Abstract

Driven by socioemotional selectivity theory, this study examined whether age moderated the associations of volunteering motives with physical and psychological well-being in a sample of Hong Kong Chinese volunteers. Volunteering motives were measured by the volunteer functions inventory. Findings revealed that even after controlling for demographic characteristics and volunteering experience, age was related to higher social and value motives but lower career motives, and moderated the associations of social and protective motives with well-being. The associations of social motives with physical well-being were positive among older volunteers, but were negative among younger- and middle-aged volunteers. While protective motives were positively related to psychological well-being among all the volunteers, such effects were stronger among younger- and middle-aged volunteers than among older volunteers. Findings highlight the role of age in determining the relationship between volunteering motives and well-being.

Keywords: Volunteering motives, Well-being, Hong Kong Chinese

Introduction

Volunteerism is defined as “any activity intended to help others that are provided without obligation, for which the volunteer does not receive pay or other material compensation” (Harootyan 1996, p. 613). In recent years, there have been an increasing number of older people who actively donated their time and effort as volunteers (Chambre 1993; Independent Sector 2001). With the growth of volunteerism among the aging population, many studies have revealed the physical and psychological benefits of volunteerism over the life course (Li and Ferraro 2005; Lum and Lightfoot 2005; Musick and Wilson 2003; Oman et al. 1999; Onyx and Warburton 2003). Yet, the functional theory of volunteerism (Clary and Snyder 1991; Okun and Schultz 2003) argues that individuals are motivated by different reasons to participate in volunteering work. Examining age differences in volunteering motives, they found that younger volunteers were motivated by a desire to network with others, while older volunteers were motivated by a sense of care and concern for the society (Omoto et al. 2000). In addition, Okun and Schultz (2003) found an inverse relationship between age and career motives (e.g.,, promoting and preparing for future career) and understanding motives (e.g., seeking new experience for personal growth), but a positive relationship between age and social motives (e.g., strengthening existing social relationships). They interpreted these age differences in terms of socioemotional selectivity theory (SST, Carstensen 2006).

The SST proposes that with age, people perceive future time as increasingly limited and thus shift their focus from future-oriented knowledge goals to present-oriented emotionally meaningful goals. Career motives and understanding motives are more future-oriented, while social motives are more present-focused (Okun and Schultz 2003). With aging and the associated future time constraints, people may shift their volunteering motives from career and understanding to social motives. However, Okun and Schultz (2003) did not examine the associations between these age differences in motives and well-being, and thus could not address the question of whether it was adaptive for older adults to hold volunteering motives different from those of younger adults. If the SST is indeed correct that the age differences in goals are resulting from proactive selection, then volunteers may benefit from endorsing volunteering motives that are aligned with their age-relevant goals. To test the hypothesis, this study examined how age would moderate the relationship between volunteering motives and well-being in a sample of Hong Kong Chinese volunteers.

Volunteerism and well-being

Several studies showed that volunteerism was associated with higher self-related physical health (Morrow-Howell et al. 2003; Piliavin and Siegl 2007; Van Willigen 2000) and lower mortality rate (Omanet al. 1999; Musick et al. 1999). Lum and Lightfoot (2005) found a longitudinal effect of volunteerism that people aged over 70 years perceived positive changes in physical health and functioning after participating in volunteering activities. In addition, volunteerism was found to reduce physical pain (Arnstein et al. 2002), increase muscular strength (Fried et al. 2004), and prevent fall-related hip fracture (Warburton and Peel 2008) for older volunteers.

Piliavin and Siegl (2007) examined the psychological benefits of volunteering through analyzing four waves of longitudinal data. Findings from their study revealed that sustained volunteering and participation in different organizations improved volunteers’ psychological well-being over time. Volunteerism, including its diversity, intensity, and duration, also helped in preventing depression among people across age groups (Musick and Wilson 2003; Li and Ferraro 2005). Morrow-Howell et al. (2003) found that older volunteers subjectively evaluated themselves as the ones “feeling better off.” Van Willigen (2000) demonstrated that active volunteering was associated with increased life satisfaction, and such an effect was stronger among older than among younger participants. Other studies have shown that participating in volunteer work was related to positive affect and better psychological well-being among older adults (Greenfield and Marks 2004).

Age, volunteering motives, and well-being

As reviewed above, there is robust evidence for the positive linkage of volunteerism to both physical and psychological well-being. Other studies have revealed that the benefits of volunteerism could be influenced by social integration (Piliavin and Siegl 2007), the intensity of volunteerism (Jirovec and Hyduk 1998; Van Willigen 2000), and structural incentives and barriers of volunteering programs (Warburton et al. 2007). Few studies have investigated the benefits of volunteerism from a motivational perspective.

A recent theory, functional theory of volunteerism (Clary and Snyder 1991; Okun and Schultz 2003), proposes that individuals have different motives to participate in volunteering work. According to the theory, volunteering motives can be categorized into six different dimensions in terms of the meaning or purpose of volunteerism for the individual. Career motives refer to volunteers’ motives of promoting and preparing for future career or maintaining skills that are relevant to the current job. Understanding motives include motives to seek new knowledge, skills, and experiences for personal growth. Social motives are motives to strengthen the existing relationships with others. Enhancement motives include motives to maintain or enhance self-esteem, self-worth, or positive affect. Value motives refer to volunteers’ desires to express altruistic and humanitarian values through providing voluntary work to others. Protective motives protect people from the negative characteristics of themselves and assure them that they are good and competent individuals. Finally, Okun and Schultz (2003) separated an item on making friends from the subscale on enhancement motives and treated it as the seventh volunteering motive. The motive of making friends refers to volunteers’ desire of making friends and expanding their social networks.

Previous studies have examined age differences in these volunteer motives. Okun and Schultz (2003) found an inverse association of age with career and understanding motives, but a positive relationship between age and social motives. The observed relationships between age and volunteering motives remained unchanged even when other researchers statistically controlled for the effect of volunteering experience (Dávila and Díaz-Morales 2009). Omoto et al. (2000) revealed that younger volunteers were motivated to develop social relationships with novel others, and older volunteers were motivated to show care and concern to the society. Clary et al. (1996) showed that younger volunteers endorsed higher career, understanding, and protective motives than did older volunteers.

These findings could be explained by the SST (Carstensen 2006). The SST contends that individual’s perception of future time influences how she/he would prioritize different goals over the life span. In particular, when the individual perceives future time as open-ended, she/he tends to focus more on future-oriented goals such as knowledge seeking and self-expansion. However, with age, the individual perceives future time as increasingly more limited. She/he then invests more to pursue emotionally meaningful goals. Such goals can be achieved by maintaining a closer social network (Fung et al. 2001) and maximizing emotional gratification (Carstensen et al. 2003) in the realms of emotions and social relationships. Applying the SST (Carstensen 2006) to volunteering motives, Okun and Schultz (2003) postulate that the motives of making friends, and the career and understanding motives are more age-relevant for younger people to gain new knowledge and expand the social network. The remaining volunteering motives (social, enhancement, protective, and value motives) are more related to emotionally meaningful goals and thus should be more age-relevant for older people.

Although these studies have revealed age differences in volunteering motives, a major question remains: Are these age differences in volunteering motives adaptive? In other words, does age moderate the relationships between volunteering motives and physical and psychological well-being among volunteers of different ages To the best of our knowledge, only Pushkar et al. (2002) have assessed volunteering motives with a single factor and found that older volunteers showed lower happiness when having higher volunteering motives. Considering that their findings were based on older volunteers only, these findings could not address the issue of whether the associations between volunteering motives and well-being differed by age.

The present study

To fill in the gap, the present study examined the associations of age-related volunteering motives, and physical and psychological well-being, in a sample of Hong Kong Chinese volunteers. As found by Okun and Schultz (2003) among a sample of Americans, age was negatively related to career and understanding, which presumably reflected future-oriented goals. Age was positively related to social motives, which could be categorized as emotionally meaningful goals. We first aimed to replicate these age differences in volunteering motives among Hong Kong Chinese volunteers. We expected that career and understanding motives would be negatively associated with age, but social motives would be positively associated with age.

More importantly, based on the SST (Carstensen 2006), we predicted that volunteers would obtain the greatest physical and psychological benefits when their volunteering motives were aligned with their age-relevant social goals. In particular, older volunteers would enjoy better physical and psychological well-being when they endorsed emotionally meaningful volunteering motives, such as social motives, to a greater extent; younger volunteers would enjoy better physical and psychological well-being when they endorsed future-oriented volunteering motives, such as career and understanding motives, to a greater extent.

Method

Participants

The sample included 174 participants aged from 25 to 91 years (60.9 % female; M age = 48.25, SD = 20.75). We recruited participants by convenience sampling through posting recruitment advertisements in community centers in Hong Kong, China. The potential participants were included in the study when they met the following criteria: (1) were aged 18 years or older; (2) were currently engaging in volunteering service; (3) were able to read and write Chinese. Of all the participants, 50.3 % were married; 64.4 % were employed; 58.6 % had no religion, and the remaining participants were religious. Thirty percent of participants had received primary or lower education, 21.3 % had secondary education, and 47.1 % had tertiary education. Participants’ monthly income ranged from less than HK $5,000 to HK$ 30,000 or above, with 52.2 % having more than HK $10,000 every month. All the participants reported volunteering experience: 30.5 % volunteered for a year or less, 31.6 % volunteered for 2–5 years, 19.5 % volunteered for 5–10 years, and 18.4 % volunteered for over 10 years; and 44 % volunteered more than once every month regularly.

Measures

Volunteering motives

Volunteering motives were assessed by the volunteer functions inventory (VFI) (Clary et al. 1998). It consists of 30 items, tapping 6 volunteering motives with 5 items for each motive: value (e.g., “I feel compassion toward people in need”), understanding (e.g., “Volunteering lets me learn things through direct, hands-on experience”), career (e.g., “I can make new contacts that might help my business or career”), protection (e.g., “Volunteering is a good escape from my own troubles”), enhancement (e.g., “volunteering makes me feel important”) and social motives (e.g., “People I am close to want me to volunteer”). Participants were asked to rate each item on a seven-point Likert scale. The ratings on each subscale were averaged, with a higher mean score representing a higher endorsement of the particular volunteering motive. In addition, following Okun and Schultz (2003)’s conceptualization, we took the item “volunteering is a way to make new friends” from the enhancement motives subscale as the measure of the motive to make friends, and computed the average of the remaining four items as the mean score of enhancement motives. Based on inter-item reliability analysis, we deleted an item from the value subscale and an item from the understanding subscale. After that, the alpha coefficients of all the subscales were acceptable, ranging from .73 to .87.

Physical well-being

Adopting the measure from Thoits and Hewitt (2001), we assessed perceived physical well-being by three items: “How satisfied you are with your health in general?,” “How would you rate your health at the present time?” and “To which extent your daily activities are limited in any way by your health or health-related problems?” (reverse coded). Participants were asked to rate each item on a five-point Likert scale and the ratings were averaged across items. A higher mean score indicates that participants perceived better physical health. The alpha coefficient of the three items was .75.

Psychological well-being

Psychological well-being was measured in terms of life satisfaction, with the Chinese version of Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985, translated by Sachs 2003). It consists of five items, and participants were asked to respond to each item on a seven-point Likert scale. Participants’ ratings were averaged, and a higher mean score indicates a higher level of life satisfaction. The scale demonstrated a satisfactory internal consistency, with an alpha coefficient of .83.

Potential covariates

To rule out the possibility that the findings of the study were confounded by demographic characteristics and volunteering experience, potential covariates (sex, religion, marital status, socioeconomic status, the duration, and regularity of volunteering experience) were also included. Sex was coded as male or female; religion was reported as having a religion or not; and marital status was coded as unmarried or married. Socioeconomic status (SES) was assessed in terms of education level and monthly income. Education level was coded as “1 = primary school or below,” “2 = secondary school,” and “3 = tertiary education or above”; and monthly income was coded from “1 = less than HK$5000” to “7 = HK $30000 or above.” The composition score of SES was calculated by adding up the standardized education level and monthly income. The duration of volunteering experience was assessed by the time participants had been a volunteer on a four-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = less than one year” to “4 = more than 10 years.” The regularity of volunteering experience was assessed by the number of times participants had participated in volunteering activities every month. Among all the scales listed above, the measures of volunteering motives and physical well-being were not available in Chinese. Two bilingual researchers translated the measures from English into Chinese through the translation and back-translation procedure.

Results

Table 1 showed the correlations between main variables and covariates. Sex, marital status, SES, the duration, and regularity of volunteering experience were related to age, volunteering motives, and well-being. We thus included them as covariates in all the regression analyses reported below.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and simple correlations between main variables and covariates

| Mean (SD)/percentage | Age | Enhancement motives | Career motives | Social motives | Value motives |

Understanding motives | Protective motives | Making friends | Physical well-being | Life satisfaction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhancement motives | 4.76 (1.15) | .456** | |||||||||||||

| Career motives | 3.52 (1.41) | −.399** | .132 | ||||||||||||

| Social motives | 3.96 (1.37) | .613** | .671** | .021 | |||||||||||

| Value motives | 5.49 (.88) | .320** | .621** | .024 | .502** | ||||||||||

| Understanding motives | 5.33 (.90) | .291** | .643** | .171* | .451** | .597** | |||||||||

| Protective motives | 4.33 (1.33) | .556** | .746** | .050 | .728** | .556** | .593** | ||||||||

| Making friends | 5.45 (1.22) | .281** | .521** | .185* | .472** | .565** | .613** | .502** | |||||||

| Physical well-being | 3.67 (.78) | .198** | .241** | −.058 | .144 | .266** | .232** | .251** | .048 | ||||||

| Life satisfaction | 4.83 (1.10) | .350** | .296** | −.186* | .270** | .202** | .212** | .332** | .139 | .471** | |||||

| Sex (% female) | 60.9 % | .257** | .058 | −.173* | .088 | .074 | −.002 | .153* | .008 | .071 | .227** | ||||

| Religion (% religious) | 41.4 % | .024 | −.024 | −.045 | .031 | .040 | .127 | .017 | −.064 | .050 | .125 | ||||

| Marital status (% married) | 50.3 % | .573** | .208* | −.265** | .229** | .120 | .020 | .248** | .007 | .227** | .419** | ||||

| SES | .13 (1.80) | −.757** | −.451** | .293** | −.596** | −.272** | −.258** | −.592** | −.297** | −.053 | −.103 | ||||

| Volunteering duration | – | .299** | .237** | −.080 | .173* | .188* | .292** | .172* | .107 | .189* | .191* | ||||

| Volunteering regularity | – | .343** | .246** | −.137 | .240** | .208** | .144 | .184* | .218** | .245** | .209** | ||||

* p < .05; ** p ≤ .01; *** p ≤ .001

Age and volunteering motives

To investigate the net relationship between age and volunteering motives, we performed a set of hierarchical regression analyses on each of volunteering motives by entering the above covariates into Block 1 and age into Block 2. Results revealed that after statistically controlling for the covariates, age was positively associated with social motives (B = .033, SE = .008, β = .501, t = 3.940, p < .001) and value motives (B = .015, SE = .007, β = .368, t = 2.358, p = .020). In contrast, age was negatively related to career motives (B = −.035, SE = .010, β = −.516, t = −3.475, p = .001).

Age, volunteering motives, and well-being

To examine how age and volunteering motives interacted in determining well-being, hierarchical regression analyses were separately conducted on physical and psychological well-being (Table 2). The covariates were controlled in Block 1; age and volunteering motives were entered into Block 2; and age by volunteering motives interactions were entered in Block 3. The interaction terms were calculated after mean centering each variable. We also normalized the skewed distributions of physical and psychological well-being by taking square roots.

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression analyses of physical well-being, life satisfaction, and depression

| Physical well-being | Life satisfaction | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | ΔR 2 | B | SE | β | ΔR 2 | |

| Block 1 | .093* | .234*** | ||||||

| Sex | .013 | .035 | .030 | .069 | .039 | .130 | ||

| SES | .011 | .010 | .092 | .013 | .011 | .088 | ||

| Marital status | .070 | .035 | .163* | .203 | .039 | .389* | ||

| Volunteering duration | .021 | .016 | .105 | .021 | .016 | .105 | ||

| Volunteering regularity | .009 | .004 | .199* | .007 | .004 | .115 | ||

| Block 2 | .129** | .154*** | ||||||

| Age | .001 | .002 | .122 | .002 | .002 | .139 | ||

| Enhancement motives | −.021 | .025 | −.115 | −.003 | .027 | −.015 | ||

| Career motives | .000 | .014 | −.002 | −.034 | .015 | −.185* | ||

| Social motives | −.013 | .019 | −.083 | .029 | .021 | .152 | ||

| Value motives | .039 | .026 | .159 | −.023 | .028 | −.076 | ||

| Understanding motives | .039 | .028 | .164 | .011 | .030 | .037 | ||

| Protective motives | .065 | .023 | .396** | .085 | .025 | .424** | ||

| Making friends | −.043 | .018 | −.247* | −.008 | .019 | −.038 | ||

| Block 3 | .079* | .051+ | ||||||

| Age × enhancement | −.000 | .001 | −.097 | .002 | .001 | .142 | ||

| Age × career | .001 | .001 | .115 | .000 | .001 | −.045 | ||

| Age × social | .002 | .001 | .283* | .002 | .001 | .172 | ||

| Age × value | .000 | .001 | −.010 | .000 | .002 | −.063 | ||

| Age × understanding | −.002 | .001 | −.173 | .0001 | .001 | .004 | ||

| Age × protective | .000 | .001 | −.050 | −.004 | .001 | −.369** | ||

| Age × making friends | −.001 | .001 | −.155 | .000 | .001 | .027 | ||

B unstandardized coefficient, SE standardized error, β standardized coefficient

+ p < .10; * p < .05; ** p ≤ .01; *** p ≤ .001

Results from Block 2 showed a significant main effect of volunteering motives on physical and psychological well-being. Physical well-being was positively related to protective motives (B = .065, SE = .023, β = .396, t = 2.818, p = .005) and negatively related to the motive of making friends (B = −.043, SE = .018, β = −.247, t = 2.417, p = .017). Psychological well-being was negatively related to career motives (B = −.034, SE = .015, β = −.185, t = −2.227, p = .027) and was positively related to protective motives (B = .085, SE = .025, β = .424, t = 3.402, p = .001).

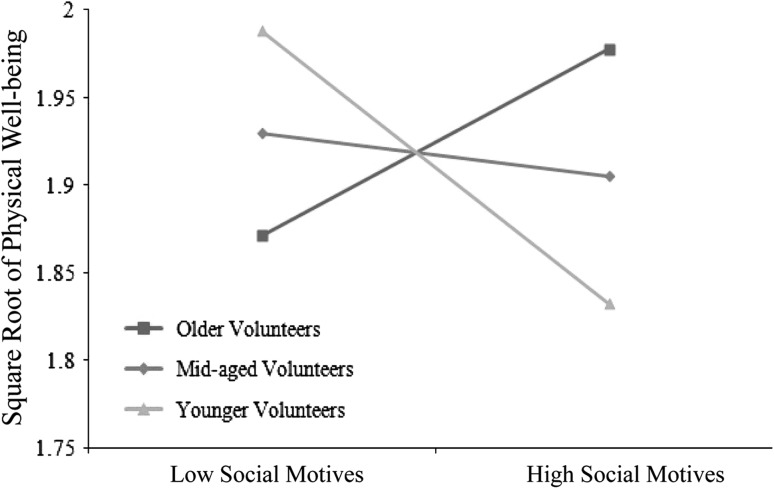

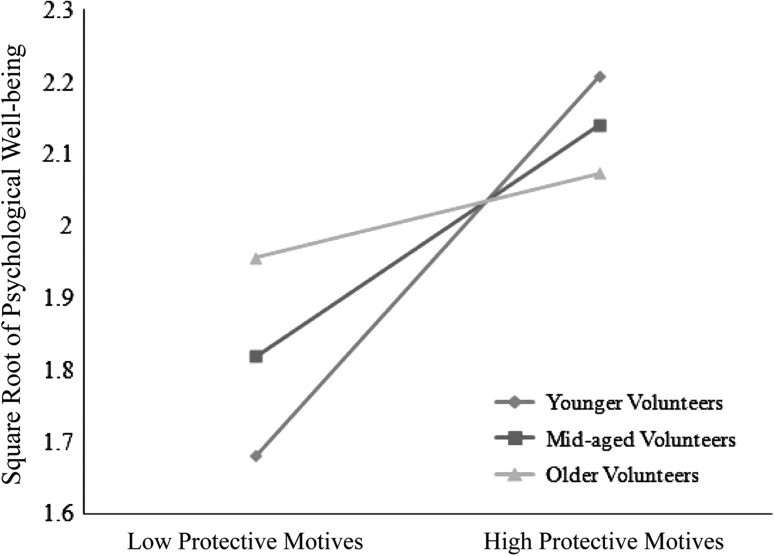

Results from Block 3 showed a significant interaction effect of age by volunteering motives on physical and psychological well-being. Specifically, age and social motives showed a significant interaction effect on physical well-being, B = .002, SE = .001, β = .283, t = 2.571, p = .011. Further simple slope analysis illustrated that the associations between social motives and physical well-being were positive among older volunteers (69.00–91.00 years, 1 standard deviation above mean age), but were negative among middle-aged (27.50–69.00 years, within 1 standard deviation of mean age) and younger (25.00–27.50 years, 1 standard deviation below mean age) volunteers, see Fig. 1. Age and protective motives also had an interaction effect on psychological well-being, B = −.004, SE = .001, β = −.369, t = −3.030, p = .003. The simple slope analysis showed that protective motives had the strongest positive relationship with psychological well-being among younger volunteers (25.00–27.50 years, 1 standard deviation below mean age), followed by middle-aged volunteers (27.50–69.00 years, within 1 standard deviation of mean age group), and then older volunteers (69.00–91.00 years, 1 standard deviation above mean age), see Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Interaction effect of age and social motives on physical well-being

Fig. 2.

Interaction effect of age and protective motives on psychological well-being

Discussion

This study examined the moderating role of age in the associations between volunteering motives, and physical and psychological well-being, in a sample of Hong Kong Chinese volunteers. We found that even after statistically controlling for demographic characteristics and volunteering experience, age was positively related to social and value motives, but was negatively associated with career motives. Age also moderated the associations of social and protective motives with well-being. The associations of social motives with physical well-being were positive among older adults, but were negative among middle- and younger-aged adults. While protective motives were positively related to psychological well-being among all the volunteers, such associations were stronger among younger- and middle-aged volunteers than among older volunteers.

Our findings that age correlated positively with social motives, but negatively with career motives were consistent with the prior findings of Okun and Schultz (2003), and could be explained in terms of the SST (Carstensen 2006). According to the theory, people tend to prioritize emotionally meaningful goals over future-oriented goals as they grow older. The positive association between age and social motives, and the negative association between age and career motives, may suggest that while older people pay more efforts to sustain and strengthen their existing social relationships through volunteering, younger people focus more on self-expansion and career development in the volunteering context.

In addition, we found that age was positively related to value motives. This is consistent with the existing literature that older adults participated in voluntary work to strive for life purpose and meaning in the society (Omoto et al. 2000). Older adults’ endorsement of higher value motives may reflect their greater desire to show their care and concern to other people. The fact that the relationship between age and value motives was found in our Hong Kong Chinese sample, but not in Okun and Schultz (2003)’s American sample, highlighted the importance of conducting cross-cultural studies to determine whether some age differences in volunteering motives might be culturally specific.

Although we did not find an inverse relationship between age and understanding motives, we found that volunteers of all ages had high understanding motives, see Table 1. This is probably because learning per se is important throughout adulthood. Age groups might just differ in the knowledge and skills that they consider age-relevant (Barlow and Hainsworth 2001). While learning new knowledge and skills are future-oriented for younger adults, learning social skills through volunteering may fulfill the emotionally meaningful goals for older adults. Future studies should directly examine whether both younger and older volunteers are motivated to learn new materials when they find the materials useful for their age period.

We also found that the motive of making friends was negatively related to physical well-being and that career motive was negatively related to psychological well-being. This may be the case because the motive of making new friends makes volunteers spend too much energy on developing new social relationships, through volunteering for more hours, serving more organizations, and attending different volunteer-training programs, which may be unavoidably taxing for physical health. The negative association between career motives and psychological well-being might be explained by the salient self-oriented tendency among volunteers with career motives. These volunteers treat volunteering as job trainings, caring more about their own career advancement than serving their service recipients. Given that people who volunteer for self-oriented reasons are more likely to perceive volunteering as stressful relative to those who volunteer for other-oriented reasons (Konrath et al. 2012), volunteers with career motives may receive less psychological benefits through volunteering activities.

Moreover, the findings from the study showed that protective motives were positively related to physical and psychological well-being; the association between protective motives and psychological well-being was less pronounced among older volunteers than among middle- and younger-aged volunteers. The positive association of protective motives with physical and psychological well-being might be explained by the folk belief that volunteering is a pathway to good luck and blessings, leading to better lives and even after-lives (Cheung et al. 2006). However, such an association was stronger among younger adults than among older adults. This might be the case because older adults tend to use more internal strategies (e.g., positive reappraisal, attention deployment), but fewer external strategies (e.g., suppression), to regulate their emotions (Carstensen et al. 2000; Gross et al. 1997). This tendency might make older adults less likely to use external strategies such as volunteering to escape from their trouble and achieve better psychological well-being, relative to their middle-aged and younger counterparts.

More relevant to our hypothesis, we found an age-specific effect of social motives on well-being. Whereas social motives were positively related to physical well-being among older volunteers; such relationships were negative among middle-aged and younger volunteers. These findings confirmed our hypothesis that volunteering motives might differentially benefit physical well-being, depending on their relevance to age-specific goals. Consistent with the SST (Carstensen 2006), sustaining and strengthening existing social relationships through volunteering may be more important for older than younger people. As a result, endorsing such motives to a greater extent may benefit the physical well-being of older adults more than that of their younger counterparts. Future studies should explore the mechanisms of this benefit. The benefit might occur through encouraging older adults to actively engage in more social activities, which may be physical; or indirectly through maintaining existing social networks, which is the most important source of life meaning among older adults (Fung et al. 2001).

It should be noted that, even though age was positively related to value motives, we failed to reveal a significant beneficial effect of value motives on physical or psychological well-being among volunteers of different age. Prior studies demonstrated that the fulfillment of altruistic volunteering motives benefited the psychological well-being for volunteers (Finkelstein 2007, 2008). A report from Agency for Volunteer Service (2010) further suggested that volunteers obtained benefits when they knew their clients were satisfied with their service. In this study, volunteers might be unable to benefit from volunteering motives because they were unclear about whether their services were really helpful to the clients, thereby accomplishing their altruistic goals. Future studies should consider whether fulfillment of volunteering motives moderated the interaction between age and volunteering motives on well-being.

Moreover, age-specific effects of enhancement motives on well-being were not found. This null effect might be culturally specific. Okun and Schultz (2003) suggested older people’s volunteering was driven by positive emotion and self-worth; this might not be the case for older Hong Kong Chinese. In fact, prior studies found that older Hong Kong Chinese looked away from positive faces (Fung et al. 2008), and those with high interdependence even attended to and remembered more negative stimuli (Fung et al. 2010). Remembering the unhappiest rather than the happiest day predicted low life satisfaction among East Asians; but the result was the opposite among the Americans (Oishi 2002). Therefore, enhancement motives, with their aim of promoting favorable self-view, self-esteem, and positive emotions, might not affect Chinese volunteers as much as it did American volunteers in previous studies (Okun and Schultz 2003), resulting in no age differences in enhancement motives, or age by enhancement motives interactions on well-being. Future studies should consider whether culture might moderate the associations between age-related motives and well-being.

The existing literature on volunteerism has revealed that the physical and psychological benefits of volunteerism are moderated by numerous moderators like social integration and personality (Jirovec and Hyduk 1998; Piliavin and Siegl 2007; Warburton et al. 2007; Pushkar et al. 2002; Van Willigen 2000). Adding to these findings, this study revealed a significant moderating role of age in the relationship between volunteering motives and well-being. However, we acknowledged several limitations of this study. First, the study is correlational in nature. Experimental studies and longitudinal studies are needed to further test whether volunteering improves the physical and psychological well-being among volunteers of different age through satisfying their goals. In particular, studies on sustained volunteerism revealed that the endorsement of volunteering motives only predicted volunteering experience at the beginning but not for longer periods (Chacon et al. 2007; Finkelstein 2006; Finkelstein et al. 2005). Future studies should further examine the well-being benefits of volunteering motives in longitudinal studies to disentangle the short-term and long-term effects of volunteering motives among different age groups. Moreover, our results are based on a relatively small sample of Hong Kong Chinese volunteers. Future studies are needed to replicate our findings with a larger and more diverse sample.

Despite these limitations, we provided the first evidence that social and protective motives in volunteering were differentially related to well-being among different age groups. These findings should be of use to professionals and volunteering agencies who designed volunteering programs for different age groups. In addition, these findings lay the foundation for future studies on the mechanisms through which volunteering might benefit older adults.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Hong Kong Research Grants Council Earmarked Research Grant CUHK444210. The authors thank Nga Ming Fung for the help in the collection of the data for this study.

Contributor Information

Yuen Wan Ho, Email: spookyho@gmail.com.

Helene H. Fung, Email: hhlfung@psy.cuhk.edu.hk

References

- Arnstein P, Vidal M, Well-Federman C, Morgan B, Caudill M. From chronic pain patients to peer: benefits and risks of volunteering. Pain Manag Nurses. 2002;3(3):94–103. doi: 10.1053/jpmn.2002.126069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow J, Hainsworth J. Volunteerism among older people with arthritis. Ageing Soc. 2001;21:203–217. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X01008145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science. 2006;312:1913–1915. doi: 10.1126/science.1127488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Mayr U, Nesselroade JR. Emotional experience in everyday life across adult life-span. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79:644–655. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Fung H, Charles S. Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motiv Emot. 2003;27:103–123. doi: 10.1023/A:1024569803230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chacon F, Vecina ML, Davila MC. The three-stage model of volunteers’ duration of service. Social Behav Personal. 2007;35:627–642. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2007.35.5.627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chambre SM. Volunteerism by elder: past trends and future prospects. The Gerontologist. 1993;33:221–228. doi: 10.1093/geront/33.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung FYL, Tang CS, Yan ECW. A study of older Chinese in Hong Kong. J Soc Serv Res. 2006;32:193–209. doi: 10.1300/J079v32n04_11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clary EG, Snyder M. A functional analysis of altruism and prosocial behavior: the case of volunteerism. In: Clark M, editor. Review of personality and social psychology. Newbury Park: Sage; 1991. pp. 119–148. [Google Scholar]

- Clary EG, Syder M, Stukas AA. Volunteers’ motivations: findings from a national survey. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q. 1996;25:485–505. doi: 10.1177/0899764096254006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clary EG, Ridge RD, Stukas AA, Snyder M, Copeland J, Haugen J, Miene P. Understanding and assessing in motivations of volunteers: a functional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74:1516–1530. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dávila MC, Díaz-Morales JF. Age and motives for volunteering: further evidence. Eur J Psychol. 2009;5(2):82–95. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein MA. Dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior: motives, motive fulfillment, and role identity. Soc Behav Personal. 2006;34:603–616. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2006.34.6.603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein MA. Correlates of satisfaction in older volunteers: a motivational perspective. Int J Volunt Adm. 2007;24:6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein MA. Volunteer satisfaction and volunteer action: a functional approach. Soc Behav Personal. 2008;36:9–18. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2008.36.1.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein MA, Penner LA, Brannick MT. Motive, role identity, and prosocial personality as predictors of volunteer activity. Soc Behav Personal. 2005;33:403–418. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2005.33.4.403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Carlson MC, Freedman M, Frick KD, Glass TA, Hill J, McGill S, Rebok GW, Seeman T, Tielsch J, Wakik BA, Zeger S. A social model for health promotion for an aging population: initial evidence on the experience corps model. J Urban Health. 2004;81(1):64–78. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung HH, Carstensen LL, Lang F. Age-related patterns in social networks among European-Americans and African-Americans: implications for socioemotional selectivity across the life span. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2001;52:185–206. doi: 10.2190/1ABL-9BE5-M0X2-LR9V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung HH, Isaacowitz DM, Lu A, Wadliinger HA, Goren D, Wilson HR. Age-related positivity enhancement is not universal: older Hong Kong Chinese look away from positive stimuli. Psychol Aging. 2008;23:440–446. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.2.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung HH, Isaacowitz DM, Lu AY, Li T. Interdependent self-construal moderates the age-related negativity reduction effect in memory and visual attention. Psychol Aging. 2010;25:321–329. doi: 10.1037/a0019079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield EA, Marks NF. Formal volunteering as a protective factor for older adults’ psychological well-being. J Gerontol. 2004;5:258–264. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.5.s258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Carstensen LC, Pasupathi M, Tsai J, Gottestam K, Hsu AYC. Emotion and aging: experience, expression, and control. Psychol Aging. 1997;12:590–599. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.12.4.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harootyan RA. Volunteer activity by older adults. In: Birren JE, editor. Encyclopedia of gerontology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 613–620. [Google Scholar]

- Independent Sector (2001) Giving and volunteering in the united states: findings from a national survey (online version). http://www.independentsector.org/programs/research/GV01main.html. Accessed 3 Sep 2010

- Jirovec RL, Hyduk CA. Type of volunteer experience and health among older adult volunteers. J Gerontol Soc Work. 1998;30:29–42. doi: 10.1300/J083v30n03_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Konrath S, Fuhrel-Forbis A, Lou A, Brown S. Motives for volunteering are associated with mortality risk in older adults. Health Psychol. 2012;31:87–96. doi: 10.1037/a0025226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YQ, Ferraro KF. Volunteering and depression in later life: Social benefit or selection processes? J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46:68–84. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum TY, Lightfoot E. The effects of volunteering on the physical and mental health of older people. Res Ageing. 2005;27:31–35. doi: 10.1177/0164027504271349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow-Howell N, Hinterlong J, Rozario PA, Tang FY. Effects of volunteering on the well-being of older adults. J Gerontol. 2003;58B:137–145. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.3.s137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick MA, Wilson J. Volunteering and depression: the role of psychological and social resources in different age groups. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:259–269. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick M, Herzog AR, House JS. Volunteering and mortality among older adults: findings from a national sample. J Gerontol. 1999;54B:S173–S180. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.3.s173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi S. The experiencing and remembering of well-being: a cross-cultural analysis. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2002;28:1398–1406. doi: 10.1177/014616702236871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okun MA, Schultz A. Age and motives for volunteering: testing hypotheses derived from soceioemotional selectivity theory. Psychol Aging. 2003;18:231–239. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oman D, Thoresen CE, McMahon K. Volunteerism and mortality among the community dwelling elderly. J Health Psychol. 1999;4:301–316. doi: 10.1177/135910539900400301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoto AM, Snyder M, Martino SC. Volunteerism and the life course: investigating age-related agendas for action. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;22:181–197. [Google Scholar]

- Onyx J, Warburton J. Volunteering and health among older people: a review. Aust J Ageing. 2003;22:65–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2003.tb00468.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piliavin JA, Siegl E. Health benefits of volunteering in the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48:450–464. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pushkar D, Reis M, Morros M. Motivation, personality and well being in older volunteers. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2002;55:141–162. doi: 10.2190/MR79-J7JA-CCX5-U4GQ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs J. Validation of the satisfaction with life scale in a sample of Hong Kong University Students. Psychologia. 2003;46:225–234. doi: 10.2117/psysoc.2003.225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Agency for Volunteer Service (2010) Survey on volunteering in Hong Kong survey of members of the public. http://www.volunteerlink.net/datafiles/A034.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2011

- Thoits PA, Hewitt LN. Volunteer work and well-being. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42:115–131. doi: 10.2307/3090173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Willigen M. Differential benefits of volunteering across the life course. J Gerontol. 2000;55B:308–318. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.5.s308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton J, Peel NM. Volunteering as a productive ageing activity: the association with fall-related hip fracture in later life. Eur J Ageing. 2008;5:129–136. doi: 10.1007/s10433-008-0081-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton J, Paynter J, Petriwskyj A. Volunteering as a productive aging activity: incentives and barriers to volunteering by Australian seniors. J Appl Gerontol. 2007;26:333–354. doi: 10.1177/0733464807304568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]