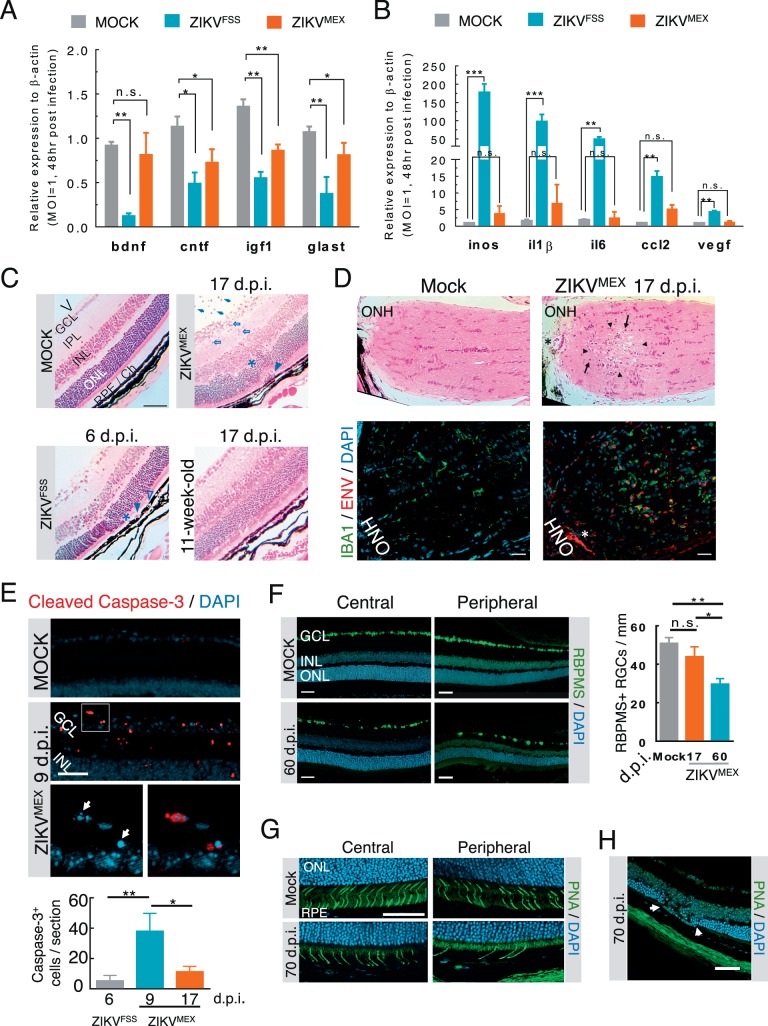

Figure 5.

Functional consequences of ZIKV infection of the retina. (A, B) Quantitative RT-PCR analyses of neurotrophic and proinflammatory gene expression in cultured Müller cells infected with either ZIKVFSS or ZIKVMEX (n = 4). (C) H&E-stained retinal histology sections from infected A129 mice. The age of the animals was either 3 or 11 weeks at time of viral inoculation. V, vitreous cavity. Arrows: intravitreal infiltrates; open arrows: retinitis with cell infiltration; asterisks: outer nuclear layer damage; arrowheads: subretinal inflammatory cells; open arrowheads: RPE defects. (D) H&E-stained sections of the optic nerve head (ONH). Immediately neighboring sections were stained for viral ENV and IBA1+ cell infiltration. Arrowheads: necrotic lesion; arrows: mononuclear cell infiltrate; asterisk: same blood vessel on adjacent sections. (E) Representative micrograph of cleaved caspase-3 staining. The boxed area at the top was enlarged to show nuclear condensation and fragmentation (arrows). Caspase-3-positive cells were quantified on six slides from each animal (n = 4 each group). (F) Immunostaining of central and peripheral retinal ganglion cells from mock- or ZIKVMEX-infected mice at 60 dpi. Quantitative data were based on the average number of RBPMS-positive cells on 10 retinal sections (n = 3 each group). (G) Staining of cone cells by peanut agglutinin (PNA) at central and peripheral retina. (H) Focal photoreceptor degeneration. Scale bars: 100 μm (C, D); 50 μm (E–H). Data were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA with Turkey post hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001.