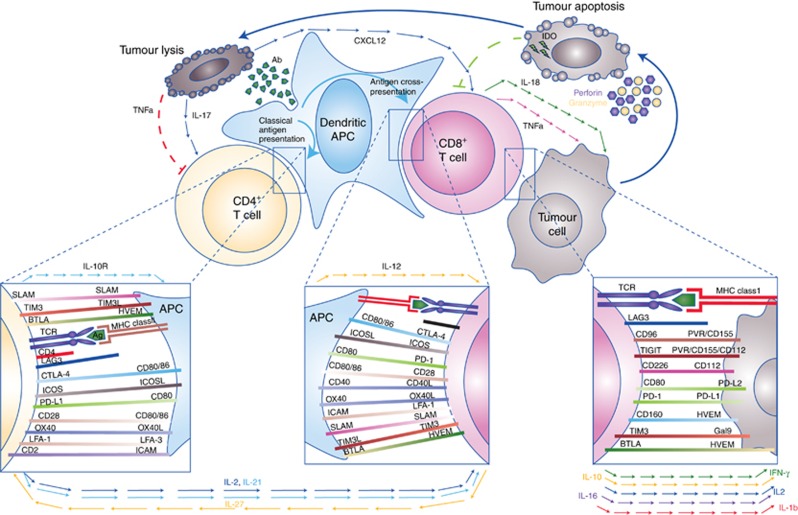

Figure 1.

The cellular immune response to cancer is complex and involves a diverse repertoire of immunoregulatory interactions principally involving antigen presenting cells (APC), T cells, and tumour cells. Presentation of distinct antigen epitopes to CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in the context of major histocompatibility complex class I (on APC or tumour cells directly) and class II (on APCs), respectively, facilitates tumour cell recognition, but numerous other molecular interactions (inset boxes) and input from paracrine and humoral factors (cytokines/chemokines, shown with arrowed lines) integrate to determine the ultimate outcome of immune recognition. Elaboration of survival and inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-2 and IFN-γ, can promote a cytotoxic (CD8+) T-cell response with consequent tumour-directed lytic activity mediated by release of cytotoxic granule contents (e.g., perforin and granyzme) as well as triggering of apoptotic pathways by tumouricidal cytokines (e.g., TNF-α and IFN-γ) and death receptor ligation (e.g., FAS:FAS-L). Debris released from apoptotic/necrotic tumour cells may be taken up by APC and presented in a cycle of immunogenic cell death. However, prolonged immune activation is adaptively opposed by upregulation of immunoinhibitory molecules (e.g., CTLA-4, PD-1, TIM3, TIGIT, and CTLA-4), or their ligands, many of which may be subverted by tumour cells in order to escape immune attack. Release of anti-inflammatory, immunoregulatory or Th2-skewed cytokines also contributes to dampening of the cellular response.