Abstract

In this manuscript we systematically reviewed 29 articles from 2010 to 2014 that addressed the association between borderline personality disorder (BPD) and intimate partner violence (IPV) perpetration, with particular attention paid to the role of perpetrator sex. Our primary objective was to provide a summary of (1) the operationalization and measurement of BPD and IPV, (2) mechanisms of the BPD–IPV association, and (3)the current understanding of the role of perpetrator sex related to BPD and IPV. We observed three distinct operational definitions of BPD which are measured in a variety of ways. IPV measurement tends to be more consistent. Further, emotion perception, impulsivity, attachment, and substance use are proposed mechanisms to explain the BPD IPV relation. The findings regarding potential perpetrator sex differences in the BPD–IPV association are mixed. Finally, we also provide recommendations for future research and clinical practice.

1. Introduction

1.1. Borderline personality disorder

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a severe psychological disorder found to impact approximately 1% of the general population (Coid et al., 2009; Lenzenweger, Lane, Loranger, & Kessler, 2007; Torgersen, Kringlen, & Cramer, 2001; Trull, Jahng, Tomko, Wood, & Sher, 2010), with at least one study finding BPD in as high as 6% of the general population (Grant et al., 2008). Individuals with BPD are overrepresented in clinical samples (e.g., Skodol et al., 2002), with one study estimating BPD in as high as 22% of its clinical sample (Korzekwa, Dell, Links, Thabane, & Webb, 2008). Individuals with BPD experience broad dysfunction across the domains of emotional functioning, behavior, relationships, and sense of self and considerable functional impairment across these domains (Bagge, Stepp, & Trull, 2005; Bagge et al., 2004; Bender et al., 2001; Holm & Severinsson, 2011; Skodol, Pagano, et al., 2005; Soloff, Lynch, & Kelly, 2002; Trull, Useda, Conforti, & Doan, 1997; Zweig-Frank & Paris, 2002). With suicide rates almost 50 times higher than the general population (Holm & Severinsson, 2011), BPD is a major public health problem of enormous scale and concern. BPD appears to be particularly impairing for women, who are estimated to be three-times more likely to receive a BPD diagnosis than men.

1.2. Intimate partner violence

A core feature of BPD is interpersonal dysfunction. One form of interpersonal dysfunction that has been observed in individuals with BPD is intimate partner violence (IPV) perpetration. Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a broad term, describing physical, sexual, or psychological harm inflicted by a current or former romantic partner or spouse (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). There is evidence that IPV in relationships may fall into distinct patterns; Johnson (2011) has described a distinction between situational couple violence and intimate terrorism. Situational couple violence, the most common form of IPV, refers to IPV engaged in by one or both partners when conflict escalates to a heated argument. In contrast, intimate terrorism refers to a pervasive pattern of coercive control of one partner by the other using a variety of forms of IPV. Representative community studies find that at least one in five couples in the United States experiences IPV each year (e.g., Schafer, Caetano, & Clark, 1998), with men and women exhibiting similar rates of IPV perpetration (Archer, 2001). Importantly, although rates of IPV perpetration are generally equivalent among men and women, recent evidence supports a gender imbalance in perpetration of intimate terrorism, with men being more than four times as likely to perpetrate this form of IPV than women (Johnson, Leone, & Xu, 2014). Regardless of biological sex, IPV perpetration is associated with increased risk of physical and mental health problems for its victims (e.g., injury, chronic pain, sexually transmitted diseases, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use; Afifi et al., 2009; Afifi, Henriksen, Asmundson, & Sareen, 2012; Campbell, 2002; Coker et al., 2002; Okuda et al., 2011). Evidence suggesting that men use more severe violence than do women is mixed (Hamberger & Guse, 2002), though men’s IPV perpetration has been shown to cause more severe injury than women’s IPV (Archer, 2001). Annual costs of IPV, including medical and mental health care services and lost work productivity, exceed $5.8 billion each year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003).

1.3. The current work

While the literature has examined the link between BPD and IPV victimization for well over a decade (e.g., Zanarini et al., 1999), empirical work focusing on the on relation between BPD and IPV perpetration is more recent, even though disturbances in interpersonal relationships and emotion regulation represent key features of BPD (e.g., Gunderson & Lyons-Ruth, 2008; Hill et al., 2008; Rosenthal et al., 2008). IPV perpetration may become increasingly relevant given recent changes to BPD diagnostic criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; APA, 2013). In order to obtain the diagnosis an individual must exhibit impairment in self-functioning and/or interpersonal functioning. In addition, the individual must demonstrate maladaptive personality functioning in the following domains: negative affectivity (e.g., emotional lability, anxiousness), separation insecurity, disinhibition (e.g., impulsivity and risk taking), and antagonism (e.g., hostility), all of which could theoretically heighten risk for IPV perpetration in individuals diagnosed with BPD.

The purpose of the current work is to provide a comprehensive review of empirical studies examining the association between BPD and related constructs (referred to as borderline personality pathology) and IPV perpetration. Previous reviews of risk factors for IPV perpetration have identified personality characteristics, including borderline personality pathology, as being associated with IPV perpetration (Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012; Schumacher, Feldbau-Kohn, Slep, & Heyman., 2001), and longitudinal research has shown that Cluster B (histrionic, narcissistic, and borderline) personality traits predict later perpetration of IPV (Ehrensaft, Cohen, & Johnson, 2006). The objectives of the present review are to:

-

1

Provide a nuanced summary of the extant literature examining the association between borderline personality pathology and IPV perpetration. Specifically, we decided to focus our summary on the following relevant constructs—operationalization of BPD in the BPD– IPV literature; severity and frequency of IPV, as it relates to BPD; and mechanisms of the BPD–IPV association.

-

2

Examine the scientific rigor of reviewed studies.

-

3

Provide recommendations for future research and clinical practice.

Further, given that women are historically overrepresented in the BPD literature, and men in the IPV perpetration literature, we intend to take sex into greater consideration than has been done in most previous studies of the BPD–IPV association. Specifically, we aim to:

-

4

Provide a framework for understanding the BPD–IPV association with respect to different sex configurations of the identified IPV perpetrator, including within dyads, where applicable.

2. Method

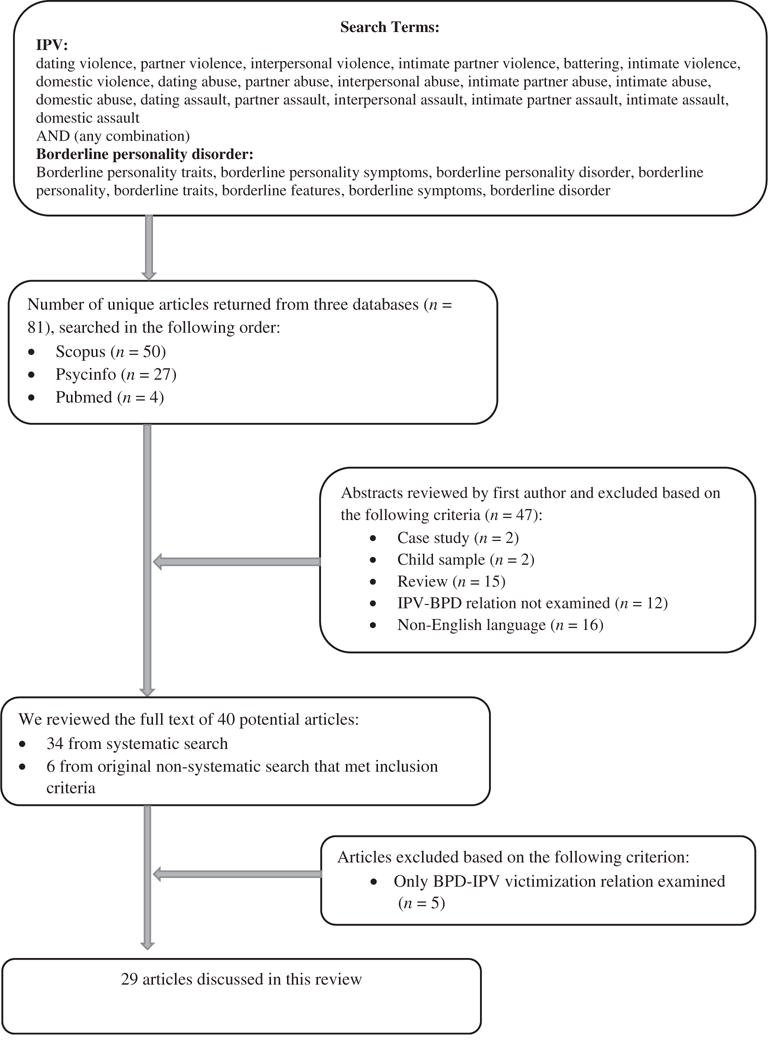

The authors conducted a preliminary, non-systematic search in order generate search terms and eligibility criteria for the systematic review. See Fig. 1 for a full outline of the eligibility criteria, as well as search and review procedures. In step 1 of the systematic search, the first author searched for articles that met any combination of both BPD (e.g., “borderline personality,” “borderline personality disorder,” “borderline disorder,” “borderline traits”) and IPV (e.g., “domestic violence,” “dating violence,” “battering”) search terms, as well as additional eligibility criteria (e.g., dates ranging from 2000 to 2014) in three commonly used databases (SCOPUS, PsycINFO, PubMed). This systematic search resulted in 81 unique abstracts. The first author then reviewed further to determine whether eligibility criteria were fully met (step 2). Out of these 81 abstracts, 34 were eligible (see Fig. 1 for ineligibility reasons). In the third step, the first four authors divided these 34 articles, as well as six from the original non-systematic search (that matched the keywords and eligibility) and reviewed the articles’ recruitment, methods, results, and discussion, entering relevant information into a table. In the final step, the first four authors met to decide which of these 40 articles to include in the final analysis, based on whether the constructs we aimed to examine (as outlined in our objectives) were addressed. From this discussion, the authors excluded five articles that solely examined the association between BPD and women’s IPV victimization, as well as six additional articles that did not include specific data on the BPD–IPV relation. We included 29 articles in the final analysis.

Fig. 1.

Search terms and search outcomes. This figure explains the steps in our systematic review process.

3. Results and discussion

The studies included in the final review are presented in Table 1 which provides descriptive information of each study’s recruitment location and method, measures of BPD and IPV, sample demographics, and brief review of relevant findings.

Table 1.

Summary of reviewed articles.

| Study | Sample characteristics | Study type and recruitment | IPV measure | BPD measure | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female samples–perpetration only (n =4) | ||||||

| Clift and Dutton (2011) | N = 914 college students currently or recently in dating relationships M age = 20.5 years Asian 48% Includes some lesbian women |

Cross-sectional: college sample | CIS (Straus. 1979) Violence scale Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory (PMWI; Tolman, 1989) |

Borderline personality organization scale (BPO; Oldham et al. 1985). | BPO significantly correlated with psychological aggression and with physical aggression. | |

| Fortunata and Kohn (2003) | N = 100 lesbian women in current relationships (33 IPV perpetrators and 67 non-perpetrators) Age range = 20–57 |

Cross-sectional: community sample | Modified CTS for research on lesbians | Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory (MCMI-III; Millon, 1994) | Perpetrators higher on borderline features than non-perpetrators. | |

| Goldens on et al. (2007) | Female offender group (FOG) n = 33 M age = 30.9 (SD = 7.8) White 42%, Af Amer 21%, Hispanic 15%, others 21% Clinical comparison group (CCG) n = 32, M age = 32 (SD = 9.1) White 625%, Af Amer 15.6%, Hispanic 6%, others 156% |

Cross-sectional; legal sample–mandated treatment for IPV | FOG–demographic report CCG–CTS-R & demographic report |

MCMI-III | FOG scored higher than CCG on CCG BPD, ASPD, attachment insecurity, and total trauma scores. | |

| Hughes et al. (2007) | N = 80 M age = 31.5 (SD = 9.3) Caucasian 78% |

Cross-sectional; legal sample–were mandated to engage in IPV intervention programming | CTS-2 | Borderline personality disorder (BPD) subscale of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4 (PDQ-4) | BPD mediated relationship between violence in childhood and physical aggression on the CTS-2 | |

| Female samples–female perpetration and victimization (n = 1) | ||||||

| Stuart et al. (2006) | N = 103 M age = 31.5 (SD = 9.6) White 78%, Af Amer 8%, Hispanic 8%, others 4% |

Cross-sectional; legal sample–referred to IPV intervention program | CTS-2 (both scales) | PDQ-4 (BPD and ASPD subscales) | Women court mandated to attend violence IPV intervention programs were 20.3 times more likely to have BPD compared to general U.S. population. | |

| Male and female samples–perpetration only (n = 5) | ||||||

| Newhill et al. (2012) | N = 1136 Male 57% White 69% |

Longitudinal–measures re-administered post-discharge every 10 weeks for one year; clinical–psychiatric patients recruited from inpatient units | Items adapted from CTS, arrest records, collateral info, patient self-report | Structured Interview for DSM-III-R Personality (SIDP-R) | BPD was a robust predictor of future violence, but no is longer a significant predictor after adjusting for effects of emotional dysregulation. | |

| Newhill et al. (2009) | N = 1136 Male 57% White 69% |

Longitudinal–follow-up post-discharge every 10 weeks for one year; clinical–psychiatric patients | Items adapted from CTS, arrest records, collateral info, patient self-report | SIDP-R | Individuals with BPD were more likely to commit seriously violent and aggressive acts. BPD remained a significant predictor after some indices of criminality and substance abuse were controlled for (but not when ASPD/psychopathy was entered). | |

| Weinstein et al. (2012) | N = 872 Female 43% Age range 55–64 |

Cross-sectional; community | CTS (psychological and physical subscales) | SIDP-R; multi-source assessment of personality pathology by participants and informants | BPD predicted aggression towards partner after controlling for gender, education, and past year alcohol dependence. Gender moderated this association; BPD symptoms more strongly related to women’s partner aggression than men’s. |

|

| Ross (2011) | N = 86 Female 35% M age = 30 (SD = 10.46) Caucasian 49% |

Cross-sectional; legal–IPV perpetrators referred for services | CTS-2 (physical aggression only); Controlling Behaviors Scale (Graham-Kevan & Archer, 2003) | PDQ-4 | BPD traits associated with domination-punishment and emotion regulation as motivation for IPV perpetration. BPD also linked to retaliation in men. Overall, in men, reasons for IPV linked mostly to personality traits (BPD and ASPD) whereas, in women, reasons for IPV linked to both personality and contextual variables. |

|

| Ross and Babcock (2009) | N = 124 couples Mean age = 32 years for men; 30 for women Caucasian 24% |

Cross-sectional; community–“couples experiencing conflict” | CTS-2 (only assessed in male partner) | SCID-II (only assessed in male partner) | Female partner reported more IPV and more IPV-related injuries from their partners if they were in the ASPD or BPD (with or without ASPD) group versus no PD group. No significant differences between groups using men’s self-reports. | |

| Thomas et al. (2013) | N = 274 Alcohol or drug user (AOD) batterers M age = 37.28 N = 524 non-AOD batterers M age = 34.88 |

Cross-sectional; legal–jailed for IPV; data collected as part of intake interviews | CTS-2 (physical abuse subscale); | BPO scale | AOD batterers higher in BPO than non-AOD batterers | |

| Male and female samples–both male and female perpetration and male and female victimization (n = 1) | ||||||

| Walsh, Swogger, O’Connor, Schonbrun, Shea. & Stuart (2010) | N = 567 IPV group = 138 women. 93 men non-IPV group = 111 women, 225 men. M age = 29.8 (SD = 6.16) White 69.8%, Af Amer 28%. Hispanic 2% |

Legal and clinical–MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study (Monahan et al, 2001). Civil psychiatric patients | Patient self-report, collateral informants, review of police/hospital records | SCID | Female borderline /dysphoric (B/D) group distinguished by high levels of victimization. Female B/D victim group also had and highest levels of perpetration. Male B/D distinguished by high levels of antisociality. | |

| Couples/dyad samples–perpetration and victimization (n =6) | ||||||

| Babcock et al. (2008) | N = 110 couples M age = 32 Caucasian 33%, Af Amer 40%, Hispanic 19%. others 8% |

Cross-sectional: community | CTS-2 | MCMI-III | B/D men made the fewer facial affect recognition errors than generally violent/antisocial men. | |

| Costa and Babcock (2008) | N = 184 couples IPV = 130, distressed/nonviolent = 27, satisfied/nonviolent = 21 Men’s M age = 31 |

Cross-sectional: community | CTS-2 | MCMI borderline subscale | Intimate partner-abusive men scored higher than satisfied/non-violent men on borderline features. Personality features (rather than IPV and relationship dissatisfaction) accounted for differences in IPV men’s anger-related cognitive | |

| Gondolffi* White (2001) | N = 584 IPV perpetrators and their female partners Age range 18–25 = 24%. 26–35 = 47%, 36–65 = 30% White 49% |

Longitudinal (intake. 3-month follow-ups for 15 months): legal-IPV intervention programs | CTS physical aggression subscale at 3-month intervals (completed by female partners) verified against men’s reports and police records | MCMI-III | Reassault of partners associated with BPD-75% of reassaulters on borderline-avoidant continuum. | |

| Marshall and Holtzwoith-Munroe (2010) | N = 88 couples M age = 37.1 (SD = 9.4) for husbands M age = 343 (SD = 8.6) for wives |

Cross-sectional; lab study community sample | CTS-2 | Borderline, dysphoric (B/D) composite score–Beck Depression Inventory. Fear of Abandonment Subscale of the MCMI-II. Relationship Scales Questionnaire | B/D characteristics positively associated with IPV. Relation between B/D and IPV mediated by men’s lower skill at detecting happiness in their spouse | |

| Ross and Babcock (2009) | N = 124 couples M age = 32 years for men M age = 30 for women Caucasian 24% |

Cross-sectional: community–“couples experiencing conflict” | CTS-2 (only assessed in male partner) | SCID-II (only assessed in male partner) | Female partner reported more IPV and more IPV-related injuries from their partners if partner was in ASPD or BPD group versus no PD group. No significant differences between groups using men’s self-reports. | |

| Maneta et al.(2013) | N = 109 couples Men M age = 33.2 (SD = 8.8) Women M age = 31.7 (SD = 8.5) |

Cross-sectional; community | CTS-2–physical aggression subscale | Inventory of Personality Organization (IPO; Lenzenweger et al., 2001) | Male BPD traits were positively associated with both perpetration and victimization; female BPD traits were only positively associated with victimization. | |

| South et al. (2008) | N = 82 married couples Husbands M age = 33.6 (SD = 9.55) White 92% Wives M age = 32 (SD = 8.60) White 84% |

Cross-sectional: community | CTS: produced a composite of self-report and partner reported behavior–verbal aggression and physical violence | Multisource assessment of personality pathology (both self-report and informant report by spouse) | Higher IPV levels (as reported by spouse) linked to more verbal aggression and physical violence. More PD symptoms in partner linked to more partner perpetration. | |

3.1. Study designs and recruitment sites

The majority of studies (n = 24) were cross-sectional, with three of these having a lab or experimental component. Five studies were longitudinal in nature, with two of these drawing from the same larger study. These five studies followed participants who were involved in treatment for psychiatric or IPV issues. Only nine studies used control groups, with all but one being a non-IPV control group (the remainder being a non-BPD control group). Further, the studies cover a wide range of recruitment sites and sample, including—legal samples (n = 11), community samples (n = 8), clinical samples (n = 4), college samples (n = 2), and mixed samples (n = 4).

3.2. Operationalization and measurement of BPD and related constructs

Three distinct operational definitions of BPD and related constructs are present in the literature and included in this review: DSM-IV-TR BPD diagnostic criteria (i.e., symptoms; APA, 2000) borderline personality organization (BPO) (Oldham et al., 1985), and borderline/dysphoric typology (B/D). Furthermore, the BPD and related constructs were assessed using structured clinical interviews, self-report questionnaires, Q sort, content analysis, and clinician-ratings.

3.2.1. DSM-IV-TR BPD symptoms

Across all studies, self-report measures were by far the most common assessment tools. Fewer studies (n = 5) used a structured clinical interview to assess DSM-IV-TR BPD criteria. The Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory (MCMI-III; Millon, 1994) and Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire were the most commonly used measures to assess DSM-IV-TR BPD criteria to classify DSM-IV-TR BPD. Additional measures utilized included—a researcher-developed Axis II checklist that was completed by clinicians (Fowler & Westen, 2011), as well as a composite using the Beck Depression Inventory, the Fear of Abandonment Subscale of the MCMI, and the Relationship Scales Questionnaire (Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994).

3.2.2. Borderline personality organization

In addition, several studies assessed for borderline personality organization (BPO), which is characterized by three dimensions—identify diffusion, primitive defenses, and reality testing (Conrad & Morrow, 2000). These studies used one of two self-report instruments—the Self-Report Instrument for borderline personality organization (BPO; Oldham et al., 1985) or Inventory of Personality Organization (IPO; Lenzenweger, Clarkin, Kernberg, & Foelsch, 2001). Both instruments are self-report scales that assess the three dimensions. The construct of BPO is distinct from DSM-IV-TR conceptualizations (as well as from DSM-5 criteria with the exception of identity diffusion) of BPD in that it describes not only those with a BPD diagnosis, but also individuals with other personality disorders with similar psychological characteristics. These measures were originally designed to differentiate between individuals with BPO and individuals with psychotic and neurotic personality profiles (Oldham et al., 1985). Thus, caution must be taken when comparing these results to those of studies using DSM-IV-TR based measures of borderline personality pathology.

3.2.3. Borderline/dysphoric subtype

Four studies conducted typological analysis to assign participants to the various subtypes of IPV perpetrators utilizing Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart’s typological framework (1994)—generally violent/antisocial (AS), borderline/dysphoric (B/D), and family only/low-psychopathology (FO). Relevant to our review, perpetrators in the B/D subtype are generally characterized by both borderline features and affective disturbance, although each study used distinct measures and methods to assign subtypes: Walsh and colleagues utilized mixture modeling to assign male and female psychiatric patients to the subtypes, and found that those classified in the B/D subtype were characterized by high levels of neuroticism, BPD symptoms, and depressive symptoms. Huss and Ralston (2008) utilized three MCMI-III scales (depression, borderline, antisocial), as well as the physical violence subscales of the CTS-O and CTS-P; allowing them to examine specific personality characteristics, as well as violence towards others. Marshall and Holtzworth-Munroe (2010) constructed a dimensional B/D variable utilizing a composite score of the Beck Depression Inventory 2nd Edition (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996); the Fear of Abandonment Subscale of the MCMI-II; the Relationship Scales Questionnaire; and the CTS-2. Finally, Dixon, Hamilton-Giachritsis, and Browne (2008) used Multidimensional Scaling & Smallest Space Analysis (SSA) to characterize offenders by severity of violence and psychopathology (as determined by review of legal records across 20 variables) which were then correlated to Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart’s subtypes. Their findings indicated that the subgroup characterized by low to moderate criminal tendencies and high psychopathology were parallel to the B/D subtype.

3.2.4. Summary

As noted above, our review identified three distinct conceptualizations of borderline personality pathology in the literature on risk factors for IPV: DSM-IV-TR BPD symptoms, BPO, and B/D batterer subtype. However, even across studies with fairly similar conceptualizations of borderline personality pathology, we found a wide range of measures and analytic strategies that were used. One similarity across studies is that the vast majority relied upon respondent-completed measures of borderline personality pathology. Although not necessarily a limitation of any particular study, given that many of the studies we reviewed were not designed to assess the association between BPD and IPV, for our current purpose, there are difficulties with the use of self-report instruments to assess personality disorders. These include limited accuracy, confounding effects of mood state during assessment, and dichotomized responses. Despite the multitude of operational definitions and assessment methods used in the literature, as outlined below, BPD diagnostic criteria, BPO, and B/D were mostly linked with IPV perpetration.

3.3. Severity of IPV as a function of BPD

In terms of IPV severity, across studies reviewed, individuals meeting diagnostic criteria for BPD were more likely to commit seriously violent and aggressive acts of IPV perpetration (Lawson, Brossart, & Shefferman, 2010; Newhill, Eack, & Mulvey, 2009; Ross & Babcock, 2009). South, Turkheimer, and Oltmanns (2008) found that, in heterosexual couples, high verbal aggression was more likely to be perpetrated by a partner with BPD and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) when compared to other personality disorders. Whisman and Schonbrun (2009) suggested that BPD symptoms were associated with both minor and severe physical violence; however, Mauricio and Lopez (2009) found that BPD in a community sample of men predicted membership in only the most severe class of IPV perpetration, with each point increase on BPD scores increasing the odds of engaging in the most severe IPV. In addition, there is some evidence that links borderline personality pathology and spousal homicide. In a study of men incarcerated for spousal homicide, that one-third of men displayed B/D characteristics (Dixon et al., 2008).

3.4. Mechanisms of IPV in the context of BPD

3.4.1. Emotion perception

Drawing from conceptualizations of BPD that highlight the role of sensitivity to emotional stimuli (Linehan, 1993) and from social information processing models of IPV (Holtzworth-Munroe, 2000), two studies tested the role of biased perception of emotional displays in B/D husbands’ IPV perpetration. Babcock, Green, and Webb (2008) found that B/D IPV perpetrators were more accurate in identifying standardized facial affect displays than all other subgroups of husbands (i.e., non-violent, family-only violent, and generally violent/antisocial). In a more direct examination of emotion perception as a mechanism of borderline features and IPV, Marshall and Holtzworth-Munroe (2010), showed that husbands’ diminished sensitivity to their wives’ (but not unfamiliar men and women’s) facial expressions of happiness partially mediated the association between their B/D characteristics and IPV perpetration. Importantly, these findings do not allow for conclusions about how men classified as B/D might differ from those diagnosed with BPD or controls. However, it is noteworthy that the findings are generally consistent with research suggesting that individuals with BPD appraise ambiguous facial expressions in an overly negative manner (Dyck et al., 2008; Meyer, Pilkonis, & Beevers, 2004).

These studies suggest that biased processing of emotional expressions may serve as a mechanism of the association between BPD and IPV, but the nature of the bias is unclear (i.e., more or less accurate perception) and may differ as a function of the relationship type (i.e., intimate partners versus strangers). It may be that, due to the salience of close relationships in BPD (Gunderson, 2007), emotional processing biases associated with BPD are more pronounced with respect to intimate partners. For example, appraising intimate partners’ ambiguous emotional expressions in an overly negative manner could increase risk for IPV via increases in negative affect and arousal and activation of fears or abandonment or rejection. In fact, emotion dysregulation (Newhill, Eack, & Mulvey, 2012) and interpersonal dysfunction (i.e., interpersonal sensitivity, interpersonal aggression, need for social approval, and lack of sociability; Stepp, Smith, Morse, Hallquist, & Pilkonis, 2012) mediated the association between BPD and general aggressive behavior in longitudinal st.

3.4.2. Attachment

Also consistent with Dutton’s theory (1995), Mauricio and Lopez (2009) demonstrated that men classified as moderately or severely violent exhibited anxious adult attachment in addition to elevated borderline personality characteristics. Further, Dutton, Saunders, Starzomski, and Bartholomew (1994) posited that insecurely attached individuals with high BPO may be apt to perceive partners as unavailable, cueing abandonment anxiety to which they respond with hostile, overt, expressions of anger (Dutton et al., 1994). Studies guided by this conceptualization have tested whether BPD served as a mechanism in the association between insecure attachment and IPV, and shown mixed results. For example, in court-mandated male batterers, BPD symptoms served as a mediator of the relationship between anxious attachment and physical IPV perpetration (Mauricio, Tein, & Lopez, 2007). Later work with a similar sample indicated that BPD, as well as anxious and avoidant attachment (in adulthood), predicted the most severe IPV perpetration; anxious attachment predicted moderate violence; and neither BPD nor attachment predicted low level violence (Mauricio & Lopez, 2009). In a sample of men on probation for IPV, however, BPD features failed to mediate the association between anxious attachment and IPV (Lawson & Brossart, 2013). These authors also tested the explanatory role of hostile-dominant interpersonal problems (HDIP; characterized by vindictive, domineering, and intrusive behavior), which fully mediated the association. In comparing findings to those of udies. Mauricio et al. (2007), Lawson and Brossart posited that HDIP held more explanatory power than borderline (or antisocial) features when considering the roles of all three variables in predicting IPV. However, the bivariate associations between BPD features and HDIP was large (r = .51) and between BPD features and violence severity was moderate (r = .33), reinforcing the idea that BPD, dysfunctional interpersonal styles, and IPV are closely related.

Relatedly, one experimental study suggested that exposure to abandonment cues may serve as a mechanism of IPV for individuals with borderline personality pathology. Conrad and Morrow (2000) found that male college students high in BPO who watched a video depicting a media portrayal of childhood abandonment reported more willingness to use verbal aggression in a conflict with an intimate partner than did low-BPO men and high-BPO men exposed to a neutral video. However, this effect did not appear to be unique to abandonment cues, as high-BPO men who viewed a media portrayal of general violence were also more likely than high-BPO men in the control condition to report willingness to use verbal aggression.

3.4.3. Alcohol and other substance use

Substance use has been shown to serve as a mechanism of IPV with respect to other forms of psychopathology (e.g., PTSD; Savarese, Suvak, King, & King, 2001). In a cross-sectional study of male IPV perpetrators, those who used alcohol or drugs were more likely to (a) have high BPO, and (b) perpetrate more severe violence than those who did not use alcohol or drugs (Thomas, Bennett, & Stoops, 2013), indicating a potential interactional risk of substance use and BPO on IPV severity. However, no study has directly tested the role of substance use in the association between BPD and IPV perpetration.

3.4.4. Impulsivity

Another potential mechanism for BPD-related IPV that was not directly examined in any of the studies included in this review and could serve as a target for future research is impulsivity. BPD is characterized by impulsivity (i.e., an inability to regulate certain behaviors), which has in turn been linked to IPV (Cohen et al., 2003; Hamberger & Hastings, 1991). In fact, impulsivity may partly explain the overlap in the borderline/dysphoric and generally violent/antisocial subtypes (Holtzworth-Munroe, Meehan, Herron, Rehman, & Stuart, 2003) and underlie the more severe violence perpetrated by individuals presenting with both ASPD and BPD relative to individuals with only BPD (Newhill et al., 2009). To our knowledge, however, no study has directly tested whether impulsivity serves as a mechanism of BPD-related IPV perpetration.

3.4.5. Summary

The research that we reviewed identified a variety of potential mechanistic factors that may interplay in important ways to promote IPV among individuals with borderline pathology, including emotional perception biases, emotion dysregulation, dysfunctional interpersonal styles, attachment, substance use and impulsivity. Other work suggests that BPD itself may serve as a mechanism of IPV related to, for example, child maltreatment (e.g., Hughes, Stuart, Gordon, & Moore, 2007). Ultimately, the development and examination of more complex models detailing the developmental and static risk factors for BPD-related IPV is needed.

3.5. Sex differences in BPD and IPV perpetration

3.5.1. Women, BPD, and IPV

Despite fewer studies of the link between BPD and IPV in women, the existing literature generally supports an association between borderline personality pathology and IPV perpetration in women. Borderline personality organization (BPO) in female IPV perpetrators was significantly correlated with frequency of both psychological and physical aggression (Clift & Dutton, 2011), and this group was more likely to perpetrate IPV than experience IPV victimization. Similarly, in a sample of female IPV perpetrators involved in the legal system, borderline personality features were significantly associated with frequency of physical aggression towards partners, but not by partners (Hughes et al., 2007). Two studies indicated that female IPV perpetrators—both heterosexual and lesbian—were higher on BPD features than non-IPV comparison groups (Fortunata & Kohn, 2003; Goldenson, Geffner, Foster, & Clipson, 2007). This finding seems to hold true with male samples, as well, in that male IPV perpetrators were higher in BPD features than non-violent men (Costa & Babcock, 2008; Edwards, Scott, Yarvis, Paizis, & Panizzon, 2003; Porcerelli, Cogan, & Hibbard, 2004).

3.5.2. Sex comparisons of BPD and IPV

Although there is an established association between borderline personality pathology and IPV for both men and women, studies that directly compare male and female perpetrators suggest some potential differences in the BPD–IPV perpetration association between men and women. However, findings across studies are quite mixed with some suggesting a stronger association for women and others suggesting a stronger association for men. In a nationally representative sample (Ross, 2011), for both men and women, emotional dysregulation was strongly related to both borderline traits and defensive violence, whereas retaliatory violence was associated with BPD in men, but not in women (rather, this type of violence in women was associated with situational contexts). Walsh and colleagues (2010) found that female perpetrators with B/D traits were most likely to be characterized by victimization, compared to their male B/D counterparts who were more likely to be characterized by additional antisocial traits. Maneta and colleagues (2013) found that in 109 heterosexual couples, men with higher levels of BPD were both more frequent perpetrators of IPV and greater victims of IPV from their partners. In women, no association was found between borderline level and IPV perpetration, but a positive relation was found with their IPV victimization. In contrast, Weinstein, Gleasons, and Oltmanns (2012), suggested that BPD symptoms more strongly relate to IPV perpetration in women compared to men.

3.5.3. Sex asymmetry in the research on IPV and BPD

Given the limited research and mixed findings in the literature, no clear sex-related IPV–BPD association could be gleaned from our review. Future studies should continue examining the role of sex in the relation between BPD and IPV perpetration in order to elucidate whether this association differs between men and women and, if so, the specific nature of any differences. Within this call for additional work, the current findings point to a shortage of studies in particular examining female IPV perpetrators (n = 13 studies versus n = 24 in males). This is consistent with the broader literature on IPV, which is characterized by far more studies on male-than female-perpetrated IPV. Greater research on female-perpetrated IPV is needed given that the estimated prevalence of past year IPV victimization in males in the U.S. is certainly not negligible and comparable to women (5.6%), rate of perpetration in women is not much lower than it is in males (4% versus 7%), and approximately 3.1% of men and women report being both victims and perpetrators within their relationships (Afifi et al., 2012; Okuda et al., 2011). Although women are diagnosed more than men (Torgersen et al., 2001), it appears that the clinical profiles of men and women with BPD are similar (Johnson et al., 2003); thus it is important to conduct additional research on the role of BPD and BPD traits in the development of IPV perpetration in both women and men.

3.5.4. Summary

The research examining the role of sex in the association between BPD and IPV perpetration is limited and mixed. Moving forward, the most accurate method of studying these associations might be in dyadic form within the couple such that contextual information related to the violence as well as the relationship dynamic can be thoroughly captured. Finally, the vast majority of studies reviewed studied IPV within heterosexual couples. More research is required with regard to the relationship between IPV and BPD within LGBT relationships as sexual orientation might impact the role of sex is this relation.

3.5. ASPD and BPD

Several studies attempted to delineate between BPD and antisocial traits as they relate to IPV perpetration. For example, BPD was more prevalent than ASPD (27% vs. 7%) in a group of women in treatment for IPV perpetration (Stuart, Moore, Gordon, Ramsey, & Kahler, 2006). Further, there are some mixed findings regarding BPD and ASPD as they relate to BPD in male samples. Huss and Ralston (2008) suggested that a B/D subgroup of men in court-mandated treatment for IPV perpetration was generally less violent than a violent/antisocial subgroup. However, BPD remained a significant predictor of IPV perpetration after controlling for general criminality and SUDs, but not after also controlling for ASPD, indicating a shared variance between BPD and ASPD (Newhill et al., 2009). Overall, while these studies suggest that BPD is a risk factor for IPV perpetration, BPD itself may not be a unique risk factor for IPV perpetration when comorbid ASPD is present.

4. Conclusions

4.1. Summary across studies

In summarizing the reviewed studies, there appears to be robust evidence for an association between BPD and IPV perpetration. Specifically, individuals with BPD symptoms seem to be a risk for perpetrating more severe and frequent IPV. Further, while few studies have included direct measurement and examination of potential mechanisms for this association, attachment and facial affect processing appear to be two potential mechanisms of IPV perpetration in individuals with BPD. In addition, we examined whether there is any evidence to suggest sex differences with respect to the BPD–IPV perpetration association. Here we observed far more studies focused on men as perpetrators in the BPD–IPV literature, despite BPD being more frequently diagnosed in women. There was no clear sex difference in the magnitude or direction of the BPD–IPV perpetration association, but given the relatively limited research on women as IPV perpetrators and the even more limited research directly comparing men and women with borderline personality pathology who engage in IPV, additional research is needed.

4.2. General limitations across studies

Perhaps the clearest limitations—and the largest challenge—we observed while attempting to draw conclusions across studies was heterogeneity in researchers’ conceptualizations of BPD. We observed the use of trait (i.e., BPO), typology (i.e., B/D), and pathology (i.e., BPD) operationalizations across studies. While some researchers correlated BPO or B/D with BPD (e.g., Edwards et al., 2003), none attempted to examine all three constructs within the same sample to determine how the definition and assessment of each may impact study findings and interpretations. In addition, several of the studies looked at BPD using a continuous, dimensional perspective (e.g. symptom-level) rather than diagnostic approach. It should be noted that there is a qualitative difference between receiving a diagnosis of BPD and endorsing several BPD symptoms on a self-report questionnaire. Individuals meeting full criteria for BPD would likely present with more severe symptomatology, possibly enhancing the likelihood of IPV perpetration. Further, while three of the four BPO-related studies used the same assessment measure, the remainder of reviewed studies used a wide variety of assessment measures, including brief and extensive personality self-report measures, structured clinical interviews, and investigator-developed checklists. These differences in how constructs were defined and assessed make it difficult to draw clear conclusions across the literature about the BPD–IPV relation due, at least in part, to these differences in measurement—for example, while this association did not appear to differ as a function of definition or measurement type, studies that utilized all self-report measures might be limited by shared method variance, while studies using structured interviews only may be more limited by social desirability (e.g., Clements, Schumacher, Coffey, & Saladin, 2011).

IPV was measured in a more consistent manner across studies, with the majority of studies using some form or variation of the CTS. However, this scale has at least two limitations with regard to the questions of interest in this review—(1) retrospective memory biases of frequency of behaviors over a specified time period and (2) lack of context regarding course and interactional processes of IPV behaviors. Further, there are inconsistencies across studies in which a partner provided the data regarding IPV, regardless of measure used. Specifically, some studies had female partners report on male partners’ IPV behaviors, while others had only the male perpetrators report. While there are certain logistical concerns that may prevent access to victims’ responses (e.g., the relationship is not ongoing and the victim is no longer involved with a perpetrator) and may bias samples that recruit couples rather than individuals, assessments that include reports from both victims and perpetrators—as was seen with several studies in this review—would be most useful by allowing researchers to determine and account for any discrepancies in partners’ perceptions of IPV that is reported in existing literature. For example, several studies demonstrated low-tomoderate concordance between partners’ reports of IPV (e.g., Archer, 2001; Freeman, Schumacher, & Coffey, 2015; Caetano, Field, Remisetty-Mikler, & Lipsky, 2009).

An additional methodological issue seen across the majority of studies was lack of control groups. Few studies included control groups—whether non-BPD or non-IPV samples—thus limiting the conclusions that can be drawn regarding the unique relation between BPD and IPV. Further, some studies did not measure or control for diagnostic comorbidities, which, again, limits the conclusions that can be drawn about the unique relation between BPD and IPV; for example, these studies could not account for the possible contributions of psychopathologies that are highly comorbid with BPD (e.g., PTSD, substance use; Afifi et al., 2012; Campbell, 2002; Coker et al., 2002).

4.3. Future research directions

Moving forward, we recommend that researchers can make greater contributions to our understanding of the BPD–IPV association by focusing on measurement of BPD and IPV. For example, future IPV–BPD researchers may wish to develop and/or utilize measures that capture the dyadic interactional processes inherent to IPV, which are especially important to examine in the context of BPD given the variety of forms of interpersonal dysfunction observed in BPD. Further, it will be important to consider the most useful definition and assessment tools to capture the construct of BPD. We observed much variation in BPD measurement across studies, and the literature would benefit from future work on determining the most valid and reliable measurement instruments, especially with recent diagnostic changes in the DSM-V. Relatedly, differentiation between a BPD diagnosis and the dimensional assessment of BPD symptoms appears to be particularly important for future research endeavors. In cases in which BPO and B/D are the specific constructs of interest, it will be important for authors to distinguish these constructs from BPD and discuss benefits and limitations of drawing conclusions using these constructs.

Further, we observed some gaps in the literature, per this review, that would be worthy of additional study. Researchers have most typically conceptualized men as perpetrators and women as victims, and measured IPV and BPD accordingly. Additional research examining samples of male and female perpetrators and victims will provide a more nuanced view of how BPD and IPV operate in these samples. Moreover, additional research is needed in the BPD–IPV relation in same-sex couples, given the high prevalence of IPV in these couples (e.g., Marshall & Holtzworth-Munroe, 2010). In addition, examining dyadic processes (especially where both members of dyad may have BPD) is particularly needed in the current literature in order to better understand the dynamic and reciprocal role BPD may play in a relationship. Research on the mechanisms of IPV in individuals with BPD is also needed, particularly mechanisms related to BPD symptoms such as emotional dysregulation and relationship instability as these make up two potential components of IPV. Further, investigation into the function and course of IPV over time for individuals with BPD may be particularly helpful in guiding clinical intervention. For example, examination of whether IPV is a first response to emotional dysregulation within the relationship context, or whether it occurs after other, ineffective attempts to regulate affect and emotions (e.g., self-harm, alcohol use) may be worthy of study, in order to determine the most effective point of intervention.

4.4. Clinical implications

Several clinical implications emerged from this review. First, it is important to recognize the impact of treatment setting on assessment of the BPD construct. BPO and B/D—that is, trait-based conceptualizations of BPD—appear to be more present within legally involved samples, such as individuals court-mandated to IPV treatment, whereas BPD—that is, psychiatric diagnosis—is more commonly assessed within clinical samples. Similarly, clinicians and providers within each setting may focus on differing aspects of functioning due to the nature of the treatment objectives within each setting—within court-mandated treatment programs and other legally-influenced contexts, IPV is likely to be the primary target of intervention; whereas we might expect a focus on BPD symptoms in a clinical setting. It is important for providers within the clinical setting to be aware of the relation between IPV and BPD and to extend their assessment of IPV to include not only victimization but perpetration as well, along with appropriate intervention. While further research is needed on (1) mechanisms of the BPD–IPV relation and (2) effective interventions, the literature is suggestive that BPD contributes to higher dropout of IPV treatment (e.g., Hamberger, Lohr, & Gottlieb, 2000)—thus targeting BPD may be effective in improving treatment retention for IPV perpetrators with legal-involvement. However, additional research on this issue is necessary.

Contributor Information

Michelle A. Jackson, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, Jackson, MS, USA and Methodist Rehabilitation Center, Department of Neuropsychology, Jackson, MS, USA

Lauren M. Sippel, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, Jackson, MS, USA, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, National Center for PTSD, West Haven, CT, USA and Yale University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, New Haven, CT, USA

Natalie Mota, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, Jackson, MS, USA, and Yale University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, New Haven, CT, USA.

Diana Whalen, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, Jackson, MS, USA and Washington University, Department of Psychiatry, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Julie A. Schumacher, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, Jackson, MS, USA

References

- Afifi TO, Henriksen CA, Asmundson GJG, Sareen J. Victimization and perpetration of intimate partner violence and substance use disorders in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2012;200:684–691. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182613f64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afifi TO, MacMillan H, Cox BJ, Asmundson GG, Stein MB, Sareen J. Mental health correlates of intimate partner violence in marital relationships in a nationally representative sample of males and females. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24(8):1398–1417. doi: 10.1177/0886260508322192. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260508322192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A metaanalytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;126(5):651. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Green CE, Webb SA. Decoding deficits of different types of batterers during presentation of facial affect slides. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23:295–302. [Google Scholar]

- Bagge CL, Nickell A, Stepp SD, Durrett C, Jackson K, Trull TJ. Borderline personality disorder features predict negative outcomes 2 years later. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(2):279–288. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagge CL, Stepp SD, Trull TJ. Borderline personality disorder features and utilization of treatment over two years. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19(4):420–439. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.4.420. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2005.19.4.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory-Second edition manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, Sanislow CA, Dyck IR, McGlashan TH, Shea MT, et al. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):295–302. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Field C, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Lipsky S. Agreement on reporting of physical, psychological, and sexual violence among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24(8):1318–1337. doi: 10.1177/0886260508322181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt J, Kim HK. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3(2):1–194. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Costs of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding intimate partner violence: Fact sheet. Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2012. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv_factsheet2012-a.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- Clements K, Schumacher JA, Coffey SF, Saladin ME. Detecting ongoing intimate partner victimization in the lives of trauma survivors with substance use disorders: The need for supplemental assessment. Partner Abuse. 2011;2:46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Clift RW, Dutton DG. The abusive personality in women in dating relationships. Partner Abuse. 2011;2(2):166–188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/1946-6560.2.2.166. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RA, Brumm V, Zawacki TM, Paul R, Sweet LH, Rosenbaum A. Impulsivity and verbal deficits associated with domestic violence. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2003;9:760–770. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703950090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coid J, Yang M, Bebbington P, Moran P, Brugha T, Jenkins R, Ullrich S. Borderline personality disorder: Health service use and social functioning among a national household population. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39(10):1721–1731. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2002;23:260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad S, Morrow R. Borderline personality organization, dissociation, and willingness to use force in intimate relationships. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2000:137–48. [Google Scholar]

- Costa DM, Babcock JC. Articulated thoughts of intimate partner abusive men during anger arousal: Correlates with personality disorder features. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23(6):395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Browne K. Classifying partner femicide. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:74–93. doi: 10.1177/0886260507307652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton DG. The domestic assault of women: Psychological and criminal justice perspectives. Canada: UBC Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton DG, Saunders K, Starzomski A, Bartholomew K. Intimacy, anger, and insecure attachment as precursors of abuse in intimate relationships. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1994;24:1367–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Dyck M, Habel U, Slodczyk J, Schlummer J, Backes V, Schneider F, Reske M. Negative bias in fast emotion discrimination in borderline personality disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2008;39:855–864. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards DW, Scott CL, Yarvis RM, Paizis CL, Panizzon MS. Impulsiveness, impulsive aggression, personality disorder, and spousal violence. Violence and Victims. 2003;18:3–14. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Johnson JG. Development of personality disorder symptoms and the risk for partner violence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:474–483. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.474. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortunata B, Kohn CS. Demographic, psychosocial, and personality characteristics of lesbian batterers. Violence & Victims. 2003;18(5):557–568. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.5.557. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/vivi.2003.18.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler KA, Westen D. Subtyping male perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(4):607–639. doi: 10.1177/0886260510365853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman AJ, Schumacher JA, Coffey SF. Social desirability and partner agreement of men’s reporting of intimate partner violence in substance abuse treatment settings. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015;30(4):565–579. doi: 10.1177/0886260514535263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260514535263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenson J, Geffner R, Foster SL, Clipson CR. Female domestic violence offenders: Their attachment security, trauma symptoms, and personality organization. Violence & Victims. 2007;22(5):532–545. doi: 10.1891/088667007782312186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondolf E, White R. Batterer program participants who repeatedly reassault: Psychopathic tendencies and other disorders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16(3):61–380. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Kevan N, Archer J. Physical aggression and control in heterosexual relationships: The effects of sampling. Violence & Victims. 2003;18:181–196. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.2.181. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/vivi.2003.18.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, Ruan WJ. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):533–545. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin DW, Bartholomew K. Models of the self and other: Fundamental dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:430–445. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson JG. Disturbed relationships as a phenotype for borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1637–1640. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson JG, Lyons-Ruth K. BPD’s interpersonal hypersensitivity phenotype: A gene–environment-developmental model. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2008;22(1):22–41. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.1.22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2008.22.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger LK, Guse CE. Men’s and women’s use of intimate partner violence in clinical samples. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:1301. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/107780102762478028. [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger LK, Hastings JE. Personality correlates of men who batter and non-violent men: Some continuities and discontinuities. Journal of Family Violence. 1991;6:131–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger L, Lohr JM, Gottlieb M. Predictors of treatment dropout from a spouse abuse abatement program. Behavior Modification. 2000;24(4):528–552. doi: 10.1177/0145445500244003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0145445500244003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J, Pilkonis P, Morse J, Feske U, Reynolds S, Hope H, Broyden N. Social domain dysfunction and disorganization in borderline personality disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(1):135–146. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001626. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707001626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm AL, Severinsson E. Struggling to recover by changing suicidal behaviour: Narratives from women with borderline personality disorder. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2011;20(3):165–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00713.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A. Social information processing skills deficits in martially violent men: Summary of a research program. In: Vincent JP, Jouriles EN, editors. Domestic violence: Guidelines for research-informed practice. London: Jessica Kingsley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe AM, Meehan JC, Herron K, Rehman U, Stuart GL. Do subtypes of maritally violent men continue to differ over time? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:728–740. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Stuart GL. Typologies of male batterers: Three subtypes and differences among them. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:476–497. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.476. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes FM, Stuart GL, Gordon KC, Moore TM. Predicting the use of aggressive conflict tactics in a sample of women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24:155–176. [Google Scholar]

- Huss MT, Ralston A. Do batterer subtypes actually matter? Treatment completion, treatment response, and recidivism across a batterer typology. Criminal Justice & Behavior. 2008;35(6):710–724. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0093854808316218. [Google Scholar]

- Hyler SE. Personality diagnostic questionnaire for DSM-IV (PDQ-4) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP. Gender and types of intimate partner violence: A response to an anti-feminist literature review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2011;16:289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Leone JM, Xu Y. Intimateterrorism andsituational coupleviolencein general surveys: Ex-spouses required. Violence Against Women. 2014;20:186. doi: 10.1177/1077801214521324. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077801214521324 (originally published online 6 February 2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Shea MT, Yen S, Battle CL, Zlotnick C, Sanislow CA, Zanarini MC. Gender differences in borderline personality disorder: Findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2003;44(4):284–292. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korzekwa MI, Dell PF, Links PS, Thabane L, Webb SP. Estimating the prevalence of borderline personality disorder in psychiatric outpatients using a two-phase procedure. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2008;49(4):380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson DM, Brossart DF. Interpersonal problems and personality features as mediators between attachment and intimate partner violence. Violence and Victims. 2013;28:414–428. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-12-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson DM, Brossart DF, Shefferman LW. Assessing gender role of partner-violent men using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2): Comparing abuser types. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2010;41(3):260–266. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0019589. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger MF, Clarkin JF, Kernberg OF, Foelsch PA. The Inventory of Personality Organization: Psychometric properties, factorial composition, and criterion relations with affect, aggressive dyscontrol, psychosis proneness, and self domains in a nonclinical sample. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13(4):577–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62(6):553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Loranger AW. International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE) Screening Questionnaire. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1999b. [Google Scholar]

- Maneta E, Cohen S, Schulz MS, Waldinger RJ. Two to tango: A dyadic analysis of links between borderline personality traits and intimate partner violence. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2013;27:233–243. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2013.27.2.233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2013.27.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall AD, Holtzworth-Munroe A. Recognition of wives’ emotional expressions: A mechanism in the relationship between psychopathology and intimate partner violence perpetration. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:21–30. doi: 10.1037/a0017952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauricio AM, Lopez FG. Alatent classification of male batterers. Violence & Victims. 2009;24:419–438. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.4.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauricio AM, Tein JY, Lopez FG. Borderline and antisocial personality scores as mediators between attachment and intimate partner violence. Violence and Victims. 2007;22:139–157. doi: 10.1891/088667007780477339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B, Pilkonis PA, Beevers CG. What’s in a (neutral) face? Personality disorders, attachment styles, and the appraisal of ambiguous social cues. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2004;18:320–326. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2004.18.4.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millon T. The Millon Inventories: Clinical and personality assessment. New York, NY: Guilford; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Newhill CE, Eack SM, Mulvey EP. Violent behavior in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2009;23:541–554. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.6.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhill CE, Eack S, Mulvey EP. A growth curve analysis of emotion dysregulation as a mediator for violence in individuals with and without borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2012;26(3):452–467. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2012.26.3.452. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2012.26.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda M, Olfson M, Hasin D, Grant BF, Lin KH, Blanco C. Mental health of victims of intimate partner violence: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62(8):959–962. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.8.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham J, Clarkin J, Appelbaum A, Carr A, Kernberg P, Lotterman A. Aselfreport instrument for borderline personality organization. In: McGlashan TH, editor. The borderline: Current empirical research. Washington: American Psychiatric Press; 1985. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pan HS, Neidig PH, O’Leary KD. Predicting mild and severe husbandto-wife physical aggression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994 Oct.62(5):975–981. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcerelli JH, Cogan R, Hibbard S. Personality characteristics of partner violent men: A Q-sort approach. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2004;18:151–162. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.2.151.32776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal MZ, Gratz KL, Kosson DS, Cheavens JS, Lejuez CW, Lynch TR. Borderline personality disorder and emotional responding: A review of the research literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(1):75–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.04.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JM. Personality and situational correlates of self-reported reasons for intimate partner violence among women versus men referred for batterers’ intervention. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2011;29(5):711–727. doi: 10.1002/bsl.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JM, Babcock JC. Proactive and reactive violence among intimate partner violent men diagnosed with antisocial and borderline personality disorder. Journal of Family Violence. 2009;24:607–617. [Google Scholar]

- Savarese VW, Suvak MK, King LA, King DW. Relationships among alcohol use, hyperarousal, and marital abuse and violence in Vietnam veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:717–732. doi: 10.1023/A:1013038021175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J, Caetano R, Clark CL. Rates of intimate partner violence in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(11):1702–1704. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.11.1702. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.88.11.1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Feldbau-Kohn S, Slep AMS, Heyman RE. Risk factors for male-to-female partner physical abuse. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2001;6:281–352. [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Pfohl B, Widiger TA, Livesley WJ, Siever LJ. The borderline diagnosis: I. Psychopathology, comorbidity and personality structure. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:936–950. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Pagano ME, Bender DS, Shea MT, Gunderson JG, Yen S, McGlashen TH. Stability of functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive–compulsive personality disorder over two years. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35(3):443–451. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400354x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloff PH, Lynch KG, Kelly TM. Childhood abuse as a risk factor for suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002;16(3):201–214. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.3.201.22542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South SC, Turkheimer E, Oltmanns TF. Personality disorder symptoms and marital functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(5):769–780. doi: 10.1037/a0013346. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0013346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepp D, Smith TD, Morse JQ, Hallquist MN, Pilkonis P. Prospective associations among borderline personality disorder symptoms, interpersonal problems, and aggressive behaviors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27:103–124. doi: 10.1177/0886260511416468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus Murray A. Measuring intra family conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979 Feb;41(1):75–88. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/351733. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Moore TM, Gordon K, Hellmuth JC, Ramsey SE, Kahler CW. Reasons for intimate partner violence perpetration among arrested women. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:609–621. doi: 10.1177/1077801206290173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077801206290173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MD, Bennett LW, Stoops C. The treatment needs of substance abusing batterers: A comparison of men who batter their female partners. Journal of Family Violence. 2013;28(2):121–129. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10896-012-9479-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM. The development of a measure of psychological maltreatment of women by their male partners. Violence and Victims. 1989;4(3):159–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V. The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:590–596. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Jahng S, Tomko RL, Wood PK, Sher KJ. Revised NESARC personality disorder diagnoses: Gender, prevalence, and comorbidity with substance dependence disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2010;24(4):412. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2010.24.4.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Useda JD, Conforti K, Doan BT. Borderline personality disorder features in nonclinical young adults: 2. Two-year outcome. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(2):307–314. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh Z, Swogger MT, O’Connor BP, Chatav Schonbrun Y, Shea MT, Stuart GL. Subtypes of partner violence perpetrators among male and female psychiatric patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010 Aug.119(3):563–574. doi: 10.1037/a0019858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein Y, Gleason ME, Oltmanns TF. Borderline but not antisocial personality disorder symptoms are related to self-reported partner aggression in late middle-age. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(3):692–698. doi: 10.1037/a0028994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westen D, Shedler J. Revising and assessing Axis II, Part 1: Developing a clinically and empirically valid assessment method. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999a;156:258–272. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westen D, Shedler J. Revising and assessing Axis II, Part 2: Toward an empirically based and clinically useful classification of personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999b;156:273–285. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Schonbrun YC. Social consequences of borderline personality disorder symptoms in a population-based survey: Marital distress, marital violence, and marital disruption. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2009;23(4):410–415. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.4.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Marino MF, Haynes MC, Gunderson JG. Violence in the lives of adult borderline patients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1999;187(2):65–71. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199902000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweig-Frank H, Paris J. Predictors of outcome in a 27-year follow-up of patients with borderline personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2002;43(2):103–107. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.30804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]