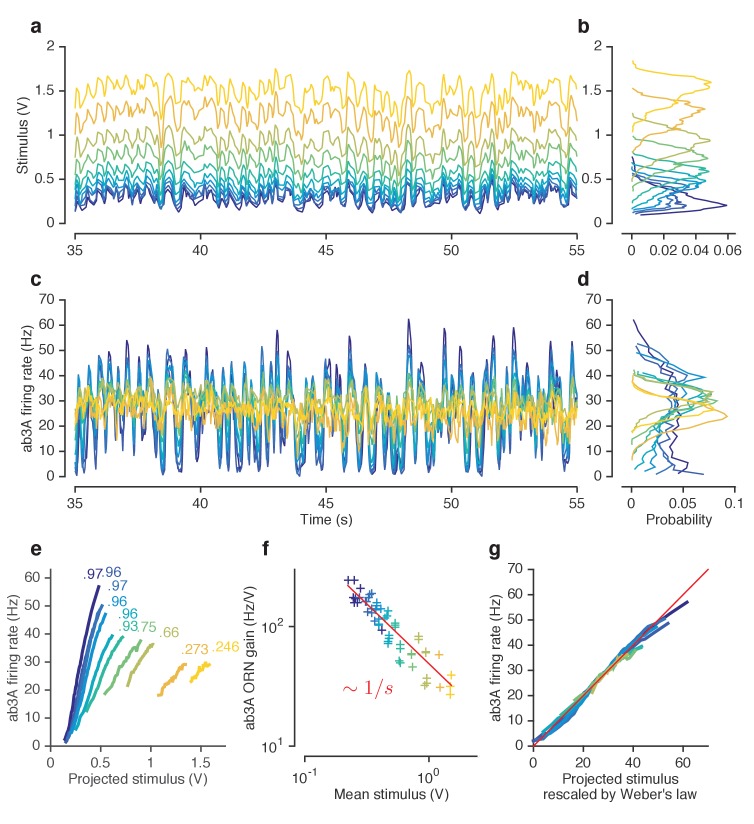

Figure 3. ORNs decrease gain with stimulus mean, consistent with the Weber-Fechner Law.

(a) Ethyl acetate stimuli with different mean intensities but similar variances. Stimulus intensity measured using a Photo-Ionization Detector (PID), units in Volts (V). Colors indicate mean stimulus intensity. (b) Corresponding stimulus distributions. (c) ab3A firing rate responses to these stimuli. (d) Corresponding response distributions. (e) ORN responses vs. stimulus projected through linear filters. Colored numbers indicate between linear projections and ORN response. (f) ORN gain vs. mean stimulus for each trial. Red line is the Weber-Fechner prediction () (g) After rescaling the projected stimulus by the gain predicted by the red curve in (f), and correcting for an offset, ORN responses collapse onto one line. n = 55 trials from 7 ORNs in 3 flies. All plots except (f) show means across all trials. (f) shows individual trials.