 is not necessary for light-dependent psbD expression in M. polymorpha (Kanazawa et al., 2013). MpSIG5 may have another role in chloroplast transcription in M. polymorpha that lacks the AAG-box containing psbD promoter. Furthermore, SIG5 orthologs have been identified in some charophytes such as K. flaccidum, but not in the green alga C. reinhardtii or in the primitive red alga C. merolae. It is likely that SIG5 was acquired in charophytes before the occurrence of AAG-box containing psbD promoter in basal embryophytes.

Transcripts from the AAG-box containing psbD promoter are characterized by a markedly long 5′-UTR. All AAG-box containing psbD promoter transcripts except for P. patens and M. polymorpha have a 5′-UTR longer than 500 nucleotides from the translation start site. Detailed mapping of the psbD transcripts in angiosperm plants revealed that no intron is present in the 5′-UTR and the AAG-box containing psbD promoter transcripts actually have a long 5′-UTR (Wada et al., 1994; Hoffer and Christopher, 1997; Kim et al., 1999). The 5′-UTR of chloroplast transcripts may be involved in the stability of the transcripts and/or efficiency of translation (Shiina et al., 1998). However, no conserved sequences have been identified in the 5′-UTR of embryophytes. Further characterization of the 5′-UTR would shed light on the role of the unusually long 5′-UTR of the AAG-box containing psbD promoter in most embryophytes,

This study suggest that the AAG-box containing psbD promoter appeared in basal embryophytes more than 450 million years ago, and the common ancestor of bryophytes and spermatophytes likely possessed an AAG box-containing psbD promoter. On the other hand, the -35 and -10 elements of the psbA and rbcL promoters are almost identical among liverworts and angiosperms (Supplementary Figure S10). It is suggested that ecological and/or physiological demands may have accelerated the evolution of the AAG-box containing psbD promoter in embryophytes. One of the unique characteristics of the AAG-box containing psbD promoter is light- and stress-induced transcription. However, extensive expression analysis of psbD in a variety of plants revealed that the light and/or stress-induced expression of the psbD gene developed independently in several plants. Thus, it is unlikely that that light and/or stress responses of the AAG-box containing psbD promoter are directly associated with AAG-box containing psbD promoter evolution. Recent studies demonstrated that ABA and the circadian rhythm regulate chloroplast AAG-box containing psbD promoter activity via the activation of SIG5 (Noordally et al., 2013; Yamburenko et al., 2015; Belbin et al., 2017) Further analysis of the role of the AAG-box containing psbD promoter in chloroplasts may shed light on AAG-box containing psbD promoter evolution.

Author Contributions

TS, SS, SM, and YN designed research. SS, MN, ShK, SaK, and YI performed research. TS, SS, and MN analyzed data. TS, SS, and MN wrote the paper. SS and MN have contributed equally to this work.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Kyoto Botanical Garden for co-operation for plant sample collection. We also thank Dr. H. Tobe and Dr. M. H. Sato for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by JSPS and MEXT Grants- in-Aid for Scientific Research to TS (25291065, 15K14553, 15H01236, 17H05728, and 17H03968) and YN (15K14912), a grant from the Mitsubishi Foundation to TS, and a grant for high-priority study from Kyoto Prefectural University.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2017.01186/full#supplementary-material

FIGURE S1 | Mapping of the 5′ ends of the psbD transcripts psbD transcripts were isolated from liverwort M. polymorpha (A), lycophyte H. lucidula (B), and monilophyte P. nudum (C). Primers used are indicated by numbers on the top of each lane. The size of the extension product is shown on the right. The position of primers and the size of the extension products are shown on the gene map. The deduced sites of the 5′-end of each transcript are shown as numbers in parentheses. Lane Xs show the results of unrelated samples. Lane C shows an experiment with the control RNA and primer provided by the manufacturer that produces an 87-base primer extension product.

FIGURE S2 | Mapping of the 5’ ends of the psbD transcripts psbD transcripts were isolated from monilophyte E. hyemale (A), gymnosperm P. thunbergii (B), and angiosperm L. nobilis (C). Primers used are indicated by numbers on the top of each lane. The size of the extension product is shown on the left in (A) and on the right in (B,C). The position of primers and the size of the extension products are shown on the gene map. The deduced sites of the 5′-end of each transcript are shown as numbers in parentheses. Lane C shows an experiment with the control RNA and primer provided by the manufacturer that produces an 87-base primer extension product.

FIGURE S3 | A comparison of the potential psbD promoter sequences in monilophytes DNA sequences upstream of the psbD transcription initiation site of A. capillus-veneris and corresponding sequences of three other leptosporangiate ferns are compared with the psbD promoter sequences of two primitive ferns (P. nudum and E. hyemale). Transcription initiation sites identified in this study are indicated by asterisks. Nucleotides that are identical to the Adiantum sequences are shown in red. The monilophytes-type upstream conserved sequences are indicated by a green box. The -35 and -10 elements are indicated by orange and yellow boxes, respectively.

FIGURE S4 | Northern blot analysis of psbD and psbA transcripts in eudicots. Plants were dark-adapted for 72 h (D) and illuminated for up to12 h (275 μmolm-2s-1; L). Osmotic stress was applied by 250 mM mannitol for 6 h. Light- or salt stress-induced psbD transcripts are indicated by red arrow heads. rRNA stained with EtBr was used as an RNA-loading control for the total RNA sample.

FIGURE S5 | Northern blot analysis of psbD and psbA transcripts in monocots. Plants were dark-adapted for 72 h (D) and illuminated for up to12 h (275 μmolm-2s-1; L). Osmotic stress was applied by 250 mM mannitol for 6 h. Light- or salt stress-induced psbD transcripts are indicated by red arrow heads. rRNA stained with EtBr was used as an RNA-loading control for the total RNA sample.

FIGURE S6 | Northern blot analysis of psbD and psbA transcripts in basal angiosperms. Plants were dark-adapted for 72 h (D) and illuminated for 12 h (275 μmolm-2s-1; L). Osmotic stress was applied by 250 mM mannitol for 6 h. Light- or salt stress-induced psbD transcripts are indicated by red arrow heads. rRNA stained with EtBr was used as an RNA-loading control for the total RNA sample.

FIGURE S7 | Northern blot analysis of psbD and psbA transcripts in gymnosperms. Plants were dark-adapted for 72 h (D) and illuminated for up to 12 h (275 μmolm-2s-1; L). Osmotic stress was applied by 250 mM mannitol for 6 h. Light- or salt stress-induced psbD transcripts are indicated by red arrow heads. rRNA stained with EtBr was used as an RNA-loading control for the total RNA sample.

FIGURE S8 | Northern blot analysis of psbD and psbA transcripts in monilophytes. Plants were dark-adapted for 72 h (D) and illuminated for up to 12 h (275 μmolm-2s-1; L). Osmotic stress was applied by 250 mM mannitol for 6 h. Light- or salt stress-induced psbD transcripts are indicated by red arrow heads. rRNA stained with EtBr was used as an RNA-loading control for the total RNA sample.

FIGURE S9 | Phylogenetic tree of AAG box. Alignments were undertaken with 19 bps sequences (from -54 to -36 of the transcription initiation site) of 18 plants from C. reinhardtii to A. thaliana.

FIGURE S10 | Comparion of psbA and rbcL promoters of terrestrial plants.

References

- Allison L. A., Maliga P. (1995). Light-responsive and transcription-enhancing elements regulate the plastid psbD core promoter. EMBO J. 14 3721–3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison L. A., Simon L. D., Maliga P. (1996). Deletion of rpoB reveals a second distinct transcription system in plastids of higher plants. EMBO J. 15 2802–2809. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba K., Nakano T., Yamagishi K., Yoshida S. (2001). Involvement of a nuclear-encoded basic helix-loop-helix protein in transcription of the light-responsive promoter of psbD. Plant Physiol. 125 595–603. 10.1104/pp.125.2.595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baena-González E., Baginsky S., Mulo P., Summer H., Aro E. M., Link G. (2001). Chloroplast transcription at different light intensities. Glutathione-mediated phosphorylation of the major RNA polymerase involved in redox-regulated organellar gene expression. Plant Physiol. 127 1044–1052. 10.1104/pp.010168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belbin F. E., Noordally Z. B., Wetherill S. J., Atkins K. A., Franklin K. A., Dodd A. N. (2017). Integration of light and circadian signals that regulate chloroplast transcription by a nuclear-encoded sigma factor. New Phytol. 213 727–738. 10.1111/nph.14176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohne A. V., Irihimovitch V., Weihe A., Stern D. B. (2006). Chlamydomonas reinhardtii encodes a single sigma70-like factor which likely functions in chloroplast transcription. Curr. Genet. 49 333–340. 10.1007/s00294-006-0060-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börner T., Aleynikova A. Y., Zubo Y. O., Kusnetsov V. V. (2015). Chloroplast RNA polymerases: Role in chloroplast biogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1847 761–769. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi W., He B., Mao J., Jiang J., Zhang L. (2015). Plastid sigma factors: their individual functions and regulation in transcription. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1847 770–778. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher D. A., Kim M., Mullet J. E. (1992). A novel light-regulated promoter is conserved in cereal and dicot chloroplasts. Plant Cell 1992 785–798. 10.1105/tpc.4.7.785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher D. A., Mullet J. E. (1994). Separate photosensory pathways co-regulate blue light/ultraviolet-A-activated psbD-psbC transcription and light-induced D2 and CP43 degradation in barley (Hordeum vulgare) Chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 104 1119–1129. 10.1104/pp.104.4.1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara M., Nagashima A., Kanamaru K., Tanaka K., Takahashi H. (2000). Three new nuclear genes, sigD, sigE and sigF, encoding putative plastid RNA polymerase sigma factors in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 481 47–52. 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01965-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajdukiewicz P. T., Allison L. A., Maliga P. (1997). The two RNA polymerases encoded by the nuclear and the plastid compartments transcribe distinct groups of genes in tobacco plastids. EMBO J. 16 4041–4048. 10.1093/emboj/16.13.4041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K., Morita M., Takahashi R., Sugita M., Kato S., Aoki S. (2001). Characterization of two genes, Sig1 and Sig2, encoding distinct plastid sigma factors(1) in the moss Physcomitrella patens: phylogenetic relationships to plastid sigma factors in higher plants. FEBS Lett. 499 87–91. 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02530-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes R., Kudla J., Gruissem W. (1999). Degrading chloroplast mRNA: the role of polyadenylation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24 199–202. 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01388-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess M., Wildhagen H., Junker L. V., Ensminger I. (2016). Transcriptome responses to temperature, water availability and photoperiod are conserved among mature trees of two divergent Douglas-fir provenances from a coastal and an interior habitat. BMC Genomics 17:682 10.1186/s12864-016-3022-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess W. R., Börner T. (1999). Organellar RNA polymerases of higher plants. Int. Rev. Cytol. 190 1–59. 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)62145-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffer P. H., Christopher D. A. (1997). Structure and blue-light-responsive transcription of a chloroplast psbD promoter from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 115 213–222. 10.1104/pp.115.1.213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa K., Shimizu A., Okada R., Satbhai S. B., Aoki S. (2008). The plastid sigma factor SIG5 is involved in the diurnal regulation of the chloroplast gene psbD in the moss Physcomitrella patens. FEBS Lett. 582 405–409. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa K., Sugita M., Imaizumi T., Wada M., Aoki S. (2004). Differential expression on a daily basis of plastid sigma factor genes from the moss Physcomitrella patens. Regulatory interactions among PpSig5, the circadian clock, and blue light signaling mediated by cryptochromes. Plant Physiol. 136 4285–4298. 10.1104/pp.104.053033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamaru K., Tanaka K. (2004). Roles of chloroplast RNA polymerase sigma factors in chloroplast development and stress response in higher plants. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 68 2215–2223. 10.1271/bbb.68.2215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa T., Ishizaki K., Kohchi T., Hanaoka M., Tanaka K. (2013). Characterization of four nuclear-encoded plastid RNA polymerase sigma factor genes in the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha: blue-light- and multiple stress-responsive SIG5 was acquired early in the emergence of terrestrial plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 54 1736–1748. 10.1093/pcp/pct119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai K., Kawagishi-Kobayashi M., Teraishi M., Ito Y., Ochi K., Wakasa K., et al. (2004). Differential expression of three plastidial sigma factors, OsSIG1, OsSIG2A, and OsSIG2B, during leaf development in rice. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 68 973–977. 10.1271/bbb.68.973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Mullet J. E. (1995). Identification of a sequence-specific DNA binding factor required for transcription of the barley chloroplast blue light-responsive psbD-psbC promoter. Plant Cell 7 1445–1457. 10.1105/tpc.7.9.1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Thum K. E., Morishige D. T., Mullet J. E. (1999). Detailed architecture of the barley chloroplast psbD-psbC blue light-responsive promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 274 4684–4692. 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein U., De Camp J. D., Bogorad L. (1992). Two types of chloroplast gene promoters in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89 3453–3457. 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinkert B., Schwarz C., Pohlmann S., Pierre Y., Girard-Bascou J., Nickelsen J. (2005). Relationship between mRNA levels and protein accumulation in a chloroplast promoter-mutant of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Mol. Genet. Genomics 274 637–643. 10.1007/s00438-005-0056-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota Y., Miyao A., Hirochika H., Tozawa Y., Yasuda H., Tsunoyama Y., et al. (2007). Two novel nuclear genes, OsSIG5 and OsSIG6, encoding potential plastid sigma factors of RNA polymerase in rice: tissue-specific and light-responsive gene expression. Plant Cell Physiol. 48 186–192. 10.1093/pcp/pcl050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebers M., Grübler B., Chevalier F., Lerbs-Mache S., Merendino L., Blanvillain R., et al. (2017). Regulatory shifts in plastid transcription play a key role in morphological conversions of plastids during plant development. Front. Plant Sci. 8:23 10.3389/fpls.2017.00023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liere K., Kaden D., Maliga P., Börner T. (2004). Overexpression of phage-type RNA polymerase RpoTp in tobacco demonstrates its role in chloroplast transcription by recognizing a distinct promoter type. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 1159–1165. 10.1093/nar/gkh285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liere K., Maliga P. (1999). In vitro characterization of the tobacco rpoB promoter reveals a core sequence motif conserved between phage-type plastid and plant mitochondrial promoters. EMBO J. 18 249–257. 10.1093/emboj/18.1.249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liere K., Weihe A., Börner T. (2011). The transcription machineries of plant mitochondria and chloroplasts: Composition, function, and regulation. J. Plant Physiol. 168 1345–1360. 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa K., Ito S., Tsunoyama Y., Nakahira Y., Shiina T., Toyoshima Y. (1999). Circadian-regulated expression of a nuclear-encoded plastid sigma factor gene (sigA) in wheat seedlings. FEBS Lett. 451 275–278. 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00593-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima A., Hanaoka M., Shikanai T., Fujiwara M., Kanamaru K., Takahashi H., et al. (2004). The multiple-stress responsive plastid sigma factor, SIG5, directs activation of the psbD blue light-responsive promoter (BLRP) in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 45 357–368. 10.1093/pcp/pch050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahira Y., Baba K., Yoneda A., Shiina T., Toyoshima Y. (1998). Circadian-regulated transcription of the psbD light-responsive promoter in wheat chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 118 1079–1088. 10.1104/pp.118.3.1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordally Z. B., Ishii K., Atkins K. A., Wetherill S. J., Kusakina J., Walton E. J., et al. (2013). Circadian control of chloroplast transcription by a nuclear-encoded timing signal. Science 339 1316–1319. 10.1126/science.1230397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onda Y., Yagi Y., Saito Y., Takenaka N., Toyoshima Y. (2008). Light induction of Arabidopsis SIG1 and SIG5 transcripts in mature leaves: differential roles of cryptochrome 1 and cryptochrome 2 and dual function of SIG5 in the recognition of plastid promoters. Plant J. 55 968–978. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03567.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweer J., Türkeri H., Kolpack A., Link G. (2010). Role and regulation of plastid sigma factors and their functional interactors during chloroplast transcription - recent lessons from Arabidopsis thaliana. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 89 940–946. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiina T., Allison L., Maliga P. (1998). rbcL Transcript levels in tobacco plastids are independent of light: reduced dark transcription rate is compensated by increased mRNA stability. Plant Cell 10 1713–1722. 10.1105/tpc.10.10.1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiina T., Tsunoyama Y., Nakahira Y., Khan M. S. (2005). Plastid RNA polymerases, promoters and transcription regulators in higher plants. Int. Rev. Cytol. 244 1–68. 10.1016/S0074-7696(05)44001-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Tozawa Y., Mochizuki N., Shinozaki K., Nagatani A., Wakasa K., et al. (1997). Characterization of three cDNA species encoding plastid RNA polymerase sigma factors in Arabidopsis thaliana: evidence for the sigma factor heterogeneity in higher plant plastids. FEBS Lett. 413 309–313. 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00906-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thum K. E., Kim M., Christopher D. A., Mullet J. E. (2001a). Cryptochrome 1, Cryptochrome 2, and Phytochrome A co-activate the chloroplast psbD blue light–responsive promoter. Plant Cell 13 2747–2760. 10.1105/tpc.010345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thum K. E., Kim M., Morishige D. T., Eibl C., Koop H.-U., Mullet J. E. (2001b). Analysis of barley chloroplast psbD light responsive promoter elements in transplastomic tobacco. Plant Mol. Biol. 47 353–366. 10.1023/A:1011616400264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To K., Cheng M., Suen D., Mon D., Chen L. O., Chen S. G. (1996). Characterization of the light-responsive promoter of rice chloroplast psbD-C operon and the sequence-specific DNA binding factor. Plant Cell Physiol. 37 660–666. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a028995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoyama Y., Ishizaki Y., Morikawa K., Kobori M., Nakahira Y., Takeba G., et al. (2004). Blue light-induced transcription of plastid-encoded psbD gene is mediated by a nuclear-encoded transcription initiation factor, AtSig5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 3304–3309. 10.1073/pnas.0308362101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada T., Tunoyama Y., Shiina T., Toyoshima Y. (1994). In Vitro analysis of light-induced transcription in the wheat psbD/C gene cluster using plastid extracts from dark-grown and short-term-illuminated seedlings. Plant Physiol. 104 1259–1267. 10.1104/pp.104.4.1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi Y., Shiina T. (2012). Evolutionary aspects of plastid proteins involved in transcription: the transcription of a tiny genome is mediated by a complicated machinery. Transcription 3 290–294. 10.4161/trns.21810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi Y., Shiina T. (2014). Recent advances in the study of chloroplast gene expression and its evolution. Front. Plant Sci. 5:61 10.3389/fpls.2014.00061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamburenko M. V., Zubo Y. O., Börner T. (2015). Abscisic acid affects transcription of chloroplast genes via protein phosphatase 2C-dependent activation of nuclear genes: repression by guanosine-3′-5′-bisdiphosphate and activation by sigma factor 5. Plant J. 82 1030–1041. 10.1111/tpj.12876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao W. B., Meng B. Y., Tanaka M., Sugiura M. (1989). An additional promoter within the protein-coding region of the psbD-psbC gene cluster in tobacco chloroplast DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 17 9583–9591. 10.1093/nar/17.23.9583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FIGURE S1 | Mapping of the 5′ ends of the psbD transcripts psbD transcripts were isolated from liverwort M. polymorpha (A), lycophyte H. lucidula (B), and monilophyte P. nudum (C). Primers used are indicated by numbers on the top of each lane. The size of the extension product is shown on the right. The position of primers and the size of the extension products are shown on the gene map. The deduced sites of the 5′-end of each transcript are shown as numbers in parentheses. Lane Xs show the results of unrelated samples. Lane C shows an experiment with the control RNA and primer provided by the manufacturer that produces an 87-base primer extension product.

FIGURE S2 | Mapping of the 5’ ends of the psbD transcripts psbD transcripts were isolated from monilophyte E. hyemale (A), gymnosperm P. thunbergii (B), and angiosperm L. nobilis (C). Primers used are indicated by numbers on the top of each lane. The size of the extension product is shown on the left in (A) and on the right in (B,C). The position of primers and the size of the extension products are shown on the gene map. The deduced sites of the 5′-end of each transcript are shown as numbers in parentheses. Lane C shows an experiment with the control RNA and primer provided by the manufacturer that produces an 87-base primer extension product.

FIGURE S3 | A comparison of the potential psbD promoter sequences in monilophytes DNA sequences upstream of the psbD transcription initiation site of A. capillus-veneris and corresponding sequences of three other leptosporangiate ferns are compared with the psbD promoter sequences of two primitive ferns (P. nudum and E. hyemale). Transcription initiation sites identified in this study are indicated by asterisks. Nucleotides that are identical to the Adiantum sequences are shown in red. The monilophytes-type upstream conserved sequences are indicated by a green box. The -35 and -10 elements are indicated by orange and yellow boxes, respectively.

FIGURE S4 | Northern blot analysis of psbD and psbA transcripts in eudicots. Plants were dark-adapted for 72 h (D) and illuminated for up to12 h (275 μmolm-2s-1; L). Osmotic stress was applied by 250 mM mannitol for 6 h. Light- or salt stress-induced psbD transcripts are indicated by red arrow heads. rRNA stained with EtBr was used as an RNA-loading control for the total RNA sample.

FIGURE S5 | Northern blot analysis of psbD and psbA transcripts in monocots. Plants were dark-adapted for 72 h (D) and illuminated for up to12 h (275 μmolm-2s-1; L). Osmotic stress was applied by 250 mM mannitol for 6 h. Light- or salt stress-induced psbD transcripts are indicated by red arrow heads. rRNA stained with EtBr was used as an RNA-loading control for the total RNA sample.

FIGURE S6 | Northern blot analysis of psbD and psbA transcripts in basal angiosperms. Plants were dark-adapted for 72 h (D) and illuminated for 12 h (275 μmolm-2s-1; L). Osmotic stress was applied by 250 mM mannitol for 6 h. Light- or salt stress-induced psbD transcripts are indicated by red arrow heads. rRNA stained with EtBr was used as an RNA-loading control for the total RNA sample.

FIGURE S7 | Northern blot analysis of psbD and psbA transcripts in gymnosperms. Plants were dark-adapted for 72 h (D) and illuminated for up to 12 h (275 μmolm-2s-1; L). Osmotic stress was applied by 250 mM mannitol for 6 h. Light- or salt stress-induced psbD transcripts are indicated by red arrow heads. rRNA stained with EtBr was used as an RNA-loading control for the total RNA sample.

FIGURE S8 | Northern blot analysis of psbD and psbA transcripts in monilophytes. Plants were dark-adapted for 72 h (D) and illuminated for up to 12 h (275 μmolm-2s-1; L). Osmotic stress was applied by 250 mM mannitol for 6 h. Light- or salt stress-induced psbD transcripts are indicated by red arrow heads. rRNA stained with EtBr was used as an RNA-loading control for the total RNA sample.

FIGURE S9 | Phylogenetic tree of AAG box. Alignments were undertaken with 19 bps sequences (from -54 to -36 of the transcription initiation site) of 18 plants from C. reinhardtii to A. thaliana.

FIGURE S10 | Comparion of psbA and rbcL promoters of terrestrial plants.