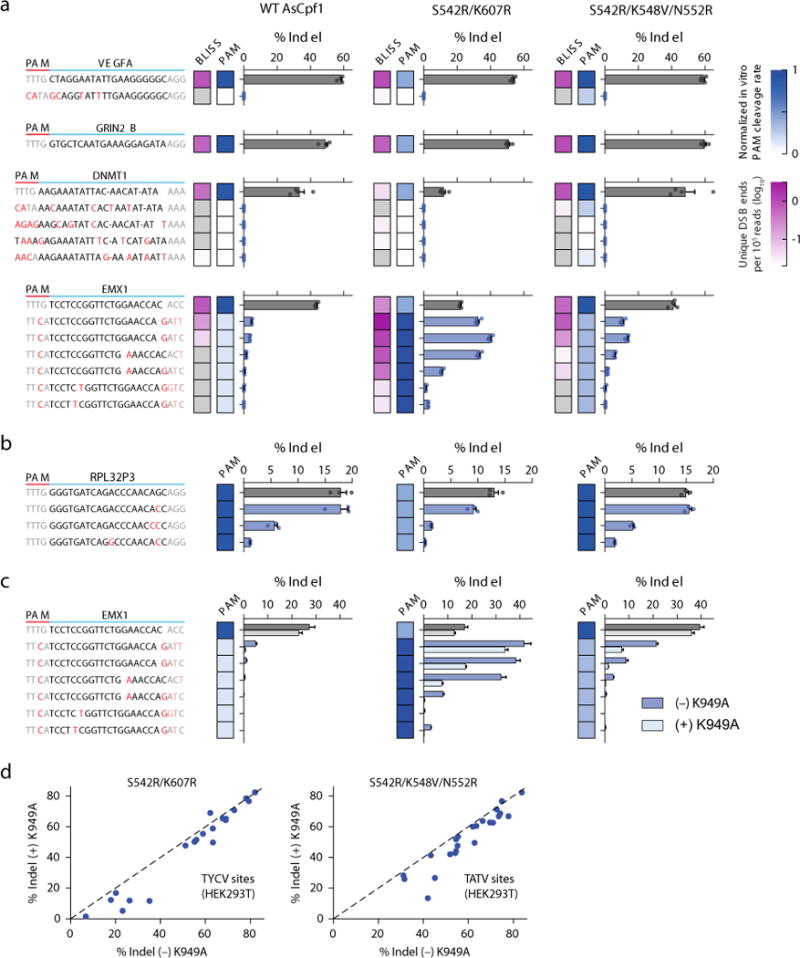

Figure 3.

Specificity of AsCpf1 PAM variants. (a) DNA double-strand breaks labeling in situ and sequencing (BLISS) for 4 target sites (VEGFA, GRIN2B, EMX1, and DNMT1) in HEK293T cells. The log10 number of unique double-strand break (DSB) ends per 105 reads is indicated by the magenta heat map. The normalized PAM cleavage rates from the in vitro cleavage assay in Fig. 2d are indicated by the blue heat map. Each BLISS-identified cleavage site was independently assessed for indel formation (bar graphs). Bars show mean ± s.e.m. for n = 4 transfected cell cultures. Mismatches in bases 21–23 of the target are grayed as they have minimal impact on cleavage efficiency4, 5. (b) Evaluation of an additional target site in the RPL32P3 gene with known TTTV off-target sites5. (c) Addition of a K949A mutation improves the specificity of WT AsCpf1 and variants (see also Supplementary Fig. 8). For (b) and (c), bars show mean ± s.e.m. for n = 3 transfected cell cultures. (d) On-target efficiency of the RR and RVR variants ± K949A. Each dot represents the mean of n = 3 transfected cell cultures.