Interstitial pneumonia is a life-threatening clinical manifestation of human cytomegalovirus (hCMV) infection. In particular, it can be deadly in patients with hematopoietic malignancies who undergo hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) in whom a ‘window of risk’, which is defined by transient immunodeficiency, occurs between hematoablative therapeutic treatment and immunological reconstitution. As few clinical studies have addressed the underlying mechanisms for this phenomenon, a mouse model of HCT and murine cytomegalovirus (mCMV) infection has been established and has revealed a key role for antiviral CD8+ T cells in controlling pulmonary infections. Using this mouse model, recent studies have provided evidence for the role of mast cells (MC) in more efficiently recruiting antiviral CD8+ T cells to CMV-infected lungs in a process that involves the release of CCL5, a chemokine. MC were found to be direct cellular targets of murine CMV infection and could be activated and degranulated by two mechanisms: the rapid degranulation requiring TLR3/TRIF signaling in non-MC cells and a delayed TLR3/TRIF-independent mechanism. Here, we provide evidence showing that TLR3/TRIF-independent MC activation by CMV is the dominant mechanism in controlling pulmonary infection.

As human cytomegalovirus (hCMV) can establish a life-long latent infection, which under immunocompromised conditions carries a risk of reactivation to recurrent productive infection with multiple organ manifestations, it represents a major risk to patients at transplantation centers worldwide who are solid organ transplantation (SOT) or hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) recipients. In particular, the lungs of HCT recipients are susceptible to CMV disease and have a high risk of developing lethal interstitial pneumonia if left untreated. As CMVs are strictly host species-specific, hCMV cannot be studied in animal models. The mCMV model has reproduced most aspects of hCMV pathogenesis that are observed in patients. Specifically, the lungs represent a major site of CMV latency, reactivation, and pathogenesis in both hCMV-infected humans and mCMV-infected mice.1, 2, 3, 4 In general, the animal model has been instrumental in mimicking hCMV disease to address principles of CMV–host interactions5 and to test new strategies for therapeutic intervention, such as cytoimmunotherapy,6 by focused experimental studies.

Using the murine mCMV model, antiviral CD8+ T cells were found to be more efficiently recruited to infected lungs by the chemokine CCL5.7 This finding has clinical relevance because MC contribute to the control of pulmonary CMV infection by recruiting protective leukocytes. Our present investigations into the activation of MC degranulation by mCMV have revealed two mechanisms (Figure 1): a rapid, TLR3/TRIF-dependent mechanism characterized by early MC degranulation that could be detected ex vivo after 4 h in vivo sensitization by intraperitoneal mCMV infection (Figure 1, top), and a slower TLR3/TRIF-independent mechanism that could be detected in MC under similar conditions at 24 h post-infection (Figure 1, bottom).8 Although the requirement for TLR3/TRIF signaling-dependence for degranulation is certain, other aspects diagramed for the 4-h mechanism shown in Figure 1 (top) are only hypothetical. Importantly, reconstitution of C57BL/6 congenic MC-deficient KitW-sh/W-sh mice with donor bone marrow-derived MC from congenic TLR3−/− mice still revealed TLR3/TRIF signaling-dependence of degranulation, which demonstrated that TLR3/TRIF signaling is not required in the MC themselves but instead occurs in another cell type that must be able to very rapidly deliver an MC-activating signal or ‘alarmin’.

Figure 1.

A diagram of the two mechanisms that can induce MC degranulation triggered by mCMV infection. GFP, green fluorescent protein.

In a search for this activating signal producing cell type, NK cells and F4/80+ macrophages were excluded from the candidate list,8 while its positive identification is pending. A subpopulation of dendritic cells (DC) may qualify as a candidate because mCMV can infect DC, but this also applies to mesothelial cells that line the peritoneal cavity and express various TLRs, including TLR3.9 The latter possibility is difficult to address experimentally; to the best of our knowledge, TLR3 cannot be selectively deleted in mesothelial cells. The short 4-h term available to infect the unknown cell type, deliver the putative alarmin, and trigger MC degranulation suggests that the potential dsRNA ligand of TLR3 may be directly delivered to the endosomal compartment with the virion during the viral entry process. The identification of the proposed alarmin is also pending and remains challenging, as a wide array of known alarmins, including IL-33, depend on MyD88 signaling, which we have shown to be not involved in MC degranulation.8 Another problem was that GFP-reporter protein expression was still low at 4 h, which made it difficult to convincingly demonstrate that degranulation occurs selectively in infected MC.7 We nevertheless propose this to be the case because the low percentage of degranulating MC7 argues against an MC infection-independent degranulation of all MC. We are currently pursuing the idea, diagramed in Figure 1 (top), that 4 h of viral gene expression is not sufficient to trigger MC degranulation by viral proteins alone but that conditioning of MC by a TLR3/TRIF signaling-dependent danger signal cooperates with viral gene products to trigger degranulation.

The mechanism of TLR3/TRIF-independent delayed MC degranulation, which could be detected 24 h after intraperitoneal infection, is much more straightforward (Figure 1, bottom). MC were found to be infected in vivo, and, importantly, degranulation was clearly restricted to infected MC, which exhibited a FcεRI+CD117+CD107a+GFPhigh phenotype.7, 8 Viral gene expression was not restricted to the reporter gene, but infection of MC was found to be productive, which promoted the release of infectious virus and spread of infection to other cell types in various host organs.8, 10 We therefore propose that viral gene products expressed beyond 4 h are sufficient to trigger MC degranulation in a TLR3/TRIF-independent manner.

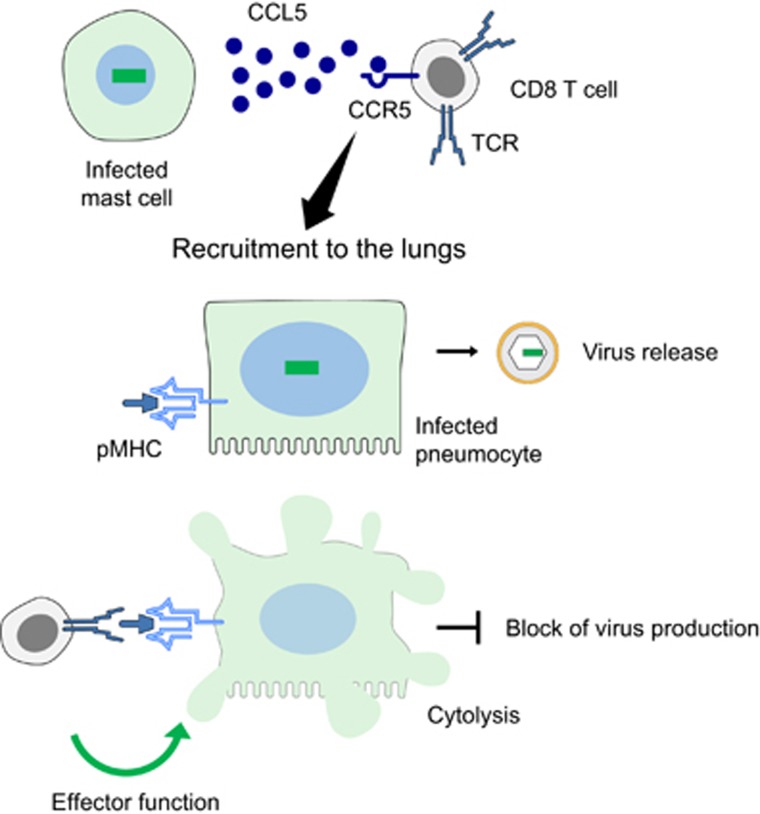

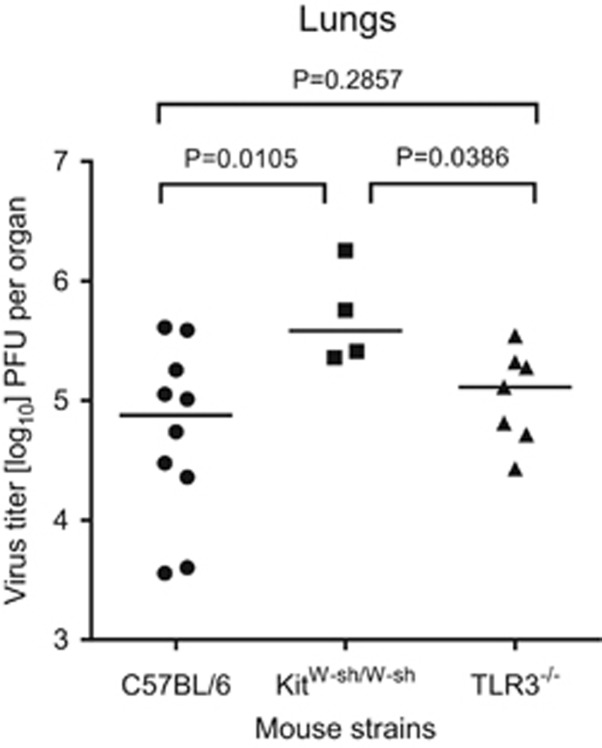

On the basis of previous studies, it remained unclear whether both mechanisms of MC degranulation are required to achieve maximal control of pulmonary infection by enhanced recruitment of CD8+ T cells to the lungs (Figure 2)7 or whether either of the mechanisms would be of preferential importance. This question can be addressed by testing pulmonary infection in TLR3−/− mice in which the mechanism of TLR3/TRIF-dependent degranulation is genetically excluded. Control panels (shown in Figure 3) reproduce and confirm the previously described MC-dependence of antiviral control in the lungs,7 as revealed by increased virus titers in MC-deficient KitW-sh/W-sh mice compared with virus titers in the congenic MC-sufficient C57BL/6 mice. Clearly, virus titers in MC-sufficient TLR3−/− mice were significantly lower than those in MC-deficient ‘sash’ mutants and were not different to those in MC-sufficient C57BL/6 mice. In conclusion, TLR3 signaling, and thus the TLR3/TRIF-dependent mechanism of rapid MC degranulation, is dispensable for the function of MC in the control of pulmonary mCMV infection.

Figure 2.

A diagram of the control of pulmonary infection by CD8+ T cells recruited to the lungs by MC-derived CCL5. CCR5, C–C motif chemokine receptor 5. TCR, T cell receptor. pMHC, viral antigenic peptide(s) presented by major histocompatibility complex class-I protein(s) for recognition by the TCR.

Figure 3.

MC-dependent control of pulmonary infection. Mice of the indicated MC-sufficient (C57BL/6, TLR3−/−) or MC-deficient (KitW-sh/W-sh) genotypes were infected intravenously with 106 plaque-forming units (PFU) mCMV, and virus titers in the lungs were determined on day 10. Symbols represent data from individual mice and median values are indicated. P-values were calculated from log-transformed data using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction to account for unequal variances. Differences between means are considered to be significant for P<0.05.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Michael Stassen and Ann-Kathrin Hartmann of the Institute for Immunology for sharing their expertise in MC biology. Ethics statement: The animal research protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Landesuntersuchungsamt Rheinland-Pfalz according to German Federal Law §8 Abs. 1 TierSchG, permission no. 23 177-07/G09-1-004.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Reddehase MJ, Weiland F, Münch K, Jonjic S, Lüske A, Koszinowski UH. Interstitial murine cytomegalovirus pneumonia after irradiation: characterization of cells that limit viral replication during established infection of the lungs. J Virol 1985; 55: 264–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthesen M, Messerle M, Reddehase MJ. Lungs are a major organ site of cytomegalovirus latency and recurrence. J Virol 1993; 67: 5360–5366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz SK, Rapp M, Steffens HP, Grzimek NK, Schmalz S, Reddehase MJ. Focal transcriptional activity of murine cytomegalovirus during latency in the lungs. J Virol 1999; 73: 482–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podlech J, Holtappels R, Pahl-Seibert MF, Steffens HP, Reddehase MJ. Murine model of interstitial cytomegalovirus pneumonia in syngeneic bone marrow transplantation: persistence of protective pulmonary CD8-T-cell infiltrates after clearance of acute infection. J Virol 2000; 74: 7496–7507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddehase MJ. Mutual interference between cytomegalovirus and reconstitution of protective immunity after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Front Immunol 2016; 7: 294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtappels R, Böhm V, Podlech J, Reddehase MJ. CD8 T-cell-based immunotherapy of cytomegalovirus infection: proof of concept provided by the murine model. Med Microbiol Immunol 2008; 197: 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert S, Becker M, Lemmermann NA, Büttner JK, Michel A, Taube C et al. Mast cells expedite control of pulmonary murine cytomegalovirus infection by enhancing the recruitment of protective CD8 T cells to the lungs. PLoS Pathog 2014; 10: e1004100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M, Lemmermann NAW, Ebert S, Baars P, Renzaho A, Podlech J et al. Mast cells as rapid innate sensors of cytomegalovirus by TLR3/TRIF signaling-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Cell Mol Immunol 2015; 12: 192–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung S, Chan TM. Pathophysiological changes to the peritoneal membrane during PD-related peritonitis: the role of mesothelial cells. Mediators Inflamm 2012; 2012: 484167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podlech J, Ebert S, Becker M, Reddehase MJ, Stassen M. Lemmermann NAW. Mast cells: innate attractors recruiting protective CD8 T cells to sites of cytomegalovirus infection. Med Microbiol Immunol 2015; 204: 327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]