Abstract

In the rapidly growing field of spintronics, simultaneous control of electronic and magnetic properties is essential, and the perspective of building novel phases is directly linked to the control of tuning parameters, for example, thickness and doping. Looking at the relevant effects in interface-driven spintronics, the reduced symmetry at a surface and interface corresponds to a severe modification of the overlap of electron orbitals, that is, to a change of electron hybridization. Here we report a chemically and magnetically sensitive depth-dependent analysis of two paradigmatic systems, namely La1−xSrxMnO3 and (Ga,Mn)As. Supported by cluster calculations, we find a crossover between surface and bulk in the electron hybridization/correlation and we identify a spectroscopic fingerprint of bulk metallic character and ferromagnetism versus depth. The critical thickness and the gradient of hybridization are measured, setting an intrinsic limit of 3 and 10 unit cells from the surface, respectively, for (Ga,Mn)As and La1−xSrxMnO3, for fully restoring bulk properties.

Surface versus bulk effects in electronic structure of spintronics materials are crucial to their applications but are yet well understood. Here the authors experimentally determine the critical thickness that defines the crossover of electron hybridization between surface and bulk for two prototype spintronics materials.

The effectiveness of electron hybridization in solids and its competition with Coulomb interactions plays a fundamental role in novel physical phenomena, often termed as quantum properties1,2. In the context of spintronics, magnetic and electronic reconstructions at interfaces have been often reported, with their origin lying in the delicate interplay between charge, spin and orbital degrees of freedom1,2,3,4,5. Looking at the strength of electron hybridization and localization, near a surface or interface the reduced translational symmetry breaks or severely alters the electronic properties with important consequences for, for example, the magnetic order parameter, transition temperature and metallic/insulator character, thus potentially limiting the achievement of the desired performance in interface-based devices6,7,8. Moreover, surface- and defect states play critical roles in mediating ferromagnetism, due to the modified chemistry of the first top layers.

Prototypical spintronics systems displaying such effects are the rare-earth-doped manganites, in particular metallic La1−xSrxMnO3 (LSMO), and the most representative diluted magnetic semiconductor, (Ga,Mn)As. In both systems, the relationship between electronic reconstruction and magnetic properties and the competition between electron localization and hybridization are relevant ingredients in determining their Curie temperature (TC) and ferromagnetic state5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. In LSMO, the mechanism and the reason for the modified electronic properties of the surface region are still open questions; in (Ga,Mn)As a carrier depletion zone up to 1 nm has been found in the vicinity of the surface, with modified ferromagnetic order11. Moreover, a remarkable example of altered electronic properties has been reported in the so-called magnetic ‘dead layer’ at the surface of otherwise ferromagnetic bulk systems13,14,15,16,17.

To date, bulk sensitive techniques, exploiting the combination of aberration-corrected transmission electron microscopy and electron energy loss spectroscopy was recently able to quantify the role of the charge-transfer screening length at the interface LSMO/PZT (lead zirconate titanate)17, and revealed interfacial electronic reconstruction and a change in TC near the metal–insulator transition in both LSMO/STO and (Ga,Mn)As/GaAs (refs 11, 18). Furthermore, surface-sensitive tools, such as angular resolved photoemission spectroscopy (PES) and scanning probes, gave clear indications of a negligible coherent spectral weight at the Fermi level in bilayer LSMO crystals, with a more fragile metallic and magnetic character at the surface than in the bulk16,19.

Although general agreement has been reached on the observation that both metallicity and ferromagnetism of these systems are reduced at the surface, the determination of the crossover between surface and bulk properties, that is, what the ‘critical’ thickness of such an effect is, and whether the crossover is smooth or abrupt, needs a more complete, and preferably quantitative, description, with particular attention to the modification of the bulk electronic properties when approaching the surface.

Here we report results obtained on thin films of metallic LSMO (with x=0.33 and x=0.35) and of (Ga,Mn)As (with Mn doping between 8 and 13%) using core-level X-ray PES. The large tuneability of the photon energy offered by synchrotron radiation is exploited to significantly vary the information depth from the surface region (<10 Å, corresponding to a few atomic layers) down to the bulk (>100 Å; refs 20, 21). We provide direct and quantitative information of the evolution from metallic (bulk) to insulating (surface) character of these materials, together with a clear indication of the behaviour of hybridization/localization of the bulk electronic states upon both doping and depth. Core-level photoemission in the hard X-ray regime (hard X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (HAXPES), with hv>2 keV) supported by model calculations provides an element-specific spectroscopic fingerprint of the electron hybridization. Distinctly different electron-screening channels exist at the surface and in the bulk, with the bulk one severely suppressed near the surface, where a stronger localization is found. Moreover, the bulk-like metallicity gradually decreases across a thickness of almost 10 unit cells (u.c.) and more than 2 u.c. (for LSMO and (Ga,Mn)As, respectively), eventually disappearing at the surface. Our findings not only deepen the comprehension of interface physics but also have a direct impact on tailor-made functionalities in new devices.

Results

Variable depth information via PES

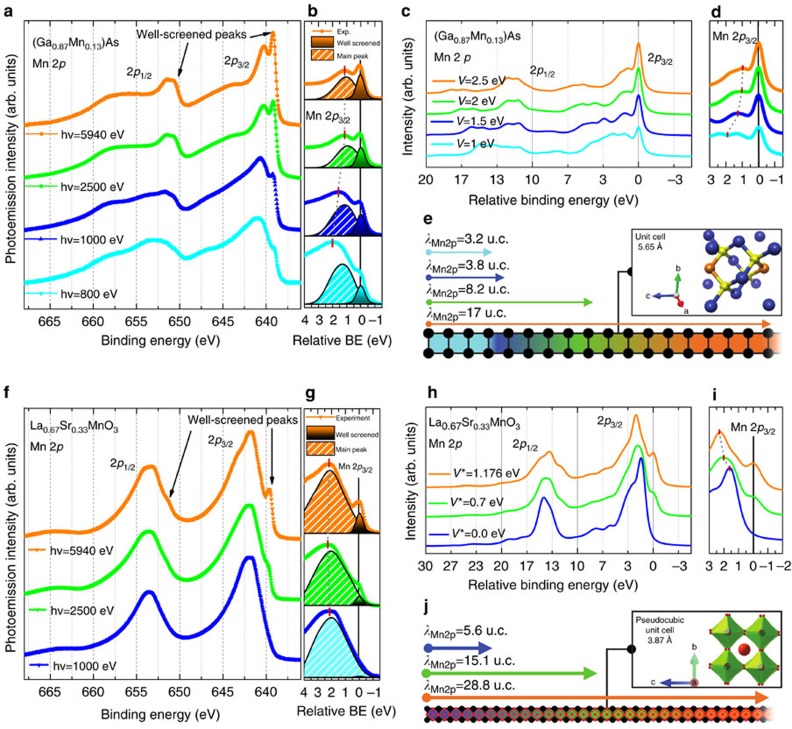

Thin films of LSMO (doping value x=0.33 and x=0.35, grown on LSAT(100) and SrTiO3(100)) and of (Ga,Mn)As (Mn doping between 8 and 13%, grown on GaAs(100)) were measured. Figure 1 shows the Mn 2p core-level spectra measured for (Ga,Mn)As (panels a and b) and LSMO (panels f and g) epitaxial films, as a function of increasing photon energy, that is, with increasing probing depth20,21. The lattice structures are sketched in Fig. 1 e,j, together with the depth information accessible versus photon energy. Details of growth and characterization can be found in the Methods section and Supplementary Information. Additional low binding energy (BE) features, labelled as well-screened satellites, are clearly observed for both spin–orbit partners when entering the regime of HAXPES, in agreement with previous reports22,23,24,25. Such features are severely reduced or absent at the lower photon energies, that is, for enhanced surface sensitivity, as highlighted in panels b and g, where the evolution of the intensity of the low-BE satellites versus photon energy is quantified by a line shape analysis (Supplementary Fig. 13). It is important to emphasize that the critical depth at which the satellite intensity appears is much larger for LSMO compared to (Ga,Mn)As, although results are obtained for the same element, Mn, and minimal differences in surface roughness are found (Supplementary Figs 10–12). We observe that the energy separation between the well-screened satellites and the main peak varies versus photon energy, as highlighted by red thick marks. We further note that in both systems the intensity increase of the low-BE satellites is gradual, with no indication of a sharp transition.

Figure 1. Depth-dependent PES results.

(a,b) Photon energy-dependent Mn 2p core-level spectra of (Ga,Mn)As (13% Mn-doped GaAs, measured with linear polarization at T=300 K) and (f,g) Mn 2p core-level spectra of LSMO (La0.67Sr0.33MnO3, measured with linear polarization at T=210 K). The spectra were shifted vertically for ease of comparison after integral background subtraction. The multiplet structures of the 2p1/2 and 2p3/2 are clearly resolved. The arrows indicate the position of the well-screened satellites for each spin–orbit partner. (b,g) Expanded view of the Mn 2p3/2 peak around 640 eV BE ((b) (Ga,Mn)As, (g) LSMO). The evolution of the well-screened peak intensity is shown as a function of increasing photon energy (dotted curves are experimental spectra, filled peaks are the result of a fitting procedure described in the Supplementary Information). Note that at hv=1,000 eV the well-screened intensity is clearly present in (Ga,Mn)As, while almost absent for LSMO. Calculated spectra for (Ga,Mn)As (c) and LSMO (h) from models described in the text with varying hybridization parameter V and V* for (Ga,Mn)As and LSMO, respectively; the spectra are shifted vertically for clarity. (d,i) Close-up of the Mn 2p3/2 peak; the thick marks indicate the different energy separations between main and satellite peak versus hybridization value V and V*. (e,j) Sketch of the depth of information and crystal structures of (Ga,Mn)As and LSMO. The length of the arrows is proportional to the inelastic mean free path λIMFP in Mn and attenuation length, calculated as defined in refs 20, 21, where the information depth corresponds to three times the inelastic mean free path λIMFP. The values of λIMFP indicate the number of u.c. probed with the respective photon energy, identified by the colour code.

Quantifying hybridization/localization of electronic states

The term well-screened for the low-BE features seen in Fig. 1 is strictly linked to the screening of electrons after a core hole is created in the photoemission process. A sketch of the energy levels of ground and final states is presented in panels a and c of Fig. 2 for (Ga,Mn)As and LSMO, respectively. The BE of each possible final state depends on how effective the core hole is screened by the valence electrons, and taking into account the hybridization V between valence and conduction electrons, a state can be pulled down in energy by an amount Q due to the core–valence Coulomb interaction. In this condition, the core–hole potential creates an excitonic state with a hole in the 3d band. In the well-screened state a valence electron, via hybridization V, fills this hole; in the poorly screened state, this hole stays empty.

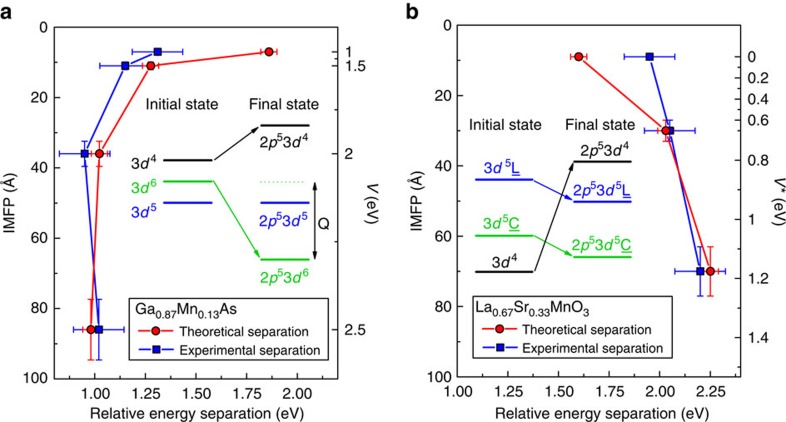

Figure 2. Evolution of the hybridization parameters V and V*.

Comparison between experimental and theoretical data regarding the energy separation between well-screened and main peaks. The experimental data of (Ga,Mn)As (blue filled squares, a) and LSMO (blue filled squares, b) are plotted versus the calculated inelastic mean free path (left vertical axis) and compared with the theoretical data (red filled circles in both panels) corresponding to the value of the hybridization parameter V and V* (right vertical axis in eV). Lines through the points are guides for the eye. The horizontal error is estimated as the measured experimental energy resolution, which is always larger than the positioning uncertainty of the fitting functions. The vertical error is the 10% of the IMFP value corresponding to each photon energy, according to the TPP-2M formula. The value of mean escape depth λIMFP is calculated as the product of the inelastic mean free path and the cosine of the angle between the normal to the sample surface and the photoelectron direction (θ≃3°). The separation between the peaks follows the trend predicted by theory. In the insets: Schematic energy level diagram of the 3d configurations before hybridization in the initial and final state (in presence of a core hole), following the theoretical models described in the text. The configuration-averaged energies of the ionic configurations have been used, neglecting multiplet, crystal field, and hybridization effects in the diagram. It should be kept in mind, however, that all these effects shift and spread the levels.

A theoretical understanding of the satellites features in core levels of strongly correlated systems dates back several decades starting from observations in 4d- and 4f-based materials26,27,28, followed by more general models for 3d transition metals29,30. More recently, well-screened satellites have been reported as bulk-only features in core-level HAXPES spectra of 3d transition metal oxides (vanadates, manganites) and magnetic diluted systems22,23,24,25,31,32. Following these results, improved theoretical approaches have been presented, based on multisite cluster model, Anderson impurity model and effective coupling at the Fermi level24,33,34,35. By quantifying the variation of the hybridization parameter, the here-performed model calculations provide evidence of the link between the satellites and the metallic/insulating character of the system. Calculated spectra are shown in Fig. 1 for (Ga,Mn)As (panels c,d) and LSMO (panels h,i).

Comparison with calculations in Mn-doped GaAs

Photoemission spectra for the transitions 3dn→2p53dn in (Ga,Mn)As are calculated using an Anderson impurity model, taking into account configuration interaction in the initial and final states33. A scheme of the initial- and final-state configuration is presented in the insets of Fig. 2. In the calculation, Δ=E(d6L)−E(d5) is the ligand-to-3d charge-transfer energy, U is the 3d–3d Coulomb energy and Q is the 2p–3d Coulomb energy (we will omit L in the notation, as there presence is clear from charge neutrality). The configurations are mixed by hybridization, which is described by a parameter V (see Methods). The Δ, U and Q values give the relative energies of the average configuration as E(3d4)=−Δ+U=3 eV, E(3d5)=0 eV and E(3d6)=Δ=1 eV, and for the final state as E(2p53d4)=−Δ+U+Q=8 eV, E(2p53d5)=0 eV and E(2p53d6)=Δ−Q=−4 eV. This means that, while the ground state has primarily d5 character, the lowest final state has mainly d6 character. The final state 2p53d6 is pulled down below 2p53d5 by an energy ∼Q. Thus, the order of the energy levels 3d5 and 3d6 is reversed in the final state, which means that the 2p53d5 is a poorly screened state and the 2p53d6 a well-screened state with an extra d-electron. Here we adopt values Δ=1 eV, U=4 eV, Q=5 eV similar as for (resonant) PES36,37,38 and X-ray absorption spectroscopy39 of (Ga,Mn)As, In Fig. 1c one observes that a good agreement with the ‘bulk’ spectrum (orange curve in Fig. 1a) is obtained with Δ=1 eV, U=4 eV, Q=5 eV and V=2.5 eV, confirming the coexistence of localized and itinerant electrons in the bulk. The low-energy PES spectrum, representative of the more-localized surface region, is well reproduced with V=1.5. Overall, a good agreement is found between experiment and calculation concerning the change of intensity and the relative position of satellite and main peak. The main difference with the experiment is that the calculation overestimates the intensity of the poorly screened peak. This is because the model does not include all possible additional screening channels, which can take away intensity from the screened peak, smearing out the calculated leading peak.

Comparison with calculations in LSMO

The Mn 2p HAXPES spectra were calculated within the extended configuration interaction model, described in previous lines of work24,34. As basis states, configurations 3d4, 3d5L and 3d5C were used. The 3d5C represents the charge transfer (CT) between Mn 3d and the doping-induced coherent state at EF, labelled C. An effective coupling parameter V* for describing the interaction strength between the Mn 3d and coherent state is introduced, analogous to the Mn 3d-O 2p hybridization V. Two parameters are varied: the CT energy between Mn 3d and the new C states (Δ*) and the hybridization between Mn 3d and coherent states (V*). Except for these two parameters, all other parameter values are fixed. In Fig. 1h calculated spectra for three different hybridization values V* are shown. Both the low-energy feature around 640 eV BE and a broad shoulder appearing at 644 eV with large probing depth are well reproduced by the calculations. The well-screened peak in the calculation is analysed to originate from the 2p53d5C configuration of the final state, and increases in intensity with increasing V*.

The evolution of satellite peaks in LSMO is qualitatively similar yet quantitatively different with respect to (Ga,Mn)As: a sizeable intensity of the low-BE feature in LSMO is found at much larger depth, as indicated in Fig. 1e,k. It is important to underline that the well-screened peaks correspond to the lowest-energy state. Compared to the higher-energy states, this low-energy state is less mixed with other states, which means their linewidth should be narrower. This characteristic is confirmed convincingly by the experimental results.

A further confirmation that the well-screened peak is a spectroscopic fingerprint of electron hybridization, that is, a measure of the truly bulk metallic character, is found from the comparison between the experimental data and theoretical predictions regarding the energy separation between main peak and satellite peak. In (Ga,Mn)As (Figs 1b,d and 2a), the theoretical description correctly explains the strong decrease in the energy separation for the main-to-satellite peak (red marks in Fig. 2d) going from V=1.0 eV (surface) to V=2.5 eV (bulk), with a larger discrepancy towards the surface limit. Although a good agreement is found between experiment and theory, theoretical data overestimate the energy separation in the range 1<V<2 eV. Calculations show that the poorly screened peak consists in fact of more than one peak. In the experimental results we plot the energy distance to the broad main peak because the experiment cannot resolve the fine structure as theory does (see Supplementary Information). The same general agreement is also found in LSMO (Figs 1g,j and 2b) with an overall trend for increasing the energy separation between peaks when the hybridization V* increases. The separation between well-screened peak (2p53d5C) and main peak (2p53d5L) peaks increases with Δ* and with the hybridization V* between 3d4 and 3d5C configurations. The strength of hybridization V* also influences their relative intensities. Basically, the smaller value of Δ* forms a peak at much lower BE side. Previous reports for metallic LSMO show that the separation between the main peak and the well-screened feature increases with hole-doping until x=0.4, and reduces for x=0.55 (ref. 22). In addition, this behaviour matches well with the metallic/magnetic character owing to the fact that, following the phase diagram, hole-doping with increasing x produces a ferromagnetic phase in LSMO with larger TC and lower resistivity up to x=0.4 (refs 22, 40). Consistent with the decrease of the well-screened feature at low photon energies (Fig. 1f,g), a smaller peak separation suggests a smaller effective hole-doping and a lower metallicity at the surface. It is important to underline that the observed evolution of the energy separation not only confirms the validity of our approach but could also be used as a signature of the competition between localized and delocalized electronic character.

Critical thickness of electronic hybridization

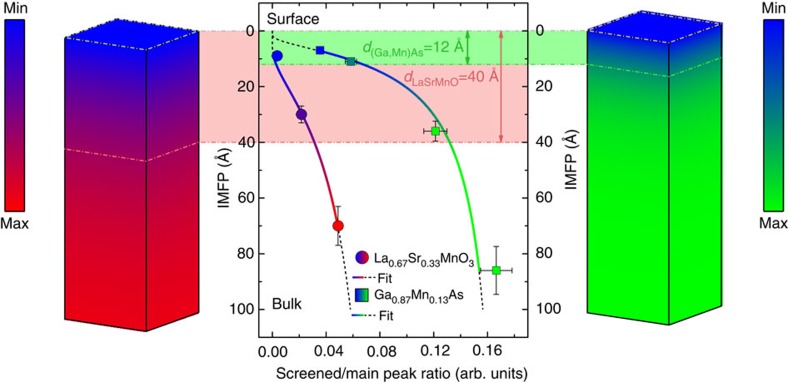

Having ascertained that the presence and the evolution of the well-screened peaks are spectroscopic fingerprints of the electronic hybridization, we now deepen our analysis to a more quantitative aspect. Following the results of Figs 1 and 2, the attenuation of the low-BE satellites versus probing depth can be modelled by a fitting procedure described in the Supplementary Fig. 3 displays the value of the inelastic mean free path (IMFP) λIMFP at different photon energies versus the ratio between the area of the satellite peak and the total area of the Mn 2p3/2 spectrum. Here λIMFP was obtained from the TPP-2M formula for (Ga,Mn)As and LSMO21,41. The curves through the points in Fig. 3 are the best fits to the data of an exponential attenuation function of the form I(λ)=A exp (−B/λ), where A indicates the contribution of the satellite to the total area of the spectrum and B represents the thickness of a surface layer where the screening channel associated to the extra peak is considered as totally absent, that is, a layer fully attenuating the intensity of the satellite present in the bulk. This simple model describes the attenuation of the bulk electronic hybridization when going towards the surface of the solids; hence, the thickness B is a measure of the spatial extension of the modified electronic properties or, more precisely, the depth at which both hybridization and metallicity start to be modified with respect to their bulk values. A sketch of the solids with these two critical thicknesses is presented on the right (GaMnAs) and left (LSMO) sides of Fig. 3. We obtain a value of (12±1) Å for (Ga,Mn)As and (40±2) Å for LSMO, corresponding to more than 2 and almost 10 u.c., respectively. These values should be compared with the 10 Å-thick Mn depletion reported in (Ga,Mn)As (ref. 11), and with X-ray magnetic spectroscopy and transport results on thin LSMO films, where altered ferromagnetism and metallicity have been observed up to 30 Å of thickness from the surface42,43,44,45,46.

Figure 3. Critical thickness determination.

Evolution of the ratio between the area of the extra peak and the main peak as a function of the inelastic mean free path (filled circles for LSMO; filled squares for (Ga,Mn)As). The vertical error bar is calculated, as in Fig. 2, to be the 10% of the absolute value of the IMFP. The horizontal uncertainty is calculated by means of error propagation from the uncertainty on the parameters of the fitting functions. The solid hued lines show the curves obtained by fitting the experimental points with the function I(λ)=A exp(−B/λ). The dashed black lines show the extrapolation of the same functions outside the data range. The light green (red) shaded area shows the value corresponding to the critical thickness, that is, the value of the B parameter obtained from each fit, resulting in 12 Å for (Ga,Mn)As and 40 Å for LSMO. The two blocks on left and right sides, representing respectively LSMO and (Ga,Mn)As, give a three dimensional image of the change of electron hybridization when moving from the bulk to the surface. Dark colours correspond to a zone where hybridization is reduced with respect to its bulk value. The filling is hued from blue to green (red) in the vertical direction according to the fitted function for (Ga,Mn)As (LSMO), with blue corresponding to zero and green (red) corresponding to the maximum value assumed by the function in the range 0–100 Å.

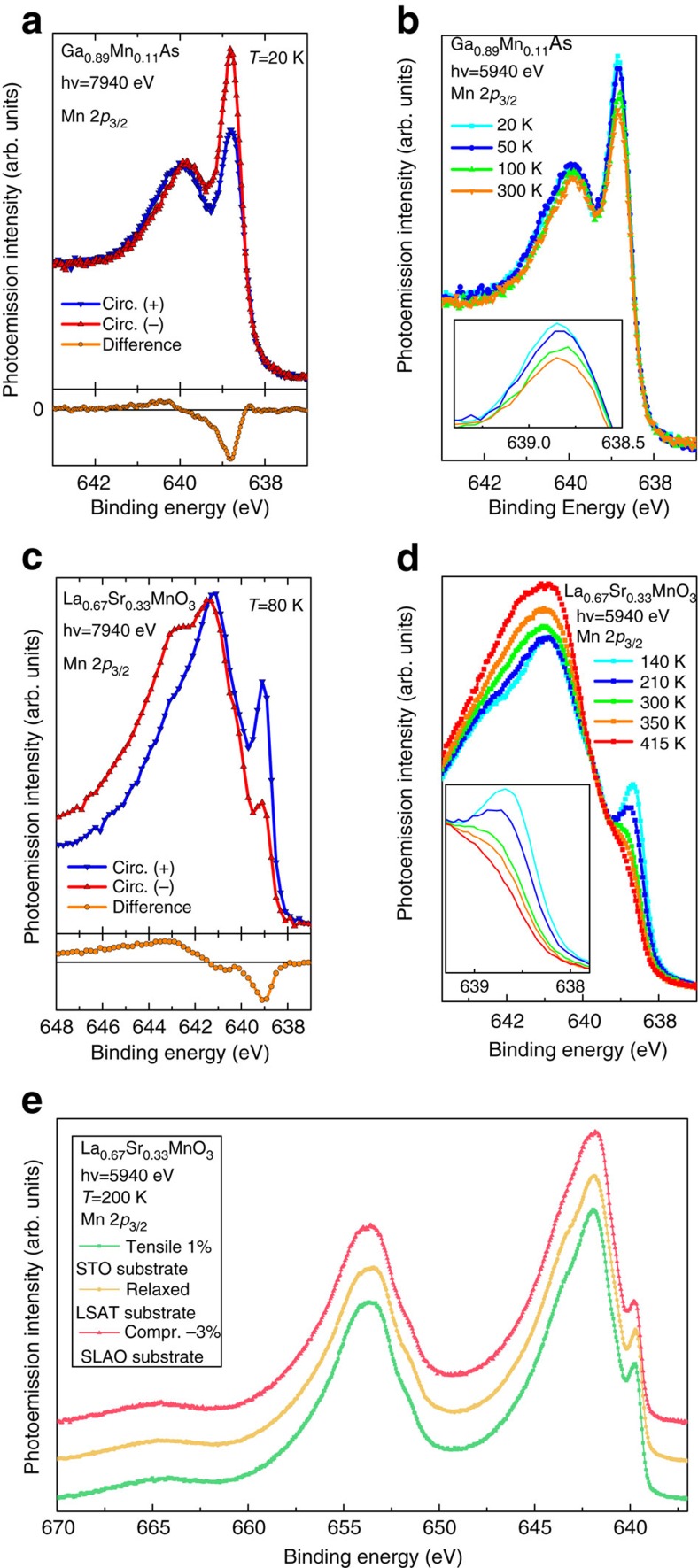

Strain and temperature dependence

Strain-driven interface engineering is a relevant issue for spintronic heterostructure, and recent results have shown that the symmetry breaking induced by lattice strain influences the electron occupancy of the out-of-plane orbitals in the topmost surface layer47. To investigate the effect of strain on our findings, we have measured the critical thickness of bulk metallic screening using the same method of Fig. 3, on LSMO films (100 u.c. thick each) epitaxially grown on (001)-oriented SrTiO3 (STO) and on SrLaAlO4 (SLAO) substrates, producing, respectively, 1% tensile strain and 3% compressive strain (Supplementary Figs 1–8).

As shown in Fig. 4e, strained and unstrained films display the same main spectral features, with the exception of LSMO grown on SLAO, where a slightly broader satellite is observed. Such difference is attributed to the lower Curie temperature of strained films, as explained in the next section. The critical screening thickess obtained from the application of the fitting procedure is 41±7 Å in LSMO/SLAO, while no difference within error bars is found between the tensile-strained LSMO/STO films and the unstrained ones grown on LSAT. These results show that, although sensitive to the change of electronic hybridization across the entire thickness of the film, core-level photoemission does not provide a direct probe of orbital occupancy and/or symmetry breaking at the surface as the X-ray absorption technique used in ref. 47, suggesting that the evolution of the bulk metallic screening across the thickness of the sample could be attributed to dimensionality effects.

Figure 4. Magnetic dichroism and Mn 2p versus temperature and strain.

(a,c) Mn 2p core-level spectra measured with left- and right-circularly polarized X-rays in LSMO (c) and (Ga,Mn)As (a). Differences (open circles) are shown at the bottom of the panels. Note that the largest magnetic signal is located at the energy position of the well-screened satellites. (b,d) Temperature dependence of the Mn 2p3/2 core-level spectra. In LSMO (d), a shoulder is still visible above TC (345 K), while the intensity of the well-screened satellites, responsible of the large dichroism observed, is totally suppressed. In (Ga,Mn)As, (b), the intensity variation of the well-screened satellite is highlighted in the inset. The maximum increase is observed when crossing TC=70 K. (e) Mn 2p core level of LSMO thin films (100 u.c.) grown on three different substrates: SrTiO3 (STO), (LaAlO3)0.3(Sr2TaAlO6)0.7 (LSAT), and SrLaAlO4 (SLAO), measured at hv=5940, eV and T=200 K. Due to the lattice mismatch, STO induces a 1% tensile strain and SLAO a 3% compressive one. Films grown on LSAT are considered as relaxed. No significant difference is observed in their line shape, except a small decrease in intensity in the case of the compressive strain (red spectrum). Calculated critical thicknesses, using the same method of Fig. 3, give 41±7 Å in LSMO/SLAO, while no difference within the error bar is found in the case of LSMO/STO.

We now turn to the influence of temperature on the magnetic properties. Chemical sensitive magnetic information can be obtained by detecting the Mn 2p core-level spectra using left- and-right circularly polarized X-rays (magnetic circular dichroism in HAXPES), as shown in panel a Fig. 4a for (Ga,Mn)As and panel c for LSMO, respectively. A large difference, the magnetic circular dichroism, is observed with the well-known down-up (2p3/2), up-down (2p1/2) line shape32,48,49. It is important to emphasize that, in both systems, the largest magnetic signal is observed at the energy position of the well-screened satellites, confirming the major role of delocalized electrons in establishing the mechanism of ferromagnetism12,23,24,32. Furthermore, Fig. 4b,d shows that the temperature also influences the relative intensities of the well-screened and poorly screened peaks. In (Ga,Mn)As, a clear change in the relative intensity of the main and satellite peaks is visible when crossing TC=70 K, as previously reported23. As for LSMO, the inset of panel d reveals a fine structure of the well-screened satellites, where: (i) a weak shoulder persists above TC (345 K), corresponding to a multiplet structure not directly linked to ferromagnetic properties and (ii) a large decrease of spectral weight is observed, connected to the change of the magnetic order parameter, confirming previous results on La1−xBaxMnO3 (ref. 50). In this regime of doping, the bilayered manganites have a concomitant metal–insulator and ferromagnetic–paramagnetic transition as a function of temperature and the well-screened satellite disappears above TC (ref. 25). It should be noted that the decrease of the well-screened satellite intensity follows a bulk-like behaviour and does not display the well-known rapid decrease usually observed in surface-sensitive results51. Although the largest dichroism, corresponding to the presence of a long-range magnetization, is observed where delocalized states are, a contribution to magnetism is also arising from the rest of the spectrum, that is, localized or poorly screened part. This further corroborates the fact that the magnetism is reduced in absence of the extra-peak screening channel, although not suppressed.

Discussion

We provide clear evidence from the study of two paradigmatic spintronics materials that the electronic hybridization strength varies significantly from its bulk value when approaching the surface layers. The dimensionally dependent role of (de)localized electrons is revealed, affecting both the ferromagnetic and metallic behaviour. Concerning the spatial extension of the altered electronic properties, the interplay between carrier localization and metallicity in (Ga,Mn)As is restricted to the near-surface region (∼10 Å) in agreement with the observed loss of long-range magnetization and Mn depletion leading to a superparamagnetic-like response11. As for LSMO, previous reports suggested the existence of decoupled magnetic and metallic critical thicknesses due to localization effects in thin films, with a larger extension (up to 30 Å) of the metallic thickness42,44,52,53,54. Our results corroborate this hypothesis, giving a quantitative estimate of the crossover thickness range for a film to fully develop bulk-like hybridization values. It is important to emphasize that the spectroscopic fingerprints we have used and modelled are representative of a bulk-only character: the strong attenuation of the well-screened feature measured close to the surface is directly connected to an altered metallicity, yet not suggesting that this metallicity is completely suppressed. Moreover, we have shown that both localized and delocalized electrons contribute to both electronic and magnetic character, opening the perspective of a direct comparison between the critical thickness for the electronic structure with the critical thickness of the magnetic properties. Finally, our data provide evidence that a difference in the overall film properties will be always present due to the reduced dimensionality, hence due to the modified hybridization, especially when the film is not thick enough and/or at interfaces. The depth extension of the surface/interface electronic charge distribution, and its control via atomic-precision growth techniques, will conceivably open alternative routes for engineering complex heterostructures.

Methods

Growth

La0.65Sr0.35MnO3 (LSMO) thin films were grown by molecular beam epitaxy in a dedicated chamber located at the APE beamline (NFFA facility, Trieste, Italy). LSMO films of different doping and thickness have been grown. Samples used in the present report are grown on La0.18Sr0.82Al0.59Ta0.41O3 (LSAT), that is, strain relaxed, and have a thickness of 100 u.c. (≈400 Å), with the c axis oriented perpendicularly to the surface. Growth and characterization of strained films are described in Supplementary Material. The ferromagnetic (Ga,Mn)As films (Mn doping level between 6 and 13%) were grown by molecular beam epitaxy on GaAs substrates using a modified Veeco Gen II system at the University of Regensburg, Germany, with a Mn doping range between 6 and 13%. Samples measured in present report have 200 Å of thickness and 12.5% of doping, unless reported otherwise. (Ga,Mn)As films were measured as-grown, in order to avoid segregation of Mn towards the surface after post-annealing treatment. Details of structural and magnetic characterization can be found in the Supplementary Material.

HAXPES

Photon energy- and temperature-dependent HAXPES experiments were performed at the I09 beamline at Diamond Light Source (Didcot, UK). The beamline’s end station is equipped with a SCIENTA EW-4000 electron energy analyser, mounted with the lens axis perpendicular to the X-ray beam. A grazing incidence geometry (that is, normal photoelectron emission) has been used, that is, 3° angle between the X-ray beam and the surface plane, with an angular and energy resolution better than 0.2° and 20 meV, respectively, resulting in a 30 × 250 μm2 beam footprint on the sample. The position of the Fermi level EF and the overall energy resolution have been estimated by measuring the Fermi edge of a polycrystalline Au foil in thermal and electric contacts with the samples. The overall energy resolution (analyser+beamline) was kept below 250 meV over the entire photon energy range. Magnetic dichroism in HAXPES spectra was acquired at BL19LXU at Spring-8, Japan, equipped with a SCIENTA R4000-10 kV electron energy analyser at grazing incidence geometry (>4° angle between the X-ray beam and the surface plane) and a spotsize of 40 × 500 μm2 on the sample. The overall energy resolution (analyser+beamline) was kept below 400 meV at the selected photon energy.

Calculations

(GaMn)As. Photoemission spectra for the transitions 3dn→2p53dn in (Ga,Mn)As are calculated using an Anderson impurity model, taking into account configuration interaction in the initial and final states26. The wave functions are a coherent sum over dn, dn+1L, dn+2L2,... configurations, where L denotes a hole in the ligand orbitals. The average energies of the initial and final state configurations are taken as points on a parabola, E(dn)=n(Δ−5U)+½ n(n−1)U and E(2p5dn)=E(2p5)+E(dn)−nQ, respectively, where Δ=E(d6L)−E(d5) is the ligand-to-3d charge-transfer energy, U is the 3d–3d Coulomb energy and Q is the 2p–3d Coulomb energy. The configurations are mixed by hybridization with a parameter V=<d|H|L>.

The Hamiltonians, H, for the initial and final states of the Mn atoms are calculated using Cowan’s code55, including tetrahedral crystal-field symmetry (10Dq=−0.5 eV), spin–orbit and multiplet structure but neglecting band structure dispersion. Wave functions are calculated in intermediate coupling using the atomic Hartree–Fock approximation with relativistic corrections and by reducing the Slater parameters to 80% to account for intra-atomic correlation effects. No coherent state near the Fermi level has been included. When V is larger, there will be more weight of the 3d6 configuration in the initial state, resulting in a more intense ‘satellite’ peak at ∼4 eV lower BE than the main peak, giving a d count of 5.2 and ground state of 0.3% d3, 10.0% d4, 60.8% d5, 26.5% d6 and 2.8% d7.

LSMO. A modified Anderson impurity model was used with six configurations as basis states: 3d4, 3d5L and 3d5C. The 3d5C represents the CT between Mn 3d and doping-induced coherent state at EF, labelled C. The V (Γ), Udd and −Udc are the hybridization between the TM 3d and the ligand states, the on-site repulsive Coulomb interaction between TM 3d states and the attractive core–hole potential, respectively. The standard Hamiltonian Hmult describes the intra-atomic multiplet coupling between TM 3d states and that between TM 3d and TM 2p states. The spin–orbit interactions for TM 2p and 3d states are also included. A further term V*, is introduced to account for the ‘coherent’ screening channel at the Fermi level22,40, with an effective coupling parameter accounting for interaction strength with 3d states. The CT energy for such additional state is Δ*. We used a value of U=5.1 Vh for the on-site Coulomb repulsion, Q=5.4 eV for the attractive core–hole potential, Δ*=4.5 eV for the CT energy, 10Dq=1.5 eV for the crystal field and V(eg)=2.94 eV. The reduction factors of V are Rc=0.8, Rv=0.9.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Pincelli, T. et al. Quantifying the critical thickness of electron hybridization in spintronics materials. Nat. Commun. 8, 16051 doi: 10.1038/ncomms16051 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work has been partly performed in the framework of the nanoscience foundry and fine analysis (NFFA-MIUR Italy) facility.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions G.P., T.P. and F.B. conceived the experiment and wrote the paper with contributions from G.v.d.L., M.T., C.H.B. and G. R. All authors discussed the results, commented manuscript and prepared written contributions. F.M.G., P.G. and A.Y.P. grew the films, and R.C. and M.C. characterized samples. G.v.d.L. and M.T. performed the calculations. F.B., V.L., B.G. T.-L.L., C.S., M.O., H.D., A.R. and D.J.P. performed synchrotron radiation experiments and analysed the data.

References

- Awschalom D. D., Bassett C. L., Dzurak S. A., Hu L. E. & Petta R. J. Quantum spintronics: engineering and manipulating atom-like spins in semiconductors. Science 339, 1174–1179 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesin D. & MacDonald A. H. Spintronics and pseudospintronics in graphene and topological insulators. Nat. Mater. 11, 409–416 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibes M. & A. Barthelemy A. Oxide spintronics. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 54, 1003–1023 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Imada M., Fujimori A. & Tokura Y. Metal-insulator transitions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 1039 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Jungwirth T. et al. Spin-dependent phenomena and device concepts explored in (Ga,Mn)As. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 855 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- I. Zutic I., J. Fabian J. & Sarma S. D. Spintronics: fundamentals and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 323 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Dietl T. & Ohno H. Dilute ferromagnetic seminconductors: physics and spintronics structures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 187 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Sato K. et al. First principles theory of dilute magnetic semiconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 2 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- M. Dobrowolska M. et al. Controlling the Curie temperature in (Ga,Mn)As through location of the Fermi level within the impurity band. Nat. Mater. 11, 444 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M. et al. High Curie temperatures at low compensation in the ferromagnetic semiconductor (Ga,Mn)As. Phys. Rev. B 87, 121301(R) (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Sawicki M. et al. Experimental probing of the interplay between ferromagnetism and localization in (Ga,Mn)As. Nat. Phys. 6, 22–25 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Gray A. X. et al. Bulk electronic structure of the dilute magnetic semiconductor Ga1-xMnxAs through hard X-ray angle-resolved photoemission. Nat. Mater. 11, 957–962 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z. et al. A local metallic state in globally insulating La1.24 Sr1.76 Mn2 O7 well above the metal-insulator transition. Nat. Phys. 3, 248–252 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Freeland J. W. et al. Suppressed magnetization at the surfaces and interfaces of ferromagnetic metallic manganites. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 19, 315210 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R. Bertacco R. et al. Surface electronic and magnetic properties of La2/3Sr1/3MnO3 thin films with extended metallicity above the Curie temperature. Phys. Rev. B 78, 035448 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento V. B. et al. Surface-stabilized nonferromagnetic ordering of a layered ferromagnetic manganite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 227201 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurgeon S. R. et al. Polarization screening-induced magnetic phase gradients at complex oxide interfaces. Nat. Commun. 6, 6735 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy J. A. et al. Visualizing the interfacial evolution from charge compensation to metallic screening across the manganite metal-insulator transition. Nat. Commun. 5, 3464 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massee F. et al. Bilayer manganites reveal polarons in the midst of a metallic breakdown. Nat. Phys. 7, 978 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Sacchi M. et al. Quantifying the effective attenuation length in high-energy photoemission experiments. Phys. Rev. B 71, 155117 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Tanuma S., Powell C. J. & Penn D. R. Calculations of electron inelastic mean free paths. IX. Data for 41 elemental solids over the 50 eV to 30 keV range. Surf. Interface Anal. 43, 689–713 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Horiba K. et al. Nature of the well screened state in hard X-ray Mn 2p core-level photoemission measurements of La1-xSrxMnO3 films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 236401 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii J. et al. Identification of different electron screening behavior between the bulk and surface of (Ga,Mn)As Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 187203 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi M. & Panaccione G. in Hard X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (ed. J. C. Woicik) ISSN 0931-5195 (Springer, 2016).

- Offi F. et al. Bulk electronic properties of the bilayered manganite La1.2Sr1.8Mn2O7 from hard-x-ray photoemission. Phys. Rev. B 75, 014422 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Fuggle J., Campagna M., Zolnierek Z., Lasser R. & Platau A. Observation of a relationship between core-level line shapes in photoelectron spectroscopy and the localization of screening orbitals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 1597 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson O. & Schonhammer K. Photoemission from Ce compounds: exact model calculation in the limit of large degeneracy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 50, 604 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Kotani A. & Toyozawa Y. Optical spectra of core electrons in metals with an incomplete shell. I. analytic features. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 35, 1073–1081 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- Van der Laan G., Westra C., Haas C. & Sawatzky G. A. Satellite structure in photoelectron and Auger spectra of copper dihalides. Phys. Rev. B 23, 4369 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Van Veenendaal M. A. & Sawatzky G. Nonlocal screening effects in 2p x-ray photoemission spectroscopy core-level line shapes of transition metal compounds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 2459 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaccione G. et al. Coherent peaks and minimal probing depth in photoemission spectroscopy of Mott-Hubbard systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 116401 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds K. W., van der Laan G. & Panaccione G. Electronic structure of (Ga,Mn)As seen by synchrotron radiation. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 30, 043001 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Van der Laan G. & Taguchi M. Valence fluctuations in thin films and the α and δ phases of Pu metal determined by 4f core-level photoemission calculations. Phys. Rev. B 82, 045114 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi M. et al. Revisiting the valence-band and core-level photoemission spectra of NiO. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 206401 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Veenendaal M. A. Competition between screening channels in core-level x-ray photoemission as a probe of changes in the ground-state properties of transition-metal compounds. Phys. Rev. B 74, 085118 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Okabayashi J. et al. Core-level photoemission study of Ga1−xMnxAs. Phys. Rev. B 58, R4211 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Okabayashi J. et al. Mn 3d partial density of states in Ga1−xMnxAs studied by resonant photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 59, R2486 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Rader O. et al. Resonant photoemission of Ga 1−xMnxAs at the Mn L edge. Phys. Rev. B 69, 075202 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds K. W. et al. Surface effects in Mn L3,2 x-ray absorption spectra from (Ga,Mn)As. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 4065 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi M. et al. Bulk screening in core-level photoemission from Mott-Hubbard and charge-transfer systems. Phys. Rev. B 71, 155102 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Tougaard S. Formalism for quantitative surface analysis by electron spectroscopy. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 8, 2197 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Huijben M. et al. Critical thickness and orbital ordering in ultrathin La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 films. Phys. Rev. B 78, 094413 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Kourkoutis L. F., Song J. H., Hwang H. Y. & Muller D. A. Microscopic origins for stabilizing room-temperature ferromagnetism in ultrathin manganite layers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 11682–11685 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verna A. et al. Measuring magnetic profiles at manganite surfaces with monolayer resolution. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 322, 1212 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Liao Z. et al. Origin of the metal-insulator transition in ultrathin films of La2/3Sr1/3MnO3. Phys. Rev. B 92, 125123 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. et al. Insulating phase at low temperature in ultrathin La0.8Sr0.2MnO3 films. Sci. Rep. 6, 22382 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesquera D. et al. Surface symmetry breaking and strain effects on orbital occupancy in transition metal perovskite epitaxial films. Nat. Commun. 3, 1189 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Laan G. Zen and the art of dichroic photoemission. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenomen 200, 143–159 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds K. W. et al. Magnetic linear dichroism in the angular dependence of core-level photoemission from (Ga,Mn)As using hard X rays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 197601 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda S. et al. Mn 2p core-level spectra of La1−xBaxMnO3 thin films using hard x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy: relation between electronic and magnetic states. Phys. Rev. B 80, 092402 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Bertacco R. et al. Surface electronic and magnetic properties of La2/3Sr1/3MnO3 thin films with extended metallicity above the Curie temperature. Phys. Rev. B 78, 035448 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Brey L. Electronic phase separation in manganite-insulator interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 75, 104423 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Boschker H. et al. High-temperature magnetic insulating phase in ultrathin La0.67Sr0.33MnO3 films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 157207 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertinshaw J. et al. Element-specific depth profile of magnetism and stoichiometry at the La0.67Sr0.33MnO3 /BiFeO3 interface. Phys. Rev. B 90, 041113 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Cowan R. D. Theoretical calculation of atomic spectra using digital computers. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 58, 808 (1968). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.