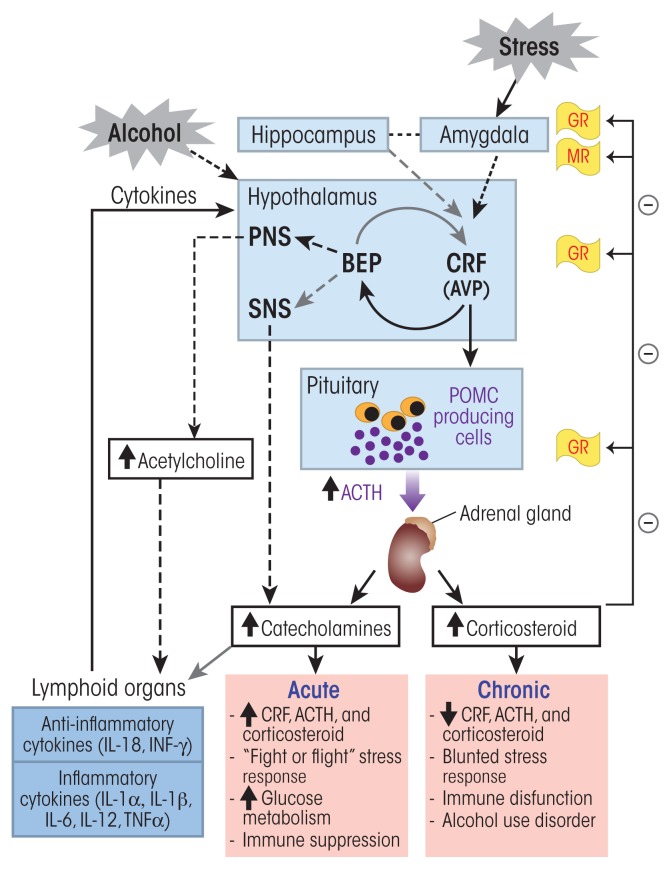

Figure 1.

Alcohol’s effects on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and the stress response. Alcohol can stimulate neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus to release corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and arginine vasopressin (AVP). Stress sensed in the amygdala also elicits a similar activation of this stress response pathway. In the anterior pituitary, CRF stimulates the production of proopiomelanocortin (POMC), which serves as the prohormone for adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). AVP potentiates the effects of CRF on ACTH release from the anterior pituitary. ACTH stimulates cells of the cortical portion of adrenal glands to produce and release glucocorticoid hormones (i.e., cortisol). High levels of glucocorticoids inhibit CRF and ACTH release through a negative feedback by binding to glucocortiocoid receptors (GRs) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs) in various brain regions. Neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus release β-endorphin (BEP), which also regulates CRF release. BEP also acts on the autonomous nervous system and inhibits the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) stress response. CRF, ACTH, and glucocorticoids also act on different organs of the immune system and stimulate cytokine production and release into the general circulation. These cytokines then reach the brain where they trigger a neuroimmune response that sensitizes the stress-response pathway. Acute exposure to alcohol stimulates the HPA-axis stress response and induces suppression of cytokine production. In contrast, chronic exposure to alcohol induces a blunted HPA-axis stress response characterized by an absence of negative feedback control of this pathway and an increase in proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), leading to stress intolerance, immune dysfunction and alcohol use disorder.