Abstract

In this paper we applied analytical theories for the two dimensional chain-forming fluid. Wertheims thermodynamic perturbation theory (TPT) and integral equation theory (IET) for associative liquids were used to study thermodynamical and structural properties of the chain-forming model. The model has polymerizing points at arbitrary position from center of the particles. Calculated analytical results were tested against corresponding results obtained by Monte Carlo computer simulations to check the accuracy of the theories. The theories are accurate for the different positions of patches of the model at all values of the temperature and density studied. The IET’s pair correlation functions of the model agree well with computer simulations. Both TPT and IET are in good agreement with the Monte Carlo values of the energy, chemical potential and ratios of free, once and twice bonded particles.

Keywords: Integral equation theory, association, thermodynamic perturbation theory, chain forming fluid

1. Introduction

Important part of the computational physics and chemistry is to develop analytical solution which require less computation time in comparison to computer simulations. Molecular dynamics and Monte Carlos simulations can take long time to yield one reliable single point on a phase diagram. Analytic theories like integral equations theory (IET) and thermodynamic perturbation theory (TPT) provide us with a fast and easy-to-implement method of calculating pair distribution function and thermodynamic properties for various models [1] and allows a rather quick calculation of properties along the isotherms or isochores. But unfortunately both, IET and TPT, are in principle approximations and as such can provide wrong predictions. Caution must therefore be exercised to use IET with appropriate closures in regions where their use is justified, meaning that we must first test correctness of both theories in order to make predictions of model.

Wertheim developed a theory that is used for fluids which is composed of molecules that associate into dimers and higher clusters due to the presence of highly directional attractive forces [2, 3]. The theory is named Wertheim’s associating theory. It was demonstrated by application that theory can provide good results. It was successfully applied to a number of different three-dimensional systems, including water and aqueous solutions (see, for example [4, 5, 6] and references therein) and two-dimensional fluid systems like Mercedes-Benz model of water[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. In this work, we applied two variants of the Wertheim’s associating theory for fluids: the thermodynamic perturbation theory (TPT) [2, 3, 15, 16], and the integral equation theory (IET) [2, 17, 18]. Each has some specific advantages. TPT can easily calculate thermodynamics of system without knowing the structure while IET has on the other hand advantage over TPT because it provides both the structural (in forms of pair correlation functions) and thermodynamic properties for studied model.

Important associative fluid is water which has various anomalous properties in comparison to simpler (argon like) fluids. The most known anomalous properties of pure water are: density of ice is lower then density of liquid water, a temperature of maximum density in the liquid phase, a minimum in the isothermal compressibility, and large heat capacity. The anomalies are related to the ability of water molecules to form tetrahedrally coordinated hydrogen bonds which can be described as associative interactions. Scientists developed many theoretical and computational models to provide insight and explain these properties. One of the simplest models of water is the MB model which was originally developed by Ben–Naim in 1971 [19]. Recently, it has been developed further to 3D by Bizjak et al.[20, 21] and Dias et al.[22, 23]. 2D MB model captures two aspects of water physics in a simple way: Lennard-Jones interactions for long-ranged attractions and short-ranged repulsions, and an orientation dependent interaction to mimic hydrogen bonding effects. Particles of water are modeled as two–dimensional Lennard–Jones disks, with three hydrogen–bonding arms, arranged as in the Mercedes– Benz (MB) logo. A Monte Carlo simulations have shown that it predicts qualitatively the density anomaly, the minimum in the isothermal compressibility as a function of temperature, the large heat capacity, and the experimental trends for the thermodynamic properties of solvation of nonpolar solutes [7]. Theoretical treatments of MB model were in agreement with simulation for high temperatures [8], but at low temperatures the agreement was not that good. There are multiple reasons possible for this. One possibility is omitting ring structures in theoretical treatment, another possibility is closure. In this study we investigate the properties fluid described by an associative potential with soft core. Potential is similar to the one used in Mercedes-Benz model of water [7, 19], but we kept only two arms so that molecules can only form linear chains. This work is continuation of study where we developed similar model which only allowed formation of dimers [14]. For our two arm model we tested if the in TPT and IET can perform well and from this conclude what might be problem in case of MB model. Meaning if disagreement is related to number of associative arms and their positions. Both theories for two arms have approximation of orientationally averaging of associating potential as in case of one arm. In one arm case there is no correlation between arms within the molecule while in two arms case there is. Orientationally averaging mean that in theory arms are no longer fixed, but can take random angle between them. Beside testing the affect of number of arms on correctness of theories studied this model can be used as a model for chemical reaction of polymerizing which takes place due to site-site associative interactions. Model can also be used to predict properties of patch colloids with soft core and two attraction point. In case of strong polymerization the model can be also used to describe properties of linear soft chains.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we present the model, continue with description of the TPT and IET specialized for the model at hand in Section 3 and in Section 4, the computer simulations details are given. In section 5 we presented and discussed results of both theories in comparison with Monte Carlo simulation data for potential like in MB potential, but with only two active arms. The paper is finished with concluding remarks in Section 6.

2. The model

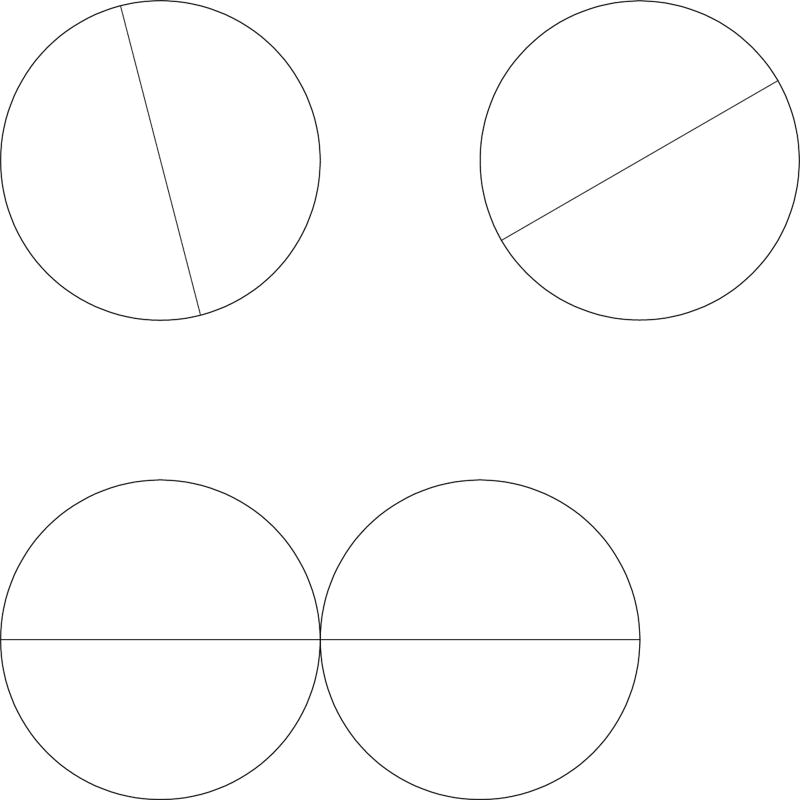

Molecules of chain-forming fluid are modeled as two–dimensional (2D) Lennard– Jones (LJ) disks. Each LJ disk has two arms pointing in opposite directions which can associate with arm of another molecule (see Figure 1) to form dimers and chains. Mathematically the interaction between two particles is a sum of a standard Lennard–Jones potential and an associative term which mimic formation of bonds

| (1) |

Figure 1.

The molecules of two dimensional chain forming fluid. Particles associate the strongest when arms are collinear and the distance between two particles is equal to ra.

Here rij is the distance between disk centers of molecules i and j, denotes the vector representing the coordinates and the orientation of the ith particles and of jth respectively. The LJ potential is calculated as

| (2) |

by εLJ being the well–depth of the potential and σLJ the contact parameter. The associative part between molecules is obtained by

| (3) |

εa = −1 is an energy parameter of association, ra is a characteristic distance of associative interaction. is the unit vector along and are the unit vectors representing the direction of kth and lth arm of the ith and jth particle respectively. Further, the G(x) is an unnormalized Gaussian function

| (4) |

The strongest association occurs when the arm of one particle is collinear with the arm of another particle and particles are on distance ra from each other (see Figure 1). The LJ well–depth εLJ is one–tenth of associative interaction energy (εa). The width of Gaussian (σ = 0.085ra) is small enough that it is not possible to have more than one association per arm.

3. Theory

3.1. Thermodynamic perturbation theory

The Helmholtz free energy, A, of the system is the key quantity in TPT[2] and must be calculated first. Here, this quantity for a system consisting of N monomers at temperature T is written as

| (5) |

Aa is association’s contribution to free energy, ALJ is the Helmholtz free energy of Lennard–Jones reference system and kB is Boltzmann’s constant. ALJ can be calculated using the Barker– Henderson perturbation theory [1] with hard disks (HD) as a reference system.

| (6) |

ρ is the total number density of monomers, AHD the HD Helmholtz free energy and gHD(r) HD pair correlation function. The HD Helmholtz free energy is calculated following equation provided by Scalise et al [24]

| (7) |

is the packing fraction and d the diameter of hard–disk reference system [1]. For gHD (r) we used the expression of Gonzalez et al [25]. The Helmholtz free energy contribution of the association was determined using procedure proposed by Jackson et al [26], which was originally derived by Wertheim [2], in the following form

| (8) |

where x is the fraction of molecules not bonded at particular arm and is obtained from the mass–action law [2]

| (9) |

Δ is an integral of an orientationally averaged Mayer function for the associative part of potential, f̄a(r), and correlation function of reference system [2, 26]

| (10) |

The pair distribution function of LJ reference system, gLJ(r), is obtained by solving the Percus–Yevick equation for Lennard–Jones disks. Other thermodynamic properties can be calculated from the Helmholtz free energy using standard thermodynamic equations [1].

3.2. Integral equation theory

The thermodynamic perturbation theory is simple to use, but can only provide information about the thermodynamics. It is lacking information about the structural properties of the system. On contrary, the integral equation theory can provide details about both properties, structural and thermodynamics. Here, we use the orientationally averaged version of the multidensity Ornstein–Zernike (OZ) equation with the polymer Percus–Yevick (PPY) closure [2, 17, 18, 8]. The multidensity OZ equation in Fourier space is written as

| (11) |

where ĥ(k) and ĉ(k) are the matrices whose elements are the Fourier transforms of the total correlation function, hij(r), and direct correlation function, cij(r), respectively. The correlation functions in Wertheim’s theory are between particles with different number of formed bonds. The indices i and j denote the bonding states of the corresponding particles and assume the values 0 for non-bonded particle or 1 for once bonded (h00 is correlation between two non-bonded particles, h11 between two bonded and h01 between non-bonded and bonded particles). Note that in theory we neglect correlation functions with two bonds. Furthermore, ρ is the matrix containing the partial densities. Matrices can be explicitly written as

| (12) |

w stands for either the h or c correlation function, and ρ is written as [8]

| (13) |

The coefficients 2 result from the reduction of the dimensionality of the OZ equation. In order to solve the multidensity Ornstein–Zernike an appropriate additional (closure) relation between h and c correlation functions is needed. In present study we applied the polymer Percus–Yevick closure [2, 17, 18, 8]

| (14) |

where yij(r) = tij(r) + δ0iδ0j, tij(r) = hij(r) − cij(r), x is the fraction of not bonded particles at one particular arm, fLJ(r) = eLJ(r) − 1 and . As before in TPT, f̄a(r) is the orientationally averaged Mayer function for the associating part of the potential and x can be calculated from mass action law[8]. The total pair distribution function g(r) is obtained by summing up the partial distribution functions

| (15) |

where gij(r) = hij(r)+δi0δj0. Once partial pair distribution functions are known the thermodynamic properties can be calculated using equations reported before [8, 27, 28, 29].

We used a direct iteration method to solve the OZ equation together with the polymer PY closure. The forward and inverse Bessel–Fourier transforms, needed to couple the correlation functions in real and Fourier spaces, have been carried out using the method developed by Talman [30]. This method allows us to sample efficiently both the rapidly varying part of the correlation functions at small distances and the long ranged part using a relatively small number of the grid points, n = 1024.

4. Monte Carlo computer simulation

The Monte Carlo simulations were done in grand canonical ensemble (constant μ, V, and T) to get results that were used to test the both theories. To mimic an infinite system of particles we used periodic boundary conditions and the minimum image convention in all simulations that were started from random configurations. In one simulation cycle we tried to translate and rotate each particle and to make as many insertions or removals as were averaged number of particles in system. In each move we randomly tried to translate or rotate random particle or insert new or remove random particle. Probabilities for translation, rotation and exchange of particles were the same. The simulations were allowed to equilibrate for 50000 cycles and averages were taken for 20 series each consisted for another 100000 cycles to obtain well converged results. In the system we had from 50 to 200 particles depending on density of the system. Note that this number of particles in 2D is equivalent to about 1000 particles in 3D. Thermodynamic quantities such as energy, rations of particles with different number of bonds were calculated as statistical averages over the course of the simulations [31]. Increasing the number of particles had no significant effect on the calculated quantities of interest.

5. Results and Discussion

The presented results are given in reduced units. The excess internal energy and temperature are measured in the association energy parameter . All the distances are scaled to the Lennard-Jones characteristic contact parameter .

First, we consider how well IET predicts the structure of the dimerising fluid. Shown in Figures 2 and 3 are the pair distribution functions for two different temperatures at different distances of associative points from center of particles and different densities and snapshots for two of these state points. The Monte Carlo results are represented by red solid line and the IET results by green dashed line. Figure 2 shows the pair distribution functions at high reduced temperature, T* = 0.3 and Figure 3 for low reduced temperature, T* = 0.2. For all temperatures, distances and densities, the IET and the Monte Carlo simulation pair distribution functions are in very good agreement for the position of association point at same distance as the contact distance of LJ potential. For larger distances of association points from center of molecules first LJ and association peak are in good agreement while for long ranged order this is no longer true. In the integral equation theory we have orientational averaging which means that the two arms are no longer fixed at angle 180°, but can take any value of angle between them. This is why the chains in IET are not straight as in MC simulations. There is also a small discrepancy at heights of peaks for high densities when packing of chains is important. In these cases LJ peak predicted by IET is to high which is probably due to an approximation in IET and to get better agreement correct bridge graph function should be included in closure. Similar disagreement was observed also for MB model [8]. But nevertheless since agreement was good for most of distances we checked what happens with correlation function at fixed temperature (T* = 0.15) and density (ρ = 0.49) upon varying position of associative part of molecules from center and this is presented in Figure 4. If associative points are at distances below 0.6 then there is no association due to LJ repulsion and pair correlation functions are same as in case of LJ fluid. For distances above 0.6 we can see associative peak at distance of the associative point. Pair correlation also changes since part of molecules is now forming dimers and longer chains. Total correlation function is as we would have it in case of mixture of single particles and dimers and chains with more particles.

Figure 2.

Pair correlation functions for high temperature T* = 0.3 for different densities and at associative point distance (a) ra = 1.0 and ρ* = 0.17; (b) ra = 1.0 and ρ* = 0.626; (c) ra = 1.43 and ρ* = 0.188; (d) ra = 1.43 and ρ* = 0.587;. Results from computer simulations are plotted by red solid line and from IET by green dashed line.

Figure 3.

Pair correlation functions for low temperature T* = 0.2 for (a) ra = 1.0 and ρ* = 0.177; (b) ra = 1.0 and ρ* = 0.759; (c) ra = 1.43 and ρ* = 0.239; (d) ra = 1.43 and ρ* = 0.655; legend as for Figure 2. Snapshots of the system for (e) ra = 1.0 and ρ* = 0.759 and (f) ra = 1.43 and ρ* = 0.239. Green line connect centers of the particles that form associations.

Figure 4.

Pair correlation functions for different distance of patch from center of particle for temperature T* = 0.1 and density ρ* = 0.49. Functions from bottom up (each shifted for 1) are for distances 0.714, 1.0, 1.143, 1.286, 1.429, 1.714 and 2.142.

As next we checked how good are both theories in reproducing thermodynamics properties. We can point out that here, we could make comparison for both theories. First we calculated the internal energy U* and checked how the theories are doing. How good agreement we got is shown in Figure 5. The theories agree with MC simulation data rather well for both values of the temperatures and all values of the distances. Although we can see that IET is doing slightly better job comparing to TPT. Similar thing we observed in our previous work for formation of dimers[14]. Upon the increase of density the internal energy decreases because there are more particles forming dimers and chains. Next we checked how good are theories in predicting the fraction of particles that are not associated (x0), that form one (x1) or two bonds (x2). Comparisons between computer simulations and theories are plotted in Figure 6. Predictions for the fraction are quite very accurate although we can see that both theories which give similar results since they are based on similar assumptions predict more free particles then observed in computer simulations. As consequence of this theory predict less bonded particles. As next we check how theories are doing in chemical potential of molecules. The chemical potential can easily be calculated in TPT while by IET there is no simple formula and one has to do thermodynamic integration to obtain it, this is why we decided to show only comparison of computer simulation data and TPT in Figure 7. Also here we can see very good agreement at all temperature, densities and distances between theoretical results and results obtained by computer simulations. We can expect same kind of agreement also in case of IET due to similar assumptions behind both theories.

Figure 5.

Density dependence of internal energy for different temperatures and associative point distances from center (a) ra = 1.0 and T* = 0.2; (b) ra = 1.0 and T* = 0.3; (c) ra = 1.43 and T* = 0.2; (d) ra = 1.43 and T* = 0.3;. Results from computer simulations are plotted by red symbols, from IET by blue dashed line and from TPT by green long dashed line.

Figure 6.

Density dependence of ratio of free particles for different temperatures and associative point distances from center for (a) ra = 1.0 and T* = 0.2; (b) ra = 1.0 and T* = 0.3; (c) ra = 1.43 and T* = 0.2; (d) ra = 1.43 and T* = 0.3. Results from computer simulations are plotted by symbols, from IET by dotted line and from TPT by solid line.

Figure 7.

Density dependence of chemical potential for different temperatures and associative point distances from center (a) ra = 1.0; (b) ra = 1.43;. Results from computer simulations are plotted by symbols, from TPT by line. Red color is for low temperature T* = 0.2 and green for high temperature T* = 0.3.

6. Conclusions

We have applied two statistical–mechanical theories developed for associated fluids by Wertheim [2, 3] to the two dimensional model of associating fluid. We also generated a set computer simulation data for thermodynamical and structural properties of the model and compare theoretical and computer simulation results. The IET is somewhat more demanding from a computational point of view than the TPT, but both are orders of magnitude more efficient than the Monte Carlo simulations. Both theories reproduce thermodynamics and structural properties of the model for all temperature and density ranges studied rather well.

Highlights.

TPT and IET for two dimensional chain-forming fluid is developed

Thermodynamics and structural properties of the model are studied

Predictions of the theory and simulation appears to be in a reasonably good agreement

Acknowledgments

T. U. are grateful for the support of the NIH (GM063592) and Slovenian Research Agency (P1 0103-0201, N1-0042) and the National Research, Development and Innovation Office of Hungary (SNN 116198).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hansen JP, McDonald IR. Theory of Simple Liquids. Academic; London: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wertheim MS. J. Stat. Phys. 1986;42:459, 477. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wertheim MS. J. Chem. Phys. 1987;87:7323. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nezbeda I. J. Mol. Liquids. 1997;73/74:317. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muller EA, Gubbins KE. In: IUPAC Volume on Equations of State for Fluids and Fluid Mixtures. Sengers JV, Ewing MB, Kayser RF, Peters CJ, editors. Blackwell Scientific; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalyuzhnyi Yu V, Cummings PT. In: IUPAC Volume on Equations of State for Fluids and Fluid Mixtures. Sengers JV, Ewing MB, Kayser RF, Peters CJ, editors. Blackwell Scientific; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverstein KAT, Haymet ADJ, Dill KA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:3166. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urbic T, Vlachy V, Kalyuzhnyi Yu V, Southall NT, Dill KA. J. Chem. Phys. 2000;112:2843. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urbic T, Vlachy V, Kalyuzhnyi Yu V, Southall NT, Dill KA. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;116:723. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urbic T, Vlachy V, Kalyuzhnyi Yu V, Dill KA. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;118:5516. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urbic T, Vlachy V, Kalyuzhnyi Yu V, Dill KA. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;127:174505. doi: 10.1063/1.2779329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urbic T, Vlachy V, Kalyuzhnyi Yu V, Dill KA. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;127:174511. doi: 10.1063/1.2784124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urbic T, Holovko MF. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;135:134706. doi: 10.1063/1.3644934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urbic T. J. Mol. Liq. 2017;228:32. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2016.09.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nezbeda I, Kolafa J, Kalyuzhnyi Yu V. Mol. Phys. 1989;68:143. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nezbeda I, Iglezias–Silva GA. Mol. Phys. 1990;69:767. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang J, Sandler SI. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;102:437. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vakarin EV, Duda Yu Ja, Holovko MF. Mol. Phys. 1997;90:611. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben–Naim A. J. Chem. Phys. 1971;54:3682. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bizjak A, Urbic T, Vlachy V, Dill KA. Acta Chim. Slov. 2007;54:532. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bizjak A, Urbic T, Vlachy V, Dill KA. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;131:194504. doi: 10.1063/1.3259970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dias CL, Ala-Nissila T, Grant M, Karttunen M. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;131:054505. doi: 10.1063/1.3183935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dias CL, Hynninen T, Ala-Nissila T, Foster AS, Karttunen M. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;134:065106. doi: 10.1063/1.3537734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scalise OH, Zarragoicoechea GJ, Gonzalez LE, Silbert M. Mol. Phys. 1998;93:751. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez DJ, Gonzalez LE, Silbert M. Mol. Phys. 1991;74:613. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson G, Chapman WG, Gubbins KE. Mol. Phys. 1988;65:1. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wertheim MS. J. Chem. Phys. 1987;88:1145. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wertheim MS. J. Chem. Phys. 1986;85:2929. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalyuzhnyi Yu V, Stell G, Llano-Restrepo ML, Chapman WG, Holovko MF. J. Chem. Phys. 101:7939. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Talman JD. J. Comp. Phys. 1978;29:35. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frenkel D, Smit B. Molecular simulation: From Algorithms to Applications. Academic Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]