Abstract

Background

Studies of interspecies interactions are inherently difficult due to the complex mechanisms which enable these relationships. A model system for studying interspecies interactions is the marine hyperthermophiles Ignicoccus hospitalis and Nanoarchaeum equitans. Recent independently-conducted ‘omics’ analyses have generated insights into the molecular factors modulating this association. However, significant questions remain about the nature of the interactions between these archaea.

Methods

We jointly analyzed multiple levels of omics datasets obtained from published, independent transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics analyses. DAVID identified functionally-related groups enriched when I. hospitalis is grown alone or in co-culture with N. equitans. Enriched molecular pathways were subsequently visualized using interaction maps generated using STRING.

Results

Key findings of our multi-level omics analysis indicated that I. hospitalis provides precursors to N. equitans for energy metabolism. Analysis indicated an overall reduction in diversity of metabolic precursors in the I. hospitalis—N. equitans co-culture, which has been connected to the differential use of ribosomal subunits and was previously unnoticed. We also identified differences in precursors linked to amino acid metabolism, NADH metabolism, and carbon fixation, providing new insights into the metabolic adaptions of I. hospitalis enabling the growth of N. equitans.

Conclusions

This multi-omics analysis builds upon previously identified cellular patterns while offering new insights into mechanisms that enable the I. hospitalis—N. equitans association.

Introduction

Benefits from systems-level analysis of transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data have yielded fruitful insights into complex systems and provide a more comprehensive analysis of cellular activity [1–5]. In addition to analyzing single cell types or single organisms, systems-level ‘omics’ data analysis is particularly beneficial when attempting to better characterize interspecies relationships and associations. While systems biology research has made great strides in strengthening our understanding of complex biological systems, detailed knowledge of fundamental molecular interaction mechanisms, cellular communication, and nutrient exchange within microbial communities is still limited. Multi ‘omics’ studies provide additional insights into critical cellular pathways and mechanisms of interspecies communication within a microbial community. These insights are however not readily accessible through single ‘omics’ data interpretation. Recent studies employing systems-level analyses have demonstrated the potential of these methods to better understand the fundamental properties of microbial communities in soil, water treatment plants, the human body, and the nature of interspecies interactions [6–9].

A microbial system whose complex cellular organization is lacking in comprehensive understanding of its molecular networks, and would benefit from a systems-level multi-omics analysis to better understand the nature of its interspecies interactions, is the archaeal system comprised of Ignicoccus hospitalis and Nanoarchaeum equitans. I. hospitalis is a hyperthermophilic chemolithoautotroph isolated from hydrothermal marine vents located off the coast of Iceland. This organism derives its energy from the reduction of elemental sulfur to hydrogen sulfide, and utilizes carbon dioxide as its sole carbon source [10]. I. hospitalis has one of the smallest genomes of any free-living organism, with just under 1,500 protein-coding genes, and is the only identified and characterized host for the small, hyperthermophilic archaeal organism, N. equitans [11,12]. The N. equitans genome is too small to support life independently, containing only 556 protein-coding genes [13], and notably lacking enzymes catalyzing bioenergetic pathways essential for independent growth. N. equitans is thus incapable of survival without physical attachment to and co-existence with I. hospitalis [11,14,15]. Furthermore, while the attachment of N. equitans slows the growth of I. hospitalis, causing early entry into stationary phase, N. equitans does not appear to have significant deleterious effects on I. hospitalis’s physiology and survival [14]. Physical attachment and co-culture growth appear to satisfy N. equitans’s requirement for anabolic precursors, whereby the import of metabolites and energy-rich small molecules from I. hospitalis compensates for cellular processes that cannot be independently supported by the cellular components encoded within N. equitans’s genome. However, the molecular mechanisms enabling transfer or exchange of nutrients and cellular precursors between the two species have remained elusive [16,17]. A similar nanoarchaeal symbiotic system recently isolated from a terrestrial geothermal system indicates that this type of interspecies interactions is not restricted to Ignicocccus and Nanoarchaeum species, and may be widespread in high temperature environments [18].

Recent transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics analyses have focused independently on better understanding the nature of the inter-species interactions between I. hospitalis and N. equitans. These studies have characterized molecular differences between cell cultures of I. hospitalis grown in the absence or in co-culture with N. equitans [12,15,16,19]. Through these efforts, insights into energy transfer, growth processes, and metabolic coupling have been identified, suggesting that N. equitans exploits I. hospitalis primarily to obtain molecules that can be used as a source of metabolic energy rather than for N. equitans biomass production. While these studies have been informative, much remains to be elucidated about the molecular mechanisms that enable this unusual inter-species association and the overall physiological coupling between these two organisms. Systems-wide analysis of multi-omics datasets presents an opportunity to strengthen our understanding of the molecular mechanisms driving the inter-species interactions shared between I. hospitalis—N. equitans.

In this study, we have utilized data generated from multiple functional genomics platforms, i.e. transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, to specifically uncover interaction mechanisms that were not apparent in previous studies that analyzed the data from each omics technology independently. Using the bioinformatics resources, Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) and Search Tool for Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING), transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics datasets recorded on I. hospitalis and N. equitans were combined and analyzed at the systems-level [20,21]. DAVID is a web-based tool designed to extract biological meaning from large lists of genes and proteins by identifying functionally related groups through enrichment analysis, and has been widely used because of its versatility in handling various data formats as well as its efficient analysis of large datasets [22–24]. STRING complements DAVID by generating interaction maps highlighting and visualizing relationships between genes, proteins, and metabolites based on genomic context, experimental evidence, conserved gene co-expression, and text mining [25]. By combining transcriptomics, metabolomics, and proteomics data into an integrated dataset, a better understanding of the biological processes characterizing the I. hospitalis–N. equitans association has been achieved.

Methods

Omics Data Sets

The datasets used in this study were generated from separate transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics studies performed previously. Detailed experimental methods are reported in the original publications [16,19], and a table of experimental details for each ‘omics’ study, outlining the number of replicates, is included in supplementary material (Supplementary Table 1). Briefly, each of these ‘omics’ studies were performed on microbial cells collected from I. hospitalis-only cultures and I. hospitalis–N. equitans co-cultures at late log phase of growth [19]. For transcriptomics analysis, cell pellets from each culture were homogenized in Trizol and purified using a PureLinkRNA Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). RNA was converted to cDNA using a ds-cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen) and cDNA abundance was assessed using a high-density gene expression microarray (1plex, 385k) manufactured by Roche NimbleGen Inc. All arrays were performed in triplicate and were scanned with a Surescan HR DNA Microarray Scanner and quantified using NimbleScan 2.6 [19]. 1404 I. hospitalis transcripts were identified and expression abundances were normalized using Loess normalization [19]. The gene abundances for both cultures were compared for differentially expressed gene levels by an analysis of variance and were corrected for multiple comparisons (data accessible at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE57033). These abundances were used to calculate fold changes for each gene between the two cultures [19].

Proteomics data were generated from intracellular protein analyses using online 2D-LC-MS/MS of label-free peptides pre-digested with trypsin in duplicate for each culture as reported in Gianonne et al. (2011, 2014). Peptides were identified with Myrimatch [26] using the combined I. hospitalis-N.equitans FASTA protein database (GenBank CP000816.1, AE017199.1), and semi-quantitative differential analysis was based on spectral counting as originally reported [15]. Proteins encoded by 1154 genes of the I. hospitalis genome were identified. Normalized spectral abundance factor (NSAF) values for each protein were calculated based on number of spectra collected and protein length, and each NSAF value was normalized over average total spectra count over all sample sets (data accessible at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3149612/bin/pone.0022942.s003.xls). These normalized spectral count values were used to calculate fold changes in protein abundance between the I. hospitalis-only and I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-cultures [15].

To generate metabolite profiles, metabolites were extracted from cell cultures grown in triplicate using an aqueous MeOH extraction and analyzed by LC-MS and 1H 1D NMR [16]. For LC-MS analysis, normal and reverse LC phase chromatography was employed using an UHPLC system connected to a Q-TOF mass spectrometer run in positive ion mode. The data were processed using Masshunter Qualitative software (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) and analyzed using software package MZmine 2.10. NMR metabolite analyses were performed on biological duplicate samples, and 1D 1H NMR spectra were acquired using a Bruker 600 MHz (1H Larmor frequency) AVANCE III solution NMR spectrometer. Resulting 1D 1H NMR spectra were processed and analyzed using the Chenomx™ software version 7.6 (Chenomx Inc., Edmonton, AB, Canada) [16]. Separate analyses of the MS and NMR metabolomics data resulted in the unambiguous identification of 35 metabolites in the I. hospitalis-N. equitans culture and 39 in the I. hospitalis-only culture, and when combined, resulted in doubling the number of unambiguous metabolite IDs (data accessible at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4529127/table/T1/) [16]. Fold changes were calculated using mass spectral peak areas (MS) or metabolite concentrations (NMR) for each detected metabolite.

Enrichment Analysis using DAVID

Proteins, transcripts, and metabolites identified with a fold change of 1.5 or higher when comparing I. hospitalis cultures alone versus the I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-cultures were analyzed using DAVID (https://david.ncifcrf.gov) to identify enriched groups of functionally similar components as described by Huang et al. [27]. The combined dataset contained 807 transcripts / proteins / metabolites that were higher in abundance in the I. hospitalis-only samples and 604 in the I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture samples, all with adjusted p-values smaller than 0.05. DAVID connects each data input with a biological annotation based on gene ontology and biochemical pathway association, and then identifies groups that are overrepresented in the dataset based on X2 and Fisher’s exact tests. This program uses genes and proteins as input data. As such, metabolic information was incorporated by using proteins involved in producing and/or processing each metabolite as proxies. The enzymes involved in processing metabolites of interest were identified using the Biocyc database for I. hospitalis [28]. Output of the DAVID analysis contains a list of functional groups with enrichment scores, p-values, as well as Benjamini p-values and false discovery rates to account for multiple comparisons between all features [27]. Through this process, we obtained lists of functionally-related groups that were enriched in the I. hospitalis-only culture and the I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture. An enrichment score cutoff with a p-value < 0.05 was applied.

Interaction Maps using STRING

The enriched groups from DAVID were then run through the STRING (http://string-db.org/) software to obtain network visualizations identifying the relationships between cellular components based on genomic characteristics [genes occur in similar genetic context in different species (genomic neighborhood), gene products are fused in the genome (gene fusion), proteins occur or have similar function in the same metabolic pathway (gene co-occurrence), genes are co-expressed (conserved co-expression)], high-throughput omics experimental evidence, and previous knowledge, i.e. databases and text mining [20,25,27]. All networks retained for analysis were constructed using the high confidence criterion as defined by STRING as the association score “S” > 0.75 [25]. Resulting clusters of predicted associations were thus produced and spatially arranged according to high confidence scores as defined in STRING with no further manipulation of the clusters.

Results

To gain a better understanding of the cellular mechanisms mediating the interactions between I. hospitalis and N. equitans, previously acquired transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics datasets for I. hospitalis grown alone and in co-culture with N. equitans were combined to undertake an extensive, systems-level multi-omics analysis [16,19]. DAVID analysis yielded a list of functionally related groups that were enriched in the data for each type of I. hospitalis and I. hospitalis-N. equitans cell cultures. These enriched groups were then used to construct interaction maps in STRING connecting proteins and genes based on genome proximity (i.e. encoded on same operon), related biochemical pathways, co-expression, and text mining [25,27].

The STRING-generated network maps revealed several significant observations with respect to inter-species interactions between I. hospitalis and N. equitans that were not previously identified in the single ‘omics’ platform analyses (Figures 1 and 2). In each of these maps, the largest and most connected cluster in the network is a group of strongly associated ribosomal proteins (Figure 3). While both clusters contain small and large subunit ribosomal proteins, each cluster is comprised of subsets of ribosomal genes and proteins specific to each type of cell culture (Table 1). Rather than representing a simple increase or decrease in ribosomal gene transcription levels, these cluster patterns are in all likelihood evidence of “ribosomal tuning” and differential usage of specific ribosomal proteins [29–32]. A comparison of I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-cultures to I. hospitalis-only cell cultures showed that 8 ribosomal protein mRNAs and 5 ribosomal proteins had fold changes greater than 10. The prominence and distinctness of the two ribosomal clusters clearly distinguish the I. hospitalis-only culture from the I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture.

Figure 1. I. hospitalis-N. equitans Co-culture Interaction Map.

Interactions between up-regulated transcripts, proteins, and metabolites resulting from STRING analysis of the I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture as compared to the I. hospitalis-only culture. Clustering based on connections shown in legend. Data used to generate interaction maps includes proteins, transcripts, and metabolites with fold changes ≥ 1.5 and p-values < 0.05. Network maps were constructed under high confidence (>0.75).

Figure 2. I. hospitalis Culture Interaction Map.

Interactions between up-regulated transcripts, proteins, and metabolites resulting from STRING analysis of the I. hospitalis-only culture as compared to the I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture. Clustering based on connections shown in legend. Data used to generate interaction maps includes proteins, transcripts, and metabolites with fold changes ≥ 1.5 and p-values < 0.05. Network maps were constructed under high confidence (>0.75).

Figure 3. Ribosomal Protein Clusters.

Up-regulated ribosomal transcripts/proteins found in the I. hospitalis only culture and the I. hospitalis—N. equitans co-culture STRING interaction maps. Blue nodes denote up-regulated transcripts and red nodes denote up-regulated proteins. Only transcripts/proteins with a fold change > 1.5 and p-value < 0.05 were used to generate each interaction map.

Table 1. Identification of Up-regulated Ribosomal Proteins.

Gene identifiers and annotations of up-regulated ribosomal genes/proteins. Ribosomal protein clusters were found in the I. hospitalis culture and I. hospitalis—N. equitans co-culture STRING interaction maps (Figure 3).

| I. hospitalis Culture | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gene Identifier | Annotation | Type |

| Igni_1383 | Translation elongation factor 2 | t |

| Igni 0184 | LSU ribosomal protein L18AE | t |

| Igni 1344 | Peptide chain release factor subunit 1 | p |

| Igni_1411 | LSU ribosomal protein L5P | t |

| Igni_0767 | SSU ribosomal protein S8E | t |

| Igni_1182 | LSU ribosomal protein L10P | t,p |

| Igni_1044 | Signal recognition particle subunit FFH/SRP54 | t |

| Igni_0768 | Signal recognition particle, subunit SRP19 | p |

| Igni_0185 | LSU ribosomal protein L13P | t |

| Igni_0287 | LSU ribosomal protein L31E | t,p |

| Igni_0724 | LSU ribosomal protein L24E | t,p |

| Igni_0001 | Translation initiation factor ealF-5B | t,p |

| Igni_1177 | Signal recognition particle-docking protein FtsY | t |

| Igni_1181 | LSU ribosomal protein L1P | t |

| Igni_0677 | SSU ribosomal protein S6E | t |

| Igni_0590 | SSU ribosomal protein S3P | t |

| Igni_0186 | SSU ribosomal protein S9P | t |

| Igni_0907 | LSU ribosomal protein L15E | t |

| Igni_0588 | SSU ribosomal protein S19P | t |

| Igni_0193 | SSU ribosomal protein S25E | t |

| Igni_0290 | SSU ribosomal protein S26E | t,p |

| Igni_1128 | Translation initiation factor 5A (elF-5A) | t |

| Igni_0863 | 30S ribosomal protein S2Ae | t |

| Co-culture | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gene Identifier | Annotation | Type |

| Igni_1199 | Protein translocase subunit secY/sec61 alpha | p |

| Igni_0103 | SSU ribosomal protein S27E | t |

| Igni_0860 | SSU ribosomal protein S15P | t |

| Igni_0838 | LSU ribosomal protein L40E | t,p |

| Igni_0188 | SSU ribosomal protein S2P | t |

| Igni_0249 | SSU ribosomal protein S7P | p |

| Igni_0180 | SSU ribosomal protein S13P | t |

| Igni_1181 | LSU ribosomal protein L1P | p |

| Igni_1412 | SSU ribosomal protein S14P | p |

| Igni_1276 | SSU ribosomal protein S5P | t |

| Igni_0589 | LSU ribosomal protein L22P | p |

| Igni_1407 | SSU ribosomal protein S17P | p |

| Igni_0979 | LSU ribosomal protein L37E | p |

| Igni_0286 | 50S ribosomal protein L39E | p |

Note: Gene/proteins are listed by I. hospitalis gene identifiers with corresponding annotations. Type refers to the omic level: transcript (t), protein (p), or metabolite (m).

The interaction maps also highlighted prominent clusters associated with amino acid metabolic pathways. Enrichment analyses of the I. hospitalis-only cell cultures included pathways involved in amino acid charging of transfer RNAs for incorporation of specific amino acids into polypeptide chains, and involved the biosynthetic pathways for proline, histidine, methionine, valine, tyrosine, tryptophan, glycine, aspartate, and serine (Figure 2 and Table 2). In contrast, I. hospitalis -N. equitans co-cultures showed enrichments in the data for metabolic pathways involving asparagine, aspartate, glutamine, and phenylalanine (Figure 1 and Table 2). The DAVID analysis also identified enzyme enrichments in the co-culture corresponding to the up-regulation of leucine and isoleucine biosynthetic pathways. These clusters thus revealed significant differences in amino acid requirements when I. hospitalis is grown in co-culture with N. equitans compared to when I. hospitalis is grown in the absence of N. equitans.

Table 2. Identification of Amino Acid Metabolism Clusters.

Gene identifiers and annotations of up-regulated amino acid metabolism clusters found in the I. hospitalis culture and I. Hospitalis—N. equitans co-culture STRING interaction maps (Figures 1 and 2).

| I. hospitalis Culture | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | ||

| Gene Identifier | Annotation | Type |

| Igni_0313 | Anticodon-binding domain-containing protein | t |

| Igni_0879 | Histidyl-tRNA synthetase | t,p |

| L-Histidine | m | |

| Igni_0586 | Undecaprenyl pyrophosphate synthetase | p |

| Igni_0362 | Prolyl-tRNA synthetase | p |

| L-Proline | m | |

| Igni_0928 | Arginyl-tRNA synthetase | t |

| Igni_1155 | Methionyl-tRNA synthetase | |

| L-Methionine | m | |

| Igni_0220 | Valyl-tRNA synthetase | |

| L-Valine | m | |

| Igni_0347 | Tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase | |

| L-Tyrosine | m | |

| Cluster 2 | ||

| Igni_0843 | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole-succinocarboxamide synthase | T |

| L-Aspartate | m | |

| Igni_1091 | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase | |

| Glycine | m | |

| Igni_0165 | Phosphoribosylamine--glycine ligase | t |

| Glycine | m | |

| Igni_1252 | Phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synthase subunit II | t |

| Igni_0844 | Hypothetical protein | t,p |

| Igni_0303 | ACT domain-containing protein | t |

| Igni_0305 | Hypothetical protein | t |

| Igni_1100 | Tryptophan synthase subunit beta | |

| L-Serine | m | |

| L-Tryptophan | m | |

| Igni_1301 | Tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase | |

| L-Tryptophan | m | |

| Igni_0242 | HAD family hydrolase | t,p |

| Igni_0311 | Phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine cyclo-ligase | p |

| Co-culture | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gene Identifier | Annotation | Type |

| Igni_1228 | L-glutamine synthetase | p |

| Igni_1400 | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase small subunit | p |

| Igni_0621 | N-acetylglutamate kinase/N2-acetyl-L-aminoadipate kinase | t |

| Igni_0570 | Asparagine synthase | p |

| L-asparagine | m | |

| Igni_1349 | Aspartate dehydrogenase | p |

| Igni_0641 | Quinolinate synthetase A | p |

| Igni_0569 | Hypothetical protein | p |

| Igni_0199 | Aspartate kinase | |

| L-Aspartyl-4-Phosphate | m | |

| Igni_1227 | Phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase, alpha subunit | |

| L-Phenylalanine | m | |

| Igni_0396 | Ser-tRNA(Thr) hydrolase | p |

| Igni_1155 | Methionyl-tRNA synthetase | t,p |

| Igni_0480 | S-layer-like domain-containing protein | p |

| Igni_0479 | Hypothetical protein | p |

| Igni_0441 | Hypothetical protein | t |

| Igni_0440 | Glycosyl transferase family protein | p |

| Igni_0155 | SNO glutamine amidotransferase | p |

Note: Gene/proteins are listed by Ignicoccus gene identifiers with corresponding annotations. Metabolites are listed below enzymes that utilize or produce them. Type refers to the omic level: transcript (t), protein (p), or metabolite (m).

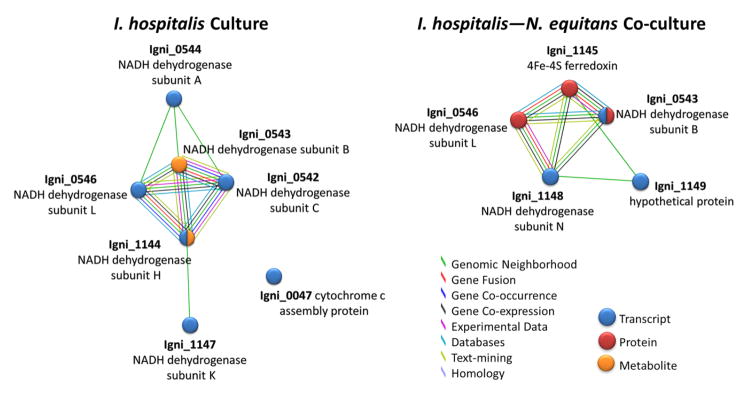

Energy production pathways were also highlighted in the interaction maps, including NADH metabolism and carbon flow through catabolic reactions. Differences in NADH metabolism between the I. hospitalis-only and the I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture samples were highlighted by differences in enzyme components of NADH dehydrogenases and ferredoxins (Figure 4). Inversely correlated patterns of gene and protein expression result in gene identifiers appearing in both the I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture and the I. hospitalis-only culture clusters. Carbon assimilation in I. hospitalis occurs through an autotrophic dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle that was characterized by Huber et al. [33]. This pathway employs reduced metabolic intermediates for efficient CO2 fixation. A cluster of enzymes responsible for the catalysis of intermediary steps of this CO2 fixation pathway was identified in the interaction map of the I. hospitalis-only cell cultures (Table 3, Supplementary Figure 1). Examination of up-regulated transcripts/high protein levels in the I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture compared to the I. hospitalis-only culture confirmed that very few of the enzymes of the dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate pathway were represented. Since this pathway was not highlighted in either DAVID or STRING for the I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture samples, this suggests that carbon may be diverted from the dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle of I. hospitalis to generate intermediates needed for N. equitans growth and survival (Figure 5). The findings regarding NADH metabolism and carbon fixation illustrate differences in energy production between the two types of cell growth.

Figure 4. NADH Metabolism Clusters.

Up-regulated genes/proteins/metabolites comprising the NADH metabolism clusters found in the I. hospitalis only culture and I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture STRING interaction maps. Individual Ignicoccus gene identifiers and annotations are shown for each cluster. Blue, red, and orange nodes denote up-regulated transcripts, proteins, and metabolites respectively, each with a fold change > 1.5 and p-value < 0.05.

Table 3. Identification of Carbon Fixation Cluster.

Gene identifiers and annotations of the carbon fixation (dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle) cluster identified in the I. hospitalis culture STRING interaction map (Figure 2).

| I. hospitalis Culture | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gene Identifier | Annotation | Type |

| Igni_0944 | N2-acetyl-L-lysine aminotransferase | t |

| N2-Acetyl-L-Lysine | m | |

| Igni_0945 | Hypothetical protein | t |

| Igni_0445 | Succinate dehydrogenase iron-sulfur subunit | m |

| Igni_0085 | Succinyl-CoA synthetase (ADP-forming) alpha subunit | t |

| Igni_0086 | Succinyl-CoA synthetase (ADP-forming) beta subunit | t |

| Succinate | m | |

| Igni_0315 | Acetylornithine deacetylase | p |

| L-Ornithine | m | |

| Igni_0363 | Hypothetical protein | t |

| Igni_1361 | Glucokinase | p |

| Igni_0415 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | t |

| Igni_0678 | Fumarase | |

| Fumarate | m | |

| Igni_1079 | Deoxyribose-phosphate aldolase | t,p |

| Igni_0257 | Acyl-coenzyme A synthetase/AMP-(fatty) acid ligase-like protein | t |

| Igni_0256 | AMP-dependent synthetase and ligase | t,p |

| Igni_0983 | Isopropylmalate/citramalate/homocitrate synthase | p |

| Igni_1256 | Pyruvate/ketoisovalerate oxidoreductase, gamma subunit | t |

| Igni_0728 | N-acetyl-gamma-glutamyl-phosphate reductase | t |

| Igni_1387 | Ornithine carbamoyltransferase | t |

| L-Ornithine | m | |

| L-Citrulline | m | |

| Igni_0171 | Glutamine–fructose-6-phosphate transaminase | t |

| Igni_1430 | Argininosuccinate lyase | t |

| Fumarate | m | |

| Igni_0635 | Argininosuccinate synthase | |

| L-Citrulline | m | |

Note: Gene/proteins are listed by Ignicoccus gene identifiers with corresponding annotations. Metabolites are listed below enzymes that utilize or produce them. Type refers to the omic level: transcript (t), protein (p), or metabolite (m).

Figure 5. Cellular processes modulating I. hospitalis and N. equitans association.

This figure integrates multi-level omics data into a map of the biomolecular and metabolic processes in I. hospitalis affected by growth of N. equitans (green triangle, increasing; red triangle, decreasing; yellow circle, no significant change). This figure incorporates previously identified features of this interspecies interaction (black arrows) with the insights enhanced or new to this study (blue arrows). Data presented in this figure is focused on the metabolism of I. hospitalis.

Functional themes, as identified in the DAVID and STRING analyses, emphasize cellular changes occurring when I. hospitalis was grown by itself or in co-culture with N. equitans (Table 4). The I. hospitalis-only cell cultures reveal enrichment of proteins catalyzing a broad range of cellular activities including nucleotide metabolism, gene transcription, membrane transport, energy production, and protein translation. In contrast, regulated pathways in the I. hospitalis–N. equitans co-cultures appear dominated by proteins involved in membrane transport and energy production, including those regulating gene transcription and protein translation processes as presented above. The cellular processes modulating the association of I. hospitalis and N. equitans are summarized in Figure 5, which builds upon previous knowledge and includes the additional insights gained here and described above. Integrated analyses of the multi-omics data thus permit a broader global assessment of cellular processes, drawing attention to metabolic enzymes necessary for energy production in I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-cultures, consistent with previously reported transcriptomics and proteomics analyses [19].

Table 4. Overview of Cellular Activity.

Themes of cellular activity in the I. hospitalis culture and I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture based on DAVID and STRING analyses using transcripts, proteins, and metabolites with a fold change > 1.5 and p-value < 0.05.

| I. hospitalis Themes | Transcripts | Metabolites | Proteins | Network Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide Metabolism | ||||

| Purine Ribonucleotide Binding | 56 | |||

| Nucleotide/Nucleoside/Nucleobase Metabolic Process | 25 | 5 | X | |

| Transcription | ||||

| RNA polymerase | X | |||

| Transcription factors/Nucleoplasm | 3 | X | ||

| Helicase Activity | 7 | 2 | ||

| Membrane Transport and Energy Production | ||||

| Pyrophosphatase Activity (Nucleoside-triphosphatase Activity), Mg Binding | 31 | 7 | ||

| Transporter Activity | 24 | X | ||

| Energy Metabolism | 5 | X | ||

| GTP Binding | 9 | 1 | 2 | X |

| Amino Acid Metabolism | ||||

| Amino Acid Binding, Precursor Amino Add Synthesis | 5 | 10 | X | |

| Ribosomal Structure | 22 | 6 | X | |

| tRNA Synthetases | 2 | 6 | 4 | X |

| Co-culture Themes | Transcripts | Metabolites | Proteins | Network Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription | ||||

| DNA Binding, RNA Polymerase | 6 | 12 | X | |

| Membrane Transport and Energy Production | ||||

| 4Fe-4S Cluster/Transition Metal Binding (e-carry) | 6 | 6 | 32 | X |

| ATP-ase/ABC Transporter Activity | 20 | |||

| Energy Coupled H+ Transport | 6 | |||

| Transport/Localization | 10 | X | ||

| Phosphorus Metabolic Process | 7 | 13 | ||

| Energy Metabolism | 5 | X | ||

| Amino Acid Metabolism | ||||

| Cellular Amino Acid & Derivative Process | 16 | 10 | ||

| Ribosomal Structure | 8 | 8 | X | |

| Valine, Leucine, and Isoleucine Biosynthesis | 4 | 1 | 2 | |

Discussion

Application of a systems-wide approach to analyze multi-level omics datasets generated supporting evidence and strengthened biological trends observed in previous studies [15,16,19]. The study also generated novel insights into the molecular mechanisms forming the basis of the I. hospitalis-N. equitans association. The data analyses presented in Table 4 suggest that I. hospitalis shuttles energy-producing metabolic precursors to N. equitans, as evidenced by enrichment sets related to increased levels of enzymes involved in energy production pathways specific to the I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture growth conditions. Reduction in the diversity of enriched cellular processes when comparing the profiles of the I. hospitalis-only cultures and the I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-cultures (Figures 1 and 2) corroborates a previous hypothesis that metabolic diversity is reduced in I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture samples due to I. hospitalis’s need to redirect its metabolism toward energy-producing metabolic pathways to sustain the growth of N. equitans [15]. In addition to this functional adaptation, identification of specific network connections involving ribosomal proteins, enzymes engaged in amino acid and NADH metabolism, and carbon flow through the I. hospitalis dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle has generated new insights about specific molecular processes mediating I. hospitalis-N. equitans inter-species interactions (summarized in Figure 5).

The omics datasets used in this study originate from growth conditions that were not identical; therefore, comparison of the reported transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics profiles from the original publications must be scrutinized. The variation in sampling time-points is a direct result of the high degree of difficulty in culturing N. equitans, which only grows in the presence of I. hospitalis. Nevertheless, proteomics analyses resulting from I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-cultures samples at different growth stages of I. hospitalis have failed to detect significant differences in protein profiles [15,19]. The interaction network connections presented here are based on the comparisons performed between matching conditions, however, it is likely that the different state of the cultures at the time of sampling contributed to an under-representation of physiological changes.

The distinctive difference in ribosomal protein clusters between the two culture types (Figure 3, Table 1) suggests that I. hospitalis may switch to an alternative set of ribosomal proteins in response to the physiological load imposed by its interactions with N. equitans. A comparable stress coping mechanism has been shown to occur in Mycobacterium tuberculosis [32]. In this case, the organism utilizes an alternate set of ribosomal proteins as a function of the availability of zinc [32]. Other types of ribosomal protein tuning have been documented, whereby cells make adjustments to the levels, ratios, or types of ribosomal proteins in order to facilitate optimal growth as a function of changing nutrient availability [29–31]. For I. hospitalis, these ribosomal proteins may reflect an adaptation to N. equitans attachment. Several different factors may be driving the tuning of ribosomal protein levels in the I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture samples. First, change in ribosomal protein composition could be employed by I. hospitalis to minimize the metabolic burden imposed on its growth in the presence of N. equitans. Mechanistically, this could result in selective translations of mRNA transcripts into subsets of proteins needed for I. hospitalis’ s own maintenance and survival, while simultaneously coping for the diversion of I. hospitalis metabolic resources toward the metabolic needs of N. equitans. Such a response would represent an energy-cost minimization strategy toward protein synthesis, which could compensate for a potential energy drain resulting from I. hospitalis’s co-existence with N. equitans [34]. Additionally, it is possible that in the presence of N. equitans, these ribosomal proteins are involved in moonlighting functions (i.e. they perform more than one cellular functions), and thus would need to be present in higher abundance [35,36]. Distinct changes observed in ribosomal protein composition suggest the presence of important alternative cellular mechanisms that may enable I. hospitalis to optimize its cellular requirements in light of N. equitans’s metabolic requirements.

The multi-level omics analysis also highlights the importance of selecting different amino acid pathways when I. hospitalis is grown by itself compared to when it is cultured in the presence of N. equitans (Table 2). This difference is particularly noteworthy as it has been shown that in co-culture with N. equitans, the amount of protein produced by I. hospitalis does not significantly increase or decrease compared to when I. hospitalis is grown without N. equitans [15]. It is thus thought that N. equitans’s survival depends on I. hospitalis to supply metabolites and energy-generating precursors as a mechanism to compensate for N. equitans’s very small genome and lack of metabolic enzyme-encoding genes, but may not necessarily require the physical transfer of amino acids between the two species [16,19]. The results of our system-level analysis support this hypothesis and provide insights into which metabolic precursors could be transferred to N. equitans upon co-culture growth with I. hospitalis.

It has also been shown that the protein expression profiles of N. equitans, when grown in co-culture with I. hospitalis, reflect enhanced levels of aromatic, hydrophobic, and positively-charged amino acids [37]. Of these amino acids, our analysis reveals protein enrichments corresponding to metabolic pathways involving phenylalanine, leucine, and isoleucine. Additionally, enzymes catalyzing the conversion of precursors to their respective amino acids are annotated in N. equitans for phenylalanine, leucine, and isoleucine [13]. Together these findings suggest that I. hospitalis shuttles specific amino acid precursors to N. equitans, as these cannot be independently synthesized by N. equitans.

Investigation into NADH metabolism clusters (Figure 4) also reveals interesting differences between the two I. hospitalis growth environments. The only components that are shared between the two types of cell cultures are two subunits of a NADH dehydrogenase encoded by genes located within the same locus and which are thought to be part of the same transcriptional unit that comprises other NADH dehydrogenase elements [12] (Figure 4, Supplementary Figure 2). Proteins encoded by all but one of these genes were found in I. hospitalis–only culture, whereas the I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture cluster contains just the two shared genes mentioned above. Additionally, the clusters differ in that they have other NADH metabolism gene components located in a separate gene cassette (Figure 4, Supplementary Figure 3). Surprisingly, the co-culture cluster has roughly half of the components, while the I. hospitalis-only cluster contains the other half of the components encoded by this gene cassette. This observation suggests that instead of entirely switching to an alternate set of NADH metabolic components, a rerouting of NADH oxidation pathways may render I. hospitalis better suited to adapt to the energetic coupling with N. equitans when grown as a co-culture (see summary Figure 5). Such a process could be controlled at the gene expression level by utilization of different promoters within these gene loci that are acted upon by different transcription factors. In this scenario, increased energy transfer could arise via coupling of I. hospitalis’s electron transport chain to ATP production in N. equitans. Analysis of the N. equitans genome reveals the most likely candidate for this ATP production machinery to be a putative sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase [12]. While the use of NADH as a substrate for this oxidoreductase remains to be confirmed, a shift to using an enzyme from N. equitans could rationalize why I. hospitalis decreases its production of NADH redox protein subunits when grown in co-culture with N. equitans.

Lower levels of protein components associated with the dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate carbon assimilation cycle as observed in the I. hospitalis-N. equitans network map suggest that elements of the CO2 carbon fixation pathways are altered, diverted, or slowed when I. hospitalis is grown in co-culture with N. equitans (Table 3). Previous work has revealed that when grown with N. equitans, I. hospitalis does not actively replicate [14]. This observation strongly suggests that cellular materials and metabolic energy normally used to increase the cellular biomass of I. hospitalis is diverted to meet the metabolic needs of N. equitans. None of the proteins annotated in the N. equitans genome are believed to function in a dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate carbon assimilation cycle [12]. Lower abundance of CO2 fixation enzymes in the STRING interaction maps of the I. hospitalis-N. equitans co-culture samples is consistent with previous observations suggesting that N. equitans acts as a parasite, consuming metabolites produced by I. hospitalis [16]. This metabolic shift away from carbon assimilation suggests an alternate mechanism by which I. hospitalis adapts its growth patterns and metabolic responses to the presence of N. equitans. Previous analysis using proteomics-only data indicated higher protein abundance levels for carbon fixation enzymes. Our multi-level analysis provides a more complex view of the cellular changes occurring in I. hospitalis when grown in co-culture with N. equitans.

Conclusion

Multi-level omics studies used to probe the biochemistry of complex organisms have been shown to strengthen our understanding of complex biological systems, and have provided insights into critical cellular mechanisms mediating interspecies interactions. Using an analysis of multi ‘omics’ datasets acquired independently, we have gained a deeper understanding of how the two archaeal organisms I. hospitalis and N. equitans interact with each other. This study clarifies previously described cellular networks and highlights cellular patterns that were not discernible previously from single transcriptomics, proteomics, or metabolomics analyses.

Results from this study suggest the presence of alternative pathways of ribosomal protein production and utilization, amino acid metabolism, and metabolic energy production, which together, point to possible adaptive mechanisms employed by I. hospitalis in response to N. equitans cells’ attachment, and concomitant growth of the two organisms. Such adaptive mechanisms appear to involve molecular switches that utilize less energy-demanding enzymes and cellular pathways. Findings from this study also provide evidence that metabolic precursors synthesized by I. hospitalis are shuttled to N. equitans to meet its cellular needs. This system-wide analysis applies statistical and visualization techniques to a multi-omics dataset to yield additional insights into the cellular activity of a complex biological system that was not readily discernable from independent single ‘omics’ analyses.

Supplementary Material

General Significance.

Our study applies statistical and visualization techniques to a mixed-source omics data set to yield a more global insight into a complex system, that was not readily discernable from separate omics studies.

Highlights.

Multi-omics analysis facilitates insight into archaeal interspecies interaction.

Metabolic reorganization focuses on amino acids and energy production.

Alternative ribosomal protein production and utilization employed during stress.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research (DE-SC0006654). The mass spectrometry facility at MSU receives funding from the Murdock Charitable Trust and NIGMS NIH P20GM103474 of the IDEA program. BB and RR receive funding from the National Science Foundation (MCB 1413321) that helped to develop methods used. The NMR metabolomics studies have been conducted at MSU’s NMR Center, which has received support from the NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant Program (1S10-RR026659-01), the NSF Major Research Instrumentation Grant program (NSF-MRI DBI-1532078), the Murdock Charitable Trust Foundation (Grant # 2015066:MNL:11/19/2015), and MSU’s Vice President for Research Office. The authors thank Dr. Harald Huber (University of Regensburg, Germany) for providing a bioreactor sample of I. hospitalis-N. equitans used for initial methods development.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aviner R, Shenoy A, Elroy-Stein O, Geiger T. Uncovering hidden layers of cell cycle regulation through integrative multi-omic analysis. PLOS Genet. 2015;11:e1005554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim S, Herazo-maya JD, Kang DD, Juan-guardela BM, Tedrow J, Martinez FJ, Sciurba FC, Tseng GC, Kaminski N. Integrative phenotyping framework ( iPF ): integrative clustering of multiple omics data identifies novel lung disease subphenotypes. BMC Genomics. 2015:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2170-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bordbar A, Mo ML, Nakayasu ES, Schrimpe-Rutledge AC, Kim YM, Metz TO, Jones MB, Frank BC, Smith RD, Peterson SN, Hyduke DR, Adkins JN, Palsson BO. Model-driven multi-omic data analysis elucidates metabolic immunomodulators of macrophage activation. Mol Syst Biol. 2012;8:558. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu Z, Zhang S, Liu H, Shen H, Lin X, Yang F, Zhou YJ, Jin G, Ye M, Zou H, Zhao ZK. A multi-omic map of the lipid-producing yeast Rhodosporidium toruloides. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1112. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell CJ, Getnet D, Kim MS, Manda SS, Kumar P, Huang TC, Pinto SM, Nirujogi RS, Iwasaki M, Shaw PG, Wu X, Zhong J, Chaerkady R, Marimuthu A, Muthusamy B, Sahasrabuddhe NA, Raju R, Bowman C, Danilova L, Cutler J, Kelkar DS, Drake CG, Prasad TSK, Marchionni L, Murakami PN, Scott AF, Shi L, Thierry-Mieg J, Thierry-Mieg D, Irizarry R, Cope L, Ishihama Y, Wang C, Gowda H, Pandey A. A multi-omic analysis of human naïve CD4+ T cells. BMC Syst Biol. 2015;9:75. doi: 10.1186/s12918-015-0225-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hultman J, Waldrop MP, Mackelprang R, David MM, McFarland J, Blazewicz SJ, Harden J, Turetsky MR, McGuire AD, Shah MB, VerBerkmoes NC, Lee LH, Mavrommatis K, Jansson JK. Multi-omics of permafrost, active layer and thermokarst bog soil microbiomes. Nature. 2015;521:208–212. doi: 10.1038/nature14238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muller EEL, Pinel N, Laczny CC, Hoopmann MR, Narayanasamy S, Lebrun LA, Roume H, Lin J, May P, Hicks ND, Heintz-Buschart A, Wampach L, Liu CM, Price LB, Gillece JD, Guignard C, Schupp JM, Vlassis N, Baliga NS, Moritz RL, Keim PS, Wilmes P. Community-integrated omics links dominance of a microbial generalist to fine-tuned resource usage. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5603. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang C, Yin A, Li H, Wang R, Wu G, Shen J, Zhang M, Wang L, Hou Y, Ouyang H, Zhang Y, Zheng Y, Wang J, Lv X, Wang Y, Zhang F, Zeng B, Li W, Yan F, Zhao Y, Pang X, Zhang X, Fu H, Chen F, Zhao N, Hamaker BR, Bridgewater LC, Weinkove D, Clement K, Dore J, Holmes E, Xiao H, Zhao G, Yang S, Bork P, Nicholson JK, Wei H, Tang H, Zhang X, Zhao L. Dietary modulation of gut microbiota contributes to alleviation of both genetic and simple obesity in children. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:966–982. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perez-Cobas AE, Gosalbes MJ, Friedrichs A, Knecht H, Artacho A, Eismann K, Otto W, Rojo D, Bargiela R, von Bergen M, Neulinger SC, Daumer C, Heinsen F-A, Latorre A, Barbas C, Seifert J, dos Santos VM, Ott SJ, Ferrer M, Moya A. Gut microbiota disturbance during antibiotic therapy: a multi-omic approach. Gut. 2013;62:1591–1601. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paper W, Jahn U, Hohn MJ, Kronner M, Näther DJ, Burghardt T, Rachel R, Stetter KO, Huber H. Ignicoccus hospitalis sp. nov., the host of “Nanoarchaeum equitans”. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:803–8. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64721-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huber H, Hohn MJ, Rachel R, Fuchs T. A new phylum of Archaea represented by a nanosized hyperthermophilic symbiont. Nature. 2002;417:63–67. doi: 10.1038/417063a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Podar M, Anderson I, Makarova KS, Elkins JG, Ivanova N, Wall Ma, Lykidis A, Mavromatis K, Sun H, Hudson ME, Chen W, Deciu C, Hutchison D, Eads JR, Anderson A, Fernandes F, Szeto E, Lapidus A, Kyrpides NC, Saier MH, Richardson PM, Rachel R, Huber H, Eisen Ja, Koonin EV, Keller M, Stetter KO. A genomic analysis of the archaeal system. Ignicoccus hospitalis-Nanoarchaeum equitans. 2008 doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-11-r158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waters E, Hohn MJ, Ahel I, Graham DE, Adams MD, Barnstead M, Beeson KY, Bibbs L, Bolanos R, Keller M, Kretz K, Lin X, Mathur E, Ni J, Podar M, Richardson T, Sutton GG, Simon M, Soll D, Stetter KO, Short JM, Noordewier M. The genome of Nanoarchaeum equitans: insights into early archaeal evolution and derived parasitism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12984–12988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1735403100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jahn U, Gallenberger M, Paper W, Junglas B, Eisenreich W, Stetter KO, Rachel R, Huber H. Nanoarchaeum equitans and Ignicoccus hospitalis: new insights into a unique, intimate association of two archaea. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1743–50. doi: 10.1128/JB.01731-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giannone RJ, Huber H, Karpinets T, Heimerl T, Küper U, Rachel R, Keller M, Hettich RL, Podar M. Proteomic characterization of cellular and molecular processes that enable the Nanoarchaeum equitans--Ignicoccus hospitalis relationship. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamerly T, Tripet BP, Tigges M, Giannone RJ, Wurch L, Hettich RL, Podar M, Copié V, Bothner B. Untargeted metabolomics studies employing NMR and LC–MS reveal metabolic coupling between Nanoarcheum equitans and its archaeal host Ignicoccus hospitalis. Metabolomics. 2014;11:895–907. doi: 10.1007/s11306-014-0747-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huber H, Kuper U, Daxer S, Rachel R. The unusual cell biology of the hyperthermophilic crenarchaeon Ignicoccus hospitalis, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. Int J Gen Mol Microbiol. 2012;102:203–219. doi: 10.1007/s10482-012-9748-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wurch L, Giannone RJ, Belisle BS, Swift C, Utturkar S, Hettich RL, Reysenbach AL, Podar M. Genomics-informed isolation and characterization of a symbiotic Nanoarchaeota system from a terrestrial geothermal environment. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12115. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giannone RJ, Wurch LL, Heimerl T, Martin S, Yang Z, Huber H, Rachel R, Hettich RL, Podar M. Life on the edge: functional genomic response of Ignicoccus hospitalis to the presence of Nanoarchaeum equitans. ISME J. 2014;9:101–14. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki Ra. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Minguez P, Doerks T, Stark M, Muller J, Bork P, Jensen LJ, Mering Cv. The STRING database in 2011: functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D561–D568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhate A, Parker DJ, Bebee TW, Ahn J, Arif W, Rashan EH, Chorghade S, Chau A, Lee JH, Anakk S, Carstens RP, Xiao X, Kalsotra A. ESRP2 controls an adult splicing programme in hepatocytes to support postnatal liver maturation. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8768. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaniewska P, Chan CKK, Kline D, Ling EYS, Rosic N, Edwards D, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Dove S. Transcriptomic changes in coral holobionts provide insights into physiological challenges of future climate and ocean change. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White RR, Milholland B, MacRae SL, Lin M, Zheng D, Vijg J. Comprehensive transcriptional landscape of aging mouse liver. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:899. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2061-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franceschini A, Szklarczyk D, Frankild S, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Lin J, Minguez P, Bork P, von Mering C, Jensen LJ. STRING v9.1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D808–D815. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabb DL, Fernando CG, Chambers MC. MyriMatch: highly accurate tandem mass spectral peptide identificaiton by multivariate hypergeometric analysis. J Proteome Res. 2008;6:654–661. doi: 10.1021/pr0604054.MyriMatch. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang DW, Lempicki RA, Sherman BT. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karp PD, Ouzounis CA, Moore-kochlacs C, Goldovsky L, Tsoka S, Darzentas N, Kunin V, Kaipa P, Ahre D. Expansion of the BioCyc collection of pathway / genome databases to 160 genomes. 2005;33:6083–6089. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asato Y. Control of ribosome synthesis during the cell division cycles of E. coli and Synechococcus. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2005;7:109–17. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15580783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosdriesz E, Molenaar D, Teusink B, Bruggeman FJ. How fast-growing bacteria robustly tune their ribosome concentration to approximate growth-rate maximization. FEBS J. 2015;282:n/a-n/a. doi: 10.1111/febs.13258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordiyenko Y, Videler H, Zhou M, McKay AR, Fucini P, Biegel E, Müller V, Robinson CV. Mass spectrometry defines the stoichiometry of ribosomal stalk complexes across the phylogenetic tree. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:1774–1783. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M000072-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prisic S, Hwang H, Dow A, Barnaby O, Pan TS, Lonzanida JA, Chazin WJ, Steen H, Husson RN. Zinc regulates a switch between primary and alternative S18 ribosomal proteins in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 2015;97:263–280. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huber H, Gallenberger M, Jahn U, Eylert E, Berg Ia, Kockelkorn D, Eisenreich W, Fuchs G. A dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate autotrophic carbon assimilation cycle in the hyperthermophilic Archaeum Ignicoccus hospitalis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7851–7856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801043105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Folsom JP, Parker AE, Carlson RP. Physiological and proteomic analysis of Escherichia coli iron-limited chemostat growth. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:2748–2761. doi: 10.1128/JB.01606-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Copley SD. Moonlighting is mainstream: Paradigm adjustment required. BioEssays. 2012;34:578–588. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luo X, Hsiao HH, Bubunenko M, Weber G, Court DL, Gottesman ME, Urlaub H, Wahl MC. Structural and functional analysis of the E. coli NusB-S10 transcription antitermination complex. Mol Cell. 2008;32:791–802. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das S, Paul S, Bag SK, Dutta C. Analysis of Nanoarchaeum equitans genome and proteome composition: indications for hyperthermophilic and parasitic adaptation. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:186. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.