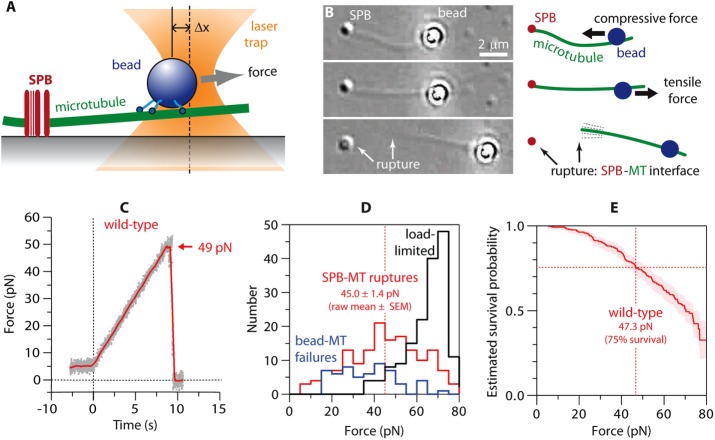

FIGURE 2:

Measuring the strength of individual SPB–microtubule attachments. (A) Beads decorated with kinesins (in the absence of ATP, i.e., in “rigor”) form strong linkages to the microtubules, allowing application of high forces to individual SPB–microtubule attachments using a laser trap. (B) The laser trap (not visible) applies force to a bead linked to an SPB-attached microtubule (MT). Top, initially, the trap pushes the bead toward the SPB, applying compressive force to the SPB-MT interface and causing the MT to buckle. Middle, the direction of force is reversed to apply tensile force to the SPB-MT attachment. Bottom, after the SPB-MT interface ruptures (arrows), the filament remains linked to and pivots around the trapped bead. The SPB appears slightly different in this image due to a slight change in microscope focus. See also Supplemental Movie S2. (C) Tensile force vs. time (force ramp, 5 pN/s) applied to a microtubule attached to a wild-type SPB. Grey dots show raw data. Red trace shows the same data after smoothing (500-ms sliding boxcar average). Dashed vertical line marks the start of the force ramp. Arrow marks rupture at the SPB–microtubule (SPB-MT) interface. (D) Histograms showing outcomes from a series of force ramp experiments using wild-type SPBs. Vertical dashed line marks raw the mean rupture force, computed from only the subset of trials ending with SPB–microtubule rupture. (E) Survival probability as a function of force for microtubule attachments to wild-type SPBs, estimated using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Shaded area shows 95% confidence intervals. Dashed vertical line marks the estimated force at 75% survival.