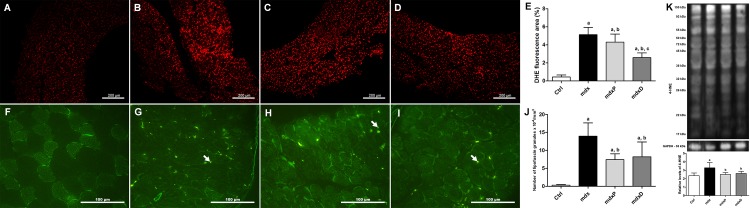

Fig 4. Oxidative stress in dystrophic diaphragm muscle.

Diaphragm (DIA) cross-sections showing dihydroethidium (DHE) fluorescence in C57BL/10 (A), saline-treated mdx mice (B), prednisone-treated mdx mice (C) and diacerhein-treated mdx mice (D). The graphs (E) show the DHE staining area (%) in C57BL/10 mice (Ctrl), saline-treated mdx mice (mdx), prednisone-treated mdx mice (mdxP) and diacerhein-treated mdx mice (mdxD). DIA cross-sections showing autofluorescent lipofuscin granules (white arrow) in Ctrl (F), mdx (G), mdxP (H) and mdxD (I). The graphs (J) show the number of lipofuscin granules x 10−4/mm3 in Ctrl, mdx, mdxP and mdxD groups. In (K), western blotting analysis of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE)-protein adducts. Bands corresponding to protein (top row), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; used as loading control) (bottom row), are shown. The graphs show protein levels in the crude extracts of DIA muscle from Ctrl, mdx, mdxP and mdxD groups. The intensities of each band were quantified and normalized to those of the corresponding Ctrl (in order to obtain relative values). All values expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). aP ≤ 0.05 compared with Ctrl mice, bP ≤ 0.05 compared with mdx mice, cP ≤ 0.05 compared with prednisone-treated mdx mice (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test).