Abstract

Intraocular lymphoma (IOL) is a rare lymphocytic malignancy which contains two main distinct forms. Primary intraocular lymphoma (PIOL) is mainly a sub-type of primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL). Alternatively, IOL can originate from outside the central nervous system (CNS) by metastasizing to the eye. These tumors are known as secondary intraocular lymphoma (SIOL). The IOL can arise in the retina, uvea, vitreous, Bruch's membrane and optic nerve. There are predominantly of B-cell origin; however there are also rare T-cell variants. Diagnosis remains challenging for ophthalmologists and pathologists, due to its ability to masquerade as noninfectious or infectious uveitis, white dot syndromes, or occasionally as other metastatic cancers. Laboratory tests include flow cytometry, immunocytochemistry, interleukin detection (IL-10: IL-6, ratio >1), and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. Methotrexate-based systemic chemotherapy with external beam radiotherapy and intravitreal chemotherapy with methotrexate are useful for controlling the disease, but the prognosis remains poor. Therefore, it is important to make an early diagnose and treatment. This review is focused on the clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of the IOL.

Keywords: intraocular lymphoma, central nervous system, diagnosis, treatment, prognosis

BACKGROUND

The designation of intraocular lymphoma (IOL) includes primary intraocular lymphoma (PIOL), mainly arising from the central nervous system (CNS) and secondary intraocular lymphoma (SIOL, from outside the CNS as metastasis from a non-ocular neoplasm)[1]–[2]. IOL incidence is very low. Most cases are of B-cell origin and associated with primary CNS non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Fewer cases are of T-cell origin. Intraocular T-cell lymphomas are uncommon, some are secondary to metastatic systemic T-cell lymphomas including primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PCPTCL), the NK-T cell lymphoma, and rarely adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL)[3]–[7], and the disease is usually confined to the iris and ciliary body and peripheral choroid. The most common PIOL by far is primary vitreoretinal lymphoma (PVRL). SIOL has different clinical features and prognosis[8], and the most common subtype is systemic diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL)[9]. Although still rare, the incidence of IOL has increased in the recent years, and prognosis remains poor. Here, we summarize mainly the current literature on IOL.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of IOL has been increasing in recent years, due to the increase in the patients of immunodeficiency and immunosuppression, the increase in life expectancy, and the improvements in diagnostic tools[8],[10]. The overall incidence of IOL has been estimated to represent 1.86% of ocular malignant tumors[11]. The median age of this disease is 50-60y[12]–[13], with a range between 15-85 years of age[14]. These are estimated to represent 4%-6% of primary brain tumors and 1%-2% of extranodal lymphomas[15]–[16]. Among IOL patients, the percentage of cases that involve the CNS is 60%-80%[17]. While 15%-25% of primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) patients develop ophthalmic manifestations of lymphoma, 56%-90% of PIOL patients have or will develop CNS manifestations of lymphoma[18]. In terms of gender, some reported that women were more commonly affected than men by 2:1[19]–[21]. But some reported that even greater cases occurred in men[22]. There appears to be no racial predilection for the disease[22]–[23].

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of IOL remains unclear. Multiple hypotheses of lymphomagenesis are involved. Immunocompromise, Epstein-Barr virus, and Toxoplasma gondii infection may be the related factors[24]–[26]. Moreover, an infectious antigen driven B-cell expansion may be the primary trigger, which then becomes cloned[8]. Thus, genetic, immunologic, and microenvironmental factors are probably necessary in order to induce malignant B-cell phenotype[27]. Proofs of causation are still lacking, and the lymphomagenesis requires further investigation.

CLINICAL FEATURES

PIOL is a masquerade syndrome that mimics uveitis, even responds to steroid therapy, which makes the diagnosis difficult. Ocular disease is bilateral in 64%-83% of cases[28]. Blurred vision, reduced vision, and floaters are the common initial subjective symptoms[17]. More than 50% of patients have significant vitreous haze and cells that can be seen insheets or clumps with vision impairment[29]. Posterior vitreous detachment and hemorrhage may occur occasionally[30]. Posterior uveitis is the most common presenting symptoms, and anterior segment inflammatory findings are frequently absent[18]. Another characteristic from optical coherence tomography (OCT) is the development of creamy lesions with orange-yellow infiltrates to the retina or retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)[1],[31]–[32]. They can give rise to a characteristic “leopard skin” pigmentation overlying the mass which may be seen in fluorescein angiography (FA)[32]–[35]. There may beisolated subretinal lesionsor associated exudative retinal detachment[23],[33]. A single vitreous lesion is rare, sometimes simple vitreous inflammatory response or optic nerve infiltration may occur[36]. At presentation of PIOL, 56%-90% patients have or will develop CNS manifestations of lymphoma[14]. Sometimes IOL may masquerade as bilateral granulomatous panuveitis[37]. When there is infiltration to the brain, behavioral changes and alteration in cognitive function may occur[38].

Intraocular T-cell lymphomas are uncommon, some of them are secondary to metastatic systemic T-cell lymphomas. SIOL should be considered when there is a bilateral sudden and severe inflammatory reaction of the anterior segment that does not respond to treatment or recurs. Anterior reaction and keratic precipitates may be presented especially in SIOL[39]. The most common ocular manifestation of this disease is non-granulomatous anterior uveitis and vitritis. Other rare ocular symptoms include inflammatory glaucoma, neurotrophic keratopathy, fully dilated pupil, and choroidal detachment[40]. Previous systemic primary site reported indicated that the skin was the most common site. Concurrent CNS involvement was reported in 31.0% cases[41].

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

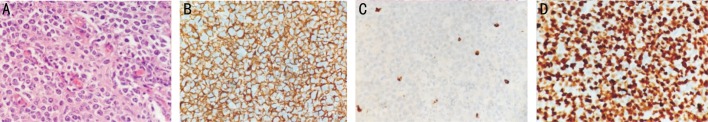

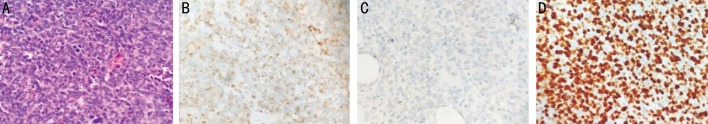

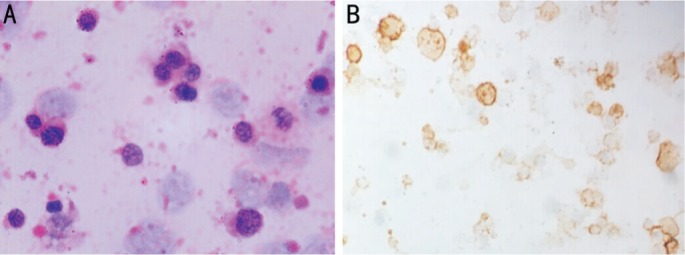

The delay between a positive diagnosis and the onset of ocular or neurological symptoms usually ranges from 4-40mo[23],[28],[42], although more rapid progression may occur[43].The diagnosis of IOL requires a multidisciplinary approach, involving morphological assessment in conjunction with traditional immunocytochemistry and molecular analysis [such as flow cytometry and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis]. Histologic identification remains one of the essential procedures in diagnosing IOL[44]–[45]. Morphologically and immunohistochemically, the typical lymphoma cells are usually with scanty cytoplasm, an elevated nucleus: cytoplasm ratio, round, oval, bean, or irregular shaped nuclei with a coarse chromatin and prominent or multiple nucleoli[46]–[47] (Figure 1A). In B cell lymphoma the predominance of lymphoma cells were identified as CD20, CD79α positive and CD3 negative (Figure 1B, 1C). And in T cell lymphoma, medium to large sized lymphoid cells with atypical nuclei are visualized with HE staining (Figure 2A). While the tumor cells are identified as CD3 positive and CD20 negative (Figure 2B, 2C). Both the two types of IOL are with high Ki-67 positive rate (average >80%) indicates extensive proliferation (Figures 1D, 2D). Specimens can be obtained by fine needle vitreous aspiration or pars plana vitrectomy. And multiple biopsies may be required to reach a definite pathological diagnosis. Removed ocular fluids (via aqueous tap, vitreous tap, or diagnostic vitrectomy) need to be delivered quickly for laboratory analysis, to prevent cell degeneration that can make diagnosis difficult[47]. Furthermore, a negative vitrectomysample is common, sparse number of cells is also the main reason for misdiagnosis. In addition, vitreous specimens contain many reactive T-lymphocytes, necrotic cells, debris, and fibrin that can also confound the identification of malignant cells[46]. Then, retinal or chorioretinal biopsies may be required. Microscopically, the typical lymphoma cells are large B-cell lymphoid cells with scanty cytoplasm, an elevated (nucleus:cytoplasm) ratio, heteromorphic deeply stained nuclei with a coarse chromatin pattern and prominent nucleoli can be seen (Figure 3). Pars plana vitrectomy has several advantages, including improved vision by clearance of vitreous debris and maximizing the sample size[44],[48]–[49], although the lymphoma may extend to the epibulbar space through the sclerotomy port following vitrectomy[50].

Figure 1. Histopathological and immunohistological of IOL origining from B cell.

The atypical cells have pleomorphic nuclei with conspicuous nucleoli and scanty cytoplasm (A, HE staining, 200×). It is positive for CD20 (B, 200×) and negative for CD3 (C, 200×); the high Ki-67 positive rate (average >80%) indicates extensive proliferation (D, 200×).

Figure 2. Histopathological and immunohistological of IOL origining from T cell.

Medium-to-large-sized lymphoid cells with atypical nuclei are visualized with HE staining (A, 200×) and identified as CD3 positive (B, 200×), CD20 negative (C, 200×); the high Ki-67 positive rate (average >80%) indicates extensive proliferation (D, 200×).

Figure 3. Cytology of the vitreous specimen reveals some atypical, large lymphoid cells, with large, deeply stained, irregular nuclei and coarse chromatin (A, 400×), which is identified as CD20 positive (B, 400×).

Molecular analysis detecting immunoglobulin gene rearrangements in the lymphoma cells and ocular cytokine analysis of vitreous fluid show elevated interleukin (IL-10) with an IL-10:IL-6 ratio >1.0 are helpful for the diagnosis, while inflammatory conditions typically show elevated IL-6[17],[51]–[53]. In addition, if the eyes have no function or conservative treatment is impossible, a diagnostic enucleation may become necessary[54]. Flow cytometry can examine cell surface markers and demonstrate monoclonal B-cell populations. IOL is typically comprised of amonoclonal B-cell population with restricted κ or λ chains. A κ:λ ratio of 3 or 0.6 is a highly sensitive marker for lymphoma[55]. PCR has been used to amplify the immunoglobulin heavy chain DNA. In B-cell lymphomas, molecular analysis can detect IgH gene rearrangements, while in T-cell lymphomas, T-cell receptor gene rearrangements can be detected[56]. Detection of the bcl-2 t (14;18) translocation is also an effective method to diagnose IOL. Wallace et al[57] reported that 40 of 72 (55%) PIOL patients expressed the bcl-2 t (14;18) translocation at the major breakpoint region. A PCR analysis of EB virus with aqueous humor might be useful for supporting the diagnosis of intraocular NK-cell lymphoma[58]. Microdissection with a minimum of 15 atypical lymphoid cells has been shown to have a diagnostic efficiency of 99.5% by using PCR[59].

Besides, ophthalmological examinations frequently demonstrate the presence of vitritis, usually in association with infiltrates of the retina and the retinal pigment epithelium. Hyperfluorescense on fundus autofluorescence imaging can demonstrate active sub-retinal pigment epithelium deposits, while hypofluorescent spots can correspond to areas where tumor cells were suspected to have once been[60]. Fluorescein angiography (FA) may show mottling, granularity, and late staining patterns with a characteristic “leopard spotappearance”[23],[32],[34]–[35],[61]. OCT demonstrates hyper reflective lesions at the level of the RPE in PVRL. The valuable diagnostic tools include fundoscopy, FA, OCT, fundus autofluorescence, and fluorescein and indocyanine green angiography. There has been reported that ophthalmological examinations finding had a positive predictive value of 88.9% and a negative predictive value of 85%[32]. In addition, once cerebral lymphoma is suspected, contrast-enhanced cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the best imaging modality. Lesions are often isointense to hypointense on T2-weighted MRI, with variable surrounding edema and a homogeneous and strong pattern of enhancement[62]–[63].

TREATMENT

Due to the rarity of IOL, standard and optimal therapy is not defined. Treatment modalities for IOL include intravitreal chemotherapy, systemic chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, which is used alone or in an appropriate combination. The therapies vary according to the disease degree, the presence or absence of CNS involvement, and performance status of the patients[64]. The current recommendation for the treatment of IOL without CNS or systemic involvement should be limited to local treatment, including intraocular methotrexate and/or ocular radiation in order to minimize systemic toxicities[38]. Ocular irradiation with prophylactic CNS treatment is used to control IOL, maintain vision, and prevent CNS involvement[24]. The average external beam radiation dose is close to 40 Gy, but can range from 30 to 50 Gy[29]. The complications of radiotherapy include radiation retinopathy, vitreous hemorrhage, dry eye syndrome, conjunctivitis, neovascular glaucoma, optic atrophy, punctate epithelial erosions or cataract[29]. While the treatment of the patients with CNS involvement includes a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy[63],[65]. As with systemic chemotherapy, the mainstay of intravitreal chemotherapy is methotrexate[66]. Rituximab is an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody. And intravitreal rituximab is often used to decrease the frequency of methotrexate injections or for methotrexate-resistant IOL[67]–[69]. Initial response was good with clearance of PIOL, but subsequent relapse required intravitreal methotrexateand radiation[67]. Methotrexate can also use alone or in combination with other medications, such as thiotepa and dexamethasone[34],[70]–[72]. High dose methotrexate is the most active drug, producing a response rate of up to 72% when used alone and up to 94%-100% in combinations[73]–[74]. Combined intravitreal methotrexate and systemic high-dosemethotrexate treatment is effective in patients with PIOL[75]. However, polychemotherapy is also associated with higher drug toxicity[29]. In addition, intravitreal chemotherapy with 0.4 mg methotrexate in 0.1 mL achieved local tumor control in relapsed IOL[76]–[77]. Also the intravitreal chemotherapy is a primary treatment in combination with systemic chemotherapy[70]. Drug resistance may occur with repeated injections[78]. For relapsed or refractory PIOL with PCNSL has been treated with intrathecal methotrexate and cytarabine[79]. These treatment decisions are often complex and require personalized treatment for different patients.

PROGNOSIS

IOL is a rare lymphocytic malignancy, the reported mortality rate range between 9% and 81% in follow-up periods, and the survival time is 12-35mo[19],[80]–[82]. However, the reported mortality rate of IOL is very inconsistent because of the rare patient populations, variation in treatment modalities, and the delayed diagnosis. Tumor recurrence is common, and sometimes the existing treatment cannot effectively prevent the local recurrence and the CNS involvement. The prognosis depends on the following aspects: 1) whether the CNS is involved. A trend toward better survival was seen among patients with isolated ocular presentation[83]–[84]. Moreover, the IOL patients with CNS involvement are almost died in the short term. Neuroimaging is important for the patients after treatment since the IOL patients carry a risk for recurrence or CNS involvement[85]; 2) histopathologic type is another important factors. Generally T cell type has poorer prognosis than B cell type; 3) treatment opportunity, early treatment after onset of symptoms may improve the prognosis for a better visual outcome[86]. In PCNSL, median survival of patients treated with radiotherapy alone or chemotherapy plus radiotherapy ranges from 10 to 16mo[38]; 4) the vision and survival rates are both poor in recurrent patients. Due to the rarity of the disease, there is often misdiagnosis, delay in diagnosis, and mismanagement of IOL.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, IOL often masquerades as intraocular inflammation resulting in misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis, with subsequent inappropriate management and high mortality rates. Patients with suspected IOL should undergo cytopathologic examination of vitreal fluid or vitrectomy before therapy. On the ocular cytokine levels, mainly IL-10:IL-6 ratio and molecular analysis can provide useful supplementary data for the diagnosis. Once IOL is diagnosed, all patients are required to be examined the subtle neurological symptoms and signs with the oncologist. Meanwhile, neuroimaging is performed to detect any evidence of CNS involvement. Optimal therapy for IOL is considered a great challenge to the clinical. Intravitreal chemotherapy with more than one agent may be proved to be useful in controlling the ocular disease. When the CNS involved, methotrexate-based systemic chemotherapy with external beam radiotherapy should be undertaken. Because of the rarity of this disease, multicenter studies are needed to obtain optimized treatment methods in order to get better vision and prognosis.

METHOD OF LITERATURE SEARCH

PubMed (1970 to end of 2016) database was searched using the search terms IOL, PIOL and SIOL. Removing duplicate articles, excluding articles that clearly related to extraocular lymphoma, and removing foreign language papers provided a total of 86 unique articles in English.

Acknowledgments

Foundation: Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.30371515).

Conflicts of Interest: Tang LJ, None; Gu CL, None; Zhang P, None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buggage RR, Chan CC, Nussenblatt RB. Ocular manifestations of central nervous system lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2001;13(3):137–142. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200105000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fredrick DR, Char DH, Ljung BM, Brinton DA. Solitary intraocular lymphoma as an initial presentation of widespread disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107(3):395–397. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070010405034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy-Clarke GA, Buggage RR, Shen D, Vaughn LO, Chan CC, Davis JL. Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type-1 associated T-cell leukemia/lymphoma masquerading as necrotizing retinal vasculitis. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(9):1717–1722. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldey SH, Stern GA, Oblon DJ, Mendenhall NP, Smith LJ, Duque RE. Immunophenotypic characterization of an unusual T-cell lymphoma presenting as anterior uveitis. A clinicopathologic case report. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107(9):1349–1353. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020419047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saga T, Ohno S, Matsuda H, Ogasawara M, Kikuchi K. Ocular involvement by a peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102(3):399–402. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030317027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunyor AP, Harper CA, O'Day J, McKelvie PA. Ocular-central nervous system lymphoma mimicking posterior scleritis with exudative retinal detachment. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(10):1955–1959. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00342-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaput F, Amer R, Baglivo E, Touitou V, Kozyreff A, Bron D, Bodaghi B, LeHoang P, Bergstrom C, Grossniklaus HE, Chan CC, Pe'er J, Caspers LE. Intraocular T-cell lymphoma: clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2016;22:1–10. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2016.1139733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan CC. Molecular pathology of primary intraocular lymphoma. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2003;101:275–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coupland SE, Damato B. Understanding intraocular lymphomas. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36(6):564–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mulay K, Narula R, Honavar SG. Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2015;63(3):180–186. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.156903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy EK, Bhatia P, Evans RG. Primary orbital lymphomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;15(5):1239–1241. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(88)90210-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho BJ, Yu HG. Risk factors for intraocular involvement in patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. J Neurooncol. 2014;120(3):523–529. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1581-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeAngelis LM, Yahalom J, Thaler HT, Kher U. Combined modality therapy for primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(4):635–643. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.4.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan CC, Rubenstein JL, Coupland SE, Davis JL, Harbour JW, Johnston PB, Cassoux N, Touitou V, Smith JR, Batchelor TT, Pulido JS. Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: a report from an International Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma Collaborative Group symposium. Oncologist. 2011;16(11):1589–1599. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freeman LN, Schachat AP, Knox DL, Michels RG, Green WR. Clinical features, laboratory investigations, and survival in ocular reticulum cell sarcoma. Ophthalmology. 1987;94(12):1631–1639. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(87)33256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hochberg FH, Miller DC. Primary central nervous system lymphoma. J Neurosurg. 1988;68(6):835–853. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.68.6.0835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimura K, Usui Y, Goto H. Clinical features and diagnostic significance of the intraocular fluid of 217 patients with intraocular lymphoma. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2012;56(4):383–389. doi: 10.1007/s10384-012-0150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan CC, Sen HN. Current concepts in diagnosing and managing primary vitreoretinal (intraocular) lymphoma. Discov Med. 2013;15(81):93–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berenbom A, Davila RM, Lin HS, Harbour JW. Treatment outcomes for primary intraocular lymphoma: implications for external beam radiotherapy. Eye (Lond) 2007;21(9):1198–1201. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buettner H, Bolling JP. Intravitreal large-cell lymphoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68(10):1011–1015. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peterson K, Gordon KB, Heinemann MH, DeAngelis LM. The clinical spectrum of ocular lymphoma. Cancer. 1993;72(3):843–849. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930801)72:3<843::aid-cncr2820720333>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qualman SJ, Mendelsohn G, Mann RB, Green WR. Intraocular lymphomas. Natural history based on a clinicopathologic study of eight cases and review of the literature. Cancer. 1983;52(5):878–886. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830901)52:5<878::aid-cncr2820520523>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cassoux N, Merle-Beral H, Leblond V, Bodaghi B, Miléa D, Gerber S, Fardeau C, Reux I, Xuan KH, Chan CC, LeHoang P. Ocular and central nervous system lymphoma: clinical features and diagnosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2000;8(4):243–250. doi: 10.1076/ocii.8.4.243.6463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Margolis L, Fraser R, Lichter A, Char DH. The role of radiation therapy in the management of ocular reticulum cell sarcoma. Cancer. 1980;45(4):688–692. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800215)45:4<688::aid-cncr2820450412>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, Flandrin G, Muller-Hermelink HK, Vardiman J, Lister TA, Bloomfield CD. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting-Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(12):3835–3849. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.12.3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen DF, Herbort CP, Tuaillon N, Buggage RR, Egwuagu CE, Chan CC. Detection of Toxoplasma gondii DNA in primary intraocular B-cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 2001;14(10):995–999. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan CC. Primary intraocular lymphoma: clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Lymphoma. 2003;4(1):30–31. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9655(11)70005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman PM, McKelvie P, Hall AJ, Stawell RJ, Santamaria JD. Intraocular lymphoma: a series of 14 patients with clinicopathological features and treatment outcomes. Eye (Lond) 2003;17(4):513–521. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang CS, Yeh S, Bergstrom CS. Diagnostic vitrectomy for primary intraocular lymphoma: when, why, how? Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2014;54(2):155–171. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0000000000000022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gill MK, Jampol LM. Variations in the presentation of primary intraocular lymphoma: case reports and a review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;45(6):463–471. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(01)00217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hormigo A, DeAngelis LM. Primary ocular lymphoma: clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Lymphoma. 2003;4(1):22–29. doi: 10.3816/clm.2003.n.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fardeau C, Lee CP, Merle-Beral H, Cassoux N, Bodaghi B, Davi F, Lehoang P. Retinal fluorescein, indocyanine green angiography, and optic coherence tomography in non-Hodgkin primary intraocular lymphoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147(5):886–894. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levy-Clarke GA, Byrnes GA, Buggage RR, Shen DF, Filie AC, Caruso RC, Nussenblatt RB, Chan CC. Primary intraocular lymphoma diagnosed by fine needle aspiration biopsy of a subretinal lesion. Retina. 2001;21(3):281–284. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200106000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Velez G, Chan CC, Csaky KG. Fluorescein angiographic findings in primary intraocular lymphoma. Retina. 2002;22(1):37–43. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meleth AD, Sen HN. Use of fundus autofluorescence in the diagnosis and management of uveitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2012;52(4):45–54. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e3182662ee9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hedayatfar A, Phaik Chee S. Presumptive primary intraocular lymphoma presented as an intraocular mass involving the optic nerve head. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2012;2(1):49–51. doi: 10.1007/s12348-011-0045-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanavi MR, Soheilian M, Bijanzadeh B, Peyman GA. Diagnostic vitrectomy (25-gauge)in a case with intraocular lymphoma masquerading as bilateral granulomatous panuveitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010;20(4):795–798. doi: 10.1177/112067211002000426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grimm SA, McCannel CA, Omuro AM, Ferreri AJ, Blay JY, Neuwelt EA, Siegal T, Batchelor T, Jahnke K, Shenkier TN, Hall AJ, Graus F, Herrlinger U, Schiff D, Raizer J, Rubenstein J, Laperriere N, Thiel E, Doolittle N, Iwamoto FM, Abrey LE. Primary CNS lymphoma with intraocular involvement: International PCNSL Collaborative Group Report. Neurology. 2008;71(17):1355–1360. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327672.04729.8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abusamra K, Oray M, Ebrahimiadib N, Lee S, Anesi S, Foster CS. Intraocular lymphoma: descriptive data of 26 patients including clinico-pathologic features, vitreous findings, and treatment outcomes. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2016;20:1–6. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2016.1193206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin TC, Lin PY, Wang LC, Chen SJ, Chang YM, Lee SM. Intraocular involvement of T-cell lymphoma presenting as inflammatory glaucoma, neurotrophic keratopathy, and choroidal detachment. J Chin Med Assoc. 2014;77(7):385–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levy-Clarke GA, Greenman D, Sieving PC, Byrnes G, Shen D, Nussenblatt R, Chan CC. Ophthalmic manifestations, cytology, immunohistochemistry, and molecular analysis of intraocular metastatic T-cell lymphoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(3):285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grimm SA, Pulido JS, Jahnke K, Schiff D, Hall AJ, Shenkier TN, Siegal T, Doolittle ND, Batchelor T, Herrlinger U, Neuwelt EA, Laperriere N, Chamberlain MC, Blay JY, Ferreri AJ, Omuro AM, Thiel E, Abrey LE. Primary intraocular lymphoma: an International Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma Collaborative Group Report. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(11):1851–1855. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vogel MH, Font RL, Zimmerman LE, Levine RA. Reticulum cell sarcoma of the retina and uvea. Report of six cases and review of the literature. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968;66(2):205–215. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(68)92065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Char DH, Kemlitz AE, Miller T. Intraocular biopsy. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2005;18(1):177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ohc.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mastropasqua R, Thaung C, Pavesio C, Lightman S, Westcott M, Okhravi N, Aylward W, Charteris D, da Cruz L. The role of chorioretinal biopsy in the diagnosis of intraocular lymphoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(6):1127–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coupland SE, Bechrakis NE, Anastassiou G, Foerster AM, Heiligenhaus A, Pleyer U, Hummel M, Stein H. Evaluation of vitrectomy specimens and chorioretinal biopsies in the diagnosis of primary intraocular lymphoma in patients with Masquerade syndrome. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;241(10):860–870. doi: 10.1007/s00417-003-0749-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karma A, von Willebrand EO, Tommila PV, Paetau AE, Oskala PS, Immonen IJ. Primary intraocular lymphoma: improving the diagnostic procedure. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(7):1372–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gonzales JA, Chan CC. Biopsy techniques and yields in diagnosing primary intraocular lymphoma. Int Ophthalmol. 2007;27(4):241–250. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9065-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Margolis R. Diagnostic vitrectomy for the diagnosis and management of posterior uveitis of unknown etiology. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008;19(3):218–224. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3282fc261d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cursiefen C, Holbach LM, Lafaut B, Heimann K, Kirchner T, Naumann GO. Oculocerebral non-Hodgkin's lymphoma with uveal involvement: development of an epibulbar tumor after vitrectomy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(10):1437–1440. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.10.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davis JL. Intraocular lymphoma: a clinical perspective. Eye (Lond) 2013;27(2):153–162. doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rajagopal R, Harbour JW. Diagnostic testing and treatment choices in primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. Retina. 2011;31(3):435–440. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31820a6743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sugita S, Takase H, Sugamoto Y, Arai A, Miura O, Mochizuki M. Diagnosis of intraocular lymphoma by polymerase chain reaction analysis and cytokine profiling of the vitreous fluid. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2009;53(3):209–214. doi: 10.1007/s10384-009-0662-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trudeau M, Shepherd FA, Blackstein ME, Gospodarowicz M, Fitzpatrick P, Moffatt KP. Intraocular lymphoma: report of three cases and review of the literature. Am J Clin Oncol. 1988;11(2):126–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davis JL, Miller DM, Ruiz P. Diagnostic testing of vitrectomy speciments. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(5):822–829. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shen DF, Zhuang Z, LeHoang P, Böni R, Zheng S, Nussenblatt RB, Chan CC. Utility of microdissection and polymerase chain reaction for the detection of immunoglobulin gene rearrangement and translocation in primary intraocular lymphoma. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(9):1664–1669. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)99036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wallace DJ, Shen D, Reed GF, Miyanaga M, Mochizuki M, Sen HN, Dahr SS, Buggage RR, Nussenblatt RB, Chan CC. Detection of the bcl-2 t(14;18) translocation and proto-oncogene expression in primary intraocular lymphoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(7):2750–2756. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tagawa Y, Namba K, Ogasawara R, Kanno H, Ishida S. A case of mature natural killer-cell neoplasm manifesting multiple choroidal lesions: primary intraocular natural killer-cell lymphoma. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2015;6(3):380–384. doi: 10.1159/000442018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Y, Shen D, Wang VM, Sen HN, Chan CC. Molecular biomarkers for the diagnosis of primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12(9):5684–5697. doi: 10.3390/ijms12095684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ishida T, Ohno-Matsui K, Kaneko Y, Tobita H, Shimada N, Takase H, Mochizuki M. Fundus autofluorescence patterns in eyes with primary intraocular lymphoma. Retina. 2010;30(1):23–32. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181b408a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garweg JG, Wanner D, Sarra GM, Altwegg M, Loosli H, Kodjikian L, Halberstadt M. The diagnostic yield of vitrectomy specimen analysis in chronic idiopathic endogenous uveitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2006;16(4):588–594. doi: 10.1177/112067210601600414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kuker W, Nagele T, Korfel A, Heckl S, Thiel E, Bamberg M, Weller M, Herrlinger U. Primary central nervous system lymphomas (PCNSL): MRI features at presentation in 100 patients. J Neurooncol. 2005;72:169–177. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-3390-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoang-Xuan K, Bessell E, Bromberg J, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary CNS lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: guidelines from the European Association for Neuro-Oncology. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):e322–332. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sagoo MS, Mehta H, Swampillai AJ, Cohen VM, Amin SZ, Plowman PN, Lightman S. Primary intraocular lymphoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014;59(5):503–516. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stubiger N, Kakkassery V, Gundlach E, Winterhalter S, Pleyer U. Diagnostics and treatment of primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. Ophthalmologe. 2015;112(3):223–230. doi: 10.1007/s00347-014-3204-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang YC, Jou JR. Intravitreal injections of methotrexate in treatment of primary central nervous system lymphoma with intraocular involvement. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2016;32(12):638–639. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Itty S, Olson JH, O'Connell DJ, Pulido JS. Treatment of primary intraocular lymphoma (PIOL) has involved systemic, intravitreal or intrathecal chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. Retina. 2009;29(3):415–416. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318196b1f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim H, Csaky KG, Chan CC, Bungay PM, Lutz RJ, Dedrick RL, Yuan P, Rosenberg J, Grillo-Lopez AJ, Wilson WH, Robinson MR. The pharmacokinetics of rituximab following an intravitreal injection. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82(5):760–766. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kitzmann AS, Pulido JS, Mohney BG, Baratz KH, Grube T, Marler RJ, Donaldson MJ, O'Neill BP, Johnston PB, Johnson KM, Dixon LE, Salomao DR, Cameron JD. Intraocular use of rituximab. Eye (Lond) 2007;21(12):1524–1527. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fishburne BC, Wilson DJ, Rosenbaum JT, Neuwelt EA. Diagnosis and treatment of primary CNS lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: guidelines from the European Association for Neuro-Oncology. Intravitreal methotrexate as an adjunctive treatment of intraocular lymphoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115(9):1152–1156. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160322009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Smet MD, Vancs VS, Kohler D, Solomon D, Chan CC. Diagnosis and treatment of primary CNS lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: guidelines from the European Association for Neuro-Oncology. Intravitreal chemotherapy for the treatment of recurrent intraocular lymphoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83(4):448–451. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.4.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Smet MD. Management of non-Hodgkin's intraocular lymphoma with intravitreal methotrexate. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2001;279:91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tempescul A, Pradier O, Marianowski-Cochard C, Ianotto JC, Berthou C. Combined therapy associating systemic platinum-based chemotherapy and local radiotherapy into the treatment of primary intraocular lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2011;90(9):1117–1118. doi: 10.1007/s00277-010-1139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Korfel A, Schlegel U. Diagnosis and treatment of primary CNS lymphoma. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(6):317–327. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ma WL, Hou HA, Hsu YJ, Chen YK, Tang JL, Tsay W, Yeh PT, Yang CM, Lin CP, Tien HF. Clinical outcomes of primary intraocular lymphoma patients treated with front-line systemic high-dose methotrexate and intravitreal methotrexate injection. Ann Hematol. 2016;95(4):593–601. doi: 10.1007/s00277-015-2582-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.de Smet MD, Stark-Vancs V, Kohler DR, Smith J, Wittes R, Nussenblatt RB. Intraocular levels of methotrexate after intravenous administration. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121(4):442–444. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70444-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang JK, Yang CM, Lin CP, Shan YD, Lo AY, Tien HF. An Asian patient with intraocular lymphoma treated by intravitreal methotrexate. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2006;50(5):474–478. doi: 10.1007/s10384-005-0327-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sen HN, Chan CC, Byrnes G, Fariss RN, Nussenblatt RB, Buggage RR. Intravitreal methotrexate resistance in a patient with primary intraocular lymphoma. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2008;16(1):29–33. doi: 10.1080/09273940801899764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mason JO, Fischer DH. Intrathecal chemotherapy for recurrent central nervous system intraocular lymphoma. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(6):1241–1244. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Akpek EK, Ahmed I, Hochberg FH, Soheilian M, Dryja TP, Jakobiec FA, Foster CS. Intraocular-central nervous system lymphoma: clinical features, diagnosis, and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(9):1805–1810. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90341-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dunleavy K, Wilson WH. Primary intraocular lymphoma: current and future perspectives. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47(9):1726–1727. doi: 10.1080/10428190600674339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Isobe K, Ejima Y, Tokumaru S, Shikama N, Suzuki G, Takemoto M, Tsuchida E, Nomura M, Shibamoto Y, Hayabuchi N. Treatment of primary intraocular lymphoma with radiation therapy: a multi-institutional survey in Japan. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47(9):1800–1805. doi: 10.1080/10428190600632881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kim MM, Dabaja BS, Medeiros J, Kim S, Allen P, Chevez-Barrios P, Gombos DS, Fowler N. Survival outcomes of primary intraocular lymphoma: a single-institution experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39(2):109–113. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee S, Kim MJ, Kim JS, Oh SY, Kim SJ, Kwon YH, Chung IY, Kang JH, Yang DH, Kang HJ, Yoon DH, Kim WS, Kim HJ, Suh C. Intraocular lymphoma in Korea: the consortium for improving survival of lymphoma (CISL) study. Blood Res. 2015;50(4):242–247. doi: 10.5045/br.2015.50.4.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jahnke K, Thiel E, Bechrakis NE, Willerding G, Kraemer DF, Fischer L, Korfel A. Ifosfamide or trofosfamide in patients with intraocular lymphoma. J Neurooncol. 2009;93(2):213–217. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9761-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Frenkel S, Hendler K, Siegal T, Shalom E, Pe'er J. Intravitreal methotrexate for treating vitreoretinal lymphoma: 10 years of experience. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(3):383–388. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.127928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]