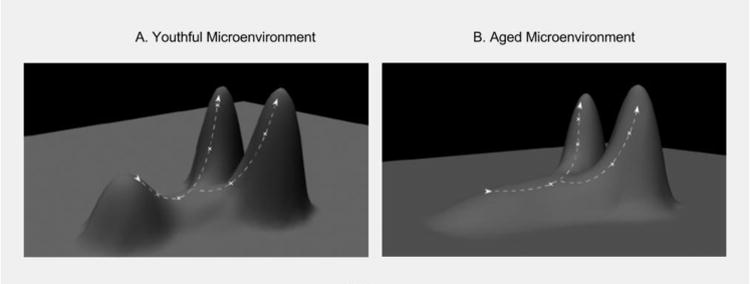

Figure 2. Changing Landscapes in Oncogenesis.

A) In a young and healthy stem cell niche, stem and progenitor cells are well adapted to their environments. On a fitness landscape, this state can be conceptualized as a local fitness peak (short peak). The x-y plane reflects all possible genotypes, and thus different cellular phenotypes change. Phenotypic change results in movement on the fitness landscape. When near the apex of a fitness peak, mutations that result in a phenotypic change will likely be disadvantageous, resulting in downhill movement on the landscape. Because this mutant cell is now less adapted to its environment than its peers, it will likely be eliminated from the gene pool by competition from cellular peers. This elimination will make it improbable for the cell clone to acquire a subsequent oncogenic mutation. Because youthful environments experience strong purifying selection, most phenotypic changes will be detrimental to a cell's survival. B) In an aged individual, stem and progenitor cells are less adapted to their age-altered tissue microenvironment, thus lowering the overall fitness peak of the pool. With this lowered fitness peak purifying selection is relaxed, allowing for the survival of different stem cell phenotypes. This altered fitness landscape increases the probability that a stem cell can achieve a higher position (greater fitness) on the landscape through a single mutational step. Subsequent oncogenic mutations may then allow the original cell clone to ‘climb’ to higher fitness positions, in some cases generating more aggressive cancerous phenotypes.