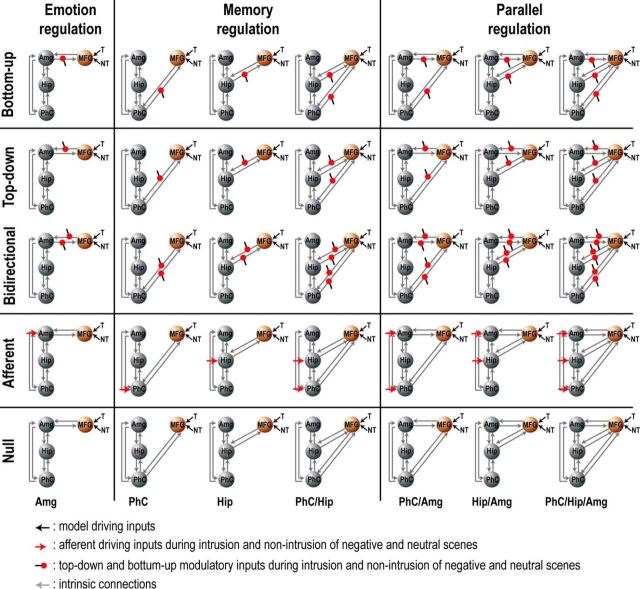

Figure 7.

DCM model space. DCM models were organized into two families. The first (the Modulatory family) divided the model space into five subgroups differing according to whether the intrinsic connection from the right MFG was modulated or not by No-Think trials (modeled as 3 s short epochs separately for Intrusion and Non-Intrusion of each emotion type). Subgroups 1–5 of this family (rows 1–5) either included modulation on bottom up (e.g., hippocampus to MFG, row 1), top-down (row 2), or bidirectional (row 3) connections; or no modulation, but variable afferent input to MTL regions from a source independent of MFG (row 4); or no modulation at all (row 5). The second family (the Regulation family) divided the model space into families according to modulatory targets. Subgroups 1–3 of this family (columns 1–3) include the Emotion Regulation family (left, amygdala modulation only), the Memory Regulation family (middle, modulation of hippocampus, parahippocampal cortex, or both), and the Parallel regulation family (right, modulation of amygdala, and other memory-related regions). After estimating all 35 models for each participant, we performed the group BMS as implemented in SPM12 (version DCM12 revision 4750; RRID:SCR_007037). This produces the exceedance probability (i.e., the extent to which each model is more likely than any other considered model) and expected posterior probability (i.e., the probability of a model generating the observed data). By positing connectivity relationships between MFG and these MTL structures in our DCM models, we do not presuppose direct anatomical connections (an assumption that DCM's analytical method does not require); rather, we are modeling the data to evaluate the existence of a (potentially) polysynaptic and directional causal influence of each region on the activity of others to which it is connected.