The US health care system is in a time of unprecedented change. The expansion of insurance coverage, redesign of the reimbursement systems, and growing influence of patient-centered medical homes and accountable care organizations all bring opportunities for those interested in the prevention of disease, injury, and premature death for entire communities as well as individual patients.1,2 It is, in short, a time when public health can come to the fore.

Public health practitioners can assist clinical providers in assuring that newly insured people receive services that promote health and do not simply treat illness. They can help insurers identify the quality measures and incentives that yield better health outcomes and control costs. They can provide evidence of effective interventions that were previously funded by public health grants but can now be brought to scale if paid for by the health care sector. And they can even point to ways to complement traditional health care treatment with community-oriented population health measures.

It is obvious that none of this will come easily. Nonetheless, at this moment—unprecedented in the careers of most public health practitioners, and of uncertain duration—it is critically important to try.

Public health practitioners need to be on the lookout for the circumstances in which their expertise may be of value—such as those created by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation’s State Innovation Model grants or its Accountable Health Communities initiative. Once the potential opportunities are identified, the next step is to get to the table where the discussions occur. But even more important, once public health practitioners get a seat, they must be prepared to make a positive contribution. That requires familiarity with and sensitivity to the needs, concerns, and goals of clinical providers and the insurance industry—and readiness to offer concrete and specific suggestions that fit the occasion. Awareness of all these factors, however, is complicated by the multiple interpretations of prevention (primary, secondary, tertiary) and varying definitions of population health (a patient panel, a payer’s covered lives, a total community).3

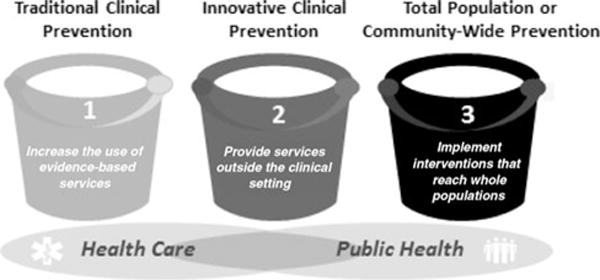

Rather than choosing between one approach and another, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed a conceptual population health and prevention framework with 3 categories—or as we have come to call them, “buckets”—of prevention (Figure). Each one will be needed to yield the most promising results for a population, regardless of whether the population is defined narrowly, as, for example, the patients in a medical practice, or broadly, as, for example, the residents of a state. This 3-part framework may be particularly useful as a way of maximizing the likelihood that clinicians, insurers, and public health practitioners attend to traditional office-based as well as innovative clinical approaches and do not neglect the community factors that have an enormous impact on health.

FIGURE.

Three Buckets of Prevention

What Are These 3 Buckets?

Traditional clinical preventive interventions

These approaches involve the care provided by physicians and nurses in a doctor’s office during a routine one-to-one encounter. They have a strong evidence base for efficacy in health improvement and/or cost-effectiveness. Examples include seasonal flu vaccines, colonoscopies, and screening for obesity and tobacco use. While such traditional clinical preventive interventions have historically been reimbursed by insurers, and many are now even mandated for most plans by the Affordable Care Act without cost sharing, there is often room for improvement in their promotion and rate of adoption. Improvement can be achieved by various action steps by insurers (eg, increasing the weight with which various preventive interventions are financially incentivized as quality measures), by clinical practices (eg, carefully monitoring that each clinician in the practice provides them), and by public health practitioners (eg, designing social marketing aimed at the public and/or clinical providers and promoting best practices).4,5

A new effort that focuses on the patient-oriented buckets—the first 2 in this list—is the CDC’s 6|18 Initiative, which is designed to promote the adoption of evidence-based interventions by health care purchasers and payers (www.cdc.gov/sixeighteen). The name comes from the initial focus on 6 high-burden health conditions and 18 evidence-based interventions that can improve health and/or save money in a relatively short time period. The CDC has tapped subject matter expertise within the agency and culled public health and clinical research to pinpoint those clinical preventive approaches that offer some of the clearest and strongest evidence of effectiveness. For example, the 6|18 Initiative proposes the elimination of cost sharing for medications to treat hypertension and cholesterol and for tobacco cessation drugs, since, as research points out, even low co-pay charges for such drugs discourage many patients from taking them.6–9 It also high-lights the benefits of comprehensive reproductive care by including information about long-acting reversible contraception, which has proven to be highly effective in preventing unintended pregnancies.10–12

Innovative preventive interventions that extend care outside the clinical setting

The approaches in bucket 2 are, like the approaches in bucket 1, clinical in nature and patient-focused. But they include interventions that have not been historically paid for by fee-for-service insurance and occur outside of a doctor’s office setting—interventions that have nonetheless been proven to work in a relatively short time.13 Several have been piloted within the public health sector with grants from governmental agencies and foundations.

An example of a bucket 2 approach grew out of epidemiologic analysis by the Camden Coalition of Health Providers in New Jersey. By geocoding Camden health data, Camden Coalition staff identified a disproportionate number of symptomatic asthmatic patients living in 2 buildings. In response, they designed home-based approaches to identify and reduce environmental triggers and provide customized, home-based preventive educational counseling.14–16

The 6|18 Initiative has identified a number of the interventions in this bucket as well. For example, it has summarized the evidence for the use of community health workers to provide Camden-like home-based education and trigger remediation for the families of children with moderate to severe asthma.17–20 In addition, it highlights the benefits of the use of the well-established CDC National Diabetes Prevention Program and its multisession, community-based, behavioral change interventions to prevent or reduce the symptoms associated with diabetes.21–23 Both of these are examples of extending care for individuals from the clinical setting to the community.

Total population or community-wide interventions

With bucket 3, the focus shifts. It includes interventions that are no longer oriented to a single patient or all of the patients within a practice or even all patients covered by a certain insurer. Rather, the target is an entire population or subpopulation usually identified by a geographic area. Interventions are based not in the doctor’s office but in such settings as a neighborhood, city, county or state.3 This bucket is the one that is most unfamiliar to the clinical sector but quite comfortable to the public health sector.

While public health has significant experience with such total population approaches, not all of them have a proven and strong evidence base. Interventions may be associated with, say, promoting a healthy behavior or preventing an unhealthy one—although research to confirm the impact may not have been conducted. In some total population interventions, the impact is shown to occur over the course of many years or even a generation. Such interventions may be a lower priority to insurers and stakeholders who are focused on a short-term return on investment. The longstanding Guide to Community Preventive Services (Community Guide) offers clear direction on which approaches have the strongest track records.

Nonetheless, some total population interventions do have a strong evidence base regarding improved health and/or cost within a relatively short time. For example, cigarette taxes, smoking ban regulations or laws, and well-designed advertising campaigns have each been shown to have a rapid impact on reduced cigarette use.24 And a reduction in cigarette use has been associated with a statistically significant decline in serious health consequences within 18 months.25 There is also evidence that community-wide, multifactorial, coordinated efforts to promote healthful eating and increased physical activity have resulted in a decline in the childhood risk for obesity within a few years.26 Similarly, housing policies that reduce environmental triggers have been shown to reduce active asthma symptoms and health services utilization within a few years.20,27

Clearly, pilots are needed to prove the feasibility of financial incentives for clinicians for the promotion of total population health interventions. Some initial efforts are under way to link global payments to improvement in specific health indicators in community populations.3 States such as Vermont and Oregon are considering total population health measures in their delivery system reform plans. The larger the market share of a clinical provider, the more likely that a community-wide intervention will be seen as being in its financial interest.

In addition to its 6|18 Initiative, CDC has also created the Community Health Improvement Navigator Web site (www.cdc.gov/CHInav), with information and resources that illustrate how the clinical sector can support evidence-based approaches with the targeted and strategic use of community benefits by nonprofit hospitals. Other tools in development will summarize the evidence for total population intervention.

Coordinated multisector initiatives that promote all 3 buckets simultaneously may result in the largest gains. One example of this occurred in Massachusetts after it implemented its health care reform initiative in 2007. The state expanded its cost-free insurance Medicaid coverage for tobacco cessation medications, linked patients to counselors on a Quitline, and promoted the increased accessibility and overall benefit of tobacco cessation interventions in public information campaigns. When work in each bucket was focused on a single goal, smoking rates plummeted.28–30

Summary

In summary, this is a critical moment in health system transformation in America. Change of this magnitude may not occur again in our lifetimes. Full participation of public health practitioners in the process will help achieve the goal of ensuring access to high-quality and effective clinical preventive services, both traditional and innovative, while at the same time working upstream to promote health and wellness in community settings. Public health practitioners should have at their fingertips specific, evidence-based, prevention-related proposals that fit multiple settings—from the doctor’s office to the insurer’s conference room to the neighborhood meeting to the state house.2

An optimal strategy is one in which prevention approaches span the 3 buckets—traditional and innovative clinical preventive as well as total population interventions.2,31,32 Each bucket requires its own prioritized interventions and funding sources.13 At some “tables” and in some settings, only 1 of the 3 buckets may be of interest to the participants. Public health professionals add value when they stand ready to adapt their proposals to fit the opportunity at hand. But ultimately, a holistic preventive strategy requires a focus on all 3 buckets delivered in a thoughtful and coordinated manner—taking advantage of the greatly expanded possibilities that stand before the public health community.2,5,13

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Koh H, Tavenner M. Connecting care through the clinic and community for a healthier America. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(suppl 3):S305–S307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300760.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halfon N, Long P, Chang D, Hester J, Inkelas M, Rodgers A. Applying A 3.0 transformation framework to guide large-scale health system reform. Health Aff. 2014;33(11):2003–2011. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0485.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hacker K, Walker D. Achieving population health in accountable care organizations. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1163–1167. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301254.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kindig D, McGinnis J. Determinants of U.S. Population Health: Translating Research Into Future Policies. [Report] Altarum Policy Roundtable. Washington, DC: Altarum; 2007. http://altarum.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-publication-files/07_28Nov_Roundtable_Determinants_of_Health-RTR.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auerbach J, Chang D, Hester J, Magnan S. Opportunity Knocks: Population Health in State Innovation Models [Discussion Paper.] Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2013. http://www.iom.edu/Global/Perspectives/2013/OpportunityKnocks. Accessed November 1, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Guide to Community Preventive Services. Cardiovascular disease prevention and control: reducing out-of-pocket costs for cardiovascular disease preventive services for patients with high blood pressure and high cholesterol. www.thecommunityguide.org/cvd/ROPC.html. Updated June 30, 2015. Accessed November 1, 2015.

- 7.Choudhry N, Bykov K, Shrank WH, et al. Eliminating medication copayments reduces disparities in cardiovascular care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(5):863–870. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0654.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joyce GF, Niaura R, Maglione M, et al. The effectiveness of covering smoking cessation services for Medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(6):2106–2123. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00891.x.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Community Guide. Reducing tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure: reducing out-of-pocket costs for evidence-based cessation treatments [online] http://www.thecommunityguide.org/tobacco/outofpocketcosts.html. Published 2012. Accessed November 1, 2015.

- 10.Trussell J, Henry N, Hassan F, Prezioso A, Law A, Filonenko A. Burden of unintended pregnancy in the United States: potential savings with increased use of long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2013;87(2):154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.07.016.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rickets S, Klingler G, Schwalberg R. Game change in Colorado: widespread use of long-acting reversible contraceptives and rapid decline in births among young, low-income women. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;46(3):125–132. doi: 10.1363/46e1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez MI, Evans M, Espey E. Advocating for immediate postpartum LARC: increasing access, improving outcomes, and decreasing cost. Contraception. 2014;90(5):468–471. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hester J, Stange P, Seeff L, Davis J, Craft C. Toward Sustainable Improvements in Population Health: Overview of Community Integration Structures and Emerging Innovations in Financing. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2015. (CDC Health Policy Series, No. 2). http://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/27844. Accessed November 1, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers. Blog post. http://www.camdenhealth.org/finding-medical-hotspots-helps-cut-cost/. Accessed November 1, 2015.

- 15.Gawande A. The hot spotters: can we lower medical costs by giving the neediest patients better care? The New Yorker. 2011 Jan;:41–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weech-Maldonado R, Merrill S. Building partners with the community: lessons from the Camden Health Improvement Learning Collaborative. J Healthc Manage. 2000 http://www.biomedsearch.com/article/Building-Partnerships-with-Community-Lessons/62297470.html. Accessed November 1, 2015. [PubMed]

- 17.Clark N, Feldman CH, Evans D, Levison M, Wasilewski Y, Mellins R. The impact of health education on frequency and cost of health care use by low income children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1986;78(1, pt 1):108–115. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(86)90122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karnick P, Margellos-Anast H, Seals G, Whitman S, Aliadeff G, Johnson D. The pediatric asthma intervention: a comprehensive cost-effective approach to asthma management in a disadvantaged inner-city community. J Asthma. 2007;44(1):39–44. doi: 10.1080/02770900601125391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell JD, et al. Community health worker home visits for Medicaid-enrolled children with asthma: effects on asthma outcomes and costs. Am J Public Health. 2015:e1–e7A. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bryant-Stephens T, Kurian C, Guo R, Zhao H. Impact of a household environmental intervention delivered by lay health workers on asthma symptom control in urban, disadvantaged children with asthma. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(suppl 3):S657–S665. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.165423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Community Guide. Diabetes prevention and control: combined diet and physical activity promotion programs to prevent type 2 diabetes among people at increased risk [online] http://www.thecommunityguide.org/diabetes/combineddietandpa.html. Published 2014. Accessed November 1, 2015.

- 22.Ali MK, Echouffo-Tcheugui J, Williamson DF. How were lifestyle effective were lifestyle intervention in real-world settings real-world settings that were modeled on the diabetes prevention diabetes prevention program? Database of Abstracts of Reviews of EFFECTS (DARE): Quality-assessed Reviews [online] 2012 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1009. Accessed November 1, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vojta D, Koehler TB, Longjohn M, Lever JA, Caputo NF. A coordinated national model for diabetes prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(suppl 4):S301–S306. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. Accessed November 1, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2010. Accessed November 1, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Economos C, Hyatt R, Goldberg J, et al. A Community intervention reduces BMI z-score in children: shape up Somerville first year results. Obesity. 2007;15:1325–1336. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nurmagambetov TA, Barnett SBL, Jacob V, et al. Economic value of home-based, multi-trigger, multicomponent interventions with an environmental focus for reducing asthma morbidity: a community guide systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2S1):S33–S47. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warner D, Land T, Rodgers A, Keithly L. Integrating tobacco cessation quitlines into health care: Massachusetts, 2002–2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E133. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110343. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd9.110343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Land T, Warner D, Paskowsky M, et al. Medicaid coverage for tobacco dependence treatments in Massachusetts and associated decreases in smoking prevalence. Plos One. 2010;5(3):e9770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richard P, West K, Ku L. The return on investment of a Medicaid tobacco cessation program in Massachusetts. PloS One. 2012;7(1):e29665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):590–595. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Prevention Council. National Prevention Strategy. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2011. [Google Scholar]