Abstract

Context

Achieving adequate response rates from family members of critically ill patients can be challenging, especially when assessing psychological symptoms.

Objectives

To identify factors associated with completion of surveys about psychological symptoms among family members of critically ill patients.

Methods

Using data from a randomized trial of an intervention to improve communication between clinicians and families of critically ill patients, we examined patient- and family-level predictors of the return of usable surveys at baseline, 3- and 6-months (N=181, 171, and 155, respectively). Family-level predictors included baseline symptoms of psychological distress, decisional independence preference, and attachment style. We hypothesized that family with fewer symptoms of psychological distress, a preference for less decisional independence, and secure attachment style would be more likely to return questionnaires.

Results

We identified several predictors of the return of usable questionnaires. Better self-assessed family-member health status was associated with a higher likelihood, and stronger agreement with a support-seeking attachment style with a lower likelihood, of obtaining usable baseline surveys. At 3 months, family-level predictors of return of usable surveys included having usable baseline surveys, status as the patient’s legal next-of-kin, and stronger agreement with a secure attachment style. The only predictor of receipt of surveys at 6 months was the presence of usable surveys at 3 months.

Conclusion

We identified several predictors of the receipt of surveys assessing psychological symptoms in family of critically ill patients, including family member health status and attachment style. Using these characteristics to inform follow-up mailings and reminders may enhance response rates.

Keywords: Response rate, Non-response bias, Psychological distress, Family member, Critical illness, Family-centered

INTRODUCTION

In order to advance the practice of patient- and family-centered care, research focused on outcomes important to patients and family members is imperative (1–3). In the critical care setting, outcomes related to physiology and survival often occupy a prominent role in clinical research. Although these measures are important, they do not necessarily provide insights into the experiences of critically ill patients and their family members. Measures of quality of life, psychological distress, and communication between clinicians, patients, and family members provide information that more traditional clinical outcomes cannot (4, 5). However, these key outcomes often present unique challenges to investigators. Unlike data abstracted from the medical record, many patient- and family-centered outcomes are measured using questionnaires. Survey response rates among critically ill patients and their family members often fall below 80% (6), and in many cases are below 65% (7–10). An inability to obtain adequate response rates for key outcome measures poses a number of significant threats to research focused on improving the care provided to seriously ill patients and their family members. Low response rates can hinder efforts to identify clinically meaningful differences in patient- and family-centered outcomes and may also be associated with non-response bias when respondents differ from non-respondents in significant ways.

Poor health status and symptoms of psychological distress have been identified as predictors of non-response and attrition in a variety of patient populations (11–15), but less information is available about factors associated with study participation by family members of critically ill patients (16). Using data from a randomized trial of an intervention to improve communication between clinicians and families of critically ill patients (17), we examined patient- and family-level predictors of the return of usable study questionnaires from family members at baseline as well as at 3- and 6-month follow-up assessments. Based on existing evidence about predictors of non-response and attrition (11–15, 18, 19), we chose to assess family member symptoms of psychological distress, decisional independence preference, and attachment style as predictors of return of usable surveys. We hypothesized that family members with fewer symptoms of psychological distress, a preference for less decisional independence (reflecting more trust in clinicians), and secure attachment style would be more likely to return usable questionnaires at the specified time points.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

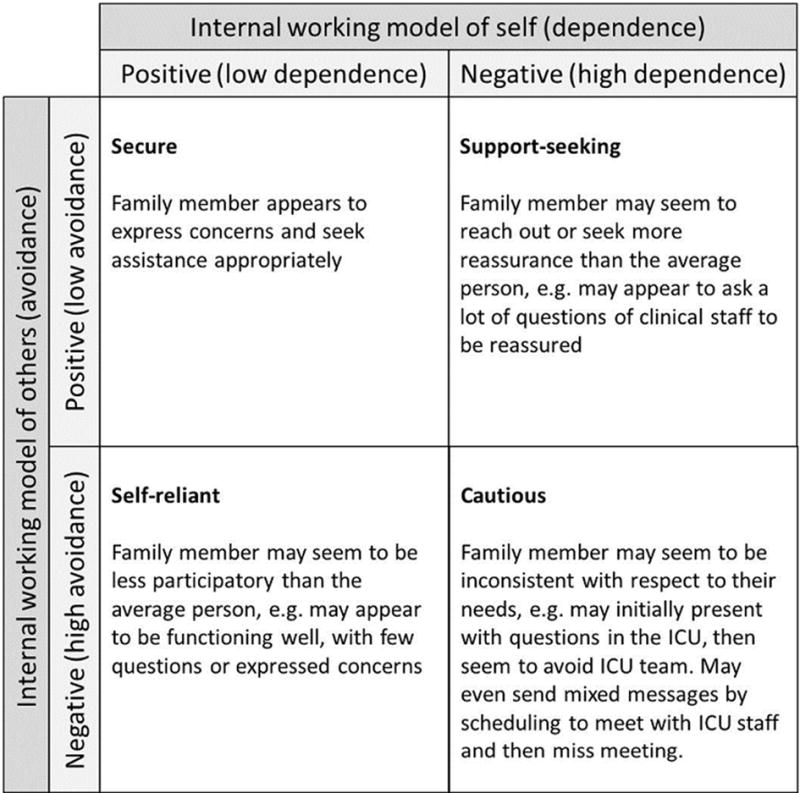

Study Design: Data for this study were drawn from a parallel-group randomized trial of an intervention to improve communication between clinicians and families of critically ill patients during an ICU stay (17). The intervention consisted of a “communication facilitator” who addressed family and team communication needs, using communication tools tailored to support a family member’s attachment styles. Evoked in stressful situations, attachment styles determine an individual’s attitude for engaging others around emotionally-laden issues. These attachment styles include: a secure style, and three insecure styles known as self-reliant, support-seeking, and cautious (20–23) (Figure 1). The intervention’s effect was assessed with family self-report questionnaires distributed in-person at enrollment and with follow-up questionnaires mailed 3 and 6 months after enrollment.

Figure 1.

Attachment Styles and Examples of Family Behavior in the ICU

Participants

Participants were identified by daily screening of the ICU census in two hospitals, an academic level-1 trauma center and a community-based hospital. Eligible patients met the following criteria: 1) in the ICU for >24 hours; 2) age >18 years; 3) mechanically ventilated at enrollment; 4) Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score >6 or diagnostic criteria predicting a >30% risk of hospital mortality (24, 25); 5) legal surrogate decision-maker to consent for patient participation; and 6) a family member able to come to the hospital. Eligibility criteria for family members included: 1) age >18 years; and 2) able to complete the consent process and questionnaires in English. IRB approval was obtained from both sites.

Outcomes

Our outcome was receipt of a usable survey for each assessment point. Baseline surveys were deemed usable if they were completed within 14 days of distribution; follow-up surveys, within 60 days of distribution. This included 181 usable baseline surveys, 171 usable 3-month surveys, and 155 usable 6-month surveys.

Predictor Variables

Patient and family characteristics were considered potential predictors at all three assessment points. Patient characteristics were obtained through medical record review and included patient age, sex, SOFA score at enrollment, hospital site, and randomization status (control or intervention group). Family member demographics were drawn from any available questionnaire (baseline, 3-month, or 6-month) and included the family member’s age, sex, race/ethnicity (white non-Hispanic vs. minority), level of education, legal-next-of-kin status, years of acquaintance with the patient, and relationship to the patient (dummy indicators for spouse, parent, or child). Additional family member predictors from baseline questionnaires included: self-assessed general health status (the first item from the MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey, using 5 response options, recoded for these analysis using a range of 0=”poor” through 2=”good” to 4=”excellent”) (26); any lifetime experience with “extremely upsetting” events (27); whether the family member had discussed end-of-life treatment preferences with the patient; symptoms of depression (the standard Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ]-9 score (28–30)); symptoms of anxiety (the standard Generalized Anxiety Disorder [GAD]-7 score (31, 32)); trust in physicians and trust in nurses (two 5-item scales, each ranging from 0= “strong distrust” to 20= “strong trust”) (33, 34); decisional independence preference (responses ranged from 0=”leave all treatment decisions to the doctor” to 4=”make all treatment decisions on my own”) (35–39); and the extent to which the respondent perceived that each of four different attachment styles applied to them (responses ranged from 0=”not at all like me” to 4=”very much like me”) (20, 40–42). Finally, length of hospital stay and mortality status at hospital discharge were used to predict return of questionnaires at 3 and 6 months, and receipt of a usable questionnaire at the prior assessment point(s) was used to predict receipt of questionnaires at the two follow-up points.

Data Analysis

We used clustered probit regression with a weighted least squares means and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator, theta parameterization, and full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) to identify associations between our predictors and outcomes. First, for each assessment point considered separately, an initial model included all patient and family predictors, and non-significant predictors were removed sequentially in order of decreasing p-value until only the predictors with p<0.05 remained. This procedure produced three time-specific models with a total of 266 family members contributing data. We then employed a structural equation model in which all three time points were entered simultaneously, again using FIML and a WLSMV estimator. In this combined model, several of the statistically significant predictors from the three time-specific models dropped to non-significance and were removed. In an effort to further evaluate potential effects of the communication intervention on the receipt of usable surveys, we tested the final model with the control sample alone and obtained results similar to those based on the full sample. In addition, using the control sample, we repeated the steps used for the full sample, in order to locate all of the significant independent predictors of questionnaire return at the three assessment points. However, due to the small size of the control sample, some predictors could not be adequately tested. Because the full sample made more complete use of our data with a more robust sample size, we report only the results from the full sample here. Regression analyses and path models were produced with Mplus Version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA). IBM SPSS Statistics Release 19.0.0 (Somers, NY) was used to construct descriptive tables. Statistical significance for all hypothesis tests was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Family members (n=269) provided 181 usable baseline questionnaires, 171 usable 3-month questionnaires, and 155 usable 6-month questionnaires; data were available for 168 patients. The majority of family members were women (71%) whereas most of the patients were men (64%). Most family members identified as the patient’s legal next of kin (62%), having known the patient for an average of 33 years (SD 15.6). Family members reported a high level of trust in both nurses and physicians, and 41% wanted to share responsibility for decision-making equally between themselves and the medical staff while 32% wanted decisions made by the doctor. When identification with an attachment style was based on endorsement of one of the two top response options for the item defining the style, 45% of family members identified as secure, 23% as self-reliant, 12% as cautious, and 5% as support-seeking (Table 1). Patient characteristics are provided in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Family Members

| Characteristic | Valid n | Statistic |

|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 269 | 190 (70.6) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 226 | 50.8 (13.1) |

| Racial/ethnic minority, n (%) | 231 | 42 (18.2) |

| Education Level, n (%) | 231 | |

| 8th grade or less | 2 (0.9) | |

| Some high school | 6 (2.6) | |

| Diploma or equivalent | 44 (19.0) | |

| Trade school or some college | 88 (38.1) | |

| Undergraduate degree | 54 (23.4) | |

| Post-college study | 37 (16.0) | |

| Legal next of kin, n (%) | 266 | 166 (62.4) |

| Relationship to patient, n (%) | 269 | |

| Spouse/partner | 78 (29.0) | |

| Child | 74 (27.5) | |

| Parent | 52 (19.3) | |

| Other | 65 (24.2) | |

| Years of acquaintance with patient | 227 | 33.0 (15.6) |

| Trust in physicians, mean (SD) | 186 | 17.1 (3.3) |

| Trust in nurses, mean (SD) | 192 | 17.3 (3.3) |

| Baseline PHQ9 score, mean (SD) | 186 | 6.2 (5.7) |

| Baseline GAD7 score, mean (SD) | 186 | 5.9 (5.3) |

| Decisional independence, n (%) | 186 | |

| Prefer all decisions by doctor | 14 (07.5) | |

| Final decision by doctor, family member’s opinion considered | 49 (26.3) | |

| Equally shared responsibility | 76 (40.9) | |

| Final decision by family member, doctor’s opinion considered | 47 (25.3) | |

| Prefer all decisions by family member | 0 (00.0) | |

| Ever discussed end-of-life treatment preference with patient, n (%) | 187 | 108 (57.8) |

| Baseline health status, n (%) | 192 | |

| Poor | 6 (03.1) | |

| Fair | 12 (06.3) | |

| Good | 46 (24.0) | |

| Very good | 92 (47.9) | |

| Excellent | 36 (18.8) | |

| Ever experienced traumatic event, n (%) | 191 | 153 (80.1) |

| Secure attachment style, n (%) | 186 | |

| Not at all like me | 20 (10.8) | |

| … | 22 (11.8) | |

| Somewhat like me | 60 (32.3) | |

| … | 36 (19.4) | |

| Very much like me | 48 (25.8) | |

| Cautious attachment style, n (%) | 189 | |

| Not at all like me | 104 (55.0) | |

| … | 33 (17.5) | |

| Somewhat like me | 29 (15.3) | |

| … | 16 (08.5) | |

| Very much like me | 7 (03.7) | |

| Support-seeking attachment style, n (%) | 188 | |

| Not at all like me | 118 (62.8) | |

| … | 35 (18.6) | |

| Somewhat like me | 25 (13.3) | |

| … | 7 (03.7) | |

| Very much like me | 3 (01.6) | |

| Self-reliant attachment style, n (%) | 189 | |

| Not at all like me | 41 (21.7) | |

| … | 46 (24.3) | |

| Somewhat like me | 59 (31.2) | |

| … | 31 (16.4) | |

| Very much like me | 12 (06.3) | |

| Provided usable responses at baseline, n (%) | 269 | 181 (67.3) |

| Provided usable responses at 3-month follow-up, n (%) | 269 | 171 (63.6) |

| Provided usable responses at 6-month follow-up, n (%) | 269 | 155 (57.6) |

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients

| Characteristic | Valid n | Statistic |

|---|---|---|

| Randomized to intervention group | 168 | 82 (48.8) |

| Female, n(%) | 168 | 60 (35.7) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 168 | 53.8 (18.1) |

| Racial/ethnic minority, n(%) | 152 | 28 (18.4) |

| DNR in place at time of ICU admit, n(%) | 153 | 3 (2.0) |

| SOFA score at ICU admit | 164 | 9.9 (3.2) |

| Charlson score at ICU admit | 153 | 2.2 (2.1) |

| Length of hospital stay | 153 | 28.5 (24.3) |

| Length of ICU stay | 168 | 19.4 (20.3) |

| Died in ICU | 168 | 46 (27.4) |

| Died in hospital | 168 | 51 (30.4) |

| Community hospital site | 168 | 12 (7.1) |

Predictors of Return of Usable Data by Family Members

Both direct and indirect effects were identified for several predictors. The direct effect of each exogenous predictor represents the portion of the exposure effect not mediated by other predictors, whereas the indirect effect is the portion of the exposure effect that is exerted through other, mediating, variables. In a structural equation model with all three time points (baseline, 3-month, and 6-month) entered simultaneously, several of the exogenous predictors explained significant amounts of variation in the presence of usable surveys (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Predictors of Provision of Usable Data by Family Members, Three Assessment Points

MODEL FIT: χ2=12.150, 18 df, p=0.8394

The following predictors had direct effects on the receipt of usable baseline surveys: randomization status, self-assessed health status, and support-seeking attachment style. Family members of patients in the intervention group were more likely to provide usable baseline data as were family members with better self-assessed health status. Stronger agreement with the support-seeking attachment style was associated with a lower likelihood of having a usable baseline questionnaire. Predictors with positive direct effects on the receipt of usable surveys at 3 months included usable surveys at baseline, status as the patient’s legal next-of-kin, and stronger agreement with the secure attachment style. The only predictor with a direct effect at 6 months was the presence of usable surveys at 3 months (Table 3).

Table 3.

Direct and Indirect Effects of Predictors on Provision of Usable Data by Family Members

| Outcome | Predictor | b | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Data | Randomized to Intervention Group | 0.558 | 0.012 | 0.125, 0.990 |

| Self-Assessed Health Status | 0.181 | 0.026 | 0.021, 0.340 | |

| Extent Support -Seeking Attachment Style | −0.220 | 0.003 | −0.363, −0.076 | |

| 3-Month Data | Usable Data at Baseline | 0.504 | 0.000 | 0.262, 0.747 |

| Legal Next of Kin | 0.369 | 0.032 | 0.032, 0.706 | |

| Extent Secure Attachment Style | 0.224 | 0.014 | 0.045, 0.403 | |

| Iendirect:Effects | ||||

| Randomized to Intervention Group | 0.281 | 0.028 | 0.031, 0.532 | |

| Self-Assessed Health Status | 0.091 | 0.031 | 0.008, 0.174 | |

| Extent Support-Seeking Attachment Style | −0.111 | 0.005 | −0.187, −0.034 | |

| 6-Month Data | Usable Data at 3 Months | 1.573 | 0.000 | 0.958, 2.189 |

| Iendirect: Effects | ||||

| Randomized to Intervention Group | 0.443 | 0.033 | 0.035, 0.850 | |

| Self-Assessed Health Status | 0.143 | 0.037 | 0.009, 0.278 | |

| Usable Data at Baseline | 0.794 | 0.000 | 0.405, 1.183 | |

| Extent Support-Seeking Attachment Style | −0.174 | 0.010 | −0.307, −0.041 | |

| Legal Next of Kin | 0.580 | 0.051 | −0.001, 1.162 | |

| Extent Secure Attachment Style | 0.352 | 0.016 | 0.064, 0.641 |

Indirect effects for several predictors were observed for the 3-month and 6-month assessments. Randomization status and baseline health status both exerted positive indirect effects on usable data at 3 and 6 months through associations with receipt of a usable baseline questionnaire. Stronger agreement with the support-seeking attachment style exerted a negative indirect effect at 3 and 6 months through its association with usable baseline data. Additional positive indirect effects at 6 months were observed for usable baseline data, and stronger agreement with secure attachment style (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Improving response rates is challenging, and limited evidence exists to support specific practices to maximize response rates in the health care setting (43). Repeat mailings or telephone contact may be employed to enhance receipt of surveys from study participants, but these methods are not always effective (43). In addition to concerns about response rate, non-response bias can also be an issue when utilizing family-centered outcomes derived from questionnaires (16, 44). An improved understanding of factors associated with participant completion of study surveys may facilitate the use of novel strategies to enhance response rates and address non-response bias. Using data from a randomized trial of an intervention to improve communication between clinicians and families of critically ill patients, we examined surveys focused on symptoms of psychological distress and identified several predictors with direct effects on the return of usable surveys. Our findings have implications for study design and implementation, particularly for scientists using family-centered outcomes in the critical care setting. In particular, we were able to identify individuals at high risk for non-response; researchers may target these individuals with focused strategies to accommodate and overcome identified risk factors and avoid using resources with individuals who are likely to respond without additional support.

In our sample, randomization to the control group was a significant predictor of non-response at baseline, suggesting that increased attention to the family of patients randomized to the control group may be important to enhance questionnaire return. At 3 and 6 months, family-level predictors of return of usable surveys included having a usable survey at baseline, suggesting the initial survey response may serve as an important marker for better long-term follow up. Failure to return a baseline survey could prompt additional follow-up in order to obtain future surveys. We also found that a family member’s status as legal next of kin was associated with the return usable surveys at 3-months. For studies seeking response from family members of critically ill patients, the family member’s relationship with the patient may also be an important predictor of response. Health status has been identified as a predictor of survey response in other study populations (12, 15, 45), and here, better self-assessed health among family members was associated with completion of baseline surveys. This identifies family members with health limitations as participants who may require intensive follow-up to facilitate survey return.

Attachment style was also a predictor of survey return. Evoked under stressful circumstances, such as serious illness or hospitalization, attachment styles are schemas or “filters” that determine an individual’s propensity for engaging others around emotionally-laden issues. There are 4 adult attachment styles, one secure and three insecure styles: self-reliant (also sometimes called dismissing), support-seeking (preoccupied), and cautious (fearful) (20). The three insecure attachment styles pertain to about 45% of the population (46). Prior research has shown that, among patients with diabetes, insecure attachment style is associated with lower satisfaction with care and lower perceived quality of physician communication (21). In our study, identification with a support-seeking attachment style was associated with a lower likelihood of obtaining usable baseline surveys whereas identification with a secure attachment style was associated with higher likelihood of 3-month survey return. Importantly, insecure attachment styles have been associated with mental health disorders as well as mental health utilization (47–50), and non-response from individuals with insecure attachment styles may signal poor follow-up from a population of participants with symptoms of anxiety, depression, or posttraumatic stress. Our surveys focused on symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress, potentially increasing the probability of identifying attachment style as a predictor of return of usable surveys. It is possible that, in addition to being a predictor of family member response to critical illness of a loved one, family member attachment style may also help guide strategies to ensure adequate response rates in studies using key family-centered outcomes like symptoms of psychological distress. As an example, individuals with a support-seeking style may be more likely to benefit from a “human touch” or “personal touch” when being administered a questionnaire, as compared to other attachment styles.

Finally, predictors of non-response may also be utilized to project accrual of outcome data after study enrollment begins. Calculation of a sample size needed to demonstrate a desired effect size is an essential component of trial design. However, low response rates on study questionnaires may reduce the number of participants with usable data. This can hinder efforts to identify clinically meaningful differences in patient- and family-centered outcomes. As seen in our sample, receipt of usable surveys at baseline was a significant predictor of participant response at both 3- and 6-month assessments. For investigators, early recognition that a large number of participants are less likely to complete follow-up surveys may serve as an early warning that an effective sample size may not be achieved. This information could be used to trigger the application of contingency strategies designed to improve retention or recruitment or could allow planning for a longer enrollment period.

This study has several important limitations. First, the definition of usable surveys may have excluded participants who did respond, but not within the specified time frames. However, the time frames used to determine usability were employed to ensure that study outcomes truly reflected baseline, 3-month, and 6-month assessments. Second, we are unable to determine reasons for failure to return usable surveys, making it impossible to know if family members chose not to respond, as opposed to family members who did not actually receive the mailed surveys. Third, this study occurred in a single geographic region, using surveys directed to family members of critically ill patients. Thus, our results may not be generalizable to other regions or different populations. Finally, data for this study were drawn from a randomized trial of an intervention to improve communication between clinicians and families of critically ill patients during an ICU stay. Being randomized to the intervention condition had a strong effect on return of usable baseline questionnaires, and return of those questionnaires had a similarly strong effect on the return of subsequent questionnaires. This raises the concern that our model may have excluded variables that could be important predictors of engagement in research activities in situations where the anticipation and receipt of a desired intervention are not motivating factors. To investigate this question, we repeated the steps used for the full sample, using just the participants who were randomized to the control condition. However, because of the small size of the control group, some predictors could not be adequately tested. Given this limitation, we encourage additional research assessing factors influencing the participation of family caregivers in questionnaire-based studies in order to expand upon our findings and improve the ability to capture essential family-centered outcomes.

In conclusion, we identified several predictors of the receipt of usable surveys assessing psychological symptoms in family members of critically ill patients. These include readily measurable family member characteristics, including health status and attachment style. Using these characteristics to direct follow-up mailings and telephone reminders may enhance response rates and provide a mechanism to improve receipt of input from potentially under-represented populations. Furthermore, early recognition of impending issues with receipt of outcome data may allow rapid institution of contingency plans to achieve study goals.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by R01NR05226 from the National Institute of Nursing Research. Dr. Long was supported in part by a Junior Faculty Career Development Award from the National Palliative Care Research Center (NPCRC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Snyder CF, Jensen RE, Segal JB, et al. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs): putting the patient perspective in patient-centered outcomes research. Medical care. 2013;51(8 Suppl 3):S73–79. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829b1d84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV. The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;312(15):1513–1514. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank L, Forsythe L, Ellis L, et al. Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2015;24(5):1033–1041. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0893-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curtis JR. The “patient-centered” outcomes of critical care: what are they and how should they be used? New horizons (Baltimore, Md) 1998;6(1):26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cabrini L, Landoni G, Antonelli M, et al. Critical care in the near future: patient-centered, beyond space and time boundaries. Minerva anestesiologica. 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oeyen SG, Vandijck DM, Benoit DD, et al. Quality of life after intensive care: a systematic review of the literature. Critical care medicine. 2010;38(12):2386–2400. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f3dec5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kodali S, Stametz RA, Bengier AC, et al. Family experience with intensive care unit care: association of self-reported family conferences and family satisfaction. Journal of critical care. 2014;29(4):641–644. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang DY, Yagoda D, Perrey HM, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms among families of adult intensive care unit survivors immediately following brief length of stay. Journal of critical care. 2014;29(2):278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinoshita S, Miyashita M. Evaluation of end-of-life cancer care in the ICU: perceptions of the bereaved family in Japan. The American journal of hospice & palliative care. 2013;30(3):225–230. doi: 10.1177/1049909112446805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jongerden IP, Slooter AJ, Peelen LM, et al. Effect of intensive care environment on family and patient satisfaction: a before-after study. Intensive care medicine. 2013;39(9):1626–1634. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2966-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matthews FE, Chatfield M, Freeman C, et al. Attrition and bias in the MRC cognitive function and ageing study: an epidemiological investigation. BMC public health. 2004;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nummela O, Sulander T, Helakorpi S, et al. Register-based data indicated nonparticipation bias in a health study among aging people. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1418–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Volken T. Second-stage non-response in the Swiss health survey: determinants and bias in outcomes. BMC public health. 2013;13:167. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damen NL, Versteeg H, Serruys PW, et al. Cardiac patients who completed a longitudinal psychosocial study had a different clinical and psychosocial baseline profile than patients who dropped out prematurely. European journal of preventive cardiology. 2015;22(2):196–199. doi: 10.1177/2047487313506548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan JP, Li N, Cui B, et al. Characteristics of participants’ and caregivers’ influence on non-response in a cross-sectional study of dementia in an older population. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics. 2016;62:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Shannon SE, et al. Potential for response bias in family surveys about end-of-life care in the ICU. Chest. 2009;136(6):1496–1502. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, et al. Randomized Trial of Communication Facilitators to Reduce Family Distress and Intensity of End-of-Life Care. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2016;193(2):154–162. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0900OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Multone E, Vader JP, Mottet C, et al. Characteristics of non-responders to self-reported questionnaires in a large inflammatory bowel disease cohort study. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2015;50(11):1348–1356. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2015.1041150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Littman AJ, Boyko EJ, Jacobson IG, et al. Assessing nonresponse bias at follow-up in a large prospective cohort of relatively young and mobile military service members. BMC medical research methodology. 2010;10:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1991;61(2):226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Katon W, et al. Influence of patient attachment style on self-care and outcomes in diabetes. Psychosomatic medicine. 2004;66(5):720–728. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000138125.59122.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciechanowski PS, Worley LL, Russo JE, et al. Using relationship styles based on attachment theory to improve understanding of specialty choice in medicine. BMC medical education. 2006;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ciechanowski PS. Working with interpersonal styles in the patient-provider relationship. In: Anderson BJRR, editor. Practical Psychology for Diabetes Clinicians. Alexandria Virginia: American Diabetes Association; 2002. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peres Bota D, Melot C, Lopes Ferreira F, et al. The Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score (MODS) versus the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score in outcome prediction. Intensive care medicine. 2002;28(11):1619–1624. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kajdacsy-Balla Amaral AC, Andrade FM, Moreno R, et al. Use of the sequential organ failure assessment score as a severity score. Intensive care medicine. 2005;31(2):243–249. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2528-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elhai JD, Franklin CL, Gray MJ. The SCID PTSD module’s trauma screen: validity with two samples in detecting trauma history. Depression and anxiety. 2008;25(9):737–741. doi: 10.1002/da.20318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, et al. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. General hospital psychiatry. 2006;28(1):71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, et al. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Medical care. 2004;42(12):1194–1201. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowe B, Spitzer RL, Grafe K, et al. Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians’ diagnoses. Journal of affective disorders. 2004;78(2):131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of internal medicine. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dear BF, Titov N, Sunderland M, et al. Psychometric comparison of the generalized anxiety disorder scale-7 and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire for measuring response during treatment of generalised anxiety disorder. Cognitive behaviour therapy. 2011;40(3):216–227. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.582138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall MA, Zheng B, Dugan E, et al. Measuring patients’ trust in their primary care providers. Medical care research and review: MCRR. 2002;59(3):293–318. doi: 10.1177/1077558702059003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dugan E, Trachtenberg F, Hall MA. Development of abbreviated measures to assess patient trust in a physician, a health insurer, and the medical profession. BMC health services research. 2005;5:64. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, et al. Decision-making in the ICU: perspectives of the substitute decision-maker. Intensive care medicine. 2003;29(1):75–82. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1569-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heyland DK, Tranmer J, O’Callaghan CJ, et al. The seriously ill hospitalized patient: preferred role in end-of-life decision making? Journal of critical care. 2003;18(1):3–10. doi: 10.1053/jcrc.2003.YJCRC2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson SK, Bautista CA, Hong SY, et al. An empirical study of surrogates’ preferred level of control over value-laden life support decisions in intensive care units. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011;183(7):915–921. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201008-1214OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, et al. Posttraumatic stress and complicated grief in family members of patients in the intensive care unit. Journal of general internal medicine. 2008;23(11):1871–1876. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0770-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P. The Control Preferences Scale. The Canadian journal of nursing research = Revue canadienne de recherche en sciences infirmieres. 1997;29(3):21–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ciechanowski P, Katon WJ. The interpersonal experience of health care through the eyes of patients with diabetes. Social science & medicine (1982) 2006;63(12):3067–3079. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ciechanowski PS, Russo JE, Katon WJ, et al. The association of patient relationship style and outcomes in collaborative care treatment for depression in patients with diabetes. Medical care. 2006;44(3):283–291. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000199695.03840.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Griffin DW, Bartholomew K. The metaphysics of measurement: The case of adult attachment. In: Perlman KBD, editor. Attachment processes in adulthood. London, England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1994. pp. 17–52. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakash RA, Hutton JL, Jørstad-Stein EC, et al. Maximising response to postal questionnaires – A systematic review of randomised trials in health research. BMC medical research methodology. 2006;6:5–5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oldenkamp M, Wittek RP, Hagedoorn M, et al. Survey nonresponse among informal caregivers: effects on the presence and magnitude of associations with caregiver burden and satisfaction. BMC public health. 2016;16(1):480. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2948-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoeymans N, Feskens EJ, Van Den Bos GA, et al. Non-response bias in a study of cardiovascular diseases, functional status and self-rated health among elderly men. Age and ageing. 1998;27(1):35–40. doi: 10.1093/ageing/27.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mickelson KD, Kessler RC, Shaver PR. Adult attachment in a nationally representative sample. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1997;73(5):1092–1106. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meng X, D’Arcy C, Adams GC. Associations between adult attachment style and mental health care utilization: Findings from a large-scale national survey. Psychiatry research. 2015;229(1–2):454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palitsky D, Mota N, Afifi TO, et al. The association between adult attachment style, mental disorders, and suicidality: findings from a population-based study. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 2013;201(7):579–586. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31829829ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woodhouse S, Ayers S, Field AP. The relationship between adult attachment style and post-traumatic stress symptoms: A meta-analysis. Journal of anxiety disorders. 2015;35:103–117. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hooper LM, Tomek S, Roter D, et al. Depression, patient characteristics, and attachment style: correlates and mediators of medication treatment adherence in a racially diverse primary care sample. Primary health care research & development. 2016;17(2):184–197. doi: 10.1017/S1463423615000365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]