Abstract

Background

Youth suicide is increasingly being recognized as a major social problem in South Korea. In this study, we aimed to explore the effects of parental support on the relationship between life stress and suicidal ideation among middle-school students.

Methods

This study analyzed data from a cross-sectional study on mental health conducted by the South Korea National Youth Policy Institute between May and July of 2013. Questionnaire responses from 3,007 middle-school students regarding stress factors, thoughts of suicide during the past year, and parental support were analyzed in terms of 3 subscale elements: emotional, academic, and financial support.

Results

Among the participants, 234 male students (7.8%) and 476 female students (15.8%) reported experiencing suicidal ideation in the past year. Life stress significantly influenced suicidal ideation (P<0.001), and parental support and all of the subscale elements had a significant influence on decreasing suicidal ideation. As shown in model 1, life stress increased suicidal ideation (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.318; P<0.001), and, in model 2, the effect of life stress on suicidal ideation decreased with parental support (aOR, 1.238; P<0.001).

Conclusion

Parental support was independently related to a decrease in suicidal ideation, and life stress was independently related to an increase in suicidal ideation. Parental support buffered the relationship between life stress and suicidal ideation.

Keywords: Stress, Psychological; Parent-Child Relations; Suicidal Ideation; Social Support; Adolescent

INTRODUCTION

Suicidal ideation is an urgent mental health problem that can progress to suicide attempts and completed suicide.1) A high prevalence of suicidal ideation is related to high suicide mortality rates. Youth suicide is a major social problem throughout the world in both developed and developing countries.2) Globally, suicide is the second leading cause of death for 15- to 29-year-olds.3) Adolescents attempt suicide at much higher rates than adults do. Among adolescents in the United States, suicide is the third leading cause of death for those aged 10–14 years and the second leading cause of death for those aged 15–34 years.4) Regarding suicidal ideation among 9th- to 12th-grade students in the USA in 2013, 22.4% of female students and 11.6% of male students reported having seriously considered attempting suicide in the last 12 months.

Korea has the highest suicide rate among the 34 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries with nearly 30 deaths per 100,000 people. According to Korea's National Statistical Office data from 2000, suicide is the second leading cause of death in young people, and the number of youth suicide deaths has increased in recent decade.5) In 2009, the leading cause of death for 15- to 24-year-olds was suicide (15.3 people per 100,000), which is 2 times higher than the rate of automobile accidents as a cause of death (8.4 people per 100,000) among 15- to 19-year-olds. Between 2000 and 2010, the suicide death rate among youth doubled from 13.5% to 28.2%.

According to the fourth-stage (2007–2009) National Health and Nutrition Survey of 2,132 adolescents, 317 adolescents (14.9%) reported suicidal ideation, and 17 (0.8%) had attempted suicide.6) The Korean National Evidence-Based Health Care Collaborating Agency's 2009 Online Youth Behavior Survey of 57,009 adolescents found that 10,690 adolescents (18.8%) reported suicidal ideation and 2,376 (4.4%) reported suicide attempts.7,8) The rates of suicide attempts and suicidal ideation were 772 and 3,328 times higher, respectively, than the rate of death from suicide, suggesting that a significant number of adolescents aged 12–18 years consider suicide.

It is important to evaluate the risk factors for adolescent suicide to design interventions that could prevent deaths from suicide.9) However, we cannot effectively prevent youth suicide by modifying a few risk factors under inadequate circumstances. Thus, it is essential to conduct systematic research that identifies the factors leading to suicidal ideation and suicide in youth.

Puberty is a developmental period in which rapid physical, cognitive, and social changes occur in combination with a lack of coping strategies and resources. The brain during adolescence shows distinctive changes and is vulnerable to stressors.10) The proportion of young people who experience mental health problems is relatively high.11) Suicide has been shown to be associated with mental health problems resulting from changes and stress during puberty.12)

Previous research has shown that major life events that cause substantial changes in daily life are associated with adolescents' suicidal behavior.13) However, commonly experienced stress from daily life is also related to suicide.14)

Suicidal ideation is a potential risk factor for future self-injurious behaviors and suicide completion and is an important subject for both researchers and policymakers.15) In isolation, suicidal ideation is not always related to stress because many adolescents who have high levels of stress do not report suicidal ideation. Adolescents who are exposed to major or minor life events related to suicidal ideation may have protective factors or psychological defense mechanisms that mediate stress and prevent suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. One stress-buffering effect is social support from family relationships.16) Despite exposure to multiple stressors, adolescents maintain their lives through social support in the context of supportive relationships with parents, friends, or teachers and other people in their families, schools, or communities.

During adolescence, it is essential for children to maintain a stable attachment to their parents in addition to acquiring independence and autonomy.17) Parents have a major impact on adolescents' development and social adaptation.18)

Parental involvement in the form of ‘at-home good parenting’ has a significant positive effect on children's achievement and adjustment even after all other factors that shape adjustment are removed from the equation.19) In the primary age range, the impact of different levels of parental involvement is much larger than the differences associated with variations in the quality of schools. The scale of this impact is evident across all social classes and ethnic groups.19) Physical and psychological abuse by parents has been reported to increase adolescents' suicide-related behaviors whereas close relationships with parents are related to reductions in youth suicide.20) The number of suicide attempts is high among individuals who have experienced parental divorce or separation and expressions of suicidal ideation, depressive moods, and closed family communication. In addition, individuals who must cope with difficulties alone have a high degree of suicidal ideation.9)

This study explored the numbers of adolescents who experience suicidal ideation and suicide attempts and the way that parental support affects the relationship between life stress and suicidal ideation, specifically as a mechanism for preventing suicide, among middle-school students in Korea.

METHODS

1. Participants

This study analyzed data from a cross-sectional study on mental health promotion for children and youth conducted by the South Korea National Youth Policy Institute between May and July of 2013.

Our population was based on the 2012 Statistical Education Yearbook, which is a nationwide survey of students in the 4th–6th years of elementary school, the 1st–3rd grades of middle school, and the 1st–3rd grades of high school using a stratified multistage colonies sampling technique. A total of 9,402 students, including 3,157 elementary school students, 3,260 middle-school students, and 2,985 high-school students, completed self-questionnaires in their classroom units. We examined the data from 3,260 male and female middle-school students from the 2013 three-year research project. After excluding missing values, we analyzed data from 1,544 male students and 1,463 female students. This study proceeded after a review waiver approval from the institutional review board of Inje University Seoul Paik Hospital (II T-2015-306) .

2. Measurement

The independent variable in this study was life stress. The presence of suicidal ideation was the dependent variable with parental support considered as a mediator of this relationship. The measures, item details, and reliability for the independent, dependent, and mediating variables are described below.

1) Life stress

The life stressors for middle-school students were subdivided into 12 factors: parental relationships, sibling relationships, physical appearance, physical health, psychological health, economic support, friendships, opposite-sex relationships, senior-junior relationships, student-teacher relationships, career, and academic stress. The response categories were coded as ‘never experienced stress’ (1 point), ‘seldom experienced stress’ (2 points), ‘experienced some stress’ (3 points), and ‘experienced much stress’ (4 points). A high score indicated high life stress. The total life stress score was calculated as the equally weighted sum of sub-elements.8)

2) Suicidal ideation

The response categories for the statement, “I have had suicidal ideation in the past year,” were categorized as “yes” or “no.”

3) Parental support

Parental support consisted of emotional, academic, and financial support. The survey included 14 statements: 6 on emotional support, 4 on academic support, and 4 on financial support. The response categories were coded as ‘strongly disagree’ (1 point), ‘disagree’ (2 points), ‘agree’ (3 points), and ‘strongly agree’ (4 points). A high score indicated high parental support. The total parental support score was calculated as the equally weighted sum of sub-elements.8)

The 6 statements on emotional support were, “They give me emotional comfort,” “They know and understand me,” “They show me warmth,” “They listen to my worries,” “They give me help when I encounter hardship,” and “They give me comfort when I feel disappointed or frustrated,” with a Cronbach's α21) of 0.945. The 4 statements on academic support were, “They counsel me on academic problems,” “They give me study advice,” “They give me necessary information and good books,” and “They teach me good study habits and ways of life,” with a Cronbach's α of 0.881. The 4 statements on economic support were, “They give me pocket money,” “They buy me items for studying,” “They buy me school supplies,” and “They allow me to live without financial worries,” with a Cronbach's α of 0.790.

3. Statistical Analysis

The study used PASW SPSS ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for data analysis. All analyses used 2-tailed tests, and a P-value less than 0.05 was statistically significant.

Frequencies were computed to describe the participants' characteristics, and independent-sample t-tests and chi-square tests were used to examine gender and school year differences in suicidal ideation. The relationships between suicidal ideation and sub-elements of life stress or parental support were calculated using logistic regression analysis of each sub-element as an independent variable, one by one, adjusted for sex, grade, area, and employment status of parents. Parametric statistics were used with Likert scales of life stress and parental support, which are ordinary variables.22)

We assumed life stress as an independent variable, suicidal ideation as a dependent variable, and parental support as a mediator variable. We calculated the significance of the relationship between life stress and suicidal ideation and the relationship between life stress and parental support using logistic regression analysis controlling for gender, school year, region, and parents' occupation. Then, we examined whether the relationship between life stress and suicidal ideation with the mediator became smaller in absolute value than the relationship between life stress and suicidal ideation without the mediator using hierarchical logistic regression analysis. We also identified the interaction effect of life stress and parental support using Hosmer and Lemeshow's goodness-of-fit test.

RESULTS

1. Participant Characteristics

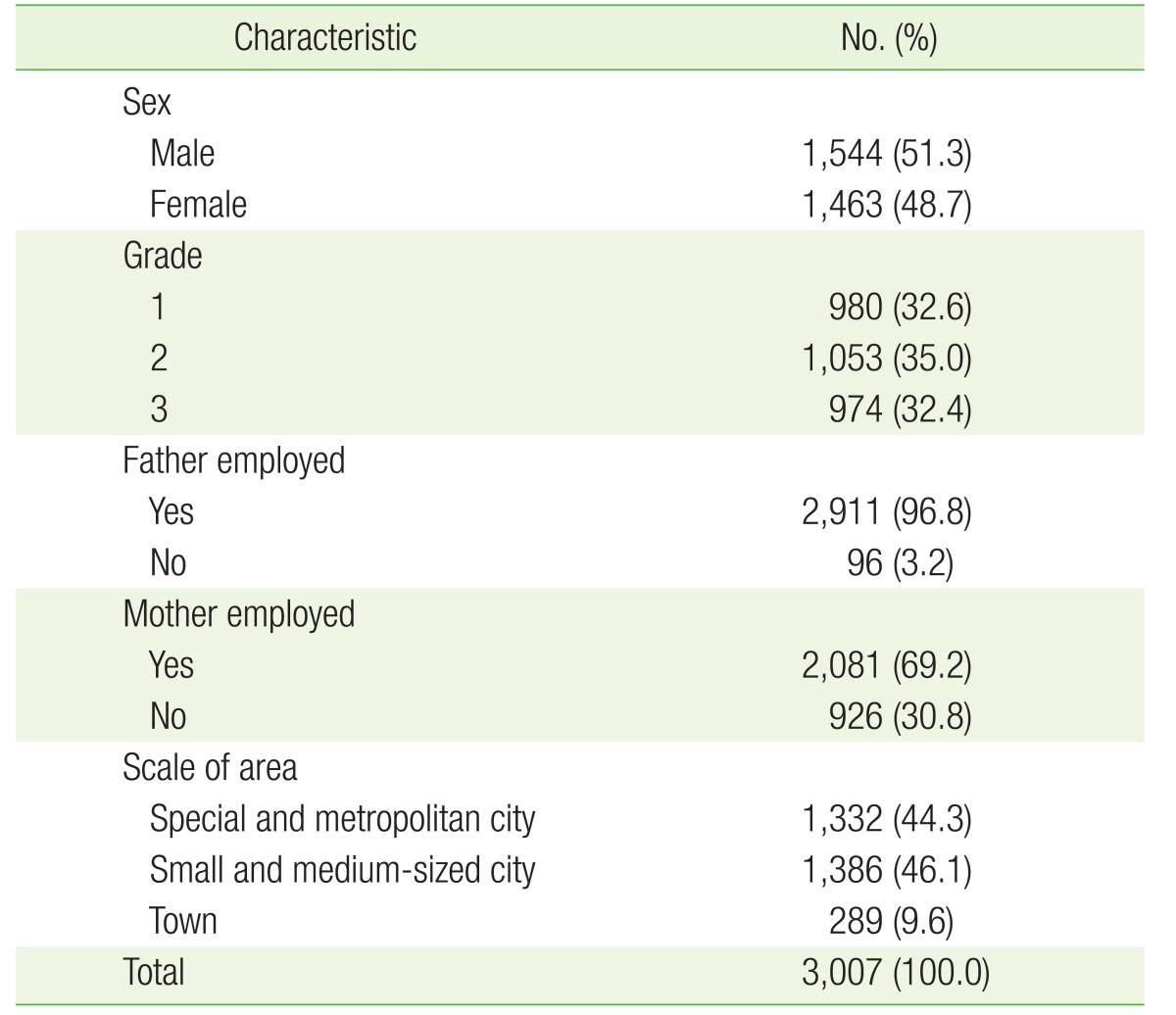

The participants were 3,007 male and female middle-school students who participated in the 2013 South Korea National Youth Policy Institute survey. They included 1,544 male students (51.3%) and 1,463 female students (48.7%) from 16 cities across the country. Of these participants, 2,911 (96.8%) reported that their fathers worked, and 96 (3.2%) reported that their fathers did not work. Furthermore, 2,081 participants (69.2%) responded that their mothers worked whereas 926 (30.8%) responded that their mothers did not work. Of the participants, 1,322 (44.3%) lived in a large metropolitan city, 1,386 lived in a small city (46.1%), and 289 lived in a town (9.6%). Most of the participants were concentrated in special/metropolitan and small cities (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 3,007 middle-school students.

2. Sex and School Year Differences in Suicidal Ideation

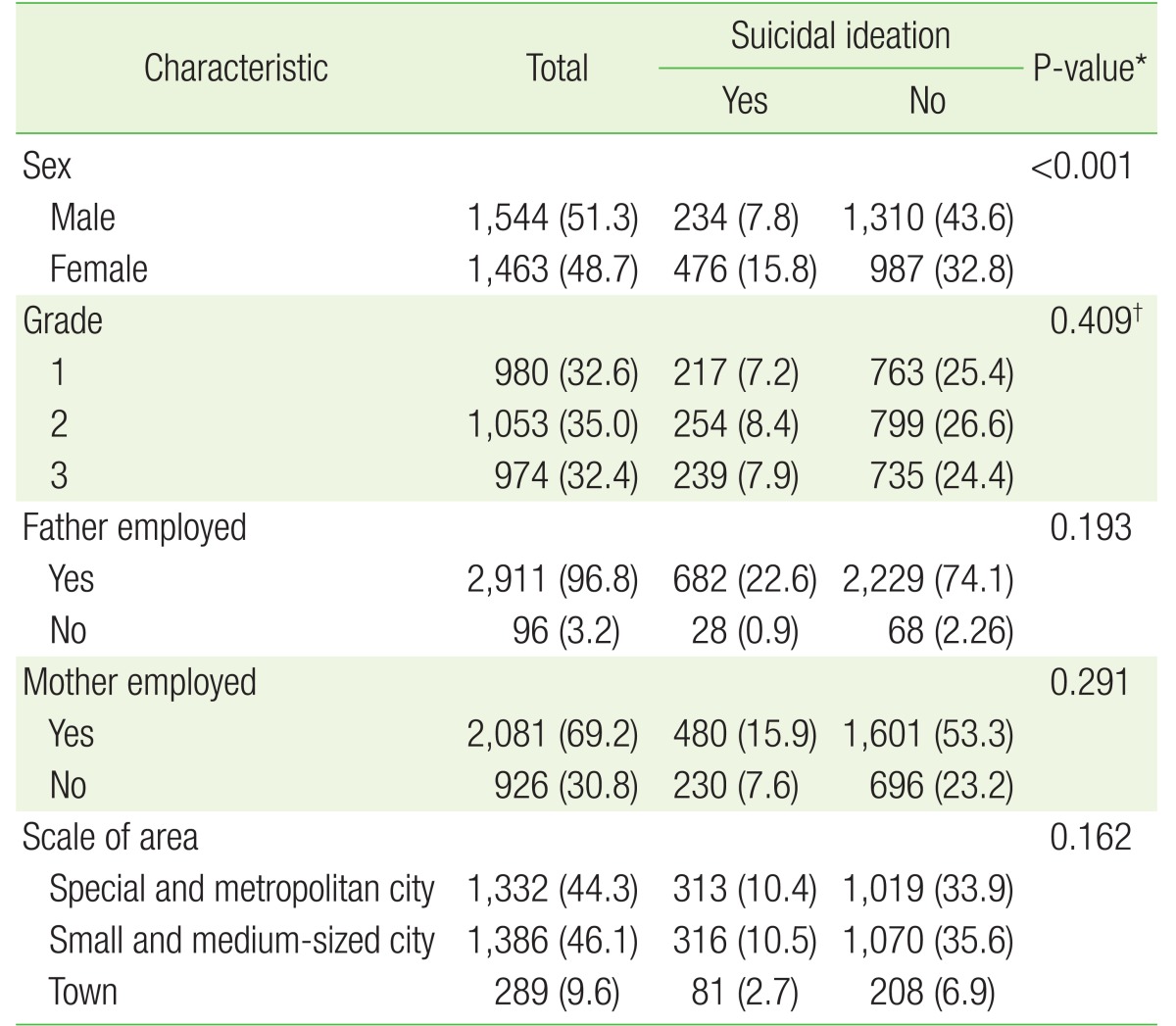

Of the 3,007 participants, 710 (23.6%) responded that they had experienced suicidal ideation in the past year whereas 2,297 (76.4%) reported no suicidal ideation. Of the 710 students asked whether they had experienced suicidal ideation in the past year, 130 (18.3%) responded that they had suicidal ideation within the past year, 569 (80.1%) had not had suicidal ideation, and 11 (1.5%) did not respond. Regarding the differences in suicidal ideation between the sexes, the results showed that 234 male students (7.8%) and 476 female students (15.8%) reported suicidal ideation in the past year. The difference between male and female students with regard to suicidal ideation was significant (P<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Suicidal ideation according to sex and grade.

Values are presented as prevalence (%).

*By chi-square test. †P for trend.

In terms of the year in school, 217 students in the first year (7.2%), 254 in the second year (8.4%), and 239 in the third year (7.9%) reported experiencing suicidal ideation in the past year. However, there were no significant differences in the occurrence of suicidal ideation across school years (P=0.212).

3. Differences in Suicidal Ideation by Life Stress and Parental Support

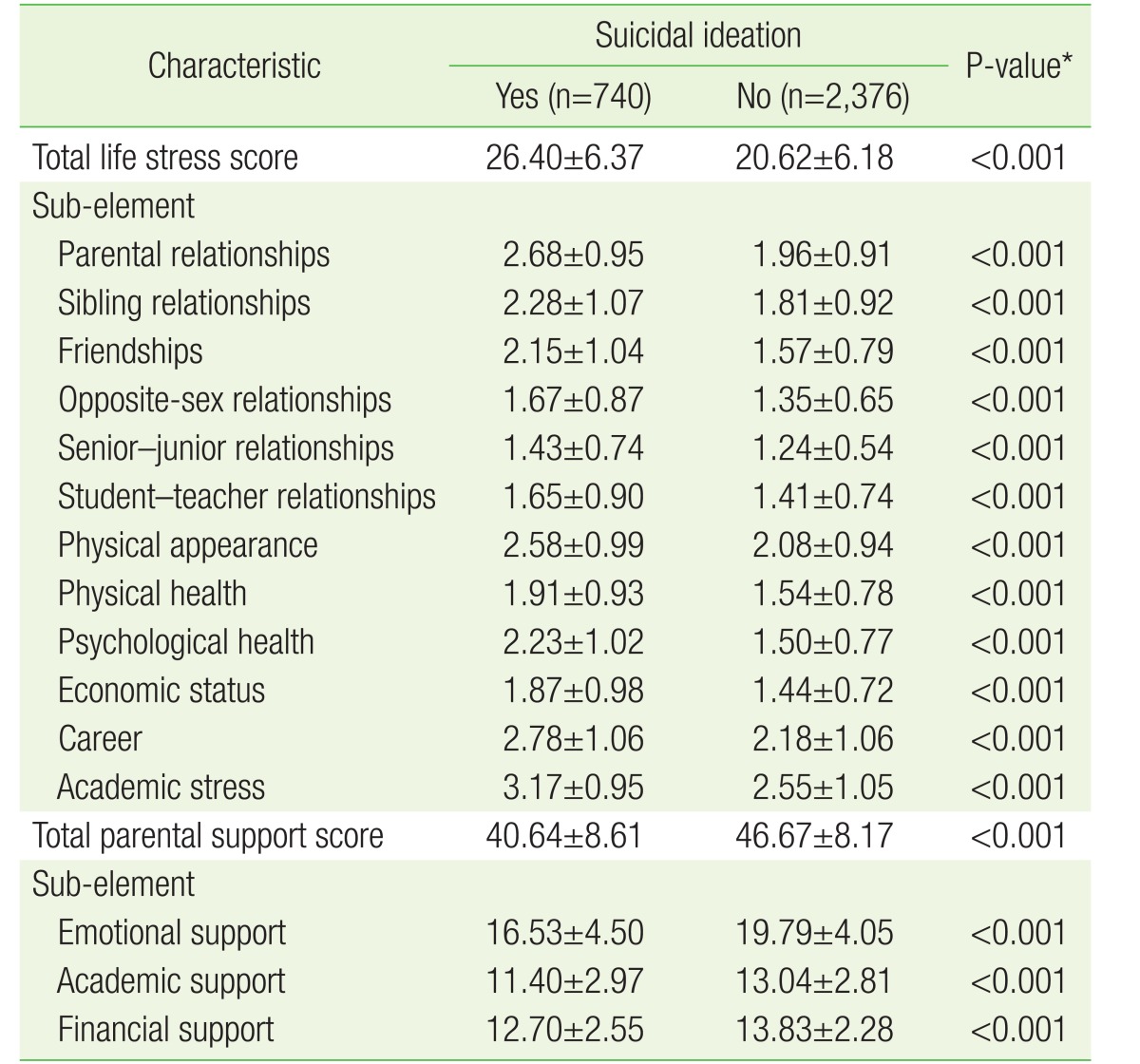

Life stress included 12 factors: parental relationships, sibling relationships, physical appearance, physical health, psychological health, economic status, friendships, opposite-sex relationships, senior-junior relationships, student-teacher relationships, career, and academic stress. The responses were coded as ‘never experienced stress’ (1 point), ‘seldom experienced stress’ (2 points), ‘experienced some stress’ (3 points), and ‘experienced much stress’ (4 points) (Table 3).

Table 3. Suicidal ideation according to life stress and parental support as total and sub-element scores.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation.

*By t-test.

The total overall life stress scores, which included the scores for the 12 sub-elements, ranged from 12 to 48 points. The participants who reported having had suicidal ideation in the past year had an overall life stress score of 26.40 (standard deviation [SD]=6.37), which was significantly higher than the score of the participants who did not report experiencing suicidal ideation of 20.62 (SD=6.18) (P<0.001).

Regarding the sub-elements of life stress and suicidal ideation, the participants who reported having had suicidal ideation in the past year had a higher stress score than those who did not report suicidal ideation for all 12 factors (P<0.001).

Parental support consisted of emotional, academic, and financial support and was measured with responses to 14 statements: 6 on emotional support, 4 on academic support, and 4 on financial support. The students' responses were recorded on a 4-point scale that included ‘strongly disagree’ (1 point), ‘disagree’ (2 points), ‘agree’ (3 points), and ‘strongly agree’ (4 points).

The overall parental support scores were based on the sum of the responses to the 14 sub-support statements and ranged from 14 to 56. The participants who had experienced suicidal ideation scored 40.64 (SD=8.61), and the participants who did not report suicidal ideation scored 46.67 (SD=8.17). The influence of parental support on suicidal ideation was significant (P<0.001).

Regarding the sub-elements of parental support and suicidal ideation, the participants who reported having had suicidal ideation in the past year had a higher stress score in all 3 factors than those who did not report suicidal ideation (P<0.001).

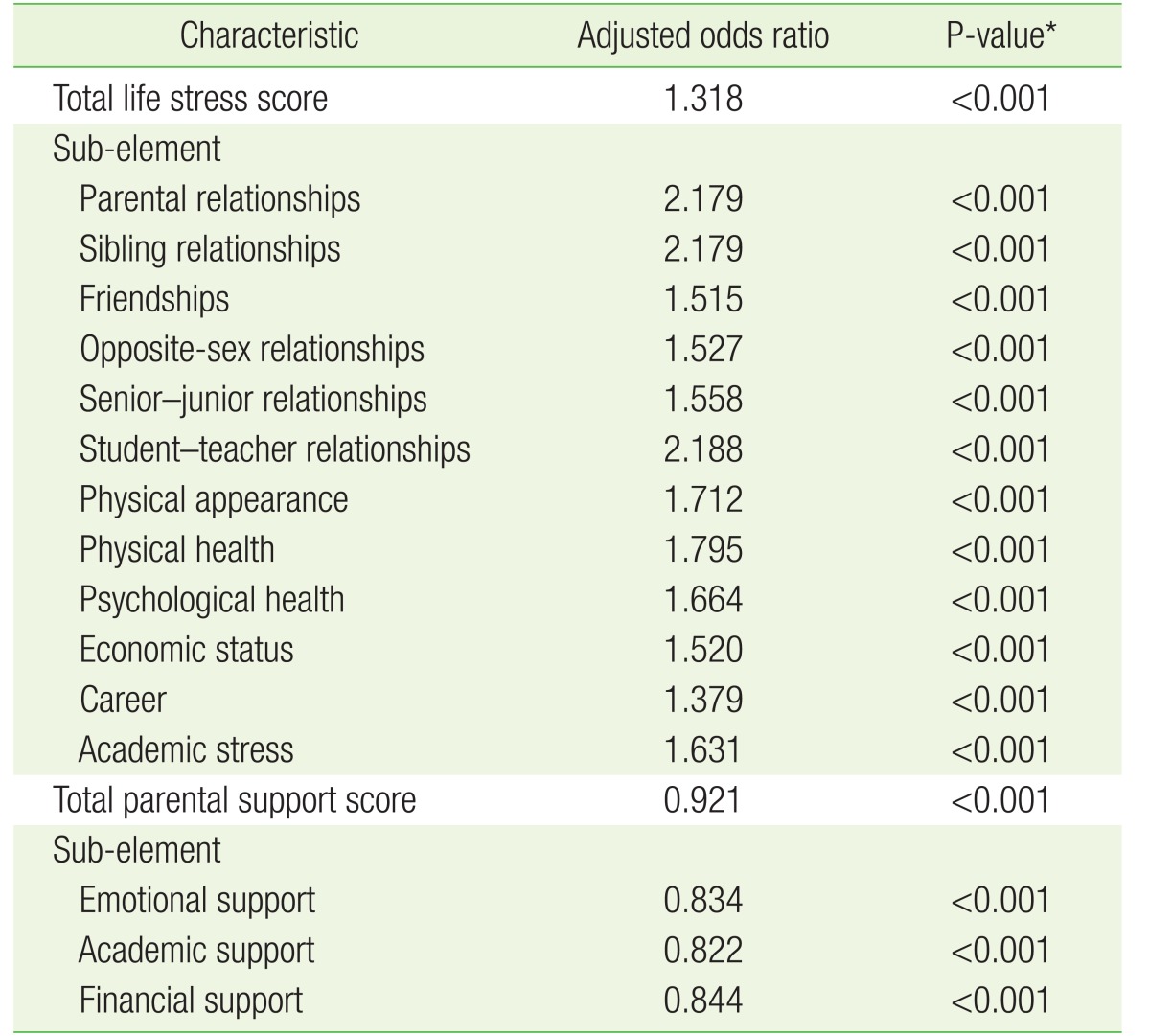

4. The Influence of Life Stress and Parental Support on Suicidal Ideation

The effect of life stress as a sub-element and a total score created by summing the sub-element scores was examined using logistic regression analysis, adjusting for sex, grade, area, and parental employment status. The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) between life stress as a total and the presence of life stress was 1.316 (P<0.001). Among the 12 sub-elements, life stress associated with relationships with parents, siblings, and teachers increased the risk of the presence of suicidal ideation more than other factors (Table 4).

Table 4. Adjusted odds ratios of suicidal ideation according to life stress and parental support total and sub-element scores.

*By logistic regression analysis regarding each sub-element as an independent variable adjusted for sex, grade, area, and employment status of parents.

The influence of parental support as a sub-element and a total score created by summing the sub-element scores was also examined. The adjusted OR of parental support as a total score was 0.921 (P<0.001). For the 3 subdomains of parental support, the aORs of emotional, academic, and financial support were 0.834, 0,822, and 0.844 (P<0.001), respectively, indicating that parental support reduced the risk of the presence of suicidal ideation.

5. The Mediating Effect of Parental Support on the Relationship between Life Stress and Suicidal Ideation

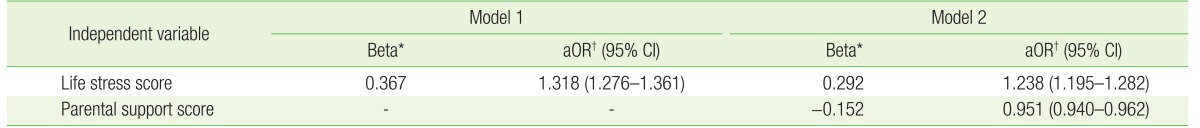

A hierarchical regression analysis evaluated the mediating effect of parental support on the relationship between middle-school students' life stress and suicidal ideation over the past year. The independent variable was life stress, the dependent variable was suicidal ideation, and the mediator was parental support. The results of this analysis are shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Mediating effect of parental support on the relationship between life stress and presence of suicidal ideation.

P-value of interaction term between total life stress score and total parental support score was 0.214.

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

*Standardized coefficients. †By hierarchical logistic regression analysis adjusted for sex, grade, area, and employment status of parents.

The total explanatory power for the mediating effect model was 13.4% for model 1, which included life stress and suicidal ideation, and 15.1% for model 2, which examined the influence of parental support on life stress and suicidal ideation. Both models were statistically significant (P<0.001). The Durbin-Watson value was 1.89, and there was no autocorrelation between the variables.

For models 1 and 2, life stress had a significant relationship with suicidal ideation (model 1: standardized coefficient beta=0.367, aOR=1.318, P<0.001; model 2: standardized coefficient beta=0.292, aOR=1.238, P<0.001); hence, life stress was associated with increased suicidal ideation.

In model 2, the standardized coefficient beta value decreased suicidal ideation based on parental support. Parental support was negatively related to suicidal ideation; therefore, it decreased suicidal ideation (model 2: standardized coefficient beta=−0.152, aOR=0.951, P<0.001). The interaction effect between life stress and parental support was not statistically significant (P=0.214).

When examining parental support as a mediator of the relationship between life stress and suicidal ideation, the R2 value increased slightly from 13.4% for model 1 to 15.1% for model 2. The F-value's P-value was <0.001. Therefore, parental support mediated the relationship between life stress and suicidal ideation.

DISCUSSION

This study found a high prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts and small but significant mediating effects of parental support on the relationships between life stress and suicidal ideation among middle-school students in Korea.

In terms of gender differences in suicidal thoughts, girls reported more suicidal ideation than boys did. The higher rate of suicide ideation among female students is consistent with previous studies.23) There was no statistically significant difference in suicidal ideation across the 3 middle-school grades.

In terms of sources of stress, all sub-scales, including relationships with parents, brothers and sisters, friends, seniors-juniors, and teachers as well as physical appearance, physical health, psychological health, economic condition, and career, were related to suicidal thoughts. Consistent with prior research, this finding indicates that poor relationships with parents and a lack of interaction with peers in adolescence may lead to suicidal ideation.24) These results are similar to those of a study that found that interpersonal conflict is a potential mechanism that may increase the likelihood of suicide attempts through attachment insecurity.2,25) The parental support subscales (emotional, academic, and economic support) were also related to reduced suicidal thoughts. This result is consistent with previous research that found that parents play an important role in the lives of adolescents who have suicidal thoughts and behaviors.26) The role of the family in preventing suicidal behavior is important.27) Fostering cohesion, familial support, and attachment security in the family may lead to positive outcomes for adolescents struggling with suicidal ideation.28) In addition, adolescents who attempt suicide experience high stress within their families, and their families have very limited problem-solving and coping skills.29)

In addition to exploring life stress and parental support as risk factors for suicidal ideation, we examined parental support as a mediator that may decrease the relationship between life stress and suicidal thoughts. Parental support significantly decreased suicidal ideation for children who experienced high levels of life stress. This finding suggests that parent-family connectedness is a protective factor against attempting suicide, which is consistent with previous studies.30)

Our study has several limitations. First, it is important to evaluate additional mediators to prevent suicide. Although there may be many protective factors, parental support has a significant effect on the relationship between suicidal thoughts and life stress.

Second, although this study aimed to analyze a national sample of youth, there are limitations as a result of including only teenagers enrolled in school. Future research should include youth who are not attending school because they may be more vulnerable to stress or may avoid stressors related to school.

Third, these findings are limited to middle-school students, and the results cannot be generalized to youth of all ages. Therefore, additional research should expand the age group of the study population.

Fourth, this analysis is a secondary data analysis using a national sample. Some factors, such as parental marital status, that were found to be related to suicidal ideation in previous studies9) were not included.

Using national data that employed a stratified multistage colonies sampling method, we found that parental support has a mediating effect on stress. As both an independent and a mediating factor, the perception of supportive relationships with parents is an important protective factor against suicidal ideation for Korean middle-school students.

We also found that suicidal ideation was related to several multi-dimensional risk factors. In terms of life stress, many subscales, including physical appearance; physical health; psychological health; economic status; career; academics; and relationships with parents, siblings, friends, peers, and teachers, were related to suicidal ideation. In terms of parental support, emotional, academic, and financial support were all related to an absence of suicidal ideation. These findings indicate that suicide prevention programs should use a comprehensive and integrated approach that addresses all aspects of adolescents' life stress and helps parents foster supportive relationships with them.

Although parental support did not explain all of the risk of suicide, parental support and positive perceptions of adolescents' relationships with their parents could reduce adolescents' suicidal thoughts. These findings suggest the importance of parental support in preventing suicidal behavior and may contribute to the creation of effective intervention programs. Fostering parental support could lead to positive outcomes for children and adolescents who are struggling with life stress and suicidal thoughts. Suicide prevention programs should enhance parental support and help parents support their children by reducing the economic burdens of education, teaching interpersonal communication skills within the family, and strengthening family bonds and attachments.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Han B, Compton WM, Gfroerer J, McKeon R. Prevalence and correlates of past 12-month suicide attempt among adults with past-year suicidal ideation in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:295–302. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott LN, Pilkonis PA, Hipwell AE, Keenan K, Stepp SD. Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal ideation as predictors of suicide attempts in adolescent girls: a multi-wave prospective study. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;58:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: a global imperative. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) (2011): National Center for Injury Prevention and Control [Internet] Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [cited 2016 Mar 15]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Statistics Korea. Suicide rates: aged from 15 to 19 years in Korea. Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park B, Kim SY, Shin JY, Sanson-Fisher RW, Shin DW, Cho J, et al. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in anxious or depressed family caregivers of patients with cancer: a nationwide survey in Korea. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang EH, Hyun MK, Choi SM, Kim JM, Kim GM, Woo JM. Twelve-month prevalence and predictors of self-reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among Korean adolescents in a web-based nationwide survey. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:47–53. doi: 10.1177/0004867414540752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mo SH, Kim HJ, Lee SY, Kim JH, KM Y. A study on support measures for children and adolescents' mental health promotion III. Seoul: Korea Institute for Youth Development; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ra HJ, Park GS, Do HJ, Choi JK, Joe HG, Kweon HJ, et al. Factors influencing the impulse of suicide in adolescence. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2006;27:988–997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romeo RD, McEwen BS. Stress and the adolescent brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1094:202–214. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawyer MG, Sarris A, Baghurst PA, Cornish CA, Kalucy RS. The prevalence of emotional and behaviour disorders and patterns of service utilisation in children and adolescents. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1990;24:323–330. doi: 10.3109/00048679009077699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilburn VR, Smith DE. Stress, self-esteem, and suicidal ideation in late adolescents. Adolescence. 2005;40:33–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandin B, Chorot P, Santed MA, Valiente RM, Joiner TE., Jr Negative life events and adolescent suicidal behavior: a critical analysis from the stress process perspective. J Adolesc. 1998;21:415–426. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Wilde EJ, Kienhorst IC, Diekstra RF, Wolters WH. The relationship between adolescent suicidal behavior and life events in childhood and adolescence. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:45–51. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy MA, Parhar KK, Samra J, Gorzalka B. Suicide ideation in different generations of immigrants. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50:353–356. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wills TA. Social support and the family. In: Blechman EA, editor. Emotions and the family: for better or for worse. New York (NY): Routledge; 1990. pp. 75–98. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim DH, Kang IS, Lee S. Social support, self-concept and self-efficacy as correlates of adolescents' physical activity and eating habits. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2007;28:292–301. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang SG, Shin JH, Hwang YN, Lee EJ, Song SW. Relations between worry, attachment styles and perceived parental rearing in primary school children. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2008;29:854–866. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desforges C, Abouchaar A. The impact of parental involvement, parental support and family education on pupil achievement and adjustment: a review of literature. Annesley: DfES Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connor JJ, Rueter MA. Parent-child relationships as systems of support or risk for adolescent suicidality. J Fam Psychol. 2006;20:143–155. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nunnally JC. Psychometric theory. 2nd ed. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norman G. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2010;15:625–632. doi: 10.1007/s10459-010-9222-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao XL, Zhong BL, Xiang YT, Ungvari GS, Lai KY, Chiu HF, et al. Prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in the general population of China: a meta-analysis. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2015;49:296–308. doi: 10.1177/0091217415589306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kandel DB, Raveis VH, Davies M. Suicidal ideation in adolescence: depression, substance use, and other risk factors. J Youth Adolesc. 1991;20:289–309. doi: 10.1007/BF01537613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhlberg JA, Pena JB, Zayas LH. Familism, parent-adolescent conflict, self-esteem, internalizing behaviors and suicide attempts among adolescent Latinas. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2010;41:425–440. doi: 10.1007/s10578-010-0179-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamborn SD, Felbab AJ. Applying ethnic equivalence and cultural values models to African-American teens' perceptions of parents. J Adolesc. 2003;26:605–622. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(03)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lobo Prabhu S, Molinari V, Bowers T, Lomax J. Role of the family in suicide prevention: an attachment and family systems perspective. Bull Menninger Clin. 2010;74:301–327. doi: 10.1521/bumc.2010.74.4.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheftall AH, Mathias CW, Furr RM, Dougherty DM. Adolescent attachment security, family functioning, and suicide attempts. Attach Hum Dev. 2013;15:368–383. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2013.782649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerfoot M, Harrington R, Dyer E. Brief home-based intervention with young suicide attempters and their families. J Adolesc. 1995;18:557–568. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borowsky IW, Ireland M, Resnick MD. Adolescent suicide attempts: risks and protectors. Pediatrics. 2001;107:485–493. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]