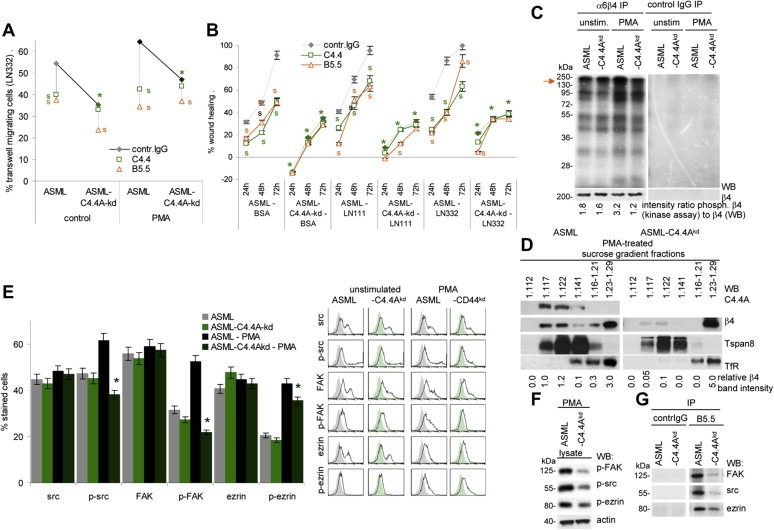

Figure 2.

Reduced motility of ASML‐C4.4Akd cells is accompanied by impaired alpha6beta4 activation and raft recruitment: (A) Untreated orPMA treated ASML and ASML‐C4.4Akd cells were seeded in the upper part of a Boyden chamber. The lower chamber contained LN332 (804G supernatant). Where indicated cells were pre‐incubated with C4.4 (anti‐C4.4A) or B5.5 (anti‐alpha6beta4). Migration was evaluated after 16 h by staining the lowermembrane site with crystal violet. The % of migration cells (mean of triplicates) is shown. Significant differences between ASML and ASML‐C4.4Akd cells: *, significant antibody inhibition of migration: s. (B) ASML and ASML‐C4.4Akd cells were seeded in 24‐well plates coated with BSA, LN111 or LN332. When reaching subconfluence, the monolayer was scratched. “Wound healing” was evaluated for 72 h by light microscopy. Where indicated, the cultures contained C4.4 or B5.5. The mean percent ± SD(quadruplicates) of wound closure (as compared to the wound area at the time of scratching) is shown. Significant differences between ASML and ASML‐C4.4Akd cells: *; significant differences between control IgG, C4.4 and B5.5: s. (C) In vitro kinase assay of alpha6beta4 and control IgG immunoprecipitates of unstimulated and PMA‐stimulated ASML and ASMLC4.4Akd cell lysates. WB with anti‐beta4 served as loading control. The ratio of the signal strength of phosphorylated alpha6beta4 (kinase assay) to beta4 is indicated. (D) Lysates of PMA‐treated ASML and ASML‐C4.4Akd cells were separated by sucrose density gradient. Fractions were separated by SDS‐PAGE and after transfer blotted with C4.4 and anti‐beta4. Tspan8 (D6.1) serves as control raft marker and the transferin receptor (TfR (Ox26) as non‐raft marker. The relative 4 band intensity in sucrose fractions is shown. (E) Src, p‐src, FAK, p‐FAK, ezrin and p‐ezrin expression was evaluated by flow cytometry in untreated and PMA‐treated ASML and ASML‐C4.4Akd cells. Representative examples and mean values ± SD (triplicates) of stained cells are shown. Significant differences between ASML and ASML‐C4.4Akd cells: *. (F) Lubrol lysates of PMA‐treated ASML and ASML‐C4.4Akd cells were SDS‐PAGE separated and after transfer blotted with anti‐p‐FAK, anti‐p‐src and anti‐p‐ezrin and anti‐actin. (G) Lubrol lysates ofPMA‐treated ASMLand ASML‐C4.4Akd cells were precipitated with B5.5 (anti‐alpha6beta4) and control IgG. Immunoprecipitates were blotted with anti‐FAK, anti‐src and anti‐ezrin. (All experiments shown in Figure 2 were performed with ASMLwt and ASMLmock cells as well as with ASML‐C4.4Akd clone 30c and 34c cells revealing comparable results.) Stimulation‐promoted migration of ASMLwt cells is inhibited by anti‐C4.4A and anti‐alpha6beta4. Instead, poor migration of ASML‐C4.4Akd cells is hardly affected by alpha6beta4 blocking. Pronounced motility of ASML cells depends on recruitment of alpha6beta4 into rafts and beta4 phosphorylation, where alpha6beta4 supports src and FAK phosphorylation. Yet, beta4 may not directly associate with src and FAK as co‐immunoprecipitation was only observed under mild lysis conditions.