ABSTRACT

With the proposal to include Aspergillus PCR in the revised European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) definitions for fungal disease, commercially manufactured assays may be required to provide standardization and accessibility. The PathoNostics AsperGenius assay represents one such test that has the ability to detect a range of Aspergillus species as well as azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Its performance has been validated on bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and serum specimens, but recent evidence suggests that testing of plasma may have enhanced sensitivity over that with serum. We decided to evaluate the analytical and clinical performances of the PathoNostics AsperGenius assay for testing of plasma. For the analytical evaluations, plasma was spiked with various concentrations of Aspergillus genomic DNA before extraction following international recommendations, using two automated platforms. For the clinical study, 211 samples from 10 proven/probable invasive aspergillosis (IA) and 2 possible IA cases and 27 controls were tested. The limits of detection for testing of DNA extracted using the bioMérieux EasyMag and Qiagen EZ1 extractors were 5 and 10 genomes/0.5-ml sample, respectively. In the clinical study, true positivity was significantly greater than false positivity (P < 0.0001). The sensitivity and specificity obtained using a single positive result as significant were 80% and 77.8%, respectively. If multiple samples were required to be positive, specificity was increased to 100%, albeit sensitivity was reduced to 50%. The AsperGenius assay provided good clinical performance, but the predicted improvement of testing with plasma was not seen, possibly as a result of target degradation attributed to sample storage. Prospective testing is required to determine the clinical utility of this assay, particularly for the diagnosis of azole-resistant disease.

KEYWORDS: invasive aspergillosis, Aspergillus PCR, azole resistance determination, azole resistance

INTRODUCTION

Standardization of Aspergillus PCR testing of blood-based samples has led to the proposal to include Aspergillus PCR in the second revision of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) consensus definitions for invasive fungal disease (IFD) (1–4). This may increase demand for Aspergillus PCR, as it can be used, in combination with other biomarker assays (galactomannan enzyme immunoassay [EIA] and β-d-glucan assay), to improve the management of patients at risk of invasive aspergillosis (IA) (5). Easily attainable, quality-controlled, and well-validated assays are necessary, and commercially developed assays help in achieving these requirements.

Several commercial Aspergillus PCR assays have been developed (MycAssay Aspergillus, Renishaw Fungiplex, Ademtech MycoGENIE, and PathoNostics AsperGenius assays), with various degrees of clinical validation (6–10). Of particular interest given the emergence of azole-resistant strains of Aspergillus fumigatus are the Ademtech MycoGENIE and PathoNostics AsperGenius assays, which have the ability to detect the major single nucleotide polymorphisms that imply environmentally driven resistance. Tests to detect genetic mechanisms of azole resistance have been applied directly to clinical samples and have the potential to overcome the limited sensitivity of conventional culture techniques (7, 8). The application of these tests to noninvasive sample types (e.g., blood) will improve their clinical utility, and some success has been noted for testing of serum (7).

Recently, the European Aspergillus PCR Initiative (EAPCRI) showed that both the analytical and clinical performances of Aspergillus PCR were superior for testing with plasma over those for testing with serum (3, 4). It was proposed that use of plasma avoided DNA trapping during clot formation and that, subsequently, the available target was greater and the test performance enhanced. In the previous evaluation of the PathoNostics AsperGenius assay for testing with serum, the sensitivity and specificity were 79% and 91%, respectively, and genetic screening for resistance direct from the sample was obtained in 50% of cases (7). It was hypothesized that testing of plasma may improve the performance of the AsperGenius assay. Nevertheless, validation of testing with plasma is required to enhance the application range and assay robustness.

This article reports the analytical and clinical performances of the PathoNostics AsperGenius assay for testing with plasma samples, using methods in line with international recommendations (4).

RESULTS

Analytical performance of the AsperGenius species assay.

For DNA extraction from plasma by use of a Qiagen EZ1 DSP virus kit, the limits of detection (LOD) for both the A. fumigatus-specific and Aspergillus species assays were 25 genomes/0.5-ml sample with a 5-μl template input and 10 genomes/0.5-ml sample with a 10-μl template input (Table 1). Increasing the amount of DNA template also improved the reproducibility for detection of 5 genomes/0.5-ml sample but did not improve detection of 1 genome/0.5-ml sample.

TABLE 1.

Analytical performance of the PathoNostics AsperGenius species assay for testing of A. fumigatus genomic DNA extracted from plasma samples by use of a Qiagen EZ1 Advance XL instrument

| DNA template vol (μl) | Fungal load (genomes/0.5-ml sample) | PathoNostics AsperGenius target |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A. fumigatus |

Aspergillus spp. |

A. terreus |

Internal control |

|||||

| No. of positive results/total no. of samples | Mean Cq value (SD) | No. of positive results/total no. of samples | Mean Cq value (SD) | No. of positive results/total no. of samples | No. of positive results/total no. of samples | Mean Cq value (SD) | ||

| 5 | 10,000 | 7/7 | 27.21 (0.63) | 7/7 | 26.18 (0.56) | 0/7 | 7/7 | 31.33 (2.02) |

| 1,000 | 7/7 | 30.16 (0.54) | 7/7 | 29.07 (0.37) | 0/7 | 7/7 | 32.57 (2.62) | |

| 500 | 7/7 | 31.37 (0.61) | 7/7 | 30.30 (0.35) | 0/7 | 7/7 | 32.79 (2.26) | |

| 100 | 7/7 | 34.6 (1.55) | 7/7 | 32.60 (0.40) | 0/7 | 7/7 | 33.53 (2.44) | |

| 75 | 9/9 | 34.26 (0.75) | 9/9 | 33.14 (1.23) | 0/9 | 9/9 | 32.65 (2.18) | |

| 50 | 9/9 | 35.47 (1.13) | 9/9 | 34.15 (0.70) | 0/9 | 9/9 | 33.19 (2.72) | |

| 25 | 12/12a | 37.29 (1.40) | 12/12a | 35.41 (1.24) | 0/12a | 12/13a | 33.30 (1.87) | |

| 10 | 11/15 | 37.62 (1.63) | 12/15 | 35.33 (0.80) | 0/15 | 15/15 | 30.67 (3.82) | |

| 5 | 4/15 | 38.94 (1.23) | 5/15 | 36.53 (0.78) | 0/15 | 15/15 | 32.95 (2.41) | |

| 1 | 3/15 | 39.82 (1.29) | 4/15 | 37.14 (0.78) | 0/15 | 15/15 | 32.39 (2.56) | |

| 0 | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 | 15/15 | 30.49 (2.81) | |||

| 10 | 25 | 3/3 | 37.57 (1.22) | 3/3 | 34.60 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 39.14 (1.05) |

| 10 | 10/10 | 38.69 (2.07) | 10/10 | 35.86 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 32.45 (1.79) | |

| 5 | 5/10 | 42.62 (4.23) | 5/10 | 37.66 | 5/10 | 10/10 | 31.73 (2.72) | |

| 1 | 2/10 | 40.40 (1.13) | 2/10 | 36.95 | 2/10 | 10/10 | 32.09 (2.15) | |

| 0 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 5/5 | 38.99 (3.08) | |||

One sample was deemed inhibitory to PCR amplification, and as such, only 12 replicates were included in the analysis of the A. fumigatus, A. terreus, and Aspergillus species assays, whereas results for 12/13 replicates are shown for the corresponding internal control PCR.

Using the bioMérieux EasyMag system for DNA extraction, the LOD with a 5-μl template input for both the A. fumigatus and Aspergillus species assays improved to 5 genomes/0.5-ml sample, compared to the equivalent volume of eluate extracted by use of a Qiagen EZ1 DSP virus kit (Tables 1 and 2). However, 4/31 replicates across all burdens generated low-level false-positive A. terreus results (mean threshold cycle [CT], 42.4). Increasing the template input volume to 10 μl did not improve the 100% LOD, but the reproducibility of detection of 1 genome/0.5-ml sample was improved (for the A. fumigatus assay, 3/5 replicates with 10 μl of template versus 0/5 replicates with 5 μl of template; for the Aspergillus species assay, 3/5 replicates with 10 μl of template versus 1/5 replicates with 5 μl of template).

TABLE 2.

Analytical performance of the PathoNostics AsperGenius species assay for testing of A. fumigatus genomic DNA extracted from plasma samples by use of a bioMérieux EasyMag instrument

| DNA template vol (μl) | Fungal load (genomes/0.5-ml sample) | PathoNostics AsperGenius target |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A. fumigatus |

Aspergillus spp. |

A. terreus |

Internal control |

||||||

| No. of positive results/total no. of samples | Mean Cq value (SD) | No. of positive results/total no. of samples | Mean Cq value (SD) | No. of positive results/total no. of samples | Mean Cq value (SD) | No. of positive results/total no. of samples | Mean Cq value (SD) | ||

| 5 | 10,000 | 1/1 | 24.72 | 1/1 | 23.86 | 1/1 | 41.95 | 1/1 | 29.68 |

| 1,000 | 1/1 | 27.93 | 1/1 | 26.55 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 32.25 | ||

| 500 | 1/1 | 28.85 | 1/1 | 27.23 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 31.67 | ||

| 100 | 1/1 | 31.26 | 1/1 | 29.43 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 32.43 | ||

| 50 | 3/3 | 33.24 (0.98) | 3/3 | 30.75 (0.81) | 1/3 | 39.39 | 3/3 | 33.33 (0.67) | |

| 25 | 3/3 | 34.31 (1.79) | 3/3 | 31.20 (0.61) | 1/3 | 42.10 | 3/3 | 33.57 (0.80) | |

| 10 | 5/5 | 37.5 (1.63) | 5/5 | 32.5 (0.41) | 0/5 | 5/5 | 31.86 (0.61) | ||

| 5 | 5/5 | 38.0 (2.66) | 5/5 | 33.28 (0.73) | 0/5 | 5/5 | 33.27 (0.82) | ||

| 1 | 0/5 | 1/5 | 35.35 | 1/5 | 43.90 | 5/5 | 33.48 (1.00) | ||

| 0 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 5/5 | 31.83 (1.56) | ||||

| 10 | 10 | 1/1 | 35.82 | 1/1 | 34.46 | 0/5 | 1/1 | 33.15 | |

| 5 | 5/5 | 38.65 (1.90) | 5/5 | 35.80 (1.15) | 0/5 | 5/5 | 30.56 (1.00) | ||

| 1 | 3/5 | 40.67 (2.14) | 3/5 | 36.94 (1.45) | 0/5 | 5/5 | 31.59 (1.77) | ||

| 0 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 5/5 | 32.60 (1.25) | ||||

Using the bioMérieux EasyMag system to extract A. terreus DNA from plasma, the LOD for both the A. terreus-specific and Aspergillus species targets was 5 genomes/0.5-ml sample with 5 μl of DNA template; for 1 genome/0.5-ml sample, the reproducibility for both targets was 33.3%. Increasing the input to 10 μl per reaction mixture lowered the LOD to 1 genome/0.5-ml sample (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Analytical performance of the PathoNostics AsperGenius species assay for testing of A. terreus genomic DNA extracted from plasma samples by use of a bioMérieux EasyMag instrument

| DNA template vol (μl) | Fungal load (genomes/0.5-ml sample) | PathoNostics AsperGenius target |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A. fumigatus |

Aspergillus spp. |

A. terreus |

Internal control |

|||||

| No. of positive results/total no. of samples | No. of positive results/total no. of samples | Mean Cq value (SD) | No. of positive results/total no. of samples | Mean Cq value (SD) | No. of positive results/total no. of samples | Mean Cq value (SD) | ||

| 5 | 10,000 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 24.30 | 1/1 | 26.10 | 1/1 | 30.21 |

| 1,000 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 27.40 | 1/1 | 29.14 | 1/1 | 32.49 | |

| 500 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 27.98 | 1/1 | 30.23 | 1/1 | 33.37 | |

| 100 | 0/2 | 2/2 | 30.14 (0.04) | 2/2 | 32.48 (0.05) | 2/2 | 33.82 (0.21) | |

| 75 | 0/2 | 2/2 | 30.34 (0.38) | 2/2 | 32.69 (0.39) | 2/2 | 30.86 (1.51) | |

| 50 | 0/2 | 2/2 | 31.30 (0.18) | 2/2 | 33.67 (0.06) | 2/2 | 33.43 (0.36) | |

| 25 | 0/3 | 3/3 | 31.87 (0.34) | 3/3 | 34.27 (0.35) | 3/3 | 32.71 (1.38) | |

| 10 | 0/3 | 3/3 | 33.39 (0.16) | 3/3 | 36.16 (0.49) | 3/3 | 32.74 (0.53) | |

| 5 | 0/3 | 3/3 | 34.33 (0.38) | 3/3 | 36.89 (0.29) | 3/3 | 34.22 (0.45) | |

| 1 | 0/3 | 1/3 | 35.61 | 1/3 | 38.18 | 3/3 | 33.55 (0.69) | |

| 0 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 3/3 | 33.59 (1.59) | |||

| 10 | 10 | 0/3 | 3/3 | 36.45 (0.56) | 3/3 | 35.09 (0.44) | 3/3 | 34.46 (0.27) |

| 5 | 0/3 | 3/3 | 33.47 (0.09) | 3/3 | 36.11 (0.18) | 3/3 | 33.96 (0.19) | |

| 1 | 0/3 | 3/3 | 32.52 (0.35) | 3/3 | 39.23 (0.69) | 3/3 | 34.76 (0.84) | |

| 0 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 2/3 | 34.06 (2.01) | |||

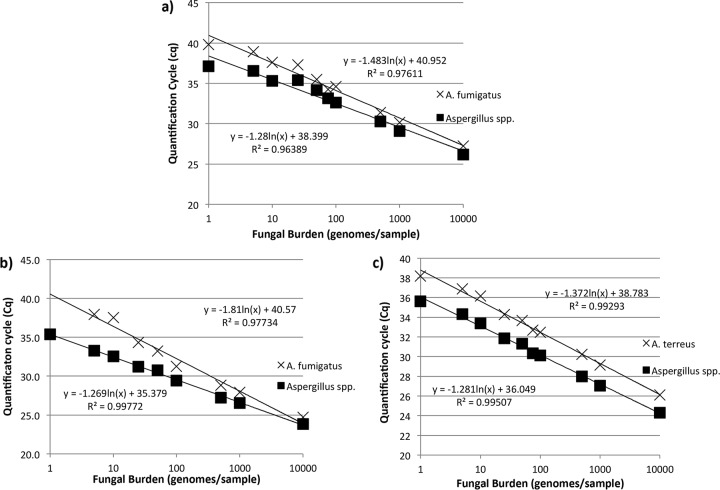

For the A. fumigatus and Aspergillus species assays, amplification was linear from 5 to 10,000 genomes/0.5-ml sample when EZ1 extracts were tested (Fig. 1a). The PCR efficiencies obtained using DNAs extracted from plasma by use of the EZ1 system were 96.3% and 118.5% for the A. fumigatus and Aspergillus species assays, respectively. For testing of EasyMag extracts, the linear range was also 5 to 10,000 genomes/0.5-ml sample for the A. fumigatus assay, but for the Aspergillus species assay, it was 1 to 10,000 genomes/0.5-ml sample (Fig. 1b). The PCR efficiencies obtained using DNAs extracted from plasma by use of the EasyMag system were 73.8% and 119.9% for the A. fumigatus and Aspergillus species assays, respectively. The linear range for both assays with A. terreus DNA extracted by use of the EasyMag system was 1 to 10,000 genomes/0.5-ml sample (Fig. 1c). The PCR efficiencies for testing of A. terreus DNA extracted from plasma by use of the EasyMag system were 107.3% and 118.3% for the A. terreus and Aspergillus species assays, respectively.

FIG 1.

Standard curves for the PathoNostics AsperGenius A. fumigatus and Aspergillus species assays for testing of A. fumigatus genomic DNA extracted from plasma samples by use of Qiagen EZ1 (a) and bioMérieux EasyMag (b) automated extractors and for the A. terreus and Aspergillus species assays for testing of A. terreus genomic DNA extracted from plasma samples by use of a bioMérieux EasyMag automated extractor (c).

Analytical performance of the AsperGenius resistance assay.

The 100% LOD for all resistance markers was 50 genomes/0.5-ml sample, and nonreproducible detection was achieved at 25 genomes/0.5-ml sample (50 to 75% reproducibility) and 10 genomes/0.5-ml sample (20% reproducibility). At 5 genomes/0.5-ml sample, only the region potentially containing the TR34 mutation was amplified, on 1/5 occasions; all other targets were consistently negative (0/5 occasions) at this burden level. All targets failed to be amplified when nucleic acid extracted from samples containing 1 genome of A. fumigatus DNA was tested. This information was used to determine the minimum fungal burden in a plasma sample that would permit successful amplification of the regions containing the potential resistance markers. For reproducible detection of these markers, the burden would need to be ≥50 genomes/0.5-ml sample, corresponding to a quantification cycle (Cq) value of <34 cycles for detection of DNA extracted by use of the EasyMag system with the A. fumigatus-specific assay. With nonreproducible detection of resistance markers expected for burdens between 5 and <50 genomes/0.5-ml sample, testing of A. fumigatus-positive samples with Cq values between 33 and 39 cycles may result in successful amplification of regions potentially harboring mutations conferring azole resistance.

Clinical evaluation.

There were 86 samples from 12 cases of IA tested, including 10 cases of proven/probable IA (72 samples) and 2 cases of possible IA (14 samples). Unfortunately, no cases were culture positive, and it was not possible to derive a species-level diagnosis. The median number of samples tested per case patient was 7 (range, 6 to 9). There were 125 samples from 27 patients with no evidence of invasive fungal disease that were included as controls; the median number of extracts tested per control patient was 5 (range, 3 to 5).

The positivity rates for samples from proven/probable cases were 15.3% (11/72 samples; 95% confidence interval [CI], 8.8 to 23.5 samples) and 25.0% (18/72 samples; 95% CI, 16.4 to 36.1 samples) for the A. fumigatus and Aspergillus species targets, respectively. All 11 A. fumigatus-positive results were concomitantly positive by the Aspergillus species assay, and there were seven additional positive results by the Aspergillus species assay (Table 4). Of the seven additional positive Aspergillus species assay results, four were for two patients who also had other samples positive by both the A. fumigatus and Aspergillus species assays, and three were from two patients who were consistently negative by the A. fumigatus assay (Table 4). The false positivity rates for samples from controls were 0.0% (0/125 samples; 95% CI, 0.0 to 3.0 samples) and 4.8% (6/125 samples; 95% CI, 2.2 to 10.1 samples) for the A. fumigatus and Aspergillus species targets, respectively. No samples (n = 14) from possible IA patients (n = 2) were positive by either assay. For both the A. fumigatus and Aspergillus species assays, the true positivity for proven/probable IA cases was significantly greater than the false positivity associated with the control population (for the A. fumigatus assay, the difference was 15.3% [95% CI, 8.1 to 25.3%] [P < 0.0001]; for the Aspergillus species assay, the difference was 20.2% [95% CI, 10.1 to 31.6%] [P < 0.0001). There were two cases of potential non-fumigatus disease, but no positive results were generated by the A. terreus-specific assay. Given the lower PCR efficiency of the A. fumigatus assay, it cannot confidently be determined whether Aspergillus species-positive/A. fumigatus-negative results represent infection by species other than A. fumigatus. Unfortunately, no culture data were available to provide species-level identification.

TABLE 4.

PathoNostics AsperGenius PCR positivity according to sample for cases of proven/probable invasive aspergillosisa

| Patient no. (EORTC/MSG diagnosisb) |

Cq value for sample: |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|||||||||

| Afumi | Asp | Afumi | Asp | Afumi | Asp | Afumi | Asp | Afumi | Asp | Afumi | Asp | Afumi | Asp | Afumi | Asp | |

| 1 (probable IA) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 38.0 | 37.1 | 37.0 | 36.1 | 37.6 | 36.5 | NT | NT |

| 2 (probable IA) | − | − | − | 37.1 | − | − | − | − | − | 33.1 | 40.4 | 32.6 | − | 36.0 | NT | NT |

| 3 (probable IA) | − | 33.2 | − | 34.7 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 4 (probable IA) | − | − | − | − | − | 42.2 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | NT | NT |

| 5 (Prob Asp Sin) | 37.7 | 36.2 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | NT | NT |

| 6 (probable IA) | − | − | − | 37.0 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 35.8 | 34.7 | NT | NT |

| 7 (probable IAc) | − | − | 44.8 | 38.7 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 8 (probable IA) | 34.3 | 31.8 | 44.7 | 36.8 | 37.4 | 34.7 | 46.3 | 37.6 | − | − | − | − | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 9 (probable IA) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | NT | NT |

| 10 (Prov Asp Sin) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | NT | NT |

Afumi, PathoNostics AsperGenius A. fumigatus assay; Asp, PathoNostics AsperGenius species assay; IA, invasive aspergillosis; Prob Asp Sin, probable Aspergillus sinusitis; Prov Asp Sin, proven Aspergillus sinusitis; NT, no sample tested; −, assay was negative.

The EORTC/MSG definitions are from reference 18.

The patient had a total of nine samples tested; the one additional sample tested was negative by both the A. fumigatus and Aspergillus species assays and was the last sample to be tested. It was excluded to avoid presentation difficulties.

The mean (± standard deviation [SD]) Cq values for true positive samples were 39.4 (±4.0) and 35.9 (±2.5) cycles for the A. fumigatus and Aspergillus species assays, respectively. The mean Cq value for Aspergillus species false-positive results was 37.1 (±1.4) cycles, which is larger than the Cq values for true positive results, although the numbers of samples were limited.

The overall combined clinical performance of the AsperGenius assay is shown in Table 5. Using a single positive PCR result to define patient positivity, only 6/10 proven/probable IA cases were positive by the A. fumigatus assay, compared to 8/10 cases by the Aspergillus species assay. Conversely, the specificity of the A. fumigatus assay was 100% (27/27 samples), compared to 77.8% (21/27 samples) for the Aspergillus species assay, and a multiple-sample positive PCR threshold was required to attain 100% specificity for the latter.

TABLE 5.

Clinical performance of the AsperGenius species assay for testing of sera from individuals with proven/probable IA (n = 10), possible IA (n = 2), and NEF (n = 27)a

| Parameter | Valueb |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proven/probable IA vs NEF |

Proven/probable/possible IA vs NEF |

|||

| Single-sample positive threshold | Multiple-sample (≥2) positive threshold | Single-sample positive threshold | Multiple-sample (≥2) positive threshold | |

| Sensitivity (n/N, % [95% CI]) | 8/10, 80.0 (49.0–94.3) | 5/10, 50.0 (23.7–76.3) | 8/12, 66.7 (39.1–86.2) | 5/12, 41.7 (19.3–68.1) |

| Specificity (n/N, % [95% CI]) | 21/27, 77.8 (59.2–89.4) | 27/27, 100 (87.5–100) | 21/27, 77.8 (59.2–89.4) | 27/27, 100 (87.5–100) |

| LR for positive result | 3.6 | >500* | 3.0 | >417* |

| LR for negative result | 0.26 | 0.5 | 0.43 | 0.44 |

| DOR | 14.0 | >1,000* | 7.0 | >947.7* |

Performance represents a combination of results for the A. fumigatus-specific and broad-range Aspergillus species assays, as in a clinical scenario a positive result in either assay would carry significance. IA, invasive aspergillosis; NEF, no evidence of fungal disease; LR, likelihood ratio; DOR, diagnostic odds ratio.

*, to overcome infinity, the parameter was determined using a specificity value of 99.9%.

The amplification of regions harboring potential mutations associated with azole resistance direct from a sample was successful for only two patients, and neither contained the TR34/L98H or TR46/T289A/Y121F mutations. Amplification was unsuccessful for another four probable IA cases.

DISCUSSION

The performance of the PathoNostics AsperGenius assay for the detection of Aspergillus DNA in plasma samples was satisfactory. Both sensitivity (80%) and specificity (78%) were comparable to those generated by meta-analytical reviews for testing of blood, where sensitivity ranged from 84 to 88% and specificity ranged from 75 to 76% (11, 12). In the previously published evaluations of the AsperGenius assay, the sensitivity and specificity for testing of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid were 84% and 91%, respectively, and those for testing of serum were 79% and 91%, respectively (7, 8). While sensitivity appears to be consistent across specimen types, specificity for testing of plasma was compromised, although the sample numbers were limited in all studies. In both the serum and BAL fluid studies, optimal positivity thresholds could be defined, and in the case of serum testing, a threshold of 39 cycles improved the specificity to 100%, without compromising sensitivity (7, 8). In the current study, it was not possible to generate a threshold, as false-positive results had Cq values similar to those for true positive results for cases of aspergillosis. As with serum testing, if more than one sample per patient was positive, then the specificity was 100%, but sensitivity was duly compromised (Table 5) (7).

In the recent studies of the EAPCRI, it was shown that the analytical and subsequent clinical performances of Aspergillus PCR could be improved by testing plasma instead of serum (3, 4). It was hypothesized that by performing the AsperGenius assay on DNA extracted from plasma, an improvement in performance would be evident. For analytical performance, this was observed by comparing PCR efficiencies for testing of 5 μl of DNA extracted from serum or plasma by use of the EZ1 system, which showed that the PCR efficiencies of both the A. fumigatus and Aspergillus species assays improved with testing of plasma (for the A. fumigatus assay, 72.6% with serum versus 96.3% with plasma; for the Aspergillus species assay, 106% with serum versus 118.5% with plasma) (7). Conversely, the PCR efficiency of the A. fumigatus assay for testing of DNA extracted by use of the EasyMag system was superior for serum (for the A. fumigatus assay, 97%; for the Aspergillus species assay, 124%) over that for plasma (for the A. fumigatus assay, 74%; for the Aspergillus species assay, 120%) (7). These data highlight that PCR efficiency can be severely compromised by the quality of the nucleic acid extracted and the necessity to optimize the extraction process for each sample type. However, if the standard curve of the A. fumigatus assay for testing of DNA extracted by use of the EasyMag system is examined in detail (Fig. 1b), it can be argued that the detection of burdens of ≤10 genomes/0.5-ml sample is outside the linear range of the assay. Removal of these burdens from the standard curve increases the coefficient of determination to 0.99 and the PCR efficiency to 90%, comparable to the values for testing of DNA extracted from serum by use of the EasyMag system.

In a previous study comparing the analytical performances of automated nucleic acid extraction platforms for use with Aspergillus PCR, the EasyMag system was associated with high-quality DNA and subsequent lower Cq values but was also associated with Aspergillus contamination (13). The increase in PCR efficiency for testing of DNA extracted from plasma by use of the EZ1 system was not significantly associated with an improved LOD for either assay, although using the EasyMag extractor and a larger DNA template volume did improve recovery of lower burdens. The reproducibility of detection for testing of 1 genome/0.5-ml sample extracted by use of the EasyMag system was 60% (Table 2). There were four false-positive A. terreus results in the analytical study, whereas false positivity in the clinical study was associated with the Aspergillus species target. No negative-control samples for extraction generated false-positive results. Given the different identities of false positivity in the clinical and analytical arms and the low level of overall false positivity, it was felt that this was not directly associated with the EasyMag extractor, as previously documented, but represented the false positivity typically encountered in testing of clinical samples or an analytical cross-reactivity between Aspergillus species (13).

For all clinical samples, 10 μl of EasyMag extract was used for PCR amplification. This did not result in improved clinical performance, with no significant improvement in sensitivity but a reduction in specificity, meaning that the diagnostic odds ratio was lower with plasma than that with serum. One potential explanation for this unexpected result is that while the use of the larger volume potentially increased the reproducibility of detection of the smaller burdens (<10 genomes/0.5-ml sample), these low concentrations were more likely to be affected by sample degradation. Given the retrospective nature of the study, it is hypothesized that samples containing low burdens had degraded to below detectable levels, minimizing any benefits associated with using a larger template volume.

A second explanation for the lack of improvement in clinical performance is that although the larger input volume increased the opportunity for detecting target DNA, it also increased the potential for the presence of inhibitory compounds. Only two extractions exhibited total inhibition (no internal control [IC] signal present), but another three generated Cq values that were larger than the upper limit generated by the manufacturer, indicating a degree of partial inhibition. One concern in interpreting the IC for testing of plasma or serum is the relatively high concentration of IC with respect to typical Aspergillus PCR-positive results for blood and the subsequent acceptable IC Cq range proposed by the manufacturer. The acceptable Cq values for the IC range from 29.5 to 35.0 cycles; in this study, 86.2% (182/211 samples) of samples had an IC Cq value within this range, with 2.4% (5/211 samples) of samples exhibiting partial or total inhibition (Cq > 35.0 cycles). A further 11.4% (24/211 samples) of samples had an IC Cq value below the lower acceptable limit (range, 26.1 to 29.4 cycles), and while this cannot represent inhibition, it raises questions about the robustness of the IC PCR for testing of DNA template input volumes greater than the 5 μl recommended by the manufacturer. This diversity (median IC Cq, 33.6 cycles; range, 26.1 to 36.4 cycles) makes it difficult to determine a typical (expected) reference value from which inhibition in specimens can be derived. The relatively high IC concentration was developed for use with BAL fluid samples, for which fungal burdens will be greater and lower Cq values generated. Consequently, the typical IC value is significantly lower than that for Aspergillus PCR-positive results for testing of serum and plasma samples (typically >35 cycles). As such, the effect of any inhibitory compounds on the IC PCR may be less evident than that experienced with a clinical plasma sample, where an inhibitory delay of 2 to 3 cycles will result in PCR negativity but keep the IC Cq within the manufacturer's acceptable range, resulting in potential false-negative results.

In addition to inhibitory compounds, the presence of interfering substances should also be considered. In a previous EAPCRI study, the presence of fibrinogen in plasma was proposed to have the potential to influence the magnesium concentration, which is critical to optimal PCR performance (4). It is possible that fibrinogen is present in nucleic acid eluates and that this interferes with PCR amplification. With the larger input volume, this may have affected the performance of the AsperGenius assay and may explain the wide-ranging IC Cq values (e.g., why the mean IC Cq values for 2/5 simulated samples extracted by use of the Qiagen EZ1 system and amplified using 10 μl of template were very high/late [Table 1]).

Although the use of 10 μl of EasyMag eluate improved the detection of low burdens, the PCR efficiency for 10 μl of template was not calculated because the range of burdens tested using a 10-μl input was limited to 1 log. Further limitations of the study were that it was not possible to perform a direct comparison with the previous serum study and the samples included were different. With hindsight, it may have been wise to perform the plasma testing using 5 μl of template, as the improvement in efficiency over that with serum was confirmed and this volume was used for the previous serum study (7). Currently, the AsperGenius assay is fully validated only for in vitro diagnostic testing of BAL fluid samples, which has implications for interpreting positive results from blood samples. The positivity threshold for the species assay for testing of BAL fluid is <36 cycles; for testing of blood, this is likely too early, as the median Cq was 35.9 cycles for clinical PCR-positive results and 11/18 samples (61.1%) had Cq values of ≥36.0 cycles. It is important to remember that for testing of blood specimens by Aspergillus PCR, the strategy is to exclude disease by using a negative result generated by frequent screening with a highly sensitive assay; thus, a Cq threshold is not essential, albeit at the expense of false-positive results.

The regions potentially associated with azole resistance were successfully amplified from only two cases of IA. Given the costs associated with both the AsperGenius species multiplex (approximately $1,000/50 reactions) and AsperGenius resistance multiplex (approximately $1,600/50 reactions of both the species and resistance multiplex assays) assays, it may be difficult to justify the costs associated with direct-from-plasma resistance testing. However, if direct resistance testing is applied only to samples strongly positive by the species assay, then wastage associated with failed amplification can be limited. Costs for screening with the species assay may be offset by reductions in the unnecessary use of antifungal therapy, as seen in other studies where Aspergillus PCR in combination with a galactomannan enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was shown to reduce the use of empirical therapy (14–16).

To conclude, the PathoNostics AsperGenius assay can be used to perform PCR testing on plasma and will provide a performance that is comparable to that for testing serum. Unexpectedly, the predicted improvements in clinical performance associated with plasma testing were not seen, possibly as a result of the retrospective study design or the impact of larger concentrations of inhibitory/interfering compounds. Considering the latter, the current IC for the PathoNostics AsperGenius assay showed too much variability to confidently predict inhibition, although this may have been a result of using a larger template volume. The study also highlights the necessity to individually evaluate PCR assays for testing of different specimen types. Assays have various master mix compositions and reaction kinetics, which may not be optimal across samples and subsequent eluate makeups. The clinical utility of commercially available Aspergillus PCR assays, such as the AsperGenius assay, requires prospective evaluation, with particular reference to the impact of potential early diagnosis of azole-resistant disease on patient management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

The study was divided into an analytical evaluation to determine each assay's limit of detection (LOD), linear range, and efficiency of amplification for testing of plasma and a clinical study to determine the performance (sensitivity, specificity, etc.) for testing of plasma samples from a hematology population at high risk of IA.

Analytical study.

The analytical evaluation focused on performance for testing of specimens containing genomic DNA from A. fumigatus or A. terreus. Two automated nucleic acid extraction systems were evaluated (Qiagen DSP virus kit on an EZ1 Advance XL instrument and the bioMérieux Generic 2.01 protocol on an EasyMag instrument). All nucleic acids were eluted in 60 μl.

Simulated plasma samples were prepared by using pooled human plasma divided into 0.5-ml aliquots and spiked with various concentrations of genomic DNA from either A. fumigatus or A. terreus to achieve final burdens of 10,000, 1,000, 500, 100, 75, 50, 25, 10, 5, and 1 genome/0.5-ml sample. Successful detection of the higher burdens was predicted, so in order to determine accurate performance at less predictable concentrations, the number of replicates was larger for testing lower burdens (Tables 1 to 3). To monitor for contamination during each extraction process, at least one nonspiked plasma aliquot was retained to provide a negative control. To avoid airborne contamination, all required manual processes took place in a class II laminar flow cabinet.

For PCR amplification, a 5-μl DNA template input volume was used for all burdens, with an additional 10-μl input assessed for the lower burdens (<50 genomes/0.5-ml sample) in an attempt to improve the reproducibility of detection.

Clinical study and patient population.

Clinical plasma samples from patients with proven, probable, or possible IA or with no evidence of fungal disease were selected. All samples had been sent as part of a care pathway incorporating a well-validated “in-house” Aspergillus PCR (16, 17). On completion of routine testing, plasma was stored at −80°C for quality control or performance assessment purposes. The study was a performance assessment of the AsperGenius assay and had an anonymous, retrospective, case-control design not affecting patient management. Patient demographics are shown in Table 6. Nucleic acid was extracted from 0.5 ml of plasma by use of the bioMérieux EasyMag Generic 2.01 protocol following the manufacturer's instructions, with DNA eluted in a 60-μl volume. Positive (plasma containing 10 genomes of A. fumigatus DNA) and negative (plasma only) extraction controls were included in each run.

TABLE 6.

Patient demographics and diagnosis of IA according to the revised EORTC/MSG definitionsa

| Parameter | Value or description for individuals with: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Proven/probable IA (n = 10) | Possible IA (n = 2) | NEF (n = 27) | |

| No. of males/no. of females | 6/4 | 1/1 | 15/12 |

| Median age (range) (yr) | 60.5 (25–74) | NA (18–51) | 56 (21–76) |

| Underlying condition (no. of patients) | AML (7) | AML (1) | AML (17) |

| ALL (2) | ALL (1) | Lymphoma (6) | |

| MDS (1) | AA (2) | ||

| ALL (1) | |||

| MDS (1) | |||

| No. of patients with allogeneic stem cell transplantation | 6 | 2 | 19 |

| Fungal prophylaxis (no. of patients) | Fluconazole (9) | Fluconazole (2) | Fluconazole (15) |

| Voriconazole (1) | |||

| Fungal disease manifestation (no. of patients) | Proven Aspergillus sinusitis (1) | Possible IPA (2) | NA |

| Probable IPA (6) | |||

| Probable IPA/sinusitis (2) | |||

| Probable sinusitis (1) | |||

The revised EORTC/MSG definitions are from reference 18. AA, aplastic anemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; lymphoma, Hodgkin's, non-Hodgkin's, or Burkitt's lymphoma; IPA, invasive pulmonary aspergillosis; NA, not applicable.

For PCR amplification, a 10-μl DNA template volume was used to provide optimal opportunity for detection.

PathoNostics AsperGenius PCR amplification.

For both the analytical and clinical studies, AsperGenius species and resistance PCR testing was performed on a Qiagen Rotorgene Q high-resolution-melt instrument, using a final reaction volume of 25 μl and following the manufacturer's instructions, with the exceptions that the DNA template volume for the species assay was increased to 10 μl for the clinical evaluation, and in the analytical evaluation the performance for detection of the lower burdens (<50 genomes/0.5-ml sample) was determined with input volumes of 5 and 10 μl. The manufacturer recommends input volumes of 5 and 10 μl for the species and resistance assays, respectively.

Statistical evaluation.

Analytical analysis of the AsperGenius species PCR for testing of plasma samples was performed as previously described (7). Briefly, the 100% LOD, linearity ranges, and PCR amplification efficiencies were calculated. Further analysis was performed to correlate AsperGenius species and resistance assay performances so that the quantification cycle (Cq) generated by the A. fumigatus assay could be used as a guide to the likelihood of success in performing the resistance assay.

In determining the clinical accuracy of the AsperGenius species results, the positivity rate for samples originating from case patients was compared to the false positivity rate for control samples. Clinical performance was determined by the construction of 2 × 2 tables to calculate the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios, and diagnostic odds ratio for the AsperGenius species assay. For all patients, only a single positive sample was required to consider the patient positive. Given the case-control study design and the artificially high prevalence of proven/probable IA (25.6%), predictive values were not used. Where required, 95% confidence intervals and P values (Fisher's exact test; P values of <0.05 were considered significant) were generated to determine the significance of the differences between rates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

P.L.W. is a founding member of the EAPCRI, received project funding from Myconostica, Luminex, Renishaw Diagnostics, and Bruker, was sponsored by Myconostica, MSD, Launch, Bruker, and Gilead Sciences to attend international meetings, provided consultancy for Renishaw Diagnostics Limited, and is a member of the advisory board and speakers' bureau for Gilead Sciences. R.A.B. is a founding member of the EAPCRI, received an educational grant and scientific fellowship award from Gilead Sciences and Pfizer, is a member of the advisory boards and speakers' bureaus for Gilead Sciences, MSD, Astellas, and Pfizer, and was sponsored by Gilead Sciences and Pfizer to attend international meetings. R.B.P. has no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.White PL, Bretagne S, Klingspor L, Melchers WJG, McCulloch E, Schulz B, Finnstrom N, Mengoli C, Barnes RA, Donnelly JP, Loeffler J, European Aspergillus PCR Initiative. 2010. Aspergillus PCR: one step closer to standardization. J Clin Microbiol 48:1231–1240. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01767-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White PL, Mengoli C, Bretagne S, Cuenca-Estrella M, Finnstrom N, Klingspor L, Melchers WJ, McCulloch E, Barnes RA, Donnelly JP, Loeffler J, European Aspergillus PCR Initiative (EAPCRI). 2011. Evaluation of Aspergillus PCR protocols for testing serum specimens. J Clin Microbiol 49:3842–3848. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05316-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White PL, Barnes RA, Springer J, Klingspor L, Cuenca-Estrella M, Morton CO, Lagrou K, Bretagne S, Melchers WJG, Mengoli C, Donnelly JP, Heinz WJ, Loeffler J. 2015. The clinical performance of Aspergillus PCR when testing serum and plasma—a study by the European Aspergillus PCR Initiative. J Clin Microbiol 53:2832–2837. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00905-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loeffler J, Mengoli C, Springer J, Bretagne S, Cuenca Estrella M, Klingspor L, Lagrou K, Melchers WJG, Morton CO, Barnes RA, Donnelly JP, White PL. 2015. Analytical comparison of in vitro spiked human serum and plasma for the PCR-based detection of Aspergillus fumigatus DNA—a study by the European Aspergillus PCR Initiative. J Clin Microbiol 53:2838–2845. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00906-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arvanitis M, Anagnostou T, Mylonakis E. 2015. Galactomannan and polymerase chain reaction-based screening for invasive aspergillosis among high-risk hematology patients: a diagnostic meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 61:1263–1272. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White PL, Hibbitts SJ, Perry MD, Green J, Stirling E, Woodford L, McNay G, Stevenson R, Barnes RA. 2014. Evaluation of a commercially developed semi-automated PCR-SERS assay for the diagnosis of invasive fungal disease. J Clin Microbiol 52:3536–3543. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01135-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White PL, Posso RB, Barnes RA. 2015. Analytical and clinical evaluation of the PathoNostics AsperGenius assay for detection of invasive aspergillosis and resistance to azole antifungal drugs during testing of serum samples. J Clin Microbiol 53:2115–2121. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00667-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chong GL, van de Sande WW, Dingemans GJ, Gaajetaan GR, Vonk AG, Hayette MP, van Tegelen DW, Simons GF, Rijnders BJ. 2015. Validation of a new Aspergillus real-time PCR assay for direct detection of Aspergillus and azole resistance of Aspergillus fumigatus on bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. J Clin Microbiol 53:868–874. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03216-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White PL, Perry MD, Moody A, Follett SA, Morgan G, Barnes RA. 2011. Evaluation of analytical and preliminary clinical performance of Myconostica MycAssay Aspergillus when testing serum specimens for diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol 49:2169–2174. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00101-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guinea J, Padilla C, Escribano P, Muñoz P, Padilla B, Gijón P, Bouza E. 2013. Evaluation of MycAssay™ Aspergillus for diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients without hematological cancer. PLoS One 8:e61545. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arvanitis M, Ziakas PD, Zacharioudakis IM, Zervou FN, Caliendo AM, Mylonakis E. 2014. PCR in diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis: a meta-analysis of diagnostic performance. J Clin Microbiol 52:3731–3742. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01365-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mengoli C, Cruciani M, Barnes RA, Loeffler J, Donnelly JP. 2009. Use of PCR for diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis: systematic review of and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 9:89–96. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perry MD, White PL, Barnes RA. 2014. Comparison of four automated nucleic acid extraction platforms for the recovery of DNA from Aspergillus fumigatus. J Med Microbiol 63:1160–1166. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.076315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrissey CO, Chen SC, Sorrell TC, Milliken S, Bardy PG, Bradstock KF, Szer J, Halliday CL, Gilroy NM, Moore J, Schwarer AP, Guy S, Bajel A, Tramontana AR, Spelman T, Slavin MA, Australasian Leukaemia Lymphoma Group, Australia and New Zealand Mycology Interest Group. 2013. Galactomannan and PCR versus culture and histology for directing use of antifungal treatment for invasive aspergillosis in high-risk haematology patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 13:519–528. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aguado JM, Vázquez L, Fernández-Ruiz M, Villaescusa T, Ruiz-Camps I, Barba P, Silva JT, Batlle M, Solano C, Gallardo D, Heras I, Polo M, Varela R, Vallejo C, Olave T, López-Jiménez J, Rovira M, Parody R, Cuenca-Estrella M, PCRAGA Study Group, Spanish Stem Cell Transplantation Group, Study Group of Medical Mycology of the Spanish Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases. 2015. Serum galactomannan versus a combination of galactomannan and PCR-based Aspergillus DNA detection for early therapy of invasive aspergillosis in high-risk hematological patients: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 60:405–414. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnes RA, Stocking K, Bowden S, Poynton MH, White PL. 2013. Prevention and diagnosis of invasive fungal disease in high-risk patients within an integrative care pathway. J Infect 67:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White PL, Linton CJ, Perry MD, Johnson EM, Barnes RA. 2006. The evolution and evaluation of a whole blood polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection of invasive aspergillosis in hematology patients in a routine clinical setting. Clin Infect Dis 42:479–486. doi: 10.1086/499949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, Pappas PG, Maertens J, Lortholary O, Kauffman CA, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Maschmeyer G, Bille J, Dismukes WE, Herbrecht R, Hope WW, Kibbler CC, Kullberg BJ, Marr KA, Muñoz P, Odds FC, Perfect JR, Restrepo A, Ruhnke M, Segal BH, Sobel JD, Sorrell TC, Viscoli C, Wingard JR, Zaoutis T, Bennett JE, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. 2008. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 46:1813–1821. doi: 10.1086/588660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]