Abstract

Background

The number of people with multiple chronic conditions receiving primary care services is growing. To deal with their increasingly complex health care demands, professionals from different disciplines need to collaborate. Interprofessional team (IPT) meetings are becoming more popular. Several studies describe important factors related to conducting IPT meetings, mostly from a professional perspective. However, in the light of patient-centeredness, it is valuable to also explore the patients’ perspective.

Objective

The aim was to explore the patients’ perspectives regarding IPT meetings in primary care.

Methods

A qualitative study with a focus group design was conducted in the Netherlands. Two focus group meetings took place, for which the same patients were invited. The participants, chronically ill patients with experience on interprofessional collaboration, were recruited through the regional patient association. Participants discussed viewpoints, expectations, and concerns regarding IPT meetings in two rounds, using a focus group protocol and selected video-taped vignettes of team meetings. The first meeting focused on conceptualization and identification of themes related to IPT meetings that are important to patients. The second meeting aimed to gain more in-depth knowledge and understanding of the priorities. Discussions were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim, and analyzed by means of content analysis.

Results

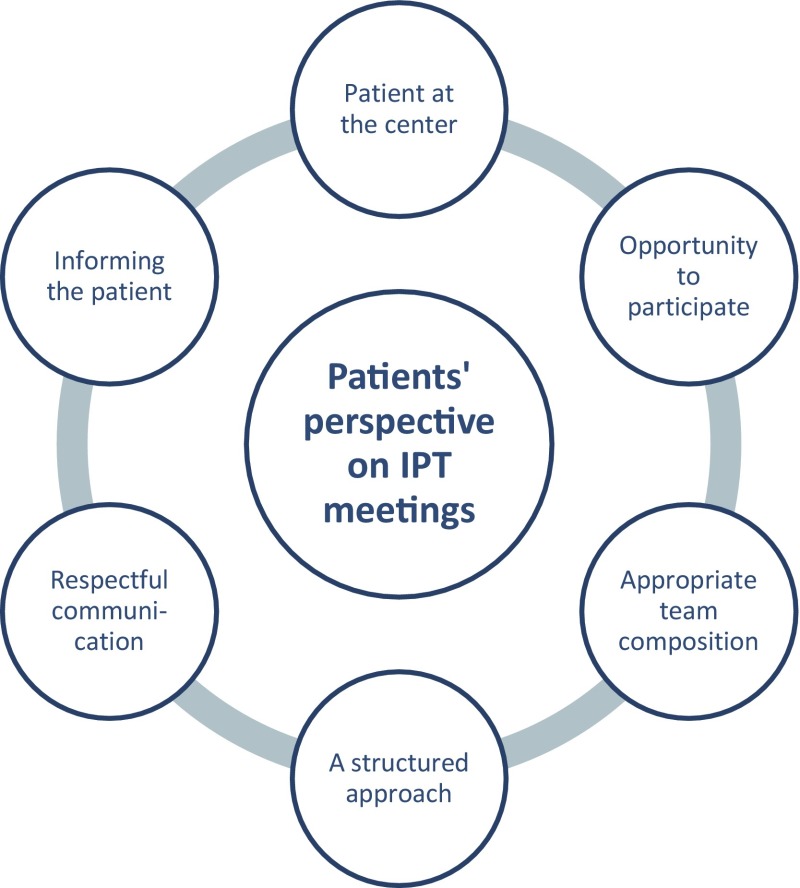

The focus group meetings included seven patients. Findings were divided into six key categories, capturing the factors that patients found important regarding IPT meetings: (1) putting the patient at the center, (2) opportunities for patients to participate, (3) appropriate team composition, (4) structured approach, (5) respectful communication, and (6) informing the patient about meeting outcomes.

Conclusions

Patients identified different elements regarding IPT meetings that are important from their perspective. They emphasized the right of patients or their representatives to take part in IPT meetings. Results of this study can be used to develop tools and programs to improve interprofessional collaboration.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40271-017-0214-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Chronically ill patients appreciate having a voice in their own care process and feeling part of the team. |

| Following the previous key point, patients value the opportunity to participate, or be represented, in interprofessional team (IPT) meetings. |

| Patients expect health care professionals to put the patient at the center and to follow a structured as well as holistic approach to address their needs. |

| Patients want health care professionals to work in a professional manner and communicate respectfully with the ‘patient system’ (comprises the patient and the people representing the patient, such as caregivers, partners, children, or designated health professionals) before, during, and after IPT meetings. |

Introduction

Demographic change is characterized by the rise of the ageing population and its concomitant growing number of people with chronic and often complex conditions [1]. Chronic conditions commonly refer to noninfectious diseases such as type 2 diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or chronic heart failure. To illustrate, 30 % of the population of the EU is suffering from a chronic disease, and the number of people suffering from more than one condition, known as multimorbidity, is increasing [2]. Most of the care for these patients is delivered in the primary care setting, where health care professionals from different disciplines have to deal with increasingly complex and multidimensional health care demands [3, 4]. To comply with this increasing complexity, health care professionals need to work in partnership with each other and the patient system, known as interprofessional collaboration [5]. In a review by Morgan et al., interprofessional collaboration was defined as “An active and ongoing partnership often between people from diverse backgrounds with distinctive professional cultures and possibly representing different organizations or sectors who work together to solve problems or provide services” [6]. Morgan et al. further explain interprofessional collaboration as a deeper level of working together, emphasizing the interaction between team members [6].

Health care professionals increasingly collaborate in interprofessional team (IPT) meetings to ensure communication among and coordination of all professionals involved in patient care. In the Dutch primary care setting, an average IPT consists of family physicians, practice nurses, occupational therapists, physical therapists, district nurses and, in some cases, pharmacists [7]. Conducting IPT meetings has been endorsed by the Department of Health in the UK as the core model for managing chronic diseases [8]. IPT meetings may ensure higher quality decision making and are associated with improved outcomes [3, 9, 10]. During IPT meetings, patients’ care plans are the central topic of discussion. Such care plans can be seen as collaborative and dynamic documents including patients’ goals and actions [11]. However, within current practice, effective and patient-centered teamwork is often lacking [7, 12].

Several studies to explore and improve IPT meetings described key features and influencing factors from the professional perspective [10, 13, 14]; the patients’ perspective on these primary care team meetings seems to be underrepresented in the literature, although we found some data from the field of patient-centered care. Patients seem to value this approach to care, in which they are put at the center as a person [15], and care is focused on their individual needs, facilitating their involvement in care [16]. This last condition is becoming more and more important in the Western world, where patient associations are starting to formulate their own quality indicators for chronic health care. These criteria from a patient perspective comprise aspects like effective care, accessible care, safe care, being in charge of one’s own care process, continuity of care, sufficient information, and transparency about the quality and costs of care [17]. Despite the literature that suggests that the patient’s care plan and need for help should be central during IPT meetings, and that the patient’s role and perspectives are of significant value in refining care processes, there seems to be a lack of literature on patients’ perspective on these IPT meetings [18]. As confirmed by a recent observational study on the effectiveness of multidisciplinary team care [8], exploring the patients’ perspective regarding IPT meetings appears to be a promising approach.

The purpose of this study was to collect qualitative data from patients concerning their views, expectations, and concerns regarding IPT meetings in primary care. These findings are valuable for health care professionals, patient organizations, and policy makers who are responsible for the development of programs and tools to optimize IPT meetings.

Methods

Study Design

We used a qualitative study design and conducted two focus group meetings in December 2015. Our theoretical orientation was based on social constructionism [19], in which social interaction between people leads to the development of knowledge. In this perspective, the main rationale for using focus groups is the production of knowledge through social interaction between all participants, patients as well as members of the research team. The dynamic interaction stimulates the thoughts of participants and reminds them of their own feelings [20]. We assumed that the patient participants were not fully aware of the complexity of the concept of interprofessional collaboration. Therefore, we decided to have two focus groups with the same participants. The first meeting focused on conceptualization by introducing the concept and exploring the views and priorities of the participating patients. The second meeting focused on judgment and included reflexive discussions about the preliminary findings and interpretations. We also assumed that repeated interaction between the same participants leads to more in-depth information [21, 22]. In addition, we expected that repeated interaction would increase the sense of belonging to a group and participants’ sense of cohesiveness [23], which creates a safe climate to share information [24]. Relevant aspects of this study are reported according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research [25].

Research Team

The research team consisted of a range of experts, and comprised five researchers and one patient advocate. JvD is specialized in qualitative research on interprofessional collaboration. MdW is an experienced qualitative researcher and expert on participatory research. He is also an active patient research partner, and moderated both meetings. HS is a qualitative researcher. ES is a patient advocate and staff member at Huis voor de Zorg, a regional umbrella organization of patient organizations in the south of the Netherlands. MvB is a practicing family doctor and senior researcher. RD is a senior researcher (educated as occupational therapist), and mentored the research team.

Study Participants and Recruitment

Participants were selected by means of purposive sampling based on a profile comprising a set of selection criteria (Box 1). Besides the selection criteria, we aimed to obtain a diverse range of patients in terms of sex, age, and health condition. Recruitment was coordinated by the patient organization Huis voor de Zorg. From their network and database, Huis voor de Zorg invited ten people who met our selection criteria (Box 1).

Box 1.

Participant selection criteria

| Experience as a chronically ill patient |

| Experience with interprofessional collaboration |

| Sufficient understanding of the Dutch language |

| Ability to prepare the focus group meeting at home and attend both meetings |

The potential participants received written background information without disclosure of the exact purpose of the focus groups, in order to avoid bias and discourage participants from studying the literature on this topic in advance. Potential participants were invited for both meetings.

Data Collection

Two focus group meetings were conducted in December 2015, and took place in a quiet room at Zuyd University of Applied Sciences (Heerlen, the Netherlands). Each meeting lasted approximately 120 min. During both meetings the moderator (MdW) used a semi-structured interview guide to structure the meeting (see the electronic supplementary material, additional file 1). The discussions were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. After the transcripts had been analyzed by means of content analysis (see Sect. 2.5), one focus group participant (EdB) joined the research team to complement the teams’ interpretation of the results.

Meeting 1

The first focus group meeting was meant to familiarize the participants with the concept of IPT meetings, and focused on the identification of relevant themes related to IPT meetings that were perceived as valuable from the patients’ perspective. In order to stimulate the participants’ understanding and picture of IPT meetings, and provoke discussion, several video fragments of actual IPT meetings in primary care setting were presented. We assumed that showing video fragments would better enable the participants to reflect on issues that matter to them in IPT meetings.

Meeting 2

The second meeting aimed to gain more in-depth knowledge and understanding of the priorities that are important from the perspective of the participants. The meeting started with a member check on the findings of the first meeting: to what extent did they recognize and support the list of elements and categories (or subcategories) that the team had derived from the first meeting? The second part of the meeting comprised a reflexive discussion on relevant facets of IPT meetings, supported by showing several video fragments.

Data Analysis

We applied conventional content analysis to analyze the transcripts [26]. Immediately after the first meeting, an interim analysis was carried out by MdW and HS, who independently analyzed the transcripts and used open coding to abstract meaningful quotes and concepts. Nvivo 10 software was used to organize the data [27]. The two researchers then compared and discussed their codes until consensus was reached, and subsequently grouped the concepts identified into subcategories and broader categories. Disagreements or doubtful codes were discussed by the research team in a face-to-face meeting. Results of the preliminary analysis of the first meeting were used as input for the second meeting. The transcript of the second meeting was analyzed following the same procedure as described above. In the last step, the team came together in another face-to-face meeting, and concluded that the second meeting had provided more in-depth data on the items identified during the first meeting, but had not resulted in new items. The in-depth findings as derived from the second meeting supported a better understanding and simplification of the initial coding as derived from the open coding, and enabled categorization (see the electronic supplementary material, additional file 2). Eventually, the team agreed on a final set of key categories and subcategories.

Trustworthiness

In order to avoid selection bias, Huis voor de Zorg coordinated the recruitment of patients. The researchers’ field notes and written comments were used in the analysis process to enhance the trustworthiness of the study. Furthermore, two researchers coded the data independently and then discussed and compared categories and subcategories. During the preliminary analysis, one of the participants of the study joined and helped in interpreting the research findings by conducting a preliminary member check. An independent qualitative researcher, experienced in moderating focus groups (MdW), and with personal experience with a chronic disease, moderated the focus groups to reduce the researchers’ influence. To increase accuracy, validity, and credibility, we completed a member check [28]. Main findings were sent to all participants, giving them the opportunity to comment on the key findings. To enhance the transferability of the results, we aimed to include the perspectives of patients with a variety of backgrounds and experiences.

Results

Huis voor de Zorg recruited ten patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Eventually, seven of them were able to take part. The remaining three were not able to take part since they were not available on both meeting dates. All participants had personal experience as a patient with a chronic condition, and four participants were taking or had taken care of people with a complex illness. Their characteristics are presented in Table 1. All participants attended both sessions and were involved in the member check.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| N | Gender | Age | Condition | Current occupation | Professional background |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent A | F | 65 | Breast cancer/care-taker | Volunteer/retired | Psychologist |

| Respondent B | F | 55 | Multiple sclerosis | On social benefit | Education |

| Respondent C | F | 62 | Spinal cord injury/osteoarthritis | Volunteer/on social benefit | Child physiotherapist |

| Respondent D | F | 59 | Multiple sclerosis | Volunteer | Caregiver |

| Respondent E | F | 47 | Breast cancer/cardiovascular | Volunteer/on social benefit | Secretary |

| Respondent F | F | 73 | Asthma | Volunteer | Nurse |

| Respondent G | M | 54 | Blind since childhood | Disability pension | Financial specialist |

Analysis of the focus groups resulted in a set of six key features regarding IPT meetings that were important to patients, as presented in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Key features of IPT meetings that are important to patients. IPT interprofessional team

The Patient at the Center

Holistic Approach

Participants emphasized the importance of patient-centered care. During IPT meetings, the health care professionals should focus on the needs of the patient and ensure that the patient’s autonomy is respected as much as possible. There was a broad understanding of the concept of “patients’ needs.” For patients, this concept refers to the notion of well-being and a patient’s role in society, and not merely to physical symptoms and disease-related aspects of care. In response to a video fragment, participants noticed that emotions, cognitive, and social problems were often neglected by health care professionals.

“They did ask me how I was dealing with the chemo, how do you deal with it. But when they told us the bad outcomes, then we were told ‘we will discuss what to do with this at such and such a date. Nothing more, while our world had just fallen apart. Nothing about that.” [A]

For this reason, the participants pleaded for a more holistic approach to health care, highlighting their desire for team members to realize that their patients are more than their diseases or limitations. In addition, more attention should be paid to the psycho-social impact of chronic diseases; patients should be seen in their social context during team meetings, for example, as being part of a family that provides support or, in contrast, is hampering effective solutions. Rather than only the individual patient, the IPT should not forget to assess the entire patient system, including the roles of care-givers, partners, children, or other people representing the patient.

“The IPT takes individual things into account, insulin has to be injected, food and drinks have to be brought, a pacemaker has to be inserted. But comprehensive care for the patient is lacking. And at the end of the day, that’s what patients and their environment need.” [G]

Need for Support

The participants noted that in several video vignettes, no clear definition was presented of the patient’s problem. In some cases, participants saw no need for bringing up the patient’s problem for discussion during the IPT meeting, as the problem could be solved easily by one health care professional or because the issue was too personal and should not be discussed with the entire team. According to participants, an IPT meeting should aim to address the needs for support, preferably formulated or agreed to by the patient or his or her representative.

“If you have a clearly formulated request for support from the patient, it is easier to find the right persons who you need in the IPT.” [E]

According to the participants, the real nature of the patients’ need for support is often unclear, so the IPT meeting does not always result in an appropriate solution for the patient. Participants suggested using a template form or checklist to formulate the request for support to ensure that the meeting remains focused on the patient’s personal interests.

Opportunity for Patients to Participate

In Dutch primary care, it is not routine practice for patients to take part in IPT meetings. Most participants, however, were strongly in favor of giving patients the opportunity to be part of it:

“As a principle, patients have the right to be present when others talk about them.” [C]

They mentioned several benefits. It gives patients the opportunity of free choice and it enhances their own responsibility, as “People will not be speaking about me, but with me.” They mentioned that taking part ensures that the patient’s personal interests will be taken into account, and they expected that IPT members would make clearer decisions about task allocations (who will be doing what) and inform the patient. Although there was consensus on the assumption that patients should be given the opportunity to take part, participants differed in their desire to attend such a meeting. Two participants who did not want to attend such a meeting explained that they trusted the competences of the health care providers and were convinced that they would act in the patients’ best interest. Furthermore, they did not want to put an additional burden on the patient’s shoulders: “Not all patients are able to fulfill this new partnership role.” Patients might not be able to follow the discussion or might not want to hear unpleasant information. As one of the participants said:

“When thrown to the wolves, they can completely clam up.” [B]

The participants identified conditions for participation, in particular, the competences of both patient and health care provider. The patient must be willing to attend the meeting and able to contribute to the discussion. Participants expressed that professionals should prepare patients for their role in the meeting, to clarify mutual expectations. They could introduce the professionals the patient is going to meet and guarantee that all information shared will remain confidential. If the patient is not able to participate in the meeting, a representative could attend instead. If a patient is unwilling or unable to participate, participants found it important that the patient is informed in advance of the meeting and consulted about expectations or preferences. Afterwards, the results and decisions should be appropriately reported to the patient or their representative.

Appropriate Team Composition

Based on several video fragments, participants questioned the efficiency of having many health care professionals around the table, some of whom do not know the patient. They were concerned about the patient’s privacy when intimate information was shared with everyone. Other participants assumed there would be advantages to having unprejudiced experts in the meeting who may represent a different perspective or professional expertise.

“Beforehand, you don’t know what will be discussed. As a psychologist, for example, you may not have a lot of specific input in advance. However, you can think along during the meeting. I think within the multidisciplinary approach it works well to think together, each from his own discipline.” [A]

The participants agreed that all health care professionals around the table should share an interest in the patient’s request for support, should be willing to listen to the patient, and should focus on identifying solutions relevant to the patient’s problem(s). This requires empathy, a competence which is not possessed by all professionals, according to the participants.

The patient participants recognized that implementing integrated care requires professionals to be additionally trained in dealing with patients and their families during IPT meetings. They also agreed that time is an important barrier to improving communication. However, from the perspective of patients, they argued that lack of time may never be a reason for not providing the care that a patient needs.

A Structured Approach to IPT Meetings

Watching the video vignettes, the participants observed that sometimes discussions were very chaotic and lacked a clear structure and coordination. The participants wondered whether the members of the IPT followed a validated approach or methodology:

“I cannot see a common thread, a lot of information was exchanged and an overall picture of the patient was outlined, but in the end, what’s going to actually happen?” [G]

They expected health care professionals to prepare the meeting carefully, to read all information about the patient in advance (including a clear and patient-focused problem definition), and to adhere to an agenda, supervised by a competent chairperson. Participants mentioned the importance of the role of a chairperson who structures the meeting, summarizes, invites others to participate, and guides the team. In the participants’ opinion, the discussions and decisions should be reported in writing and shared with all involved, including deadlines and persons responsible for taking action. According to the respondents, in some of the video vignettes, the team did not make any decisions, nor were tasks or responsibilities assigned to persons. It was not clear to the focus group participants what would be reported to the patient and what problem had actually been solved. They suggested that an IPT meeting should result in a care plan.

Respectful Communication

When watching the video vignettes, some participants observed a lack of respect towards the patient under discussion. They commented that especially in the presence of the patient, it is important for team members to communicate respectfully. For the focus group participants, trust and respectful communication between team members, as well as about the patient, were important requirements in IPT meetings:

“Respect? …the patient is present, but is treated as a case, but not as a human being.” [G]

The participants observed that professionals interrupted each other regularly, avoided eye contact, and did not really listen to each other. According to them, members hardly raised any questions and were sometimes doing other things during meetings, not related to the discussion. According to participants, the professionals should adjust their terminology and explain concepts or procedures if the patient has questions:

“They are speaking in jargon to each other, and I as a patient don’t know all the medical terminology.” [A]

Informing the Patient About Meeting Outcomes

Based on participants’ own experience, they commented that informing the patient after an IPT meeting is often forgotten. Though, participants perceived direct contact before, as well as after the meeting as being important, especially in situations when patients or their representatives are not taking part in the IPT. Participants confirmed that being informed about the outcomes of the meeting is crucial to patients:

“In my opinion the patient has to be informed before the meeting about what the team is going to discuss, and afterwards informed about the outcomes of the meeting.” [C]

At the end of the IPT meeting, those taking part should agree what decisions or agreements need to be shared with the patient. Participants mentioned that some teams have appointed a designated contact person for the patient who ensures that the patients’ needs and preferences are not lost along the way and who is responsible for telling the patients what has been agreed upon. Participants argued that in many cases professionals are still working from the narrow perspective of their own discipline or department. Some participants mentioned the position of a case manager, and indicate that it is his or her task to follow-up on decisions made and to inform the patient, not only orally, but also in writing.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to collect qualitative data from patients regarding their perspective on IPT meetings. Findings were extracted through social interaction between the participants, and can be summarized into six categories: (1) putting the patient at the center, (2) opportunities for patients to participate, (3) appropriate team composition, (4) structured approach, (5) respectful communication, and (6) informing the patient about the outcomes of the meeting.

Many health care professionals subscribe to the value of patient-centeredness, although they give different meanings to the concept in everyday practice [29, 30]. The focus group participants noticed that despite this intention, health care professionals often act within the narrow boundaries of their own specific discipline and often fail to integrate the real-life experiences of patients in their health care. The focus group participants mentioned that the current health care system is still medically oriented, and would like to see those taking part in IPT meetings move towards a more holistic model of illness and disabilities also including social and emotional aspects. In such a model, supporting people to remain active and able to participate in activities that are meaningful to them, including their own care, is just as important as managing the disease and preventing deterioration [31]. A possible strategy to assure patient-centeredness in team meetings is exploring patients’ functioning from a biopsychosocial perspective and supporting patients to formulate personal values, needs, and goals before the meeting, and to focus during the team meeting on how to support patients in achieving those goals [32].

Participation of patients or their representatives in IPT meetings is another way to enhance patient-centered and holistic care [33]. According to the participants, all patients or their representatives should be given the opportunity to participate in IPT meetings if they prefer to do so. The value of taking part in IPT meetings lay in the desire to have a voice in their own care process and thereby preserve one’s autonomy. However, the focus group participants expressed understanding for the fact that not all patients are able or confident enough to raise their voice during an IPT meeting. Children or people with mental or cognitive limitations might be represented by their relatives or caregivers. According to the literature, including the patient or their relatives in a health care team is appreciated by professionals and patients [34], and can be considered a way to stimulate engagement and patient participation [35, 36]. Various studies have shown positive effects of patient participation during IPT meetings and reported that this provided added value in terms of interdependency, communication, and mutual trust [37–39], and increased involvement in decision making [40]. Wittenberg-Lyles et al. reported that hospice teams formulated more patient-centered goals when relatives participated in team meetings [39]. Other studies mentioned barriers to participation like the excessive use of jargon [41, 42] and the potential risk of overburdening the patient [43]. A tailored approach to patient involvement during IPT meetings appears preferable [34]. It seems interesting to explore what it takes to include patients as team members in IPT meetings. According to the participants, the patient should be given the opportunity to have a representative as a stand in for the patient’s interest during IPT meetings, if the patient is not able or willing to attend him- or herself. An alternative option may be to appoint a case manager, i.e., a professional with overall responsibility for the patient’s care [44]. When the case manager’s function includes preparing the meeting by consulting the patient, introducing the patient’s goals and perspective during the meeting, and informing the patient about the outcomes of the meeting, such a case manager could provide added value [44].

Other themes derived from this study are the importance of a structured approach to IPT meetings and respectful communication within the team, in which the chairperson plays a significant role, structuring the meeting and guiding the team. Structured meetings, division of roles (especially the role of a chairperson), and mutual communication are factors that have been found in several studies on influencing factors to the process of interprofessional collaboration [10, 14, 45, 46]. Further, participants also discussed the attendance of professionals and team composition. According to Okun et al., effective health care teams include a mix of people with different talents and capabilities who perform interdependent functions to fulfill the needs of the patients with whom they collaborate [47]. Participants agreed on this, but remarked that this should not lead to an oversized team, since they questioned the effectiveness of having a large team of professionals. Moreover, they emphasized the importance of confidentiality of patient-related information, for which professionals should work in accordance with prevailing laws and regulations. Mutual agreements on organization, working procedures, team composition, roles, and responsibilities, and communication strategy can be considered a useful approach for stimulating cohesion during IPT meetings [48].

The findings of this study were derived in the context of the Dutch health care system, and although we have tried to ensure diversity in the perspectives of the focus group participants, we did not completely succeed in this. We included only one man, no young people, no ethnic minority, and no patient with a mental health problem. Further, most of the participants were active volunteers of various patient organizations, leaving the perspective of vulnerable groups probably underrepresented. However, we did have a mixed group of patients representing a diversity of disease experiences, and we obtained a range of perspectives on the value of IPT meetings. Since IPT meetings are a rather new phenomenon for patients, participants had to master a certain degree of reflectivity and imagination to be included. Hereby we assume a majority of the group (not all) was higher educated, which eventually resulted in a diversity of opinions. As a possible strength, we assume that using video vignettes to illustrate the current IPT meeting practice supported participants in remaining focused on the aim of their discussion.

To our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind to explore the patient perspective regarding IPT meetings in primary care among patients themselves. Professionals and experts recognize the added value of patient participation as well [45]. However, they add external factors relating to professionals’ education, culture, hierarchy, and finance [45]. Since every team has its specific features, reflexivity, the extent to which teams reflect upon their functioning, can be considered the base for all teams to improve [49]. The findings of this study might function as an eye-opener for IPTs, inviting them to self-reflect on patient-centered and holistic care before, during, and after IPT meetings. Within the field of interprofessional care, findings can be used to support further development and implementation of quality improvement programs. Further, education developers can use findings to develop or adapt interprofessional modules.

Conclusion

Patients participating in this study stated that they value the opportunity to be part of IPT meetings, and emphasized the right of the patients or their representatives to attend IPT meetings. More knowledge might be needed about conditions and skills for including patients as team members in IPT meetings. To improve IPT meetings and increase patient-centeredness, promising directions appear to be making someone responsible for respectful communication with the patient system before, during, and after IPT meetings; putting the patient at the center and following a holistic approach in which the patient’s functioning is discussed from a biopsychosocial perspective; and working according to a structured approach. Additional research to explore the effectiveness of these promising directions is needed.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the participants of this study for their contributions to the focus group sessions. In particular, we would like to thank Else de Bont for her contribution to the interpretation of our findings.

Author contributions

JvD, MdW, ES, MvB, and RD contributed to the study design. MdW and JvD moderated the focus group meetings. MdW and HS conducted the preliminary analysis. JvD, MdW, ES, HS, MvB, and RD contributed to data analysis, interpretation of the findings, and writing. All authors approved the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Stichting Innovatie Alliantie (PRO-3-36) and Zuyd University of Applied Sciences.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the writing and content of this article.

Contributor Information

Jerôme Jean Jacques van Dongen, Phone: 0031-(0)45 400 6538, Email: jerome.vandongen@zuyd.nl.

Maarten de Wit, Email: martinusdewit@hotmail.com.

Hester Wilhelmina Henrica Smeets, Email: hester.smeets@zuyd.nl.

Esther Stoffers, Email: esther.stoffers@huisvoordezorg.nl.

Marloes Amantia van Bokhoven, Email: loes.vanbokhoven@maastrichtuniversity.nl.

Ramon Daniëls, Email: ramon.daniels@zuyd.nl.

References

- 1.European Union . EU employment and social situation, quarterly review - March 2013. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2013. pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopman P, et al. Health care utilization of patients with multiple chronic diseases in the Netherlands: differences and underlying factors. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;35:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vyt A. Interprofessional and transdisciplinary teamwork in health care. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(Suppl 1):S106–S109. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pullon S, et al. Observation of interprofessional collaboration in primary care practice: a multiple case study. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(6):787–794. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2016.1220929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodenheimer T, Chen E, Bennett HD. Confronting the growing burden of chronic disease: can the U.S. health care workforce do the job? Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(1):64–74. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan S, Pullon S, McKinlay E. Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: an integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(7):1217–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Dongen JJJ, et al. Interprofessional primary care team meetings: a qualitative approach comparing observations with personal opinions. Fam Pract. 2016 doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmw106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raine R, et al. Improving the effectiveness of multidisciplinary team meetings for patients with chronic diseases: a prospective observational study. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2014;2(37). doi:10.3310/hsdr02370. [PubMed]

- 9.Mickan SM. Evaluating the effectiveness of health care teams. Aust Health Rev. 2005;29(2):211–217. doi: 10.1071/AH050211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Drielen E, et al. Beter multidisciplinair overleg past bij betere zorg [Better multidisciplinary team meetings are linked to better care] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2012;156(45):A4856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newbould J, et al. Experiences of care planning in England: interviews with patients with long term conditions. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimas ID, Renato Lourenco P, Rebelo T. The effects on team emotions and team effectiveness of coaching in interprofessional health and social care teams. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(4):416–422. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2016.1149454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korner M, et al. Interprofessional teamwork and team interventions in chronic care: a systematic review. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(1):15–28. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2015.1051616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nancarrow SA, et al. Ten principles of good interdisciplinary team work. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11:19. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore M. What does patient-centred communication mean in Nepal? Med Educ. 2008;42(1):18–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sumsion T, Lencucha R. Balancing challenges and facilitating factors when implementing client-centered collaboration in a mental health setting. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007;70:513–520. doi: 10.1177/030802260707001203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwaliteit in Zicht, Basisset kwaliteitscriteria: Het patientenperspectief op de zorg voor chronisch zieken (Basic set of quality criteria: the patients’ perspective towards chronic care). Kwaliteit in Zicht; 2010.

- 18.Cheong LH, Armour CL, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ. Multidisciplinary collaboration in primary care: through the eyes of patients. Aust J Prim Health. 2013;19(3):190–197. doi: 10.1071/PY12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger L, Luckmann T. The social construction of reality. New York: Penguin Books; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holloway I, Wheeler S. Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. p. 351. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong LP. Focus group discussion: a tool for health and medical research. Singapore Med J. 2008;49(3):256–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krueger R, Casey M. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters DA. Improving quality requires consumer input: using focus groups. J Nurs Care Qual. 1993;7(2):34–41. doi: 10.1097/00001786-199301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaughn S, Schumm JS, Sinagub J. Focus group interviews in education and psychology. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mortelmans D. Kwalitatieve analyse met Nvivo. Acco Uitgeverij: Leeuwen; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lincoln M, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epstein RM, Street RL., Jr The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):100–103. doi: 10.1370/afm.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sidani S, Fox M. Patient-centered care: clarification of its specific elements to facilitate interprofessional care. J Interprof Care. 2014;28(2):134–141. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2013.862519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goering S. Rethinking disability: the social model of disability and chronic disease. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015;8(2):134–138. doi: 10.1007/s12178-015-9273-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Dongen JJ, et al. Developing interprofessional care plans in chronic care: a scoping review. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):137. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0535-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Locatelli SM, et al. Provider perspectives on and experiences with engagement of patients and families in implementing patient-centered care. Healthcare (Amst) 2015;3(4):209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Dongen JJ, et al. Successful participation of patients in interprofessional team meetings: a qualitative study. Health Expect. 2016 doi: 10.1111/hex.12511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vahdat S, et al. Patient involvement in health care decision making: a review. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(1):e12454. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.12454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saltz CC, Schaefer T. Interdisciplinary teams in health care: integration of family caregivers. Soc Work Health Care. 1996;22(3):59–70. doi: 10.1300/J010v22n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griffith JC, et al. Family meetings—a qualitative exploration of improving care planning with older people and their families. Age Ageing. 2004;33(6):577–581. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dijkstra A. Family participation in care plan meetings: promoting a collaborative organizational culture in nursing homes. J Gerontol Nurs. 2007;33(4):22–29. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20070401-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wittenberg-Lyles E, et al. Inviting the absent members: examining how caregivers’ participation affects hospice team communication. Palliat Med. 2010;24(2):192–195. doi: 10.1177/0269216309352066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oliver DP, et al. Caregiver evaluation of the ACTIVE intervention: “it was like we were sitting at the table with everyone”. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(4):444–453. doi: 10.1177/1049909113490823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choy ET, et al. A pilot study to evaluate the impact of involving breast cancer patients in the multidisciplinary discussion of their disease and treatment plan. Breast. 2007;16(2):178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donnelly SM, et al. Multiprofessional views on older patients’ participation in care planning meetings in a hospital context. Practice. 2013;25(2):121–138. doi: 10.1080/09503153.2013.786695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van de Bovenkamp HM, Trappenburg MJ, Grit KJ. Patient participation in collective healthcare decision making: the Dutch model. Health Expect. 2010;13(1):73–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bakker M, et al. Need and value of case management in multidisciplinary ALS care: a qualitative study on the perspectives of patients, spousal caregivers and professionals. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2015;16(3–4):180–186. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2014.971811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Dongen JJ, et al. Interprofessional collaboration regarding patients’ care plans in primary care: a focus group study into influential factors. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0456-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xyrichis A, Lowton K. What fosters or prevents interprofessional teamworking in primary and community care? A literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(1):140–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Okun S, Schoenbaum S, Andrews D, Chidambaran P, Chollette V, Gruman J, Leal S, Lown B, Mitchell P, Parry C, Prins W, Ricciardi R, Simon M, Stock R, Strasser D, Webb CE, Wynia M, Henderson D. Patients and health care teams forging effective partnerships. Discussion paper. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2014. http://www.iom.edu/patientsaspartners.

- 48.Mickan SM, Rodger SA. Effective health care teams: a model of six characteristics developed from shared perceptions. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(4):358–370. doi: 10.1080/13561820500165142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Widmer PS, Schippers MS, West MA. Recent developments in reflexivity research: a review. Psychol Everyday Act. 2009;2(2):2–11. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.