Abstract

Introduction

The process of cardiac calcification bears a resemblance to skeletal bone metabolism and its regulation. Experimental studies suggest that bone mineral density (BMD) and valvular calcification may be reciprocally related, but epidemiologic data are sparse. Methods: We tested the hypothesis that BMD of the total hip and femoral neck measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is inversely associated with prevalence of three echocardiographic measures of cardiac calcification in a cross-sectional analysis of 1,497 older adults from the Cardiovascular Health Study. The adjusted association of BMD with aortic valve calcification (AVC), aortic annular calcification (AAC) and mitral annular calcification (MAC) was assessed with relative risk (RR) regression.

Results

Mean (SD) age was 76.2 (4.8) years; 58% were women. Cardiac calcification was highly prevalent in women and men: AVC, 59.5% and 71.0%; AAC 45.1% and 46.7%; MAC 42.8% and 39.5%, respectively. After limited and full adjustment for potential confounders, no statistically significant associations were detected between continuous BMD at either site and the three measures of calcification. Assessment of WHO BMD categories revealed a significant association between osteoporosis at the total hip and AVC in men (adjusted RR compared with normal BMD=1.24 [1.01–1.53]). In graded sensitivity analyses, there were apparent inverse associations between femoral neck BMD and AVC with stenosis in men, and femoral neck BMD and moderate/severe MAC in women, but these were not significant.

Conclusion

These findings support further investigation of the sex-specific relationships between low BMD and cardiac calcification, and whether processes linking the two could be targeted for therapeutic ends.

Keywords: valvular calcification, osteoporosis, bone, bone mineral density, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Calcification of the fibrous skeleton of the heart is a common aging-related condition associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality.(1–3) Valvular and annular calcification can result in severe impairment of valvular function, requiring surgical or catheter-based valve replacement.(4,5) Despite the similarities of valvular/annular calcification to atherosclerosis,(4,5) there are considerable differences in their pathophysiology,(6) and no medical treatment is currently available to prevent the onset or progression of calcific valve disease, highlighting the need to better understand its pathophysiologic determinants.

Histopathologic studies have shown that valvular and annular calcification exhibit features of bone formation and remodeling, suggesting that such ectopic calcification is closely linked to bone metabolism and its regulation.(7–9) A relationship between bone health and extra-skeletal calcification has been documented in various population-based studies, in which low bone mineral density (BMD) was associated with vascular calcification,(10,11) as well as incident atherosclerotic CVD.(12–14) Yet the extent to which this applies to calcification of the cardiac fibrous skeleton is less clear. Among clinical referral populations, low BMD and osteoporosis were linked to higher prevalence of mitral annular calcification (MAC)(15,16) and aortic valve calcification (AVC),(17,18) but such analyses adjusted only partially for potential confounders. Two population-based studies focusing primarily on middle-aged adults have yielded mixed results. In the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Norfolk cohort, ultrasound-derived calcaneal BMD was inversely associated with first hospitalization for aortic stenosis (AS).(19) By contrast, the Framingham Offspring Study did not detect a significant association between volumetric BMD of the lumbar spine, measured by computed tomography (CT), and either AVC or MAC.(11) Hence, whether BMD exhibits the same reciprocal relationship with calcification of the cardiac fibrous skeleton as demonstrated for vascular calcification remains uncertain.

To our knowledge, no population-based study has examined the relationship between BMD and cardiac calcification with a focus on older adults, the segment of the population most affected by both osteoporosis and calcific valvular and annular disease. The study of older cohorts with high prevalences of these disorders may allow enhanced evaluation of the relevant associations. Nor have hip BMD measures by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), the recommended technique in clinical practice, have not been previously evaluated in relation to valvular or annular calcification in an epidemiologic setting. We sought to bridge these gaps by leveraging availability of DXA measures of BMD of the total hip and femoral neck, as well as systematic echocardiographic assessments of AVC, aortic annular calcification (AAC) and MAC, in the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) to investigate their associations late in life.

METHODS

Study sample

The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) is a prospective investigation of risk factors for CVD in community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older. As detailed previously,(20) participants were identified from Medicare-eligibility lists at four field centers in the U.S. (California, Maryland, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania). Recruitment of an original cohort of 5,201 participants occurred in 1989–90, followed by a supplemental cohort of 697 predominantly African-American individuals in 1992–93. Participants underwent standardized health assessments at each examination comprising medical history, physical examination, blood collection, laboratory measurement, and diagnostic testing, as detailed elsewhere.(21,22)

Of these 5,888 participants, 4,842 took part in the 1994–95 follow-up examination, during which DXA was performed in 2 of the 4 field centers (California and Pennsylvania) for measurement of BMD. Scans were offered to participants in the order in which they presented for examination at the field centers until funding was depleted. Overall, 1,563 participants who underwent DXA and had complete scan data were included in this cross-sectional analysis. Compared with participants who did not have DXA scans, those who did were younger, more frequently white, and healthier, characterized by a more favorable cardiovascular risk profile and lower prevalence of CVD.(23) Among participants with complete DXA data, we excluded 46 participants because of current corticosteroid use, 9 for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, 3 for valvular vegetations, 4 for mitral stenosis of any severity (to allow for a possible rheumatic basis), and 4 for presence of left-sided prosthetic heart valves. Our final study sample included 1,497 participants, of whom 1,427 had available data on AVC, 1,405 on AAC, and 1,453 on MAC.

The CHS Coordinating Center and all field centers received institutional review board approval for the study and participants gave informed consent. The present study was approved by the institutional review board at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Bone mineral density

Participants underwent DXA scanning using the array beam mode QDR 2000 or 2000+ bone densitometers (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA) according to a standardized protocol. All scans were interpreted blindly and monitored for quality control by a core laboratory at the University of California, San Francisco, as previously described.(24) The primary measures of interest were BMD of the total hip and femoral neck, each with a coefficient of variation < 0.75%. Bone mineral density T-scores were calculated in standard fashion based on a reference population of non-Hispanic white women ages 20–29 years.(25) T-scores were categorized as osteoporosis (T-score ≤−2.5), osteopenia or low BMD (−1.0 > T-Score > −2.5) or normal BMD (T-score ≥ −1.0) as per the World Health Organization (WHO) classification. Herein, we use the term osteoporosis (or osteopenia) of the total hip or the femoral neck to specify the location of the abnormally low BMD value, recognizing that such a value at either site suffices to assign a diagnosis of osteoporosis (or osteopenia) to any given individual.

Echocardiographic examination

Standardized echocardiograms were performed at the 1994–95 examination using previously reported methods, with subsequent blinded interpretation at a core laboratory.(26,27) The primary outcome measures were AVC, AAC and MAC. AVC was defined as increased leaflet thickness without restriction of leaflet motion. Aortic stenosis (AS) was defined as thickened leaflets with reduced systolic opening on 2D imaging and/or an increased velocity (>2.0 m/s) across the valve by continuous wave Doppler. AAC was defined as increased echocardiographic density of the aortic root at the insertion of the aortic leaflets. MAC was defined as an echodense structure at the junction of the atrioventricular groove and posterior mitral leaflet and graded as: “mild”, defined as focal, limited increased echodensity of the mitral annulus; “moderate”, defined as marked echodensity involving more than ⅓ but less than ½ of the ring circumference; and “severe”, defined as marked echodensity extending ½ or more of the ring circumference or intruding into the left ventricular inflow tract. Among n=116 randomly selected participants, intra-observer κ scores for AVC and MAC were 0.82 and 0.70, respectively, consistent with substantial agreement; for AAC, intra-observer κ was 0.60, reflecting moderate agreement.

Covariates

A majority of covariates included in this study were collected in the 1994–95 examination. Exceptions included height (for BMI determination), physical activity, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLc), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLc), cystatin C, C-reactive protein and height, which were measured (or, in the case of LDLc, calculated) in 1992–93 and carried forward for analysis. Missing covariate values occurred in a small proportion of participants, ranging from 4.3% and 3.3% for LDLc and HDLc to <1.7% for other covariates. Prevalent diabetes mellitus was defined as treatment with hypoglycemic medications, by fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL or non-fasting glucose ≥200 mg/dL.(28) Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated based on cystatin C concentration.(29) Heavy alcohol use was defined as >7 drinks/week for women and >14 drinks/week for men. Physical activity was measured in kcal/week using previously published methods.(21) Definitions and methods of ascertainment of prevalent CVD (coronary heart disease [CHD], stroke/transient ischemic attack [TIA], heart failure), based on presence of CVD at baseline and adjudication of incident CVD to 1994–95, have been previously reported.(21,30)

Statistical Methods

Analyses were stratified a priori by sex because of differences in prevalence and pathogenic determinants for osteoporosis between men and women.(31) We first examined the associations of continuous BMD at the femoral neck and total hip with AVC, AAC, and MAC. Relationships between femoral neck and total hip BMD and valvular or annular calcification were evaluated separately because of potential differences in their underlying biology. In order to eliminate the influence of extreme values, such values were winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentile of the BMD distributions. We next evaluated WHO categories of BMD to probe potentially non-linear relationships, and to determine the associations for such categories in common use in clinical practice.

Comparison of cohort characteristics by presence or absence of the individual calcification measures was performed with student t, Wilcoxon rank-sum or chi-square test, as appropriate. Multivariable relative risk (RR) regression was used to evaluate the adjusted associations between BMD and cardiac calcification measures. This was implemented via a generalized linear model using a Poisson working model with a log link and robust standard errors. Generalized additive model plots were constructed to assess for linearity of associations between continuous BMD at femoral neck and total hip separately with cardiac calcification measures after accounting for covariates in the fully adjusted model below. In addition to evaluating BMD at the total hip and femoral neck as a continuous variable, we also analyzed these measures in categorical fashion based on clinically applied cutpoints for osteopenia and osteoporosis compared to normal. Sequential multivariable RR regression models were constructed with a priori selection of covariates based on known biology or previously reported associations. Initial adjustment was performed for age and race-ethnicity. In our fully-adjusted model, we additionally included body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive therapy, diabetes mellitus, smoking history (current vs. none, former vs. none), alcohol use, physical activity, estrogen therapy, LDLc, HDLc, eGFR, prevalent CHD, stroke/TIA and heart failure. Sensitivity analyses examined the impact of additional adjustment for lipid- lowering therapy and C-reactive protein. First-order interactions were examined between each measure of calcification and age, sex (after combining both strata), race-ethnicity, eGFR, CHD, stroke/TIA and heart failure.

In secondary analyses, we evaluated the dose-response relationship between continuous BMD and levels of AVC (none, AVC without AS, AVC with AS). Specifically, we used RR regression with the outcome of AVC without AS vs. none, and AVC with AS vs. none. A similar approach was taken in relation to graded levels of MAC (none, mild, moderate/severe).

All analyses were performed with STATA 14.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). A two-tailed p<0.05 was used to define statistical significance without correction for multiple testing.

RESULTS

The mean (SD) age of the study sample was 76.2 (4.8) years, which included 58% women and 19.4% African Americans. Prevalences of cardiac calcification measures in women and men, respectively, were as follows: AVC, 59.5% and 71.0%; AAC 45.1% and 46.7%; MAC 42.8% and 39.5%. AVC with stenosis occurred in 3.7% of women, and 8.4% of men, whereas moderate/severe MAC was present in 3.2% of women and 3.6% of men. Sex-specific cohort characteristics are shown in Table 1 according to cardiac calcification status. In women, all three calcification measures were associated with older age; AVC and MAC were associated positively with LDLc and inversely with estrogen therapy; AAC and MAC were associated with greater prevalent heart failure; and MAC was associated with higher blood pressure and lower eGFR. In men, all three calcification measures were associated with higher CHD prevalence; AAC and MAC were associated with older age and prevalent heart failure; AVC was associated with greater antihypertensive therapy; and MAC was associated with higher LDLc. In both sexes, mean total hip BMD and femoral neck BMD values were numerically lower in those with compared to those without each cardiac calcification measure, but these differences were not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Characteristics* of study cohort by presence or absence of valvular or annular calcification.

| Aortic valve calcification (n=1,427) | Aortic annular calcification (n=1,405) | Mitral annular calcification (n=1,453) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Yes (n=494) | No (n=337) | Yes (n=371) | No (n=451) | Yes (n=362) | No (n=484) |

| Age, years | 76.4 (4.9)§ | 75.1 (4.1)§ | 76.9 (4.8)§ | 75.1 (4.2)§ | 76.8 (5.0)§ | 75.2 (4.1)§ |

| Black race, n (%) | 107 (21.7) | 64 (19.0) | 67 (18.1) | 102 (22.6) | 70 (19.3) | 104 (21.5) |

| Body mass index, m/kg2 | 26.9 (5.0) | 27.2 (4.9) | 26.8 (4.8) | 27.3 (5.0) | 27.2 (5.2) | 27.0 (4.9) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 135 (22) | 133 (19) | 135 (21) | 134 (21) | 138 (21)§ | 132 (20)§ |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 70 (11) | 70 (11) | 70 (11) | 70 (11) | 71 (12)† | 69 (11)† |

| Anti-hypertensive therapy, n (%) | 266 (53.9) | 163 (48.4) | 193 (52.0) | 229 (50.8) | 200 (55.3) | 236 (48.8) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 75 (15.2) | 42 (12.5) | 61 (16.4) | 54 (12.0) | 59 (16.3) | 61 (12.6) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||||

| Never | 250 (51.3) | 184 (54.8) | 196 (53.7) | 236 (52.6) | 182 (50.6) | 258 (54.0) |

| Former | 187 (38.4) | 125 (37.2) | 140 (38.4) | 165 (36.8) | 145 (40.3) | 175 (36.6) |

| Current | 50 (10.3) | 27 (8.0) | 29 (8.0) | 48 (10.7) | 33 (9.2) | 45 (9.4) |

| Alcohol >7 drinks/week, n (%) | 51 (10.3) | 39 (11.6) | 43 (11.6) | 48 (10.6) | 40 (11.1) | 54 (11.2) |

| Physical activity, kcal/week | 878 (270–1950) | 776 (270–1680) | 776 (265–1856) | 867 (270–1828) | 769 (270–1834) | 844 (270–1856) |

| LDLc, mg/dl | 3.47 (0.86)† | 3.34 (0.88)† | 3.45 (0.83) | 3.39 (0.88) | 3.50 (0.88)† | 3.37 (0.86)† |

| HDLc, mg/dl | 1.50 (0.39) | 1.53 (0.39) | 1.50 (0.39) | 1.53 (0.39) | 1.50 (0.39) | 1.53 (0.39) |

| Lipid-lowering therapy, n (%) | 57 (11.5) | 34 (10.1) | 46 (12.4) | 45 (10.0) | 46 (12.7) | 47 (9.7) |

| Estrogen therapy, n (%) | 85 (17.2)‡ | 88 (26.1)‡ | 67 (18.1) | 104 (23.1) | 63 (17.4)† | 111 (22.9)† |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 69 (18) | 71 (17) | 69 (18) | 70 (17) | 67 (18.0)‡ | 71 (17)‡ |

| Prevalent CHD, n (%) | 91 (18.4) | 45 (13.4) | 62 (16.7) | 69 (15.3) | 58 (16.0) | 81 (16.7) |

| Prevalent stroke/TIA, n (%) | 26 (5.3) | 14 (4.2) | 19 (5.1) | 22 (4.9) | 21 (5.8) | 21 (4.3) |

| Prevalent heart failure, n (%) | 20 (4.1) | 12 (3.6) | 23 (6.2)‡ | 9 (2)‡ | 22 (6.1)‡ | 11 (2.3)‡ |

| BMD of total hip, g/cm2 | 0.74 (0.14) | 0.76 (0.15) | 0.74 (0.15) | 0.76 (0.16) | 0.74 (0.14) | 0.76 (0.15) |

| BMD of femoral neck, g/cm2 | 0.64 (0.13) | 0.65 (0.13) | 0.64 (0.12) | 0.65 (0.13) | 0.63 (0.13) | 0.65 (0.13) |

| BMD categories (total hip), n (%) | ||||||

| Normal | 98 (19.8) | 83 (24.6) | 73 (19.7) | 105 (23.3) | 73 (20.2) | 110 (22.7) |

| Osteopenia | 219 (44.3) | 145 (43.0) | 156 (42.1) | 205 (45.5) | 163 (45.0) | 210 (43.4) |

| Osteoporosis | 177 (35.8) | 109 (32.3) | 142 (38.3) | 141 (31.3) | 126 (34.8) | 164 (33.9) |

| BMD categories (femoral neck), n (%) | ||||||

| Normal | 75 (15.2) | 53 (15.7) | 48 (12.9) | 78 (17.3) | 51 (20.2) | 80 (16.5) |

| Osteopenia | 221 (44.7) | 162 (48.1) | 166 (44.7) | 209 (46.3) | 163 (45.0) | 226 (46.7) |

| Osteoporosis | 198 (40.1) | 122 (36.2) | 157 (42.3) | 164 (36.4) | 148 (34.8) | 178 (36.8) |

| Men | Yes (n=423) | No (n=173) | Yes (n=272) | No (n=311) | Yes (n=240) | No (n=367) |

| Age, years | 76.6 (4.8) | 76.7 (5.1) | 77.2 (4.9)‡ | 76.0 (4.7)‡ | 77.3 (5.1)† | 76.2 (4.8)† |

| Black race, n (%) | 73 (17.3) | 32 (18.5) | 37 (13.6)† | 67 (21.5)† | 28 (11.7)‡ | 78 (21.3)‡ |

| Body mass index, m/kg2 | 26.7 (3.6) | 26.3 (3.5) | 26.6 (3.6) | 26.6 (3.6) | 26.5 (3.3) | 26.6 (3.8) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 132 (20) | 129 (20) | 130 (19) | 132 (21) | 132 (21) | 130 (19) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 70 (11) | 69 (10) | 69 (11) | 70 (11) | 69 (11) | 71 (11) |

| Antihypertensive therapy, n (%) | 244 (57.8)‡ | 78 (45.1)‡ | 141 (51.8) | 171 (55.2) | 134 (56.1) | 193 (52.6) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 80 (18.9) | 27 (15.6) | 49 (18.0) | 58 (18.7) | 43 (17.9) | 66 (18.0) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||||

| Never | 129 (30.5) | 57 (33.3) | 84 (44.0) | 99 (31.9) | 75 (31.3) | 113 (31.0) |

| Former | 263 (62.2) | 98 (57.3) | 170 (48.7) | 181 (58.4) | 153 (63.8) | 218 (59.7) |

| Current | 31 (7.3) | 16 (9.4) | 17 (7.2) | 30 (9.7) | 12 (5.0) | 34 (9.3) |

| Alcohol >14 drinks/week, n (%) | 45 (10.6) | 25 (14.5) | 30 (11.0) | 38 (12.2) | 25 (10.4) | 43 (11.7) |

| Physical activity, kcal/week | 1344 (540–2714) | 1215 (454–2733) | 1323 (527–2388) | 1373 (525–3135) | 1175 (480–2880) | 1413 (555–2625) |

| LDLc, mmol/L ** | 3.16 (0.78) | 3.11 (0.78) | 3.19 (0.75) | 3.13 (0.78) | 3.26 (0.78)‡ | 3.08 (0.78)‡ |

| HDLc, mmol/L ** | 1.22 (0.29) | 1.24 (0.31) | 1.22 (0.26) | 1.24 (0.29) | 1.22 (0.26) | 1.22 (0.29) |

| Lipid-lowering therapy, n (%) | 39 (9.2) | 9 (5.2) | 20 (7.4) | 26 (8.4) | 24 (10.0) | 26 (7.1) |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 69 (18) | 68 (16) | 68 (17) | 69 (17) | 67 (18) | 69 (17) |

| Prevalent CHD, n (%) | 145 (34.3)† | 42 (24.3)† | 96 (35.3)† | 85 (27.3)† | 93 (38.8)‡ | 98 (26.7)‡ |

| Prevalent stroke/TIA, n (%) | 43 (10.2) | 15 (8.7) | 24 (8.8) | 31 (10.0) | 31 (12.9) | 30 (8.2) |

| Prevalent heart failure, n (%) | 35 (8.3) | 14 (8.1) | 32 (11.8)‡ | 16 (5.1)‡ | 26 (10.8)† | 22 (6.0)† |

| BMD of total hip, g/cm2 | 0.94 (0.17) | 0.95 (0.17) | 0.94 (0.17) | 0.95 (0.17) | 0.93 (0.16) | 0.95 (0.17) |

| BMD of femoral neck, g/cm2 | 0.78 (0.15) | 0.79 (0.15) | 0.78 (0.14) | 0.79 (0.15) | 0.77 (0.14) | 0.79 (0.15) |

| BMD categories (total hip), n (%) | ||||||

| Normal | 285 (67.4) | 123 (71.1) | 183 (67.3) | 219 (70.4) | 160 (66.7) | 257 (70.0) |

| Osteopenia | 116 (27.4) | 45 (26.0) | 78 (28.7) | 78 (25.1) | 69 (28.8) | 93 (25.3) |

| Osteoporosis | 22 (5.2) | 5 (2.9) | 1 (4.0) | 14 (4.5) | 11 (4.6) | 17 (4.6) |

| BMD categories (femoral neck), n (%) | ||||||

| Normal | 192 (45.4) | 90 (52.0) | 120 (44.1) | 158 (50.8) | 101 (42.1) | 188 (51.2) |

| Osteopenia | 188 (44.4) | 66 (38.2) | 128 (47.1) | 122 (39.2) | 113 (47.1) | 144 (39.2) |

| Osteoporosis | 43 (10.2) | 17 (9.8) | 24 (8.8) | 31 (10.0) | 26 (10.8) | 35 (9.5) |

Presented for continuous variables as mean (SD) or median (interquartile range);

To convert values for cholesterol to milligrams per deciliter, divide by 0.0259;

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

Abbreviations: BMD, bone mineral density; CHD, coronary heart disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDLc, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDLc, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

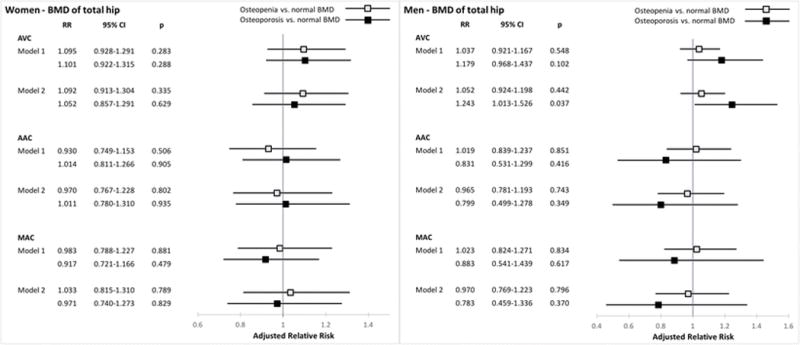

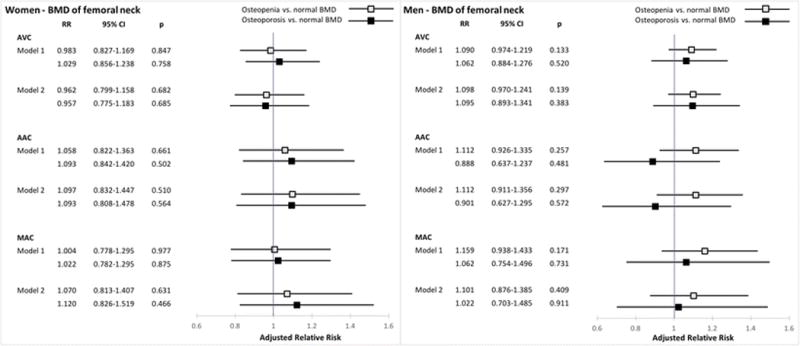

The associations of continuous BMD at the total hip and femoral neck with valvular and annular calcification, stratified by sex, are shown in Table 2. There were no significant associations of total hip or femoral neck BMD with any of the cardiac calcification measures at both levels of adjustment. Generalized additive model plots showed no apparent non-linear associations. Figures 1 and 2 present the sex-specific associations of WHO categories at the total hip and femoral neck, respectively, with cardiac calcification. Minimally and fully adjusted models revealed no significant associations between osteoporosis or osteopenia at either site with any of the calcification measures in the two sexes, with the exception of total hip osteoporosis and AVC in men. As compared with normal BMD of the total hip, osteoporosis at this site was associated with a significant increase of 24.3% [95% CI (confidence interval), 1.3 to 52.6%] in AVC among male participants after full (but not minimal) adjustment for covariates. Additional adjustment for lipid-lowering therapy and C-reactive protein did not meaningfully alter these results. No significant first-order interactions were detected between BMD at either site and age, race/ethnicity, eGFR, and prevalent coronary heart disease, stroke/TIA, or heart failure.

Table 2.

Associations of continuous bone mineral density of total hip and femoral neck stratified by sex.

| Women | Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Hip | ||||||||

| AVC | n | RR* | 95% CI | p | n | RR* | 95% CI | p |

| Model 1 | 831 | 1.024 | 0.979–1.071 | 0.299 | 596 | 1.012 | 0.978–1.046 | 0.506 |

| Model 2 | 784 | 1.003 | 0.952–1.058 | 0.901 | 561 | 1.020 | 0.982–1.060 | 0.309 |

| AAC | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 822 | 0.999 | 0.942–1.060 | 0.979 | 583 | 0.979 | 0.925–1.036 | 0.459 |

| Model 2 | 774 | 0.994 | 0.927–1.066 | 0.871 | 548 | 0.970 | 0.909–1.035 | 0.357 |

| MAC | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 846 | 0.996 | 0.936–1.059 | 0.889 | 607 | 1.014 | 0.951–1.080 | 0.682 |

| Model 2 | 798 | 1.013 | 0.943–1.087 | 0.726 | 570 | 1.008 | 0.939–1.081 | 0.828 |

| Femoral Neck | ||||||||

| AVC | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 831 | 1.019 | 0.968–1.073 | 0.465 | 596 | 1.020 | 0.981–1.062 | 0.320 |

| Model 2 | 784 | 1.000 | 0.942–1.062 | >0.999 | 561 | 1.023 | 0.979–1.070 | 0.307 |

| AAC | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 822 | 1.008 | 0.943–1.079 | 0.809 | 583 | 0.994 | 0.932–1.060 | 0.856 |

| Model 2 | 774 | 1.012 | 0.935–1.095 | 0.766 | 548 | 0.991 | 0.921–1.067 | 0.812 |

| MAC | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 846 | 1.018 | 0.948–1.093 | 0.622 | 607 | 1.026 | 0.954–1.104 | 0.488 |

| Model 2 | 798 | 1.048 | 0.966–1.138 | 0.260 | 570 | 1.029 | 0.951–1.114 | 0.478 |

RR, relative risk per 0.1 g/cm2 decrement in BMD

Model 1. Adjusted for age and race.

Model 2. Adjusted for age, race, BMI, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive therapy, diabetes mellitus, smoking history, alcohol, physical activity, estrogen replacement therapy, LDLc, HDLc, eGFR, prevalent CHD, stroke/TIA and heart failure.

Figure 1.

Associations between WHO categories of bone mineral density at the total hip and cardiac calcification. RR denotes relative risk per 0.1 g/cm2 decrement in BMD

Model 1. Adjusted for age and race.

Model 2. Adjusted for age, race, BMI, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive therapy, diabetes mellitus, smoking history, alcohol, physical activity, estrogen replacement therapy, LDLc, HDLc, eGFR, prevalent CHD, stroke/TIA and heart failure.

Figure 2.

Associations between WHO categories of bone mineral density at the femoral neck and cardiac calcification. RR denotes relative risk per 0.1 g/cm2 decrement in BMD; see Figure 1 legend for model specification.

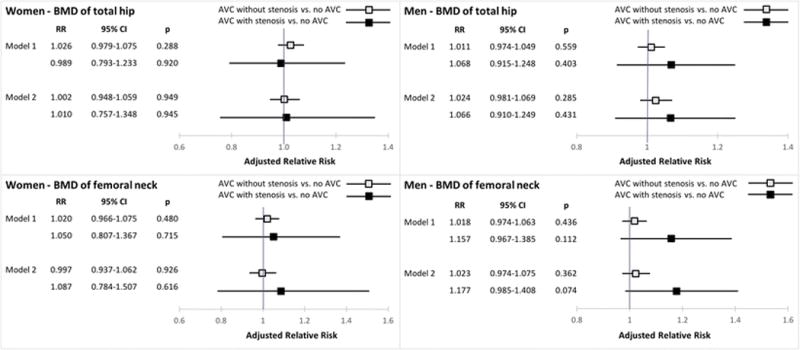

In analyses of graded AVC (Figure 3), there was a possible association in men between continuous femoral neck BMD and AVC with stenosis vs. no AVC that did not reach statistical significance, wherein each 0.1 g/cm2 decrement was associated with a 17.7% (95% CI, −1.5% to 40.8%) higher prevalence of AVC with stenosis after full adjustment. There was no such finding for total hip BMD, however, for which each 0.1 g/cm2 decrement showed a non-significant 6.6% (95% CI, −9.0% to 24.9%) increase of AVC with stenosis. There was no evidence of any association of either BMD measure with graded AVC in women.

Figure 3.

Associations of continuous bone mineral density at the total hip and femoral neck and degrees of aortic valve calcification. RR denotes relative risk per 0.1 g/cm2 decrement in BMD; see Figure 1 legend for model specification.

In the case of graded MAC (Figure 4), there was a marginally non-significant association between femoral neck BMD and moderate/severe MAC in women, wherein each 0.1 g/cm2 decrement was associated with a 66.2% (95% CI −4.5% to 189.1%) higher prevalence of more advanced calcification of the mitral annulus after full adjustment. For total hip BMD, the finding in women was consistent, but less suggestive, with a 33.2% (95% CI, −9.6 to 98.4%) increase in moderate/severe MAC. No apparent associations with moderate/severe MAC were present in men.

Figure 4.

Associations of continuous bone mineral density at the total hip and femoral neck and degrees of mitral annular calcification. RR denotes relative risk per 0.1 g/cm2 decrement in BMD; see Figure 1 legend for model specification.

DISCUSSION

Main Results

The present study in a subset of participants from a prospective cohort study of older adults did not find significant associations between continuous BMD at the total hip and femoral neck measured by DXA and the presence of valvular or annular calcification by echocardiography in either men or women. There was, however, a significant increase in adjusted risk of AVC among men with osteoporosis at the total hip, but not the femoral neck, which was not observed in women. Moreover, in analyses of graded AVC, lower continuous BMD at the femoral neck, but not the total hip, tended to be associated with a higher adjusted risk of AVC with stenosis in men, though not in women, but this did not meet statistical significance. By contrast, there was a tendency for lower continuous BMD at the femoral neck, and less strongly at the total hip, to be associated with higher adjusted risk of moderate or severe MAC in women, a finding that was not apparent in men, although again this failed to reach statistical significance.

Interpretation of Study Findings

The null findings for continuous BMD of the total hip and femoral neck and the presence of any cardiac calcification provide evidence against moderate or stronger cross-sectional associations between BMD at these sites and echocardiographic valvular or annular calcification. But these analyses using concurrent, one-time measures of BMD and any cardiac calcification are likely to underestimate any existing associations, particularly since echocardiography, a technique with imperfect accuracy, was used for cardiac phenotyping. That such cross-sectional analyses do not exclude biologically important associations between BMD and valvular or annular calcification is highlighted by our previous work in this cohort.(32) In the latter, lipoprotein(a) level showed only a 5% adjusted relative risk increase for any AVC by echocardiography, as contrasted with the molecule’s clinically significant causal association with AVC demonstrated in genetic analyses involving CT-determined calcification and clinically advanced AS.(33) Given that the upper limit of the 95% CI’s for continuous BMD herein were often in the range of a 6 to 8% relative risk increase for any AVC, AAC or MAC, meaningful associations of low BMD with cardiac calcification – particularly when the time-dependent impact of dynamic processes potentially linking the two are taken into account – remain possible.

Further, the significant relationship between low BMD and AVC in men noted for the comparison of the osteoporosis with the normal BMD category at the total hip, suggests that the hypothesized association may only have been observable at the extreme of low BMD. Similarly, a borderline non-significant association between continuous low BMD and AVC was present when more advanced AVC, that associated with AS, was examined. The only apparent association observed in women was also in graded analyses, wherein lower continuous BMD showed a marginally non-significant association with moderate or severe MAC. These findings suggest that future longitudinal investigations focusing on more extreme phenotypes, such clinically severe AS, would be better positioned to assess the nature and biological significance of the associations of interest.

In our analyses, osteoporosis based on total hip BMD showed a significant association with AVC in men, but this was not seen for osteoporosis based on femoral neck BMD. This finding could relate to the fact that DXA imaging of the total hip is associated with lower precision error than imaging of the femoral neck, which represents a smaller region of interest subsumed by the total hip measure.(34) However, in the case of the association between continuous BMD and either AVC with AS in men or moderate/severe MAC in women, this proved more suggestive for the femoral neck than the total hip, which is more difficult to explain. In the context of multiple comparisons, the significant association observed, let alone those approaching significance, in analyses of more extreme phenotypes needs to be interpreted with caution given the possibility of chance findings. These associations will require further investigation in larger studies or pooled analyses of existing studies.

Previous Studies

Our findings suggesting sex differences in the relationship of BMD with cardiac calcification measures bear some commonalities with several smaller referral-based studies. In a Japanese investigation, CT-determined BMD of the lumbar spine was inversely associated with echocardiographic MAC, though not AVC, in age-matched analyses among women but not men.(15) A separate study of postmenopausal women who underwent DXA scanning and transthoracic echocardiography showed a significant association between osteoporosis of the lumbar spine and MAC after adjustment for age, although relations with AVC were not reported.(16) Two additional studies(17,18) including patients of both sexes found lower BMD by DXA to be associated with higher frequency of AVC after limited adjustment for covariates, one in women only,(18) but assessment of MAC was not included. Nevertheless, another study comparing calcification and inflammatory processes in bone, heart and vasculature with advanced cardiovascular imaging techniques in a predominantly male sample found no correlation between vertebral body BMD and AVC score by CT, but did not examine MAC.(35)

The results of the present study come in the context of only one previous population-based study to assess BMD in relation to directly measured valvular calcification. In an analysis of the Framingham Offspring Study population in which vertebral and cardiac mineralization were determined by CT in 1318 men and women with a mean age of 60±9 years (range 36 to 83 years), no association was detected between BMD and AVC or MAC.(11) Yet, as compared with our older CHS sample (mean age 76.2 years), the prevalence of valvular calcification in Framingham was a third to a half lower. A separate population-based investigation involving 15,651 men and women 42–82 years of age from the EPIC-Norfolk study documented an association between low BMD measured by ultrasound at the calcaneus and incident AS (defined by ICD-10 code) over mean follow-up of 9.2 years.(19) There were only 122 incident cases, however, and the finding was of borderline statistical significance. No evidence was found for effect modification by sex.(19)

Underlying Mechanisms

Studies in experimental animals and human pathologic specimens suggest that cardiac calcification is closely related to bone metabolism and its regulation. Indeed, valvular and annular calcification exhibit histopathologic features of bone formation and remodeling.(7–9) and have been linked to Vitamin D receptor polymorphisms,(36) parathyroid gene variants,(37) hyperparathyroidism,(38) and serum phosphate levels.(39) Furthermore, inflammation may link the pathophysiology of the skeletal and cardiovascular systems, as pro-inflammatory cytokines acting to promote bone resorption instead act to activate osteogenic programs in vascular and valvular smooth muscle cells and myofibroblasts.(6) A particular exponent of this humoral connection between bone and heart may be the receptor activator for nuclear factor kappa B (RANK) and its ligand (RANKL). Binding of RANKL to RANK on bone osteoclasts results in bone resorption, but similar interaction of the ligand with its receptor on valvular interstitial cells may promote osteoblast activity.(6) In addition, oxidized lipids have been documented as a trigger to inflammation in valve and bone tissue alike, and play a role in the pathogenesis of both osteoporosis and valvular calcification.(40) Hence, various potential mechanisms could underlie the nominally significant and near-significant associations documented here.

In animal models, anti-resorptive therapy with bisphosphonates has been shown to reduce valvular calcification, a finding that was investigated in a population-based observational study.(41) Interestingly, the latter found bisphosphonate use to be directly related to valvular and vascular calcification in younger participants, whereas the association among older participants was inverse, raising the hypothesis that the therapy may have served as a marker of more severe or premature osteoporosis in the younger subgroup and, in contrast, as effective preventive therapy for late-onset and milder osteoporosis in the older subgroup. A second, retrospective propensity-matched observational study did not find significant impact of bisphosphonate therapy on progression of AS.(42) A recent study, however, reported an association of circulating biomarkers of bone turnover to progression of AS severity, specifically in a subset with low 25OH vitamin D levels.(43) A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial currently enrolling patients is examining whether treatment with alendronate and denosumab can reduce or arrest aortic valvular calcification (NCT02132026) in patients with calcific AS.

Although the different associations suggested for men with AVC and women with MAC require independent confirmation, clinical observations make such differences plausible. Osteoporosis is more common in women than men, and may have different risk factors beyond the decline in estrogen that is operative in loss of BMD in post-menopausal women.(31) Although both AVC and MAC have been linked to traditional atherosclerosis risk factors, MAC is more prevalent in women and appears to be strongly related to abnormal calcium-phosphorus metabolism,(32) and chronic kidney disease.(44,45) Consequently, mineral bone disease may be a particularly prominent risk factor for MAC in women. By contrast, as was the case in our sample, men tend to have a greater frequency of atherosclerosis risk factors and prevalent cardiovascular disease, which, as noted, share common risk factors with osteoporosis. It is therefore possible that AVC arising from a greater burden of atherosclerosis risk factors, and dual involvement of these factors in loss of BMD, could be a more dominant determinant of AVC in men.

Limitations

As alluded to earlier, the main limitation of this study is its cross-sectional nature, which makes it impossible to examine the association of bone loss over time with development of valvular calcification. Moreover, because bone loss and valvular calcification are dynamic processes, such cross-sectional assessment would tend to underestimate the cumulative impact of loss of bone mineralization or its underlying mechanisms on calcification of the cardiac valves or annuli. As also suggested above, cardiac calcification was defined by echocardiography, yielding categorical and semi-quantitative endpoints, as compared with CT, which may be a more sensitive and accurate way to determine and grade calcification of the valves and annuli. The greater variability in echocardiographic measures of calcification could account for a reduced ability to detect the associations of interest, particularly for MAC and AAC, for which inter-observer agreement was only moderate. In addition, the present analyses did not adjust for multiple comparisons in order to maximize the ability to detect modest, yet potentially significant, associations measured at a single point in time, and the associations uncovered need to be interpreted in this context.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in this sample from a population-based study of older adults, we did not detect significant associations between continuous BMD at the total hip or femoral neck with cardiac calcification. Yet total hip osteoporosis was associated with increased prevalence of AVC in men, and marginally non-significant associations were observed for lower BMD of the femoral neck and both AVC with AS in men and moderate or severe MAC in women. These findings support additional investigations involving larger cohorts or meta-analysis of available samples to determine whether disruptions to bone homeostasis and valvular calcification are linked and differ by sex, and to assess whether targeting underlying pathways could lead to common approaches to prevention of these important disorders in older adults.

Mini abstract.

Associations between bone mineral density and aortic valvular, aortic annular, and mitral annular calcification were investigated in a cross-sectional analysis of a population-based cohort of 1,497 older adults. Although there was no association between continuous bone mineral density and outcomes, a significant association between osteoporosis and aortic valvular calcification in men was found.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by contracts HHSN268201200036C, HHSN268200800007C, N01HC55222, N01HC85079, N01HC85080, N01HC85081, N01HC85082, N01HC85083, N01HC85086, and grants U01HL080295 and U01HL130114 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Additional support was provided by R01AG023629 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). This work was furthermore supported by NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) Einstein/Montefiore CTSA Grant Number UL1TR001073. A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.chs-nhlbi.org/pi.htm. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Daniele Massera, Shuo Xu, Traci M. Bartz, Anna E. Bortnick, Joachim H. Ix, Michel Chonchol, David S. Owens, Eddy Barasch, Julius M. Gardin, John S. Gottdiener, John R. Robbins, David S. Siscovick and Jorge R. Kizer declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kizer JR, Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, Galloway JM, Welty TK, Lee ET, Best LG, Resnick HE, Roman MJ, Devereux RB. Mitral annular calcification, aortic valve sclerosis, and incident stroke in adults free of clinical cardiovascular disease: the Strong Heart Study. Stroke. 2005 Dec;36(12):2533–7. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000190005.09442.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barasch E, Gottdiener JS, Larsen EKM, Chaves PHM, Newman AB, Manolio TA. Clinical significance of calcification of the fibrous skeleton of the heart and aortosclerosis in community dwelling elderly. The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) Am Heart J. 2006 Jan;151(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barasch E, Gottdiener JS, Marino Larsen EK, Chaves PHM, Newman AB. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in community-dwelling elderly individuals with calcification of the fibrous skeleton of the base of the heart and aortosclerosis (The Cardiovascular Health Study) Am J Cardiol. 2006 May 1;97(9):1281–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindman BR, Clavel M-A, Mathieu P, Iung B, Lancellotti P, Otto CM, Pibarot P. Calcific aortic stenosis. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2016;2:16006. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sud K, Agarwal S, Parashar A, Raza MQ, Patel K, Min D, Rodriguez LL, Krishnaswamy A, Mick SL, Gillinov AM, Tuzcu EM, Kapadia SR. Degenerative mitral stenosis: unmet need for percutaneous interventions. Circulation. 2016 Apr 19;133(16):1594–604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pawade TA, Newby DE, Dweck MR. Calcification in aortic stenosis: the skeleton key. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Aug 4;66(5):561–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohler ER, Gannon F, Reynolds C, Zimmerman R, Keane MG, Kaplan FS. Bone formation and inflammation in cardiac valves. Circulation. 2001 Mar 20;103(11):1522–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.11.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajamannan NM, Subramaniam M, Rickard D, Stock SR, Donovan J, Springett M, Orszulak T, Fullerton DA, Tajik AJ, Bonow RO, Spelsberg T. Human aortic valve calcification is associated with an osteoblast phenotype. Circulation. 2003 May 6;107(17):2181–4. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070591.21548.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arounlangsy P, Sawabe M, Izumiyama N, Koike M. Histopathogenesis of early-stage mitral annular calcification. J Med Dent Sci. 2004 Mar;51(1):35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyder JA, Allison MA, Wong N, Papa A, Lang TF, Sirlin C, Gapstur SM, Ouyang P, Carr JJ, Criqui MH. Association of coronary artery and aortic calcium with lumbar bone density: the MESA Abdominal Aortic Calcium Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009 Jan 15;169(2):186–94. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan JJ, Cupples LA, Kiel DP, O’Donnell CJ, Hoffmann U, Samelson EJ. QCT Volumetric bone mineral density and vascular and valvular calcification: The Framingham Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2015 Oct;30(10):1767–74. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kado DM, Browner WS, Blackwell T, Gore R, Cummings SR. Rate of bone loss is associated with mortality in older women: a prospective study. J Bone Miner Res. 2000 Oct 1;15(10):1974–80. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.10.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samelson EJ, Kiel DP, Broe KE, Zhang Y, Cupples LA, Hannan MT, Wilson PWF, Levy D, Williams SA, Vaccarino V. Metacarpal cortical area and risk of coronary heart disease: The Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004 Mar 15;159(6):589–95. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farhat GN, Newman AB, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Matthews KA, Boudreau R, Schwartz AV, Harris T, Tylavsky F, Visser M, Cauley JA. Health ABC Study The association of bone mineral density measures with incident cardiovascular disease in older adults. Osteoporos Int. 2007 Jul;18(7):999–1008. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugihara N, Matsuzaki M. The influence of severe bone loss on mitral annular calcification in postmenopausal osteoporosis of elderly Japanese women. Jpn Circ J. 1993 Jan;57(1):14–26. doi: 10.1253/jcj.57.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davutoglu V, Yilmaz M, Soydinc S, Celen Z, Turkmen S, Sezen Y, Akcay M, Akdemir I, Aksoy M. Mitral annular calcification is associated with osteoporosis in women. Am Heart J. 2004 Jun;147(6):1113–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aksoy Y, Yagmur C, Tekin GO, Yagmur J, Topal E, Kekilli E, Turhan H, Kosar F, Yetkin E. Aortic valve calcification: association with bone mineral density and cardiovascular risk factors. Coron Artery Dis. 2005 Sep;16(6):379–83. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200509000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi HS, Rhee Y, Hur NW, Chung N, Lee EJ, Lim S-K. Association between low bone mass and aortic valve sclerosis in Koreans. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2009 Dec;71(6):792–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfister R, Michels G, Sharp SJ, Luben R, Wareham NJ, Khaw K-T. Inverse association between bone mineral density and risk of aortic stenosis in men and women in EPIC-Norfolk prospective study. Int J Cardiol. 2015 Jan 15;178:29–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, Furberg CD, Gardin JM, Kronmal RA, Kuller LH, Manolio TA, Mittelmark MB, Newman A. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991 Feb;1(3):263–76. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ives DG, Fitzpatrick AL, Bild DE, Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Crowley PM, Cruise RG, Theroux S. Surveillance and ascertainment of cardiovascular events. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995 Jul;5(4):278–85. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cushman M, Cornell ES, Howard PR, Bovill EG, Tracy RP. Laboratory methods and quality assurance in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Clin Chem. 1995 Feb;41(2):264–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Virtanen JK, Mozaffarian D, Cauley JA, Mukamal KJ, Robbins J, Siscovick DS. Fish consumption, bone mineral density, and risk of hip fracture among older adults: the cardiovascular health study. J Bone Miner Res. 2010 Sep;25(9):1972–9. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robbins J, Hirsch C, Whitmer R, Cauley J, Harris T. The association of bone mineral density and depression in an older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 Jun;49(6):732–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Looker AC, Borrud LG, Hughes JP, Fan B, Shepherd JA, Melton LJ. Lumbar spine and proximal femur bone mineral density, bone mineral content, and bone area: United States, 2005–2008. Vital Health Stat. 2012 Mar;11(251):1–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gardin JM, Wong ND, Bommer W, Klopfenstein HS, Smith VE, Tabatznik B, Siscovick D, Lobodzinski S, Anton-Culver H, Manolio TA. Echocardiographic design of a multicenter investigation of free-living elderly subjects: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1992 Feb;5(1):63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(14)80105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otto CM, Lind BK, Kitzman DW, Gersh BJ, Siscovick DS. Association of aortic-valve sclerosis with cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 1999 Jul 15;341(3):142–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907153410302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2014. Diabetes Care. 2014 Jan;37(Suppl 1):S14–80. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newman DJ, Thakkar H, Edwards RG, Wilkie M, White T, Grubb AO, Price CP. Serum cystatin C measured by automated immunoassay: a more sensitive marker of changes in GFR than serum creatinine. Kidney Int. 1995 Jan;47(1):312–8. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Bild D, Burke GL, Kittner SJ, Mittelmark M, Price TR, Rautaharju PM, Robbins J. Methods of assessing prevalent cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995 Jul;5(4):270–7. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hannan MT, Felson DT, Anderson JJ. Bone mineral density in elderly men and women: results from the Framingham osteoporosis study. J Bone Miner Res. 1992 May;7(5):547–53. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bortnick AE, Bartz TM, Ix JH, Chonchol M, Reiner A, Cushman M, Owens D, Barasch E, Siscovick DS, Gottdiener JS, Kizer JR. Association of inflammatory, lipid and mineral markers with cardiac calcification in older adults. Heart. 2016 Nov 15;102(22):1826–34. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thanassoulis G, Campbell CY, Owens DS, Smith JG, Smith AV, Peloso GM, Kerr KF, Pechlivanis S, Budoff MJ, Harris TB, Malhotra R, O’Brien KD, Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Allison MA, Aspelund T, Criqui MH, Heckbert SR, Hwang S-J, Liu Y, Sjogren M, van der Pals J, Kälsch H, Mühleisen TW, Nöthen MM, Cupples LA, Caslake M, Di Angelantonio E, Danesh J, Rotter JI, Sigurdsson S, Wong Q, Erbel R, Kathiresan S, Melander O, Gudnason V, O’Donnell CJ, Post WS, CHARGE Extracoronary Calcium Working Group Genetic associations with valvular calcification and aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2013 Feb 7;368(6):503–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henzell S, Dhaliwal S, Pontifex R, Gill F, Price R, Retallack R, Prince R. Precision error of fan-beam dual X-ray absorptiometry scans at the spine, hip, and forearm. J Clin Densitom. 2000;3(4):359–64. doi: 10.1385/jcd:3:4:359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dweck MR, Khaw HJ, Sng GKZ, Luo ELC, Baird A, Williams MC, Makiello P, Mirsadraee S, Joshi NV, van Beek EJR, Boon NA, Rudd JHF, Newby DE. Aortic stenosis, atherosclerosis, and skeletal bone: is there a common link with calcification and inflammation? Eur Heart J. 2013 Jun;34(21):1567–74. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ortlepp JR. The vitamin D receptor genotype predisposes to the development of calcific aortic valve stenosis. Heart. 2001;85:635–8. doi: 10.1136/heart.85.6.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmitz F, Ewering S, Zerres K, Klomfass S, Hoffmann R, Ortlepp JR. Parathyroid hormone gene variant and calcific aortic stenosis. J Heart Valve Dis. 2009 May;18(3):262–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iwata S, Walker MD, Di Tullio MR, Hyodo E, Jin Z, Liu R, Sacco RL, Homma S, Silverberg SJ. Aortic valve calcification in mild primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Jan;97(1):132–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Linefsky JP, O’Brien KD, Katz R, de Boer IH, Barasch E, Jenny NS, Siscovick DS, Kestenbaum B. Association of serum phosphate levels with aortic valve sclerosis and annular calcification: the cardiovascular health study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Jul 12;58(3):291–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parhami F, Morrow AD, Balucan J, Leitinger N, Watson AD, Tintut Y, Berliner JA, Demer LL. Lipid oxidation products have opposite effects on calcifying vascular cell and bone cell differentiation. A possible explanation for the paradox of arterial calcification in osteoporotic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997 Apr;17(4):680–7. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.4.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elmariah S, Delaney JAC, O’Brien KD, Budoff MJ, Vogel-Claussen J, Fuster V, Kronmal RA, Halperin JL. Bisphosphonate use and prevalence of valvular and vascular calcification in women: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 Nov 16;56(21):1752–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aksoy O, Cam A, Goel SS, Houghtaling PL, Williams S, Ruiz-Rodriguez E, Menon V, Kapadia SR, Tuzcu EM, Blackstone EH, Griffin BP. Do bisphosphonates slow the progression of aortic stenosis? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 Apr 17;59(16):1452–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hekimian G, Boutten A, Flamant M, Duval X, Dehoux M, Benessiano J, Huart V, Dupré T, Berjeb N, Tubach F, Iung B, Vahanian A, Messika-Zeitoun D. Progression of aortic valve stenosis is associated with bone remodelling and secondary hyperparathyroidism in elderly patients—the COFRASA study. Eur Heart J. 2013 Jul 1;34(25):1915–22. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Umana E, Ahmed W, Alpert MA. Valvular and perivalvular abnormalities in end-stage renal disease. Am J Med Sci. 2003 Apr;325(4):237–42. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200304000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Asselbergs FW, Mozaffarian D, Katz R, Kestenbaum B, Fried LF, Gottdiener JS, Shlipak MG, Siscovick DS. Association of renal function with cardiac calcifications in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009 Mar;24(3):834–40. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]