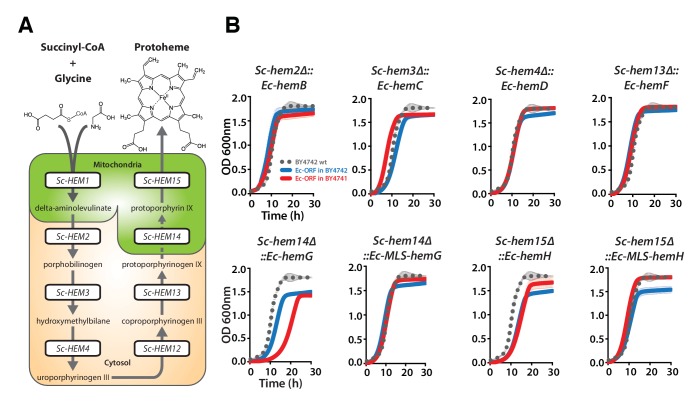

Figure 4. Bacterialization of yeast heme biosynthesis pathway genes at their native loci.

(A) A schematic of the yeast heme pathway shows the beginning of the pathway in mitochondria using succinyl-CoA and glycine as precursors. The subsequent enzymatic reactions are cytosolic up until the penultimate and ultimate reactions which are mitochondrial. (B) Growth kinetics of CRISPR-Cas9 engineered yeast heme pathway genes replaced with the corresponding bacterial genes at their native yeast loci show efficient replaceability in both BY4741 (red solid-line) and BY4742 (blue solid-line) yeast strains. The wild type BY4741 growth curve is shown as a comparison (black dotted-line). Mean and standard deviation plotted with N = 3.