Abstract

Objective

To estimate the cost of smoking in Singapore in 2014 from the societal perspective.

Methods

A prevalence-based, disease-specific approach was undertaken to estimate the smoking-attributable costs. These include direct and indirect costs of inpatient treatment, premature mortality, loss of productivity due to medical leaves and smoking breaks.

Results

In 2014, the social cost of smoking in Singapore was conservatively estimated to be at least US$479.8 million, ∼0.2% of the 2014 gross domestic product. Most of this cost was attributable to productivity losses (US$464.9 million) and largely concentrated in the male population (US$434.9 million). Direct healthcare costs amounted to US$14.9 million where ischaemic heart disease and lung cancer had the highest cost burden.

Conclusions

The social cost of smoking is smaller in Singapore than in other Asian countries. However, there is still cause for concern. A recently observed increase in smoking prevalence, particularly among adolescent men, is likely to result in rising total cost. Most significantly, our results suggest that a large share of the overall cost burden lies outside the healthcare system or may not be highly salient to the relevant decision makers. This is partly because of the nature of such costs (indirect or intangible costs such as productivity losses are often not salient) or data limitations (a potentially significant fraction of direct healthcare expenditure may be in private primary care where costs are not systematically captured and reported). The case of Singapore thus illustrates that even in countries perceived as success stories, strong multisectoral anti-tobacco strategies and a supporting research agenda continue to be needed.

Keywords: Tobacco and smoking, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides a timely update to the cost of smoking in Singapore as the last publication was dated 2002.

The study also attempts to provide a more accurate reflection of the societal cost by including the cost of presenteeism and healthcare costs incurred in subsidised hospital wards.

However, the cost data reflected remain as an underestimate of the true cost due to a lack of data.

Introduction

There is robust evidence on the negative impact of tobacco smoking on individuals' health. Studies have shown that smoking directly causes or increases the risks of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases,1 2 various types of cancers3–5 and diabetes.6 Non-smokers are also subjected to heightened risks of these diseases due to secondhand smoke.7 8 From a global perspective, ∼6 million people die each year from smoking and another 600 000 deaths occurred due to the effects of secondhand smoke, higher than the death tolls from tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and malaria combined.9

Singapore has often been lauded for taking a tough stance on tobacco. Smoking prevalence is currently relatively low—14.3% in 2010 (24.7% for men, 4.2% for women),10 which may be attributed to its strong ongoing commitment to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), under which the government introduced a series of policies including underage smoking restrictions, warning labels, restricted advertising and high taxation. More recently, developments include a 10% hike in tobacco excise tax in 2014,11 the Health Promotion Board's ‘I Quit’ campaign,12 the banning of shisha in 201413 and the ban on electronic cigarettes and other emerging tobacco products in 2015.14

In 1997, prior to many of these concerted actions, Quah et al15 estimated that the social cost of smoking in Singapore ranged from US$530.4 million (SGD673.6 million) to US$660.6 million (SGD839.2 million). The objective of this paper is therefore to revisit the social cost of smoking after almost two decades of anti-tobacco policies in Singapore and to assess the implications of a recent resurgence in smoking prevalence in the light of this re-examination.

Methods

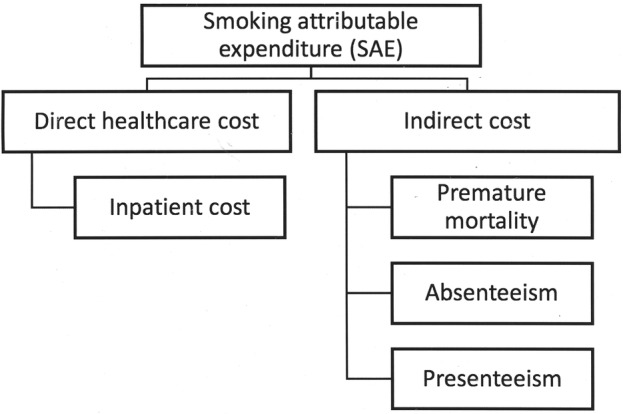

The impact of smoking on society is not just the medical cost. It also includes an indirect cost such as the loss of productivity from smoking-related diseases (figure 1). In this paper, we used a prevalence-based approach to measure the cost of smoking in a specific time period.16–18 The smoking attributable expenditure (SAE) estimated from the society's perspective consisted of direct inpatient medical costs and indirect costs due to loss of productivity from illness (absenteeism), smoking breaks (presenteeism) and the cost of premature mortality. The cost of premature mortality refers to the economic losses incurred by society when a person dies at a younger age than expected age due to smoking. Meanwhile, the loss of productivity was estimated by absenteeism—that is, when the person is not at work due to illnesses related to smoking or present at work (presenteeism) but has lower productivity.

Figure 1.

Cost conceptual framework.

Data sources

To evaluate the cost of smoking in Singapore, population smoking-attributable fractions (SAF) of various diseases were estimated based on a 2010 (unpublished) Singapore Comparative Risk Assessment Study conducted by the Singapore Ministry of Health (MOH). Gender-specific and age group-specific (5-year interval) estimated SAFs of mortality for 19 diseases in 2010 between ages 0 and 85 years and over were calculated. As in other regional studies with limited data (see, for instance, Taiwan19 and Vietnam20), these SAFs of mortality were used as best available proxies for SAF of overall disease burden. The overall SAF figures for each disease are listed in table 1. Disease-specific hospital bill size data were retrieved from the MOH website.21 Gender-specific and age group-specific (10-year interval) smoking prevalence was reported in the 2010 National Health Survey.10 Finally, data on 2014 gender-specific and age group-specific median incomes, labour participation rates and population figures were derived from the Ministry of Manpower (MOM)22 and the Department of Statistics Singapore. Given the nature of the data sources, this study was exempted from ethics review. The social cost of smoking was estimated for Singaporeans and permanent residents aged 20 years and above. All reported costs are in US dollars (where US$1=SG$1.27) for the year 2014.

Table 1.

Overall SAF by gender in 2010

| SAF (%)*† |

||

|---|---|---|

| Disease cause | Male | Female |

| Mouth cancer | 0.47 | 0.34 |

| Oesophagus cancer | 0.47 | 0.48 |

| Lung cancer | 0.87 | 0.71 |

| Larynx cancer | 0.69 | 0.66 |

| Pancreas cancer | 0.20 | 0.21 |

| Bladder cancer | 0.36 | 0.41 |

| Kidney cancer | 0.45 | 0.41 |

| Stomach cancer | 0.19 | 0.12 |

| Uterus cancer | N.A. | −0.24 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 0.16 | 0.02 |

| Stroke | 0.13 | 0.01 |

| COPD | 0.53 | 0.67 |

| Parkinson’s disease | −0.13 | −0.01 |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Low birth weight | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Fire injuries | 0.23 | 0 |

*The SAF figure takes into account passive smoking.

†SAF figures for three other diseases—otitis media, asthma and age-related macular degeneration—were provided. SAF for otitis media and asthma was 0 across all age groups in Singapore's context and there were no deaths due to age-related macular degeneration in Singapore, so the SAF for these two diseases were not included in the table.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases; SAF, smoking-attributable fraction.

Estimation of SAF

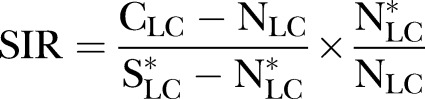

The calculation of the SAF followed the methodology of the Australian Burden of Disease Report 2003.23 Using this methodology, the SAF for mortality may not be directly estimated from current smoking prevalence due to the long lag time between smoking exposure and certain diseases, particularly cancers. For such diseases, ‘smoking impact ratio (SIR)’ was calculated. The age group-specific and gender-specific SIR was expressed as a comparison of the excess mortality due to lung cancer in Singapore, and the excess mortality due to lung cancer in a well-studied reference population, the American Cancer Society's Cancer Prevention Study II.

|

1 |

where CLC denotes the number of lung cancer deaths in current smokers in Singapore, NLC is the number of lung cancer deaths in non-smokers in Singapore,  is the number of lung cancer deaths in smokers in the reference population and

is the number of lung cancer deaths in smokers in the reference population and  denotes the number of lung cancer deaths in non-smokers in the reference population.

denotes the number of lung cancer deaths in non-smokers in the reference population.

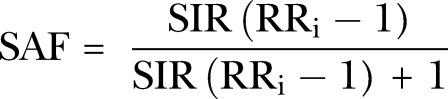

The SIR figure was subsequently used to replace smoking prevalence in the calculation of the SAF of mortality for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) and other types of cancers. For non-cancers, SAF for mortality was calculated using smoking prevalence rates.

|

2 |

where RRi denotes the disease-specific mortality risk ratio.

Medical cost

Direct medical cost was calculated based on four major diseases associated with smoking (lung cancer, ischaemic heart disease, stroke and COPD), for which data on hospital inpatient bill size for a sample of public and private hospitals were made publicly available by MOH. Data on outpatient bills and out-of-pocket expenditures were unfortunately not available.

In Singapore, ward class determines the total cost of care and the amount of subsidy patients get, from 0% in class A wards (with full amenities such as private rooms and air-conditioning) to almost 80% subsidy in class C wards (with more limited amenities and means-tested access).24 The publicly available data provide inpatient volume as well as the 50th and 90th centile cost for each disease by hospital and ward class.

Average hospital bill sizes between 1 Feb 2014 and 31 January 2015 were estimated by assuming that bill sizes followed a hospital and ward-class-specific lognormal distribution and solving for the mean disease-specific hospital bill size for each ward class in the respective hospitals given the reported percentile values. Given the societal perspective of the analysis, subsidies provided for lower class wards were then factored back into the calculation to recover estimated total actual healthcare costs.

In the absence of more specific demographic breakdowns, we also assumed the age-specific, gender-specific and disease-specific proportions of inpatient volume to be the same as the observed age-specific, gender-specific and disease-specific proportions of mortality. For example, in the case of lung cancer, ∼7.3% of the deaths were of men aged 60–64 years, and we therefore attributed 7.3% of the total inpatient volume to men aged 60–64 years.

The direct medical cost of smoking was then estimated based on the disease-specific average estimated cost (in each hospital and ward class) multiplied by patient volume, taking into account the SAF. Owing to a lack of data, healthcare costs from the primary health sector (ie, private general practitioners' clinics and polyclinics), the intermediate and long-term care sector (including nursing home and community hospitals), as well as the cost of other smoking-related diseases such as stomach and kidney neoplasms, were not included.

Indirect cost

On the basis of the human capital approach,25 the monetary value of lost productivity was assumed to be equal to the wage rate. The economic impact of absenteeism from work was calculated by multiplying the average age-specific and gender-specific daily wages by the average length of stay (LOS) for the four diseases stated above, accounting for SAF, age-specific and gender-specific inpatient volume proportions and labour participation rate.

Approximately 25% of the population aged 70–75 years and 10% of the population aged 75 and over reported working in 2015. However, the MOM reports age-specific salary rates only up to the category ‘60 and over’. Salary estimates for individuals above 70 are likely to be significantly lower or may need to account for part-time work, but cannot be reliably estimated from the existing data. As a result, to be conservative, unlike the calculation for direct healthcare cost, we include productivity costs only for individuals aged 69 and below. Total LOS was determined by multiplying the disease-specific inpatient volume for each hospital ward class with their respective average LOS. Overall average LOS for each disease was then determined by dividing the total LOS by the total volume.

To estimate the economic impact of premature deaths, in addition to a smoker's current salary, the value of his/her lost future productivity (proxied for by future salary up to age 69 years) was taken into account and discounted to derive the present value as of 2014. The present cost of forgone lifetime earnings (PVLE) was thus calculated as total smoking attributable deaths across the 19 diseases, multiplied by the labour participation rate and expected future earnings at a discount rate of 3%. The income growth rate was arbitrarily set at 2%, as the annualised change in real wages between 2009 and 2014 was 2%.26

Finally, the cost of smoking breaks was estimated based on the assumption that smokers only take one 10-min smoking break daily. We used this as the baseline scenario on the basis that this most likely represents a reasonable lower-bound estimate. Given that smoking breaks require long trips outside due to smoking area restrictions, this assumption is likely to be conservative. While there are no local published studies that formally substantiate this assumption, this was consistent with unpublished observational data gathered in other studies conducted by local principal investigators and also reflected the principle of conservatism. We then estimated productivity losses taking into consideration the size of the workforce, gender-specific and age group-specific smoking prevalence and wages. Table 2 describes the cost estimation formulas.

Table 2.

Cost estimation calculations

| Types of cost | Cost estimation |

|---|---|

| Direct cost | |

| Medical cost of hospitalisations | Death proportioniga * inpatient volumeiga * average healthcare costig * SAFiga |

| Indirect cost | |

| Loss of productivity | Death proportioniga * inpatient volumeiga * average LOSig * Labour participation ratega * daily wagega * SAFiga |

| Premature deaths cost | Number of deathsga * labour participation ratega * total expected future earnings * SAFga |

| Smoking breaks | Total populationga * labour participation ratega * smoking prevalencega * wages by minutesga * number of smoking break * length of smoking break (min) |

Here i=1,…,nth disease; j=gender; a=age group (5-year interval).

LOS, length of stay; SAF, smoking-attributable fraction.

Results

Baseline results—a conservative scenario

A conservative estimate of the social cost of smoking in Singapore in 2014 was at a minimum of US$479.8 million as shown in the baseline scenario in table 3. For all cost components, the cost of smoking was higher in men due to a higher smoking prevalence. Direct healthcare costs were relatively low, US$12.5 million for men and US$2.4 million for women. Absenteeism costs amounted to US$943 232 for men and US$52 601 for women. Presenteeism (smoking breaks) accounted for 56% of the total cost incurred, with US$239.2 million and US$29.8 million, respectively, for men and women. Finally, premature mortality cost society an additional US$195 million, taking up 40.6% of the total cost.

Table 3.

Overall cost of smoking

| Estimates | Baseline Estimates (US$) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |

| Direct healthcare cost | 12 513 611 | 2 398 949 |

| Absenteeism | 943 232 | 52 601 |

| Presenteeism | 239 214 947 | 29 750 790 |

| Premature mortality | 182 237 404 | 12 710 266 |

| Subtotal | 434 909 194 | 44 912 606 |

| Total | 479 821 799 | |

For direct healthcare cost, approximately half (50.4%) of the cost incurred by men was due to ischaemic heart disease (US$6.3 million), followed by lung cancer (US$2.8 million), COPD (US$1.7 million) and stroke (US$1.6 million). In women, it was lung cancer (US$1.1 million), followed by ischaemic heart disease (US$596 084), COPD (US$523 226) and stroke (US$193 954).

Loss of productivity due to diseases amounted to US$995 883. Out of the four diseases, the majority (50.4%) of the absenteeism cost for men was attributed to ischaemic heart diseases (US$420 178) followed by stroke, lung cancer and COPD, while for women it was lung cancer (US$28 331), followed by stroke, ischaemic heart disease and COPD (table 4).

Table 4.

Cost of smoking by disease

| Disease | Direct healthcare cost (US$) |

Absenteeism (US$) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Lung cancer | 2 828 307 | 1 085 685 | 194 457 | 28 331 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 6 302 899 | 596 084 | 420 178 | 10 141 |

| Stroke | 1 634 615 | 193 954 | 260 163 | 11 742 |

| COPD | 1 747 789 | 523 226 | 68 434 | 2387 |

| Subtotal | 12 513 611 | 2 398 949 | 943 232 | 52 601 |

| Total | 14 912 560 | 995 833 | ||

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Scenario analysis

We further explored four different scenarios that capture the uncertainty in our baseline assumptions as well as future developments: (1) increases in number of smoking breaks taken; (2) increases in smoking prevalence; (3) income growth; and (4) increased scope for presenteeism (table 5).

Table 5.

Scenarios affecting overall cost of smoking

| Estimates | Baseline |

Baseline+three smoking breaks |

Increase smoking prevalence |

Increase income growth |

Partial disability cost |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Direct healthcare cost | 12 513 611 | 2398 949 | 12 513 611 | 2 398 949 | 19 496 769 | 14 536 507 | 12 513 611 | 2 398 949 | 12 513 611 | 2 398 949 |

| Absenteeism | 943 232 | 52 601 | 943 232 | 52 601 | 878 172 | 153 125 | 943 232 | 52 601 | 943 232 | 52 601 |

| Presenteeism | 239 214 947 | 29 750 790 | 717 644 842 | 89 252 370 | 577 494 800 | 30 083 884 | 239 214 947 | 29 750 790 | 242 973 820 | 29 936 918 |

| Premature mortality | 182 237 404 | 12 710 266 | 182 237 404 | 12 710 266 | 156 339 540 | 31 655 398 | 229 369 294 | 15 779 891 | 182 237 404 | 12 710 266 |

| Subtotal | 434 909 194 | 44 912 606 | 913 339 088 | 104 414 185 | 754 209 281 | 76 428 914 | 482 041 084 | 47 982 231 | 438 668 066 | 45 098 734 |

| Total | 479 821 799 | 1 017 753 274 | 830 638 195 | 530 023 315 | 483 766 800 | |||||

Increasing the assumed frequency of smoking breaks has the highest impact on the overall cost of smoking. On the basis of a previous review of the literature in the USA and Canada, a reasonable upper-bound estimate of time loss would be 30 min a day of unsanctioned smoking.27 Applying this to our calculations would proportionally triple lost societal value, from US$270.0 million to US$807.9 million, and results in an overall SAE of about US$1.0 billion.

In our second scenario, we modelled a potential increase in smoking prevalence in a comparable population by using historical SAF and prevalence figures for South Korea as reported by Kang et al,28 extrapolating their SAF figures beyond age 64 years to correspond to our analysis. In 1992, prevalence of smoking was ∼66% for men and 7% for women in South Korea for people aged 30 years and over.29 Cost increases under this scenario mainly occurred under the presenteeism category, reaching US$607.6 million in total while overall SAE reached US$830.6 million, a 73.1% increase from our baseline scenario.

In the third scenario, projecting a 5% income growth (with a 3% inflation rate) increased the present-valued cost of premature deaths. For men, the figure increased from US$182.2 million to US$229.4 million and for women, it increased from US$12.7 million to US$15.8 million. Overall, SAE increased by 10.5% to US$530.0 million due to the increased mortality cost.

Finally, we included a fourth scenario to address the fact that beyond smoking breaks, presenteeism can also be caused by lower productivity while actively working (ie, partial disability). In the absence of such data for Singapore, we used the average count of partial disability work days from a sample of high-income countries in three categories (cardiovascular, respiratory and cancer) to proxy for this aspect of presenteeism cost.30 Further, including the value of partial disability days (at average wages) into our estimates of total productivity loss had a minimal impact. It increased the overall presenteeism cost from USD269.0 million to USD272.9 million, resulting in a 0.82% increase in overall cost of smoking to USD483.8 million. Since the impact is minimal and the estimates indirect, we excluded this from our baseline scenario, but presented the results here for completeness.

Discussion

This study estimated that cigarette smoking cost Singapore at least US$479.8 million in 2014. A majority of the cost is likely to come from presenteeism (US$269.0 million) and to be concentrated among males (US$435.0 million). In terms of diseases, ischaemic heart disease (US$7.3 million) and lung cancer (U$4.1 million) cost the most out of the four diseases, due to higher SAF figures and more costly treatments.

In 2014, Singapore generated US$908.5 million in tobacco excise tax revenues,31 a ‘benefit’ that surpassed this estimated societal cost. Our conservative baseline estimate of societal cost in 2014 is ∼10% lower than the range of US$530.4 million—US$660.8 million estimated for 1997.15 At 0.2% of the national GDP, this estimate is also comparatively low relative to published figures for Asian peers such as South Korea (0.6–1.2%),28 China (0.7%),32 Taiwan (0.4%)19 and Vietnam (1.0%).20

However, these findings by no means imply that the time for stringent tobacco control policy is over. We emphasise that the cost estimate should be interpreted as a minimum figure, underestimating the true societal cost. First, our methodology is limited by the constraints of data availability and most likely significantly understates the true costs. As noted, we are able to include only four smoking-related diseases for direct healthcare cost calculation. SAFs for mortality were used to calculate morbidity cost, although the disease-specific relative risks of the latter may be higher, leading to unattributed costs of healthcare and indirect morbidity. Smoking-related costs incurred by smokers, passive smokers and ex-smokers in the primary healthcare sector, rehabilitation care and nursing homes, or due to self-medication, were also excluded due to a lack of reported data. While this study has attempted to capture the cost of presenteeism, we could not include other indirect costs such as the cost of implementing tobacco control programmes, cost of cigarette purchases and the potentially large externality costs of secondhand smoke. Finally, we did not account for the rising use of a variety of alternative tobacco products for which data are not readily available and will not be for some time.

Comparisons across time and peer groups are further complicated by methodological differences and may be misleadingly optimistic if taken purely at face value. The difference between our estimates for 2014 and the estimates for 1997 suggests a fall in total societal costs, consistent with survey data showing a fall in smoking prevalence from 15.1% in 1998 to 14.3% in 2010. Shorter hospital stays in the present day, updated treatment procedures, fewer smoking-related deaths and deaths at an older age could also potentially play a role. However, the study was not designed to test these hypotheses formally due to fundamental differences in data sources and the resulting calculations. Using restricted MOH data, Quah et al accounted for the direct healthcare cost of five conditions (oesophageal cancer, larynx neoplasm, trachea, bronchus and lung cancer, ischaemic heart and cerebrovascular heart diseases). In contrast, this study relied on publicly available statistics on hospital bills for only four conditions (lung cancer, COPD, ischaemic heart diseases and stroke). Second, Quah et al15 assumed that unit costs are uniformly based on the charges of Class A wards (the highest class of service in public hospitals, equivalent to private wards), which overestimates total population costs. Smoking prevalence tends to be higher among lower-income households, leading to a large fraction of patients who use lower-class wards with more limited amenities, in which unit costs are significantly lower (even after accounting for government subsidies). Our estimates included data from all ward classes in the public hospitals as well as data from private hospitals. In this respect, the cost estimated in this study is a more accurate reflection of inpatient medical costs at the population level. We also noted that our study methodology was not always more conservative than Quah et al,15 as a broader consideration of lost productivity was included.

The cross-country comparisons are subjected to similar methodological caveats. For example, Kang et al28 estimated the cost of 22 smoking-related diseases in South Korea while Yang et al32 also included caregivers' cost in the calculation of the monetary value of indirect morbidity in China.

Looking to the future, in spite of stringent controls and health promotion programmes, declines in smoking prevalence have reversed in certain groups. Smoking prevalence has increased among adolescent men from 7.7% in 2009 to 8.8% in 2012. In addition, overall female smoking prevalence has also risen from 3.3% in 2004 to 4.2% in 2010. If these trends persist, the future social cost of smoking will correspondingly rise. As Singapore ages, rising healthcare costs are likely to further compound this increase. Finally, with new policy efforts to increase overall productivity growth and employment in old age, indirect losses from morbidity and premature mortality will also become more significant.

To address the limitations of our study and smoking research in Singapore more generally, further studies will be needed including better research on the SAF of morbidity, estimates of patient volumes and costs in the primary care sector and studies of cost incurred by caregivers. Over the longer term, ongoing efforts to develop integrated national electronic health records will also help to enable systematic collection of data on other risk factors and diseases as part of a more robust platform for measuring the socioeconomic burden of diseases over time.

At the same time, various stakeholders can already benefit from the insights of this work. Taken together, our findings suggest that for Singapore, implementing new and more effective efforts to prevent uptake of smoking among the young is an urgent need, while encouraging quitting among current smokers at every age still remains a priority. The MOH and MOM need to work together with employers to reduce the cost of lost productivity in workplaces, and other entities outside the health system such as the Ministry of Education to address smoking at younger ages. The case of Singapore demonstrates that effective long-term tobacco control must be firm and sustained and requires adaptation and multisector collaborations in the face of new and emerging trends in tobacco use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Ministry of Health for providing the data and technical assistance to the project, as well as colleagues at the Health Promotion Board of Singapore for their invaluable insights and perspective.

Footnotes

Contributors: JY and CC established the analytical framework and supervised the data analysis process. BPC and CC analysed and interpreted the results. BPC drafted the manuscript which was further revised by JY for intellectual content. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Forey BA, Thornton AJ, Lee PN. Systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence relating smoking to COPD, chronic bronchitis and emphysema. BMC Pulm Med 2011;11:36 10.1186/1471-2466-11-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y, Pleasants RA, Croft JB, et al. . Smoking duration, respiratory symptoms, and COPD in adults aged ≥45 years with a smoking history. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015;10:1409–16. 10.2147/COPD.S82259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xue WQ, Qin HD, Ruan HL, et al. . Quantitative association of tobacco smoking with the risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a comprehensive meta-analysis of studies conducted between 1979 and 2011. Am J Epidemiol 2013;178:325–38. 10.1093/aje/kws479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gandini S, Botteri E, Iodice S, et al. . Tobacco smoking and cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 2008;122:155–64. 10.1002/ijc.23033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee PN, Forey BA, Coombs KJ. Systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence in the 1900s relating smoking to lung cancer. BMC Cancer 2012;12:385 10.1186/1471-2407-12-385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haire-Joshu D, Glasgow RE, Tibbs TL. Smoking and diabetes. Diabetes Care 1999;22:1887–98. 10.2337/diacare.22.11.1887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Ji J, Liu YJ, et al. . Passive smoking and risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. PLoS One 2013;8:e69915 10.1371/journal.pone.0069915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Xu M, Zhang J, et al. . Risk factors for chronic and recurrent otitis media-a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e86397 10.1371/journal.pone.0086397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. WHO global report mortality attributable to tobacco. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44815/1/9789241564434_eng.pdf (accessed 6 Dec 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Health. National health survey 2010. Singapore: Ministry of Health, 2011. https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/Publications/Reports/2011/national_health_survey2010.html (accessed 9 Dec 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang R. Singapore budget 2014: duties on alcohol, tobacco and gambling to rise. The Straits Times. 2014. http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/singapore-budget-2014-duties-on-alcohol-tobacco-and-gambling-to-rise (accessed 10 Dec 2015).

- 12.Health Promotion Board. I quit 28-day countdown. Singapore: Health Promotion Board, 2016. http://www.hpb.gov.sg/HOPPortal/health-article/HPB050010 (accessed 11Aug 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health. Ban on shisha to be effected from 28 November 2014 2014. https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/pressRoom/pressRoomItemRelease/2014/ban-on-shisha-to-be-effected-from-28-november-2014.html (accessed 15 Dec 2015).

- 14.Ministry of Health. First phase of the ban on emerging tobacco products to take effect from 15 Dec 2015 2015. https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/pressRoom/pressRoomItemRelease/2015/first-phase-of-the-ban-on-emerging-tobacco-products-to-take-effe.html (accessed 30 Dec 2015).

- 15.Quah E, Tan KC, Saw SL, et al. . The social cost of smoking in Singapore. Singapore Med J 2002;43:340–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luce BR, Schweitzer SO. Smoking and alcohol abuse: a comparison of their economic consequences. N Engl J Med 1978;298:569–71. 10.1056/NEJM197803092981012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rice DP, Hodgson TA, Sinsheimer P, et al. . The economic costs of the health effects of smoking, 1984. Milbank Q 1986;64:489–547. 10.2307/3349924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Economics of tobacco toolkit: assessment of the economic costs of smoking. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44596/1/9789241501576_eng.pdf (accessed 8 Nov 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sung HY, Chang LC, Wen YW, et al. . The costs of smoking and secondhand smoke exposure in Taiwan: a prevalence-based annual cost approach. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005199 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoang Anh PT, Thu LT, Ross H, et al. . Direct and indirect costs of smoking in Vietnam. Tob Control 2016;25:96–100. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Health. Hospital bill sizes. Singapore: Ministry of Health, 2014. https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/costs_and_financing/hospital-charges/Total-Hospital-Bills-By-condition-procedure.html (accessed 6 Mar 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministry of Manpower. Report: labour force in Singapore, 2014. Singapore: Ministry of Manpower, 2014. http://stats.mom.gov.sg/Pages/Labour-Force-In-Singapore-2014.aspx (accessed 9 Mar 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Begg S, Vos T, Barker B, et al. . The burden of disease and injury in Australia 2003. Australia: Institute of Health and Welfare, 2007. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442467990 (accessed 14 Aug 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministry of Health. Revised healthcare subsidy rates for permanent residents. Singapore: Ministry of Health, 2012. https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/pressRoom/pressRoomItemRelease/2012/revised_healthcaresubsidyratesforpermanentresidents0.html (accessed 18 Dec 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brent RJ. Chapter 11: cost–benefit analysis and the human capital approach, 2003.

- 26.Ministry of Manpower. Summary table: income. Singapore: Ministry of Manpower, 2015. http://stats.mom.gov.sg/Pages/Income-Summary-Table.aspx (accessed 14 Aug 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berman M, Crane R, Seiber E, et al. . Estimating the cost of a smoking employee. Tob Control 2014;23:428–33. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang HY, Kim HJ, Park TK, et al. . Economic burden of smoking in Korea. Tob Control 2003;12:37–44. 10.1136/tc.12.1.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HJ, Kim Y, Cho Y, et al. . Trends in the prevalence of major cardiovascular disease risk factors among Korean adults: results from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1998–2012. Int J Cardiol 2014;174:64–72. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.03.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruffaerts R, Vilagut G, Demyttenaere K, et al. . Role of common mental and physical disorders in partial disability around the world. Br J Psychiatry 2012;200:454–61. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.097519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ministry of Finance. Singapore Budget 2015. Singapore: Ministry of Finance, 2015. http://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/budget_2015/revenueandexpenditure/RevenueandExpenditureEstimates.aspx (accessed 20 Jan 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang L, Sung HY, Mao ZZ, et al. . Economic costs attributable to smoking in China- update and an 8-year comparison, 2000–2008. Tob Control 2011;20:266–72. 10.1136/tc.2010.042028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.