Abstract

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is an illness that has a potentially life-threatening condition that affects a large percentage of the global population. VTE with pulmonary embolism (PE) is the third leading cause of death after myocardial infarction and stroke. In the first three months after an acute PE, there is an estimated 15% mortality among submassive PE, and 68% mortality in massive PE. Current guidelines suggest fibrinolytic therapy regarding the clinical severity, however some studies suggest a more aggressive treatment approach. This review will summarize the available endovascular treatments and the different techniques with its indications and outcomes.

Keywords: Pulmonary embolism, Massive pulmonary embolism, Venous thromboembolism, Pulmonary embolism treatment, Submassive pulmonary embolism, Catheter directed therapy, Interventional radiology

Core tip: Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is an illness that is potentially life-threatening condition that affects a large percentage of the global population. VTE is the third leading cause of death related with cardiovascular pathology after myocardial infarction and stroke. This article summarizes the clinical management and emphasizes which interventional treatments that exist and the most effective ones to treat massive and submassive pulmonary embolism.

INTRODUCTION

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a life-threatening condition that affects a large percentage of the global population; VTE includes the deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). The incidence rate of VTE is 100 cases per 100000 inhabitants in Europe[1] and 160 per 100000 inhabitants in the United States[2]. VTE is the third leading cause of death after myocardial infarction and stroke. In the first three months after an acute PE, there is an estimated of 15% mortality among submassive PE, and 68% mortality in massive PE[3]. Acute PE is also the leading cause of pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular failure[4].

From the clinical point of view, two different situations need to be considered, prognosis and therapeutic management. For a massive PE there are three different treatments options: (1) systemic thrombolysis; (2) Surgical pulmonary embolectomy; and (3) Endovascular techniques[5]. Other authors also advocate to implant an inferior vena cava filter (IVCf) in massive PE to prevent further thrombus migration and avoid higher thrombotic load or avoid anticoagulation therapy. According to the clinical guidelines of the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) an interventional approach, in an acute massive PE, currently is only considered the treatment of choice when a systemic thrombolysis therapy fails or is contraindicated[6]; however other authors advocate the use of the following procedures: Catheter directed therapy (CDT), mechanical fragmentation, thrombectomy procedures as a more aggressive therapeutic management that can provide excellent results in a massive PE[7-10]. Since there are a variety of CDT and thrombectomy methods, more prospective studies are still needed to refine the interventional approach protocol and determine the safest techniques in larger cohorts. This review will outline the different clinical presentation of PE, and will summarize the available endovascular treatments and the different techniques with its indications and outcomes.

TYPES AND DEFINITIONS OF PE

The two main subtypes of PE that are necessary to address are the submassive (intermediate risk) and massive PE (high risk). The most frequent clinical symptoms are dyspnea (82%) and chest pain (49%), but it can also present: Cough (20%), syncope(14%) and Hemoptysis (7%)[3].

Massive PE is defined as an hemodynamically unstable condition which has clinical presentation with low blood pressure (systolic pressure < 90 mmHg or a decrease of more than 40 mmHg in baseline systolic pressure) and may develop a cardiac arrest. Other clinical manifestations related to hypotension may be present, such as tissue hypoperfusion and hypoxemia[11].

Submassive PE (intermediate risk) is defined as a hemodynamically stable condition (normal blood pressure) with a right ventricular dysfunction or elevated cardiac biomarkers which can develop a reduced workload and an increased strain on the heart[5].

It should not be confused with the radiological definitions of “massive” PE in which the criteria are related to the quantity of thrombus within the pulmonary trunk or the arterial pulmonary branches instead of the clinical presentation of the PE. A “massive” PE, from the radiological point of view, is described as a reduction of of lung perfusion in one lung (> 90%) or total occlusion of a main pulmonary artery diagnosed with a pulmonary CT angiography[12].

Mortality in massive PE patients with hemodynamic shock can reach a 68% in the first hours after diagnosis[13]. However In submassive PE the mortality is lower compared to a massive PE.

The American College of Chest Physicians in their guidelines differentiates the considered treatment for both situations[6]. While in the massive PE, thrombolysis (Class IIa, Level of Evidence B) is recommended as the first option, in a submassive PE the thrombolysis is controversial. Thrombolysis may be indicated in submassive PE with a poor prognosis (RV dysfunction, severe respiratory failure, myocardial necrosis) and low risk of bleeding (Class IIb level of evidence C). In the rest, thrombolysis is not recommended (Class III, level of evidence B).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF MASSIVE PE

The severity of a massive PE is directly related to the amount of thrombus occluding the pulmonary arteries and the underlying cardiopulmonary status of the patient, which causes hemodynamic instability[14]. A significant obstruction of the pulmonary vascular bed produces hypoxemia and results in the release of potent vasoconstricting substances that further aggravate the systemic hypoxia, with an increase in pulmonary arterial resistance that can cause an elevated right ventricular afterload[15]. Right ventricular overload produces hypokinesia and ventricular dilatation with tricuspid regurgitation; in which can eventually lead to right ventricular failure. Increased pressure in the right ventricle (RV) may cause alteration in the cardiac wall with ischemia or myocardial infarction due to an increase in the demand for oxygen and a decrease in the supply. In addition, stress on the myocardial wall along with systemic arterial hypotension decreases the perfusion to the coronary arteries, which can also lead to RV ischemia with or without infarction[16]. All of these changes may lead to RV failure, diminished left ventricular output and life-threatening hemodynamic shock[13].

MASSIVE PE DIAGNOSIS

Clinical manifestations play an important role in the differential diagnosis between massive PE and non-massive PE. Hemodynamic instability with suspected PE (blood pressure < 90 mmHg) establishes the diagnosis of massive PE, while to diagnose a submassive PE it is essential to rule out right ventricular dysfunction by echocardiography and/or elevated cardiac biomarkers. Computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) should report the size of the thrombus and percentage of occlusion of the pulmonary arteries. The amount and size of the thrombus should not be used to differentiate between clinical massive and submassive PE. If the patient has a good pulmonary reserve, a massive embolism (high thrombotic load) does not always have an hemodynamic repercussion. CTPA also provides information on pulmonary vascular perfusion as well as other chest findings such as pleural effusion, pneumonic foci, neoplasia, etc. Finally CTPA can also describe RV failure by comparison of the diameter of the RV with the left ventricle (LV) and determine RV dilatation (RV/LV ratio > 1)[17]. The main echocardiographic signs of submassive PE are RV dilation and septum deviation to the LV[16,18]. Clinical history and physical examination are the key to establish the prognostic signs of severity. The International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER) identifies many clinical factors that can predict an increased mortality at 30 d (Table 1)[3]. Ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scanning is reserve as a diagnostic tool only in patients in whom CTPA is contraindicated or inconclusive and V/Q scanning should only be performed in patients with normal chest radiograph[19].

Table 1.

Predictive factors of severity and 30-d mortality

| Predictors of 30-d mortality |

| Cardiac failure |

| COPD |

| Systolic pressure < 100 mmHg |

| Age over 70 yr |

| Heart rate > 100 bpm |

| ECG signs of RV dysfunction |

| Elevated cardiac biomarkers (Troponins, BNP, H-FABP) |

| CT findings: RV enlargement |

| Echocardiography findings: |

| RV hypokinesis and dilatation |

| Deviation of the interventricular septum |

| Tricuspid regurgitation > 2.6 m/s |

| Loss of inspiratory collapse of the inferior vena cava |

| Patent foramen ovale |

Modified from Pizza et al[16]. COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; bpm: Beat per minute; ECG: Electrocardiogram; BNP: Brain-type natriuretic peptide; H-FABP: Heart-type fatty acid-binding protein; RV: Right ventricle; CT: Computed tomography.

Other supportive diagnostic tools include elevated d-dimer, cardiac biomarkers, DVT diagnosed with lower limb duplex, and RV dysfunction and elevated pulmonary pressure with echocardiography[20].

MEDICAL TREATMENT AND SUPPORT IN MASSIVE AND SUBMASSIVE PE

It is important from the outset to establish if the PE has hemodynamic stability, and to choose the appropriate therapeutic guideline. The ACCP[6] in its guidelines for the treatment and management of pulmonary PE recommends systemic fibrinolytic agent for massive PE with hemodynamic instability and low bleeding risk (Grade 1B). While a patient with a low risk PE it is only recommended anticoagulation therapy. However, the treatment of submassive PE is controversial. For submassive PE, the ACCP currently recommends, in selected patients with acute PE who deteriorate after starting anticoagulant therapy but have yet not develop a hypotension and who have a low bleeding risk, they suggest systemically administered fibrinolytic therapy. In patients who have a higher risk of bleeding with systemic fibrinolytic therapy, the physicians with access to CDT are likely to choose this treatment over systemic fibrinolytic therapy[6].

Massive and submassive PE has an important mortality in the first few hours, therefore urgent diagnosis and therapeutic approach is required[13]. It has been established that more than 25% of patients diagnosed with massive PE with hemodynamic instability die within the first two weeks[3,7]. The first therapeutic measures with fluid therapy and vasoactive drugs (dopamine, noradrenaline, etc.) should be directed to correct the hypotension and the RV failure. It is important to maintain patent airway with good oxygen supply, if necessary with tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation, to improve oxygenation and prevent respiratory failure.

Anticoagulation treatment, if there is no contraindication, should be administered immediately. Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin can be used in therapeutic range. ACCP recommends systemic thrombolysis in the case of massive PE with haemodynamic instability, and low bleeding risk. Urokinase (UK) and recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (r-TPA) are used as fibrinolytic substances. For massive PE, standard doses are: UK 4400 IU/kg per hour in 12-24 h, streptokinase 250000 IU bolus and then 100000 U/h for 12-24 h, or 1500000 U over 2 h, and 100 mg r-TPA over 2 h. The UKEP study did not demonstrate significant differences between 12 and 24-h therapeutic regimens in terms of safety and efficacy[21]. Other studies have used higher doses of UK (3 million IU) and streptokinase (1.5 million IU) in two hours with similar efficacy and safety results (Table 2)[22,23].

Table 2.

Fibrinolytic treatments used in massive pulmonary embolism

| Fibrinolytic agent | Infusion treatment 12-24 h | Short infusion treatment |

| Urokinase | 4400 IU/kg (bolus/30 min) + 4400 IU/kg per hour 12-24 h | 3 million IU/2 h |

| Streptokinase | 250000 IU (bolus/15 min) + 100000 IU/h 12-24 h | 1.5 million IU/2 h |

| r-tPA | N/A | 100 mg/2 h |

N/A: Not applicable.

Currently the ACCP guidelines[6] recommend short treatments of 2 h of fibrinolytic agents for massive PE (Recommendation Grade 2C). In submassive PE, the ACCP[6]. recommends the use of fibrinolytics only in cases of clinical deterioration despite anticoagulation. In this case the doses to be used will be the same as for the massive PE, however some advocate for half-dose of r-TPA to decrease the bleeding risk.

Regarding the route of administration, the systemic effect is recommended in severe PE. However, when the patient has a high risk of bleeding or the systemic therapy hasn’t been effective, a lower-dose fibrinolytic therapy can be administered via catheter placed within the pulmonary artery or directly in the thrombus; this procedure may be performed with or without thrombectomy and/or clot fragmentation. Regarding massive PE, Kuo et al[9] in their recent multicenter study, showed that a catheter-directed therapy (CDT) improves pulmonary hypertension and RV function effectively without more complications.

When pharmacological treatment (anticoagulant or thrombolysis) fails or is contraindicated, an IVCf can be implanted to prevent the migration of thrombi to the lung from a previous DVT (Recommendation Grade 1B). There are many types of filters on the market with similar efficacy and safety, although there are few comparative studies[7]. The development of the retrievable filters has expanded its use since it is possible to recover the IVCf once as filtration is no longer necessary or the risk of embolism has been resolved[24,25]. In the long term, The IVCf may become a thrombogenic device as and therefore may require long-term anticoagulant treatment to mitigate the risk of filter-related thrombosis[26]. The FDA in 2010 issued a recommendation advising the recovery of every IVCf as soon as possible, once they had fulfilled their clinical mission[27]. Only temporary IVCf should be implanted based on the available evidence and routinely removed within 25-54 d according to the guidelines of the USFDA[28].

ENDOVASCULAR TECHNIQUES FOR THE TREATMENT OF MASSIVE PE

The first objective in a massive PE is to remove the artery obstruction in order to reduce pulmonary hypertension and RV failure. Endovascular treatment by different devices of fragmentation or thrombectomy can help reduce the thrombotic load and improve the reperfusion of the vascular system. At the same time, thrombus fragmentation exposes a larger surface area of clot, producing a superior efficacy of the fibrinolytic therapy (Figure 1)[29].

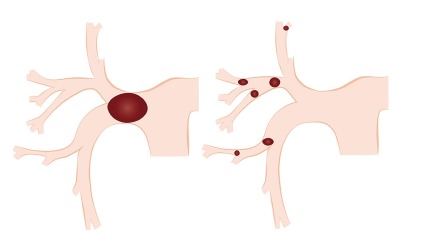

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of thrombus fragmentation by a mechanical thrombolysis resulting a distal embolization of smaller thrombi, creating a larger surface area of the clot improving the efficacy of the thrombolytic agent therapy.

Systemic fibrinolytic therapy has demonstrated to flow in other continuous patent vessels without acting directly into the clogged vessel. Some studies have shown a more precise action of these drugs when it was administered directly within the thrombus with excellent results[30]. Several devices have been used to perform a CDT with different levels of efficacy[12,29,31-41].

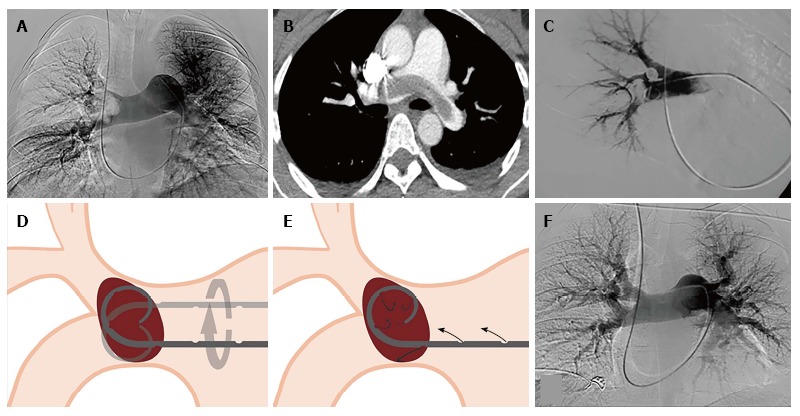

The simplest and most widespread technique is the use of pigtail catheters to fragment the thrombus by continuous rotation of the catheter[42]. The proximal fragmentation of the thrombus leads to distal embolization of smaller thrombi (Figure 1), however some authors have reported pulmonary hypertension with the use of this technique[43]; other authors or many years had shown the contrary[8,34,44,45]. Other devices like balloon catheters of different sizes are inflated and deflated successively for the fragmentation of the thrombi. The aspiration of thrombi located in the pulmonary arteries can also be attempted with aspiration of large caliber catheters (8 French or more)[14]. All of them are used in combination with locally administered fibrinolytic agents through an intra-thrombus catheter. The great advantage of these devices although of dubious effectiveness, is that they are simple to use and available at a low price (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The great advantage of these devices although of dubious effectiveness, is that they are simple to use and available at a low price. A, B: Pulmonary angiography and CT angiography, of a 37-year-old male patient diagnosed with a massive pulmonary embolism; C: Catheter drug therapy, and mechanical thrombolysis; D, E: Schematic representation of mechanical thrombolysis and the infusion of fibrinolytic agents through the pigtail catheter; F: Pulmonary angiography after 24 h of perfusion with 100000.00 UI/h of urokinase, showing no residual occlusion.

The mechanical devices of thrombectomy or endovascular aspiration can be classified by their mechanism of action in: Rheolytic, rotational, aspiration and fragmentation (Table 3)[39].

Table 3.

Fragmentation and aspiration devices used in the endovascular treatment of pulmonary embolism

| Endovascular mechanisms of thrombectomy and thrombolysis | Rheolytic | Rotational | Aspiration | Fragmentation | Ultrasound |

| Devices | Angio Jet | Rotarex | Indigo | Fogarty arterial balloon embolectomy catheter | Ekos Sonic |

| Boston Scientific | Aspirex | Penumbra | Edwards | BTG | |

| Straub Medical | |||||

| Hydrolyzer | Pig-tail Catheter | ||||

| Cordis | Cook Medical | ||||

| Mechanism | Pressurized saline or fibrinolytic agent injection through the catheter in the distal tip, and the remaining fragmented thrombus is aspirated | High-speed rotation coil within the catheter, creating a negative pressure and aspiration of the thrombus | Aspiration pump that provides a high negative pressure of suction with a guide-wire (separator) to create fragmentation of the thrombus | Performing balloon sweeps or manually rotation of the standard Pig-tail to fragment the thrombus | Ultrasound emitting catheter localized within the thrombus to generate an acoustic field creating a more lytic dispersion of the drug infused |

Modified from Barjaktarevic et al[39].

The AngioJet (Boston Scientific Voisins-le-Bretonneux, France) rheolytic system is a thrombectomy designed to aspirate the thrombus using the Venturi-Bernoulli effect. With high-pressure jets and velocity in the distal holes of the system, it creates a zone of low pressure and a suction effect. The system has been associated with multiple complications including bradycardia, blockage, hemoglobinuria, renal insufficiency, severe hemoptysis, even procedural death[29], which the FDA advises against its use as the first therapeutic option in PE[32,46].

The Helix Clot Buster (Medtronic Minneapolis, United States), formerly known as the Amplatz thrombectomy device, is an FDA-approved device for the endovascular treatment to treat dialysis grafts and AV fistulas, but hasn’t been used for thrombectomy in PE. It is a reinforced polyurethane catheter of 7 Fr with lengths from 75 to 120 cm. At its distal end it has a metal impeller that is connected to a motor that rotates more than 140000 rpm, which generates a pressure of 30-35 psi that allows the suction of the thrombus[33].

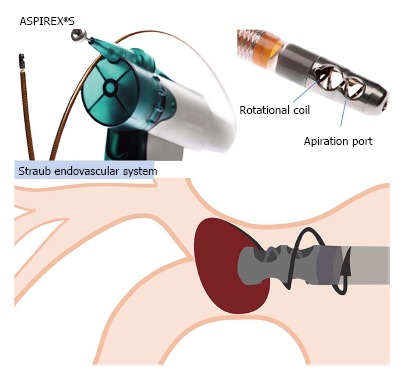

Two relatively new devices are Aspirex and Rotarex (Straub, Wangs, Switzerland). The Aspirex catheter acts as the archimedean screw, that rotates inside the catheter lumen; this spiral mechanism is connected to an active motor producing a thrombus aspiration. A catheter system transports the aspirated material to a manifold. Its clinical results are promising but there are no controlled studies that can support it (Figure 3)[18].

Figure 3.

Aspirex®S by Straub Endovascular System. Mechanism of thrombectomy in which haves a screw that rotates inside the catheter lumen, and this spiral movement is generated by an active motor that produces a thrombus aspiration.

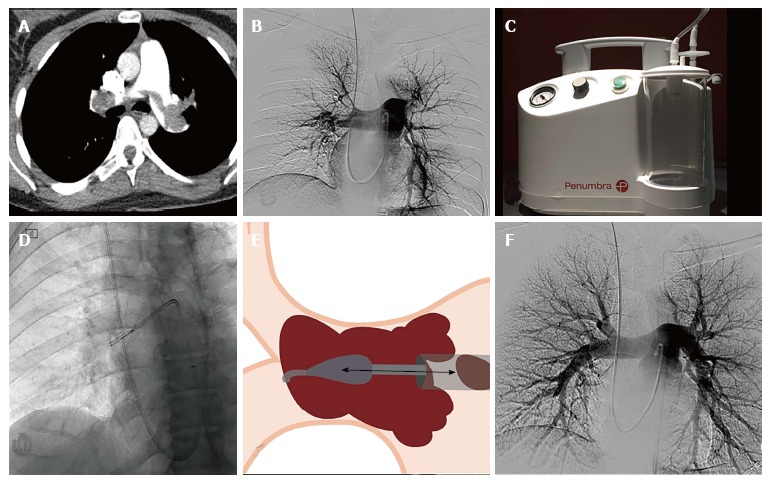

The Indigo mechanical aspiration system (Penumbra Alameda, United States) is an aspiration thrombectomy catheter system. A large caliber (8 Fr) catheter with dirigible and soft tip, allows easy aspiration of the thrombi housed in the pulmonary arteries due to the great suction power of the suction pump. Several studies are being performed to evaluate safety and efficacy of this device (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The Indigo mechanical aspiration system (Penumbra Alameda, United States) is an aspiration thrombectomy catheter system. A, B: Pulmonary angiography and CT angiography, of a 37-year-old male patient diagnosed with a massive pulmonary embolism, 24-year-old female patient diagnosed with massive pulmonary embolism; C-F: Treated with CAT8 and SEP8 Indigo System® by PENUMBRA and catheter directed therapy with Pig-tail catheter with an infusion of 1200000.00 UI urokinase administered in 12 h. CT: Computed tomography.

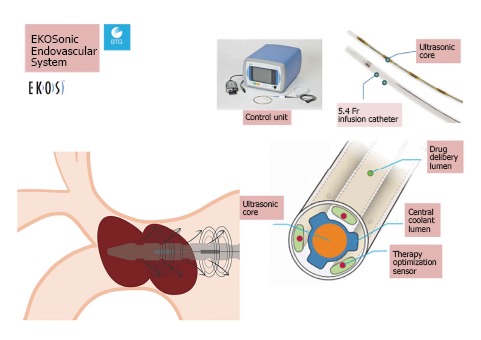

The EKOSonic system (Ekosonic endovascular System BTG Riverside Way, Watchmoor Park, United Kingdom) is the only device approved by the FDA to treat PE. This system generates an acoustic pulse fibrinolytic agent, which have shown satisfactory results to treat massive and submassive PE. The catheter lodges in its interior a sophisticated catheter with an ultrasonic core to effectively target an entire clot. This catheter uses two systems, the ultrasound and the infusion of the fibrinolytic agent. It consists of a 5.4 Fr catheter and has a functional distal tip ranging from 6 to 50 cm in length[41]. However, acoustic field catheters may accelerate dispersion, clinical advantage vs standard infusion catheters is unclear and unproven (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

EKOsonic Endovascular System by BTG. Specialized catheter that lodges in its interior a sophisticated mechanism that haves an ultrasonic core to effectively target an entire clot producing thrombolysis effect, and also helps the infusion of the fibrinolytic agent work faster and more efficient.

RESULTS OF ENDOVASCULAR TECHNIQUES FOR THE TREATMENT OF PE

There are few randomized studies comparing both types of fibrinolytic administration (systemic vs CDT)[47]. The first study on which the ACCP recommendations are based, was published by Verstraete et al[48]. In this study, 34 patients were treated with local or systemic thrombolysis and did not observe significant differences between the two groups in terms of efficacy and complications. It should be noted that in the CDT group, the fibrinolytic agent was administered from the catheter located in a non intra-thrombus approach within the pulmonary artery. The meta-analysis published in 2008 about 35 studies, indicates that 594 patients with PE were treated with CDT and of them 67% received intra-thrombotic thrombolysis during CDT[31]. Treatment with CDT with or without thrombolysis produced a clinical success of 86.5% (356/535). Similar results have now been obtained by combining local fibrinolytic agent with thrombus fragmentation or aspiration[8,49]. PERFECT, a multicenter trial with a total of 101 patients were treated with CDT and achieved a clinical success of 85.7% of the patients diagnosed with massive PE and 97.3% in submassive PE[9]. The use of new devices for fragmentation and/or aspiration of the thrombi can improve these results. The use of ultrasound through a 5.4 Fr catheter with infusion of fibrinolytic leads to rapid lysis of the thrombi located in the pulmonary artery[40,50,51]. Seattle II, a prospective study of 150 patients diagnosed with massive or submassive PE using EKO-sonic and a low dose of r-TPA through CDT, reduced the RV/LV ratio measured with CT by 25% in 48 h, showed a 30% improvement of the systolic pressure and another 30% in the pulmonary artery obstruction[41]. These results, however, according to several authors, do not represent significant differences with those obtained by the standard CDT[49,52].

COMPLICATION

In a randomized study of 1006 patients with submassive PE the risk of intracranial hemorrhage also with systemic thrombolysis is 3%-5% in the various studies[3,53]. Other complications have been described such as: Bradyarrhythmia, cardiac tamponade, rupture or dissection of the pulmonary arteries, severe hemoptysis, renal failure and hemoglobinuria. Major complications (major bleeding and death) ranged from 0%-3%[9,45,49]. A meta-analysis of PE treated with CDT had a 2.4% of major complications and 7.9% of minor complications[29].

CONCLUSION

CDT is an accepted therapeutic technique for the treatment of acute massive PE and cases of submassive PE with RV dysfunction or failure. However it requires a well-trained medical and interventional team to achieve best results. Further clinical studies are needed to analyze the CDT protocol for massive and submassive PE, define which submassive PE patients should be treated with early CDT, and determine if early CDT treatment can decrease the long-term risk of developing chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: Miguel A De Gregorio, Jose A Guirola, Celia Lahuerta, Carolina Serrano, Ana L Figueredo and William T Kuo have no conflicts of interest or financial to disclose related to this review.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: January 19, 2017

First decision: March 27, 2017

Article in press: May 18, 2017

P- Reviewer: Gao BL, Pereira-Vega A, Schoenhagen P, Tawfik MM S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Cushman M, Tsai AW, White RH, Heckbert SR, Rosamond WD, Enright P, Folsom AR. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in two cohorts: the longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology. Am J Med. 2004;117:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen AT, Agnelli G, Anderson FA, Arcelus JI, Bergqvist D, Brecht JG, Greer IA, Heit JA, Hutchinson JL, Kakkar AK, Mottier D, Oger E, Samama MM, Spannagl M; VTE Impact Assessment Group in Europe (VITAE) Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Europe. The number of VTE events and associated morbidity and mortality. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98:756–764. doi: 10.1160/TH07-03-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldhaber SZ, Visani L, De Rosa M. Acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes in the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER) Lancet. 1999;353:1386–1389. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07534-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piazza G, Goldhaber SZ. The acutely decompensated right ventricle: pathways for diagnosis and management. Chest. 2005;128:1836–1852. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudzinski DM, Giri J, Rosenfield K. Interventional Treatment of Pulmonary Embolism. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:e004345. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.116.004345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, Blaivas A, Jimenez D, Bounameaux H, Huisman M, King CS, Morris TA, Sood N, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2016;149:315–352. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emmerich J, Meyer G, Decousus H, Agnelli G. Role of fibrinolysis and interventional therapy for acute venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 2006;96:251–257. doi: 10.1160/TH06-05-0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Gregorio MA, Laborda A, de Blas I, Medrano J, Mainar A, Oribe M. Endovascular treatment of a haemodynamically unstable massive pulmonary embolism using fibrinolysis and fragmentation. Experience with 111 patients in a single centre. Why don’t we follow ACCP recommendations? Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuo WT, Banerjee A, Kim PS, DeMarco FJ, Levy JR, Facchini FR, Unver K, Bertini MJ, Sista AK, Hall MJ, et al. Pulmonary Embolism Response to Fragmentation, Embolectomy, and Catheter Thrombolysis (PERFECT): Initial Results From a Prospective Multicenter Registry. Chest. 2015;148:667–673. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zuin M, Kuo WT, Rigatelli G, Daggubati R, Vassiliev D, Roncon L. Catheter-directed therapy as a first-line treatment strategy in hemodynamically unstable patients with acute pulmonary embolism: Yes or no? Int J Cardiol. 2016;225:14–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.09.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelliccia F, Schiariti M, Terzano C, Keylani AM, D’Agostino DC, Speziale G, Greco C, Gaudio C. Treatment of acute pulmonary embolism: update on newer pharmacologic and interventional strategies. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:410341. doi: 10.1155/2014/410341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Reekers JA, Baarslag HJ, Koolen MG, Van Delden O, van Beek EJ. Mechanical thrombectomy for early treatment of massive pulmonary embolism. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26:246–250. doi: 10.1007/s00270-003-1984-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood KE. Major pulmonary embolism: review of a pathophysiologic approach to the golden hour of hemodynamically significant pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2002;121:877–905. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.3.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuo WT. Endovascular therapy for acute pulmonary embolism. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:167–179.e4; quiz 179. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ten Wolde M, Söhne M, Quak E, Mac Gillavry MR, Büller HR. Prognostic value of echocardiographically assessed right ventricular dysfunction in patients with pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1685–1689. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.15.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piazza G, Goldhaber SZ. Fibrinolysis for acute pulmonary embolism. Vasc Med. 2010;15:419–428. doi: 10.1177/1358863X10380304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furlan A, Aghayev A, Chang CC, Patil A, Jeon KN, Park B, Fetzer DT, Saul M, Roberts MS, Bae KT. Short-term mortality in acute pulmonary embolism: clot burden and signs of right heart dysfunction at CT pulmonary angiography. Radiology. 2012;265:283–293. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12110802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kucher N, Rossi E, De Rosa M, Goldhaber SZ. Prognostic role of echocardiography among patients with acute pulmonary embolism and a systolic arterial pressure of 90 mm Hg or higher. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1777–1781. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.15.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.PIOPED Investigators. Value of the ventilation/perfusion scan in acute pulmonary embolism. Results of the prospective investigation of pulmonary embolism diagnosis (PIOPED) JAMA. 1990;263:2753–2759. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03440200057023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarrett H, Bashir R. Interventional Management of Venous Thromboembolism: State of the Art. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208:891–906. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.17064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The UKEP study: multicentre clinical trial on two local regimens of urokinase in massive pulmonary embolism. The UKEP Study Research Group. Eur Heart J. 1987;8:2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meneveau N, Schiele F, Metz D, Valette B, Attali P, Vuillemenot A, Grollier G, Elaerts J, Mossard JM, Viel JF, et al. Comparative efficacy of a two-hour regimen of streptokinase versus alteplase in acute massive pulmonary embolism: immediate clinical and hemodynamic outcome and one-year follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1057–1063. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meneveau N, Schiele F, Vuillemenot A, Valette B, Grollier G, Bernard Y, Bassand JP. Streptokinase vs alteplase in massive pulmonary embolism. A randomized trial assessing right heart haemodynamics and pulmonary vascular obstruction. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:1141–1148. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Gregorio MA, Gamboa P, Bonilla DL, Sanchez M, Higuera MT, Medrano J, Mainar A, Lostalé F, Laborda A. Retrieval of Gunther Tulip optional vena cava filters 30 days after implantation: a prospective clinical study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:1781–1789. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000244837.46324.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee MJ, Valenti D, de Gregorio MA, Minocha J, Rimon U, Pellerin O. The CIRSE Retrievable IVC Filter Registry: Retrieval Success Rates in Practice. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38:1502–1507. doi: 10.1007/s00270-015-1112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.PREPIC Study Group. Eight-year follow-up of patients with permanent vena cava filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism: the PREPIC (Prevention du Risque d’Embolie Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave) randomized study. Circulation. 2005;112:416–422. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.512834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inferior Vena Cava (IVC) Filters: Initial Communication: Risk of Adverse Events with Long Term Use [Internet] [accessed 2017 May 27] Available from: https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20161023081037/http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm221707.htm.

- 28.Arous EJ, Messina LM. Temporary Inferior Vena Cava Filters: How Do We Move Forward? Chest. 2016;149:1143–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuo WT, Gould MK, Louie JD, Rosenberg JK, Sze DY, Hofmann LV. Catheter-directed therapy for the treatment of massive pulmonary embolism: systematic review and meta-analysis of modern techniques. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:1431–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmitz-Rode T, Kilbinger M, Günther RW. Simulated flow pattern in massive pulmonary embolism: significance for selective intrapulmonary thrombolysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;21:199–204. doi: 10.1007/s002709900244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuo WT, van den Bosch MA, Hofmann LV, Louie JD, Kothary N, Sze DY. Catheter-directed embolectomy, fragmentation, and thrombolysis for the treatment of massive pulmonary embolism after failure of systemic thrombolysis. Chest. 2008;134:250–254. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuo WT, Sze DY, Hofmann LV. Catheter-directed intervention for acute pulmonary embolism: a shining saber. Chest. 2008;133:317–318; author reply 318. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uflacker R, Strange C, Vujic I. Massive pulmonary embolism: preliminary results of treatment with the Amplatz thrombectomy device. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1996;7:519–528. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(96)70793-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fava M, Loyola S, Huete I. Massive pulmonary embolism: treatment with the hydrolyser thrombectomy catheter. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:1159–1164. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siablis D, Karnabatidis D, Katsanos K, Kagadis GC, Zabakis P, Hahalis G. AngioJet rheolytic thrombectomy versus local intrapulmonary thrombolysis in massive pulmonary embolism: a retrospective data analysis. J Endovasc Ther. 2005;12:206–214. doi: 10.1583/04-1378.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshida M, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, Ishihara M, Shimatani Y, Kurisu S, Kusano KF, Ohe T. Novel percutaneous catheter thrombectomy in acute massive pulmonary embolism: rotational bidirectional thrombectomy (ROBOT) Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;68:112–117. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chamsuddin A, Nazzal L, Kang B, Best I, Peters G, Panah S, Martin L, Lewis C, Zeinati C, Ho JW, et al. Catheter-directed thrombolysis with the Endowave system in the treatment of acute massive pulmonary embolism: a retrospective multicenter case series. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:372–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu S, Shi HB, Gu JP, Yang ZQ, Chen L, Lou WS, He X, Zhou WZ, Zhou CG, Zhao LB, et al. Massive pulmonary embolism: treatment with the rotarex thrombectomy system. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34:106–113. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-9878-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barjaktarevic I, Friedman O, Ishak C, Sista AK. Catheter-directed clot fragmentation using the Cleaner™ device in a patient presenting with massive pulmonary embolism. J Radiol Case Rep. 2014;8:30–36. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v8i2.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia MJ. Endovascular Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism Using the Ultrasound-Enhanced EkoSonic System. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2015;32:384–387. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1564707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piazza G, Hohlfelder B, Jaff MR, Ouriel K, Engelhardt TC, Sterling KM, Jones NJ, Gurley JC, Bhatheja R, Kennedy RJ, et al. A Prospective, Single-Arm, Multicenter Trial of Ultrasound-Facilitated, Catheter-Directed, Low-Dose Fibrinolysis for Acute Massive and Submassive Pulmonary Embolism: The SEATTLE II Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1382–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmitz-Rode T, Janssens U, Duda SH, Erley CM, Günther RW. Massive pulmonary embolism: percutaneous emergency treatment by pigtail rotation catheter. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:375–380. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00734-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakazawa K, Tajima H, Murata S, Kumita SI, Yamamoto T, Tanaka K. Catheter fragmentation of acute massive pulmonary thromboembolism: distal embolisation and pulmonary arterial pressure elevation. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:848–854. doi: 10.1259/bjr/93840362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Gregorio MA, Fava M. [Fragmentation and fibrinolysis in pulmonary thromboembolism] Arch Bronconeumol. 2001;37:513. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2896(01)75133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Gregorio MA, Gimeno MJ, Mainar A, Herrera M, Tobio R, Alfonso R, Medrano J, Fava M. Mechanical and enzymatic thrombolysis for massive pulmonary embolism. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:163–169. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61933-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuo WT, Hofmann LV. Drs. Kuo and Hofmann respond. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:1776–1777. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macovei L, Presura RM, Arsenescu Georgescu C. Systemic or local thrombolysis in high-risk pulmonary embolism. Cardiol J. 2015;22:467–474. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2014.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verstraete M, Miller GA, Bounameaux H, Charbonnier B, Colle JP, Lecorf G, Marbet GA, Mombaerts P, Olsson CG. Intravenous and intrapulmonary recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator in the treatment of acute massive pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 1988;77:353–360. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liang NL, Chaer RA, Marone LK, Singh MJ, Makaroun MS, Avgerinos ED. Midterm outcomes of catheter-directed interventions for the treatment of acute pulmonary embolism. Vascular. 2017;25:130–136. doi: 10.1177/1708538116654638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ozmen C, Deniz A, Akilli RE, Deveci OS, Cagliyan CE, Aktas H, Celik Aİ, Akpinar AA, Disel NR, Balli HT, Hanta İ, Demir M, Usal A, Kanadasi M. Ultrasound Accelerated Thrombolysis May Be an Effective and Safe Treatment Modality for Intermediate Risk/Submassive Pulmonary Embolism. Int Heart J. 2016;57:91–95. doi: 10.1536/ihj.15-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teleb M, Porres-Aguilar M, Rivera-Lebron B, Ngamdu KS, Botrus G, Anaya-Ayala JE, Mukherjee D. Ultrasound-Assisted Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis: A Novel and Promising Endovascular Therapeutic Modality for Intermediate-Risk Pulmonary Embolism. Angiology. 2016;68:494–501. doi: 10.1177/0003319716665718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tafur AJ, Shamoun FE, Patel SI, Tafur D, Donna F, Murad MH. Catheter-Directed Treatment of Pulmonary Embolism. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1076029616661414. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fiumara K, Kucher N, Fanikos J, Goldhaber SZ. Predictors of major hemorrhage following fibrinolysis for acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:127–129. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]