Abstract

Introduction:

Abiraterone and enzalutamide were approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2011 and 2012 to treat men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Most men with mCRPC are > 65 years of age and thus eligible for Medicare Part D. We conducted a study to better understand the early dissemination of these drugs across the United States using national Medicare Part D data.

Methods:

We evaluated the number of prescriptions for abiraterone and enzalutamide by provider specialty and hospital referral region (HRR) using Medicare Part D and Dartmouth Atlas data. We categorized HRRs by abiraterone and enzalutamide prescriptions, adjusted for prostate cancer incidence, and examined factors associated with regional variation using multilevel regression models.

Results:

Among providers who wrote the majority of prescriptions for abiraterone or enzalutamide in 2013 (n = 2,121), 87.5% were medical oncologists, 3.3% were urologists, and 9.2% were other provider specialties. Among prescribers, approximately 30% were responsible for three quarters of the claims for abiraterone and 20% were responsible for more than half the claims for enzalutamide. Some HRRs demonstrated low-prescribing rates despite average medical oncology and urology physician workforce density. Our multilevel model demonstrated that regional factors potentially influenced variation in care.

Conclusion:

The majority of prescriptions written for abiraterone and enzalutamide through Medicare Part D in 2013 were written by a minority of providers, with marked regional variation across the United States. Better understanding of the early national dissemination of these effective but expensive drugs can help inform strategies to optimize introduction of new, evidence-based mCRPC treatments.

INTRODUCTION

The rapid expansion of cancer therapeutics over the past decade raises hope that a growing menu of oral agents will translate into improved access to care and patient outcomes. However, novel oral treatments are expensive, creating pressure on patients and payers, and initial indications are typically restricted. Alongside changing clinical guidelines, factors unrelated to patients or their disease inevitably foster practice variation (eg, provider specialty, geography, access to care).1-9 Although treatment should vary on the basis of patient and disease factors for appropriate use, treatment on the basis of nonclinical factors may lead to inefficient and low-value care, as well as worse cancer-related outcomes.

The evolving management of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) presents an ideal opportunity to investigate the dissemination of novel, oral cancer therapies and the specialists prescribing these drugs. Two novel therapies, abiraterone and enzalutamide, are Food and Drug Administration–approved oral drugs that improved progression-free and overall survival for men with mCRPC in randomized trials.10-13 Although both medical oncologists and urologists treat mCRPC, the extent to which providers in each specialty adopt these novel oral therapies remains unclear. Moreover, guidelines recommend that treatment decisions involving these drugs take into account multiple patient and disease factors.14,15 Whether other factors, such as provider specialty, workforce, and region of the country, influenced the early dissemination of these agents is also unclear.

For these reasons, we used national Medicare Part D claims and the Dartmouth Atlas to investigate who prescribed abiraterone and enzalutamide across the United States in 2013, variation in early prescribing patterns, and the extent to which prescription of these drugs may be driven by nonclinical factors, such as region and provider specialty. We also examined the extent to which different regions of the country adopted these drugs, taking into consideration the medical oncology and urology workforce. Describing the early dissemination of abiraterone and enzalutamide will help inform future dissemination strategies of novel oral therapies and identify areas of potential overuse or underuse of these medications.

METHODS

Data Sources

The 2013 Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data: Part D Prescriber Public Use File (PUF) is a publicly available database with data by provider on drug utilization and cost for every prescription filled through Medicare Part D in 2013. Two thirds of Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in Medicare Part D in 2013, providing information for over 35 million beneficiaries. The dataset includes address and specialty for providers imported from the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System. To protect patient confidentiality, information about the exact claim count and cost of drugs was not included for providers who prescribed 10 or fewer claims for a drug. Ultimately, the PUF includes information from 86.8% of claims and 78.1% of total costs among beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Part D.

Drug utilization and cost in the dataset are based on information from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Prescription Drug Event Standard Analytic File, which includes 100% of final-action claims (where all claim adjustments have been resolved). The number of prescriptions written, including refills, and number of days dispensed were reported for each drug prescribed by providers who prescribed > 10 prescriptions of that drug in 2013. The total drug cost is the sum of the amount paid by the Part D plan, the patient, government subsidies, and any other third-party payers and included the cost of the medication itself, dispensing fees, sales tax, and administration fees.

We used the Dartmouth Atlas to help characterize dissemination of these drugs. The Dartmouth Atlas Project is a publicly available dataset that uses Medicare claims from beneficiaries to illustrate geographic variability in health care. The Atlas divides the country into 306 hospital referral regions (HRRs), which are considered different tertiary care health care markets. The Dartmouth Atlas contains information on prostate cancer incidence for each HRR, defined as the number of men diagnosed with prostate cancer per 1,000 male beneficiaries eligible for Medicare Parts A and B. Because prostate cancer incidence could be influenced by screening patterns and therefore may not be a direct reflection of mCRPC, we also calculated case fatality rates (deaths from cancer per patient diagnosed) for prostate cancer across the country using prostate cancer incidence and fatality rates from the American Cancer Society.16 We assumed that the distribution of prostate cancer incidence would accurately reflect the distribution of patients with mCRPC if the case fatality rate was similar across states. Because prostate cancer is a disease of older men (median age at diagnosis, 67 years),17 we also expected that the Medicare beneficiary population would accurately reflect the majority of patients with prostate cancer because patients enrolled in Medicare are over the age of 65 years. Last, the Dartmouth Atlas also reports the relevant physician workforce within each HRR (ie, number of medical oncologists and urologists per 1,000 Medicare beneficiaries). We used these data to additionally examine and adjust prescription rates.

Study Population

Our study sample included providers in the PUF identified by their National Provider Identifier number who wrote a prescription for either abiraterone or enzalutamide in 2013. To understand prescribing at the provider level, we grouped the providers into six categories using the specialty provided in the database: urologist; medical oncologist; primary care provider; advanced-practice provider; radiation oncology; and other (Appendix Table A1, online only). For providers initially identified as internal medicine, family practice, or other, we performed a robust online search using https://npiregistry.cms.hhs.gov/ and, in rare instances in which specialty was not apparent, the www.healthgrades.com Web site, to confirm the provider specialty. Among providers initially listed as internal medicine, family practice, or other, we recategorized 79.5% into the medical oncologist specialty and 1% into urology, whereas the remaining 19.5% remained as primary care provider or other.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome for this study was the number of claims for abiraterone and enzalutamide over the incidence of prostate cancer within each HRR, yielding a claims rate. Because the claims were listed by provider, we were able to cross-walk provider ZIP codes to the Dartmouth Atlas HRRs to determine how many claims were made for each drug within HRRs adjusted for prostate cancer incidence. Abiraterone was approved by the Food and Drug Administration to be used postdocetaxel, 16 months earlier than enzalutamide, and its approved indication expanded to predocetaxel in 2013. Enzalutamide was only approved to be used in the postdocetaxel setting in 2013. Therefore, we expected to observe different dissemination patterns when mapping out the HRR claims rates for abiraterone and enzalutamide, specifically, that the number of claims for abiraterone would outnumber the claims for enzalutamide overall, and within the average HRR. To additionally examine variation in HRR claims rates, we divided the HRRs into quartiles on the basis of the claims rate for abiraterone and enzalutamide within the HRR. A priori, we termed those HRRs in the highest quartile of claims rates for both drugs as early adopting and HRRs in the lowest quartile for both of these drugs as low-access.

Our secondary outcome for this study was the distribution of prescriptions by provider type. Because medical oncologists and urologists were expected to prescribe the majority of these drugs, we limited the provider-level analysis to these two specialties and compared the claims prescribed by each specialty and any outlier prescribers. We also used the aggregated number of claims to determine the number of low-prescribing physicians for whom we did not have detailed information and were able to determine the proportion of providers responsible for their proportion of the claims made in 2013. We then determined the 2013 total drug costs as a secondary outcome by summing all claim costs in the dataset. To validate that the number of total days dispensed and total number of claims was complete, we calculated the average monthly supply for each drug because typically these drugs are filled in 1-month supplies.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each provider by drug. We used Pearson correlation coefficients to determine whether a provider who prescribed one of the two drugs had a high likelihood of prescribing the other. Next, we log-transformed the claims rates for abiraterone and enzalutamide for each HRR because of their skewed distributions and plotted each on a scatter plot to examine the distribution patterns of early-adopting and low-access HRRs. Last, we used multilevel regression modeling to determine the extent to which variation in adjusted prescription rates was primarily based at the provider or regional level. This modeling approach accounts for potential correlations in the data (ie, multiple providers within an HRR) by incorporating an HRR-level random effect in the model. We used the random intercept model with no explanatory variables (ie, crude model) as our primary model. We calculated the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) corresponding to the estimated variance components from the crude model to determine the portion of the total variation in adjusted prescription rates that occurred between HRRs. We calculated the 95% CI for ICC with a bootstrap method. We then included provider workforce variables at the HRR level and case fatality rate at the state levels to test whether the adjusted prescription rates seemed to be driven by clinical burden or other regional factors. The probability of a type I error was set at 0.05, and all testing was two-sided. All analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R software (version 3.2.2; R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

This study was determined to be Not Regulated by the University of Michigan Internal Review Board because the investigators did not interact with or obtain identifiable private information about human participants.

RESULTS

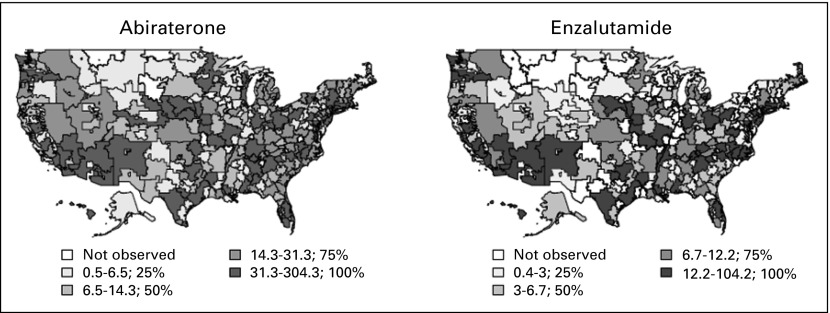

In 2013, there were 51,168 claims for abiraterone and 16,941 claims for enzalutamide made through Medicare Part D that were prescribed by providers who wrote at least 10 prescriptions. Each drug was dispensed in an average of a 30.4-day supply, consistent with a monthly prescription rate. When categorizing providers into HRRs, we found that 11 of the 306 HRRs did not have providers who prescribed > 10 prescriptions for either abiraterone or enzalutamide. Figure 1 illustrates the variation in prescribing rates for abiraterone and enzalutamide. There was no significant correlation between the urology workforce and the claims rate for abiraterone (r = 0.06; P = .31) or enzalutamide (r = 0.10; P = .10), indicating that HRRs with more urologists did not necessarily prescribe more abiraterone and enzalutamide for patients with prostate cancer. However, there was a weak positive correlation between the medical oncology workforce and the claims rate for both abiraterone (r = 0.30; P < .01) and enzalutamide (r = 0.28; P < .01), indicating the possibility that the presence of more medical oncologists in a given HRR may lead to more prescriptions per patient with prostate cancer. Even though the use of abiraterone and enzalutamide varied across HRRs and visually by states, the disease burden across states was similar, with an average case fatality rate of 0.15 and a standard deviation of 0.02 (range, 0.11-0.20).

Fig 1.

Regional variation in the early national dissemination of abiraterone and enzalutamide according to hospital referral region. The median claims rates (claims per prostate cancer incidence) for abiraterone and enzalutamide for each hospital referral region were divided into quartiles to illustrate variation in prescription patterns across the United States.

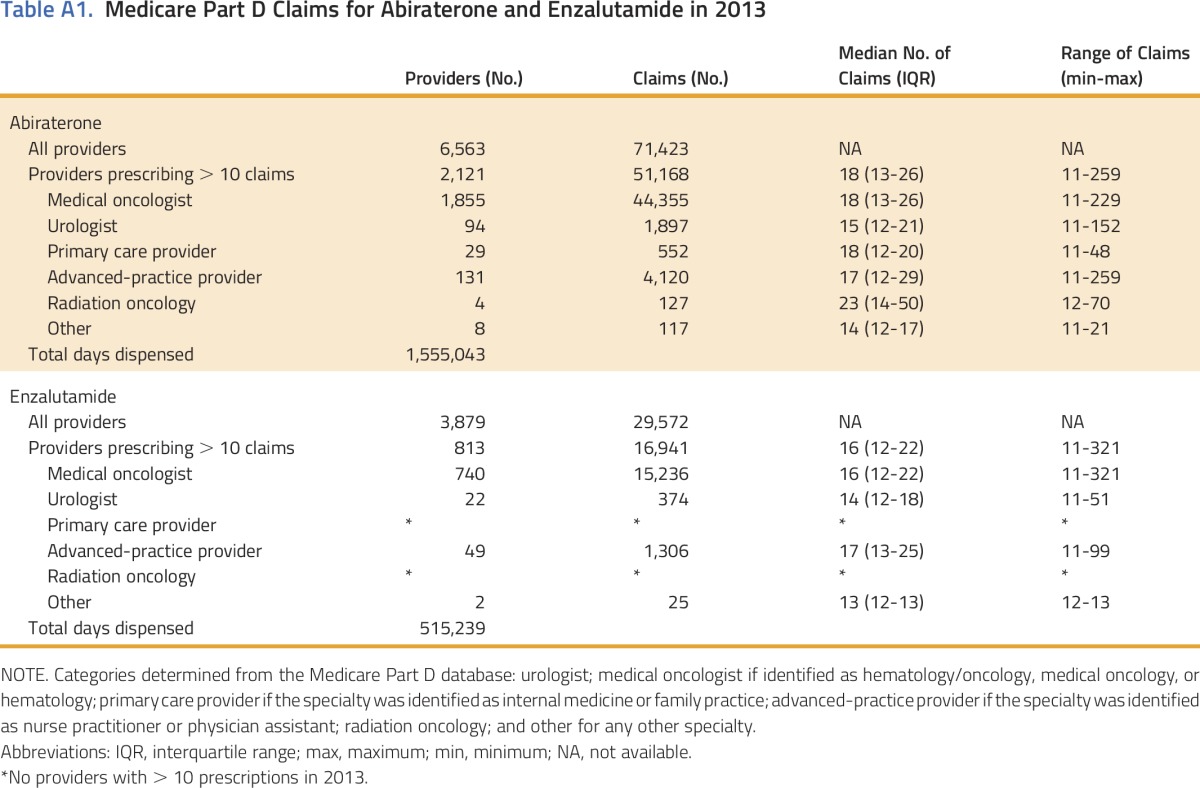

Within the PUF, we identified 10,469 medical oncologists and 9,640 urologists. The majority of providers who wrote any prescription for abiraterone or enzalutamide wrote 10 or fewer prescriptions. (Table A1, online only). There were 2,162 medical oncologists (21%) and 109 urologists (1%) who prescribed > 10 prescriptions for either abiraterone or enzalutamide. Among those who prescribed > 10 prescriptions for abiraterone or enzalutamide, medical oncologists were responsible for 87.5% of the prescriptions, urologists were responsible for 3.3%, and the remainder accounted for 9.2% (Table A1).

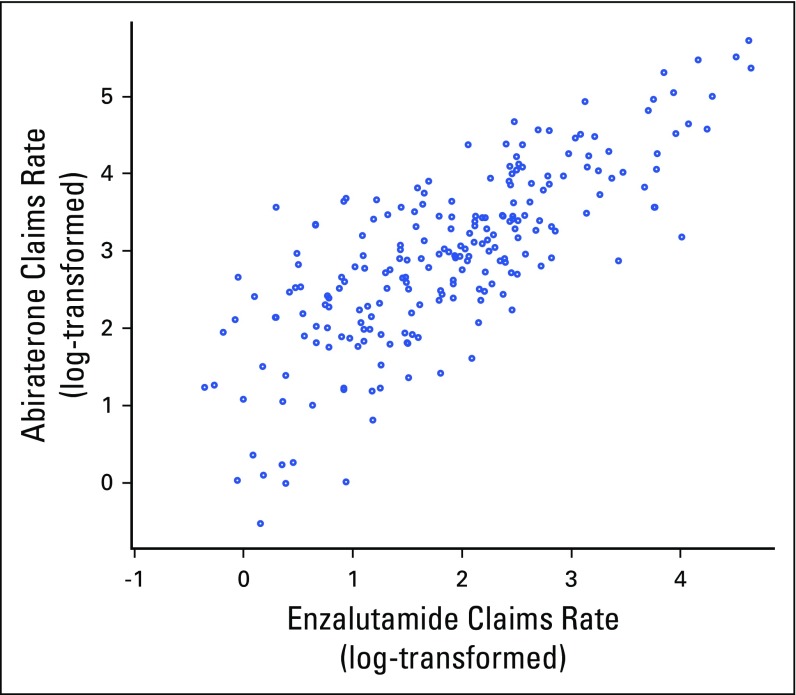

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of HRRs by plotting their log-transformed claims rates for each drug. There were 54 HRRs (18%) that had claims rates for both drugs in the top quartile, which we termed early adopting, and 44 HRRs (14%) that had claims rates for both drugs in the lowest quartile, which we termed low-access. The median claims rates for enzalutamide and abiraterone in the early-adopting HRRs were 59 and 18, respectively, in contrast to two and zero, respectively, in the low-access HRRs.

Fig 2.

Prescribing patterns for abiraterone and enzalutamide across hospital referral regions. Because of the skewed distribution of the data, a log scale was used. The 11 hospital referral regions with no claims listed for either drug are not shown.

Within medical oncology and urology, we found that a minority of providers was responsible for the majority of abiraterone and enzalutamide claims (Fig 3). For example, three quarters of the abiraterone prescriptions written by medical oncologists and urologists were prescribed by only 30% of those providers prescribing the drug. We observed a similar pattern for enzalutamide prescriptions. There was a strong correlation for total prescriptions written for abiraterone and enzalutamide among medical oncologists (r = 0.82; P < .001), indicating that medical oncologists who were likely to prescribe one drug were likely to prescribe the other. However, there was no significant correlation of the prescriptions written for the two drugs among urologists (r = –0.10; P = .79).

Fig 3.

Proportions of prescription claims for abiraterone and enzalutamide among advanced prostate cancer care providers. This figure does not include claims for non-medical oncologist or urologist providers who prescribed > 10 prescriptions for either drug.

Our crude multilevel model indicated that 13% of variation in claims rates (ICC = 0.13; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.16) was attributable to differences at the HRR level. After adjustment for state prostate cancer case fatality rates and regional provider workforce variables, the ICC did not change (ICC = 0.13; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.17), indicating other regional factors were potentially influencing variation in care.

The total cost of abiraterone and enzalutamide prescriptions to Medicare Part D and its beneficiaries in 2013 was $701.2 million. This amount is likely to be a small fraction of the current annual cost as more providers prescribe these new drugs.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrated marked regional variation in the early national dissemination of abiraterone and enzalutamide through the Medicare Part D drug program. Regional differences in prescription rates persisted, even after adjustment for prostate cancer incidence and provider workforce. Given the variation in prescribing practices after accounting for prostate cancer incidence and state fatality rates, other factors related to providers and regions (eg, subspecialization, specialty pharmacy connections) may be implicated rather than disease severity. Whether abiraterone or enzalutamide were prescribed was not correlated with urology workforce and was weakly correlated with medical oncologist workforce density, suggesting that a patient’s access to a physician may not be a big influence on whether these prescriptions are being written. We also identified different regional dissemination patterns, including early-adopting and low-access regions, raising the possibility that patients residing in low-access regions may be undertreated for mCRPC. Interestingly, the majority of providers who wrote a prescription for abiraterone or enzalutamide wrote fewer than 11 prescriptions in the entire year, and a minority of providers was responsible for most of the prescriptions. This high-volume provider phenomenon suggests an additional level of specialization, with potentially increased comfort or experience among providers prescribing these drugs.

Characterizing variation in the early dissemination patterns for these novel treatments is an important first step toward optimizing care for patients with mCRPC. Addressing modifiable factors leading to any unwarranted variation may help improve access to care (eg, physician comfort prescribing these new oral cancer drugs), especially given that provider and hospital factors can be more influential than patient and disease factors when it comes to making treatment decisions.8,18-22 Physicians adopt new medications and adhere to guidelines at varying rates23-27 and with varying comfort levels,3,28-31 which may explain our findings indicating that a small proportion of urology and medical oncology providers were responsible for the majority of claims. This subspecialization within providers is not uncommon in oncology and may present a unique strategy to promote consistent, high-quality care among selected high-volume providers.

Better understanding of regional variation in the use of mCRPC therapeutics could have implications for providers, policy-makers, and, ultimately, patients. Urologists widely prescribe androgen deprivation therapy to treat metastatic prostate cancer, but most patients were traditionally referred to medical oncologists when they became castration-resistant for patients to begin chemotherapy. Now that newer therapies that can be given orally and a urology professional society (American Urological Association) encourages their use,32 we expect that more urologists will begin prescribing abiraterone and enzalutamide with practices that may differ from those of medical oncologists. Nonetheless, studies to measure whether population-based outcomes are improved among high-volume providers and early-adopting practices are warranted. For policy-makers, it is important to understand the use of these expensive novel therapies to provide the best value-based care for Medicare beneficiaries because spending is only expected to climb in upcoming years as providers become more accustomed to using these medications.33

We acknowledge that a limitation of our study is aggregated data at the provider level, precluding an evaluation of patient-level factors (eg, race, age, socioeconomic status, comorbid conditions, disease status) that influence prescribing patterns. Therefore, it is possible that low-rate prescribers for both drugs may have patients with financial constraints and that high-rate prescribers served a patient population with more resources. However, describing the prescription landscape and potential gaps in care is a first step before investigating other factors that may influence the patterns we observed. In addition, although we had data on the incidence of prostate cancer within an HRR, we did not have information on the number of patients with prostate cancer seen by each provider. Nonetheless, understanding differences at the HRR level allows us to better define regional signatures for future investigation. Although data for the aggregated total providers, claims, and cost were available, we were not able to analyze characteristics of the providers who wrote fewer than 11 prescriptions for either drug in the PUF. However, we expected that low-prescribing providers would be spread across HRRs and that their low-volume data are unlikely to affect the final results. In addition, the large number of providers writing few prescriptions further supports our conclusion that the majority of prescriptions are being written by a minority of providers. Finally, the claims do not specify the associated cancer type or severity. Because these drugs are only approved for the treatment of mCRPC, we expect that nearly all prescriptions were written for patients with mCRPC.

In conclusion, we found that early dissemination patterns for abiraterone and enzalutamide varied geographically, across HRRs. Medical oncologists were the majority prescribers for novel oral therapeutics for mCRPC, but within specialties, there was apparent subspecialization, indicating that a minority of providers were responsible for the majority of prescriptions. Future work will need to investigate patient factors associated with early adoption and determine whether patterns from this study persist with more recent data. This study may help guideline committees and national organizations anticipate how best to introduce new treatments to a limited workforce so that all patients have the opportunity to benefit from evidence-based care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge Ryan Blake for his work on validating provider specialties. Supported in part by a VA Health Services Research and Development award (No. CDA 12-171) to T.A.S. and National Cancer Institute Grant (No. T32-CA180984) to T.B. D.C.M. and J.J.G. are supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute (Grant No. R01 CA174768). B.K.H. is supported by a Research Scholar Grant (No. RSGI-13-323-01-CPHPS) from the American Cancer Society and funding from a National Institute on Aging Grant (No. R01 AG 048071).

Appendix

Table A1.

Medicare Part D Claims for Abiraterone and Enzalutamide in 2013

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Megan E.V. Caram, Tudor Borza, Hye-Sung Min, Jennifer J. Griggs, Ted A. Skolarus

Financial support: David C. Miller, Ted A. Skolarus

Administrative support: David C. Miller, Ted A. Skolarus

Provision of study materials or patients: Ted A. Skolarus

Collection and assembly of data: Megan E.V. Caram, Tudor Borza, Hye-Sung Min, Ted A. Skolarus

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Early National Dissemination of Abiraterone and Enzalutamide for Advanced Prostate Cancer in Medicare Part D

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jop/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Megan E.V. Caram

No relationship to disclose

Tudor Borza

No relationship to disclose

Hye-Sung Min

No relationship to disclose

Jennifer J. Griggs

No relationship to disclose

David C. Miller

Other Relationship: Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, National Cancer Institute

Brent K. Hollenbeck

No relationship to disclose

Bhramar Mukherjee

No relationship to disclose

Ted A. Skolarus

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1. Baicker K, Chandra A, Skinner JS, et al: Who you are and where you live: How race and geography affect the treatment of medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) VAR33-VAR44, 2004 (suppl variation) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Birkmeyer JD, Finks JF, O’Reilly A, et al. Surgical skill and complication rates after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1434–1442. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1300625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.du Bois A, Rochon J, Pfisterer J, et al. Variations in institutional infrastructure, physician specialization and experience, and outcome in ovarian cancer: A systematic review. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:422–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Variation in hospital mortality associated with inpatient surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1368–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0903048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillner BE, Smith TJ, Desch CE. Hospital and physician volume or specialization and outcomes in cancer treatment: Importance in quality of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2327–2340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.11.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGuire KJ, Harrast J, Herkowitz H, et al. Geographic variation in the surgical treatment of degenerative cervical disc disease: American Board of Orthopedic Surgery Quality Improvement Initiative; part II candidates. Spine. 2012;37:57–66. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318212bb61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Malley AS, Pham HH, Schrag D, et al. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations for COPD and pneumonia: The role of physician and practice characteristics. Med Care. 2007;45:562–570. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180408df8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wennberg DE, Dickens JD, Jr, Biener L, et al. Do physicians do what they say? The inclination to test and its association with coronary angiography rates. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:172–176. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-5025-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, Steinman MA, Kaplan CM. Geographic variation in outpatient antibiotic prescribing among older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1465–1471. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE, et al. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:424–433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:138–148. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Prostate Cancer Version 1.2015. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Basch E, Loblaw DA, Oliver TK, et al. Systemic therapy in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Cancer Care Ontario clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3436–3448. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2011. American Cancer Society, July 2016 https://old.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-029771.pdf.

- 17.Brawley OW. Prostate cancer epidemiology in the United States. World J Urol. 2012;30:195–200. doi: 10.1007/s00345-012-0824-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birkmeyer JD, Reames BN, McCulloch P, et al. Understanding of regional variation in the use of surgery. Lancet. 2013;382:1121–1129. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61215-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birkmeyer JD, Sharp SM, Finlayson SR, et al. Variation profiles of common surgical procedures. Surgery. 1998;124:917–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laycock WS, Siewers AE, Birkmeyer CM, et al. Variation in the use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy for elderly patients with acute cholecystitis. Arch Surg. 2000;135:457–462. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weinstein JN, Bronner KK, Morgan TS, et al: Trends and geographic variations in major surgery for degenerative diseases of the hip, knee, and spine. Health Aff (Millwood)VAR81-VAR89, 2004 (suppl variation) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Wennberg DE, Kellett MA, Dickens JD, et al. The association between local diagnostic testing intensity and invasive cardiac procedures. JAMA. 1996;275:1161–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grol R. Successes and failures in the implementation of evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice. Med Care. 2001;39(suppl 2):II46–II54. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108002-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denig P, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, Wesseling H, et al. Impact of clinical trials on the adoption of new drugs within a university hospital. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;41:325–328. doi: 10.1007/BF00314961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lublóy Á. Factors affecting the uptake of new medicines: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:469. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones MI, Greenfield SM, Bradley CP. Prescribing new drugs: Qualitative study of influences on consultants and general practitioners. BMJ. 2001;323:378–381. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7309.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dybdahl T, Andersen M, Kragstrup J, et al. General practitioners’ adoption of new drugs and previous prescribing of drugs belonging to the same therapeutic class: A pharmacoepidemiological study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60:526–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollack CE, Soulos PR, Gross CP. Physician’s peer exposure and the adoption of a new cancer treatment modality. Cancer. 2015;121:2799–2807. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flowers CR, Fedewa SA, Chen AY, et al. Disparities in the early adoption of chemoimmunotherapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1520–1530. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eddy DM. Variations in physician practice: The role of uncertainty. Health Aff (Millwood) 1984;3:74–89. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.3.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cookson MS, Roth BJ, Dahm P, et al. Castration-resistant prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. J Urol. 2013;190:429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wennberg JE, Fisher ES, Skinner JS. Geography and the debate over Medicare reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;(suppl web exclusives):W96-W114. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]