Summary

During vertebrate embryogenesis, most of the mesodermal tissue posterior to the head forms from a progenitor population that continuously adds blocks of muscles (the somites) from the back end of the embryo. Recent work in less commonly studied arthropods, the flour beetle Tribolium and the common house spider, provides evidence suggesting that this posterior growth process might be evolutionarily conserved, with canonical Wnt signaling playing a key role in vertebrates and invertebrates. We discuss these findings as well as other evidence that suggests that the genetic network controlling posterior growth was already present in the last common ancestor of the bilateria. We also highlight other interesting commonalities as well as differences between posterior growth in vertebrates and invertebrates, suggest future areas of research, and hypothesize that this process may facilitate evolution of animal body plans.

Comparison of body plans across the animal kingdom was an essential exercise leading to Darwin’s theory of evolution, and continues to be a central aspect of biological study. Body plan similarities provide us with insight into our own ancestral origins, while differences can illuminate what makes us unique as humans. In the molecular era, developmental biologists possess a particularly insightful view of this process, as we begin to understand how the genomic code translates into adult form through the process of embryogenesis.

A major feature of early vertebrate body development is posterior growth, which accounts for the formation of most of the body posterior to the head. The clearly identifiable feature of posterior growth is the addition of segmented blocks of muscle tissue (called somites) in an anterior to posterior fashion, as well as the growth of the spinal cord that forms between the somites. Posterior growth is accomplished by a group of progenitor cells located in a growth zone at the posterior-most end of the embryo, which continuously provides cells to the growing body [1]. Posterior growth contributes to the vast array of morphological diversity that we see among vertebrate species. The long slender body of a corn snake can grow to over 2 meters in length with over 300 segments, whereas a zebrafish has variably 30–35 segments and reaches a final size of 5 cm [2]. Emerging data from non-model invertebrate species indicates that posterior growth is a common feature of body formation throughout the animal kingdom. In this review, we will discuss the possibility that a conserved molecular pathway governs posterior growth in all animals.

A Wnt – Caudal pathway is required for posterior growth

The canonical Wnt signaling pathway is an essential developmental regulator that can be found in all extant taxa of metazoans [3]. In vertebrates, Wnt signaling has an early role in establishing the anterior-posterior axis [4], and is then later critically required for posterior growth [5 and references therein]. In both mouse and zebrafish vertebrate model systems, loss of Wnt signaling results in a severely truncated body, which forms only the head and anterior part of the trunk. The expression of Wnt signaling components in progenitor cells of the growth zone in other vertebrate models, such as frog and chicken, suggests that this mechanism is utilized for body plan development by all vertebrates. The Wnt pathway exerts its effects on posterior growth at least in part by directly regulating the expression of the transcription factor Caudal, which in turn activates a suite of Hox genes expressed in the posterior of the embryo. Like the Wnt pathway, loss of Caudal in mouse and zebrafish results in embryos having only a head and anterior trunk [6, 7]. Two papers published recently in this journal indicate that posterior growth through the Wnt-Caudal pathway is conserved in insects and spiders [8, 9], leading to the intriguing hypothesis that this genetic network is an ancient mechanism of body formation.

A comparative look at posterior growth – the importance of “non-model” systems

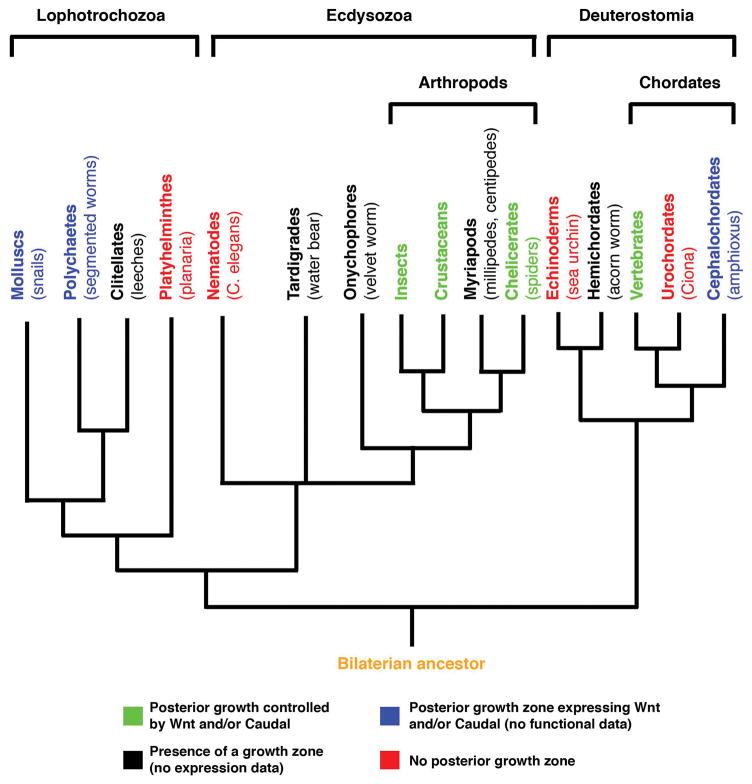

The majority of animals that inhabit the earth today are classified as bilaterians, having both anterior-posterior (head-tail) and dorsal-ventral (back-belly) axes. The bilaterians are divided into three groups, Lophotrochozoa, Ecdysozoa, and our own group, Deuterostomia (Figure 1). Comparing developmental modes between animals of each group is important for understanding how animals evolved. Traditional comparisons of the molecular control of development have been with genetic “model” systems, such as the fruit fly Drosophila and the nematode worm C. elegans, both belonging to the Ecdysozoa. But we now realize that these animals undergo derived modes of development, and are not ideal for evolutionary comparisons (Box 1). For example, Drosophila belongs to the long germ-band insects, which completely lack a posterior growth zone and form all of their segments simultaneously [10, 11]. A better evolutionary comparison is with short germ band insects, which represent a more basal mode of arthropod development [10, 11]. The vast majority of insects orders are short (or intermediate) germ band, which have a posterior growth zone and form posterior segments in an anterior to posterior progression [10, 11]. In fact, on a gross morphological level, the short germ band mode of posterior growth is strikingly similar to that of vertebrates (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Evidence of posterior growth among the bilaterians.

A phylogenetic tree illustrating the evolutionary relationship between members of the three bilaterian groups, and highlighting our current knowledge of posterior growth in each clade (only clades discussed in the text are illustrated).

Box 1. The importance of derived vs. basal.

The terms derived and basal refer to the evolutionary state of an existing taxon relative to its presumed ancestor. If an animal is significantly different than its ancestor, it is said to be derived, while one that is similar is basal. Importantly, derived characteristics, which make an animal different than its ancestor, can arise by either acquiring new characteristics or losing ancestral traits. When making evolutionary comparisons, it is more informative to use basal animals as they are representative of the ancestral state.

Figure 2. Posterior growth in vertebrates and short germ band insects.

A comparison of posterior growth in vertebrate and short germ band insects highlights the striking similarity of this process between these distantly related clades. In vertebrates, the paired somites are blocks of mesoderm that produce muscle, cartilage and bone whereas the ectoderm is unsegmented. In insects, the segments contain both ectoderm and paired somites that produce a number of mesodermal derivatives.

The fact that posterior growth and segmentation look the same between short germ band insects and vertebrates does not necessarily indicate that they are evolutionarily homologous. There are many instances throughout the animal kingdom of convergent evolution, where two structures that look similar or serve the same function were achieved by different means [12]. One way in which we can strengthen the argument of homology is to compare the genetic network underlying the development of two similar structures. If the posterior growth zones of insects utilize the same genes as vertebrates, the Wnt pathway and Caudal, they are more likely to be homologous processes [13].

New evidence strongly supports homologous posterior growth between vertebrates and arthropods

Until very recently, loss of function of the Wnt signaling pathway in short germ band insects had not been examined, making a definitive justification for posterior growth homology difficult. An exciting result clearing the way for this conclusion was recently obtained in the flour beetle. Like vertebrates, the posterior growth zone of the short germ band flour beetle (Tribolium) also expresses wnts and caudal [14, 15]. Eliminating the expression of two wnt genes with RNA interference caused severe posterior truncations resulting from a failure to maintain the posterior growth zone [8]. While it is not known whether caudal is a direct target of Wnt signaling in the flour beetle, loss of Caudal function causes severe posterior truncation, suggesting that the genetic pathway regulating posterior growth is conserved between vertebrates and flour beetles [16].

Further support for this conservation among insects comes from crickets. While specific Wnt ligands involved in posterior growth have not been identified, loss of β-catenin, the downstream effector of canonical Wnt signaling, causes severe posterior truncations [17]. Moreover, Caudal functions downstream of β-catenin and is required for posterior growth, confirming the genetic hierarchy seen in vertebrates [18].

Spiders are members of the chelicerates, which are grouped together with insects in the arthropod clade (Figure 1). In this organism, eliminating expression of a single wnt gene caused posterior truncation, as well as an absence of caudal expression [9]. In another arthropod clade, the crustaceans, the activity of Caudal was shown to be required for the posterior growth of Artemia [16]. Together, these results indicate that posterior growth regulated by the Wnt -> Caudal pathway is highly conserved among arthropods and vertebrates.

What about the other Ecdysozoa and deuterostome clades?

We have thus far skipped the non-arthropod Ecdysozoa and the non-vertebrate deuterostomes as a matter of necessity rather than convenience. Much of the molecular data needed to make comparisons with other species simply does not yet exist. For example, other basal Ecdysozoan taxa display clear posterior growth and segmentations, but wnt and caudal gene expression or function has not been examined (Figure 1).

What about posterior growth in other deuterostome clades? There are two other chordate clades besides the vertebrates, the urochordates and the cephalochordates (Figure 1)[19]. The ascidian Ciona is an emerging model system within the urochordates, but like Drosophila it is considered highly derived, and does not contain a posterior growth zone. Amphioxus on the other hand, a member of the cephalochordates, clearly undergoes posterior growth and somitogenesis. Wnt ligands are expressed in the posterior growth zone, but loss of function studies have not been performed due to the technical difficulties with these animals [20]. Outside of the chordates, the other major groups within the deuterostomes are the hemichordates and echinoderms. Posterior growth occurs in hemichordates (and arguably in echinoderms), but morphologically speaking, does not closely resemble vertebrate or insect posterior growth [21]. It is also not known whether wnts and caudal are expressed in the regions where posterior growth is occurring.

The enigmatic Lophotrochozoa

The fact that the regulation of posterior growth is conserved between insects and vertebrates suggests that their last common ancestor also displayed posterior growth controlled by Wnt signaling and Caudal. Based on modern bilaterian phylogenies, the last common ancestor of insects and vertebrates gave rise to all bilaterians [22] (Figure 1). We should therefore be able to detect similar body plan development in Lophotrochozoan embryos.

The Lophotrochozoa are by far the least-studied group among the three major bilaterian clades. Emerging data from the Lophotrochozoa indicate that Wnts and Caudal are present in a posterior growth zone (Figure 1), suggesting that the mechanism of Wnt controlled posterior growth is also conserved among this group. However, the definitive functional experiments have yet to be done in Lophotrochozoa, and represent an essential missing piece to our overall view of bilaterian posterior growth.

A chordate innovation for Wnt controlled posterior growth

Derivations of posterior growth can also involve novel lineage specific modifications to the core regulatory program. Wnt signaling appears to be at the top of the hierarchy of posterior growth zone regulation in vertebrates. The precise timing of wnt expression in the growth zone during development can control the length of the animal. In zebrafish, artificially inhibiting the Wnt pathway at various times during posterior growth results in embryos with varying lengths and segment number. The earlier Wnt signaling is inhibited, the shorter the embryo and the fewer the segments [5]. This suggests that in a creature such as the snake, which forms a large number of segments over many days [2], Wnt signaling is maintained at the posterior end for a very long time.

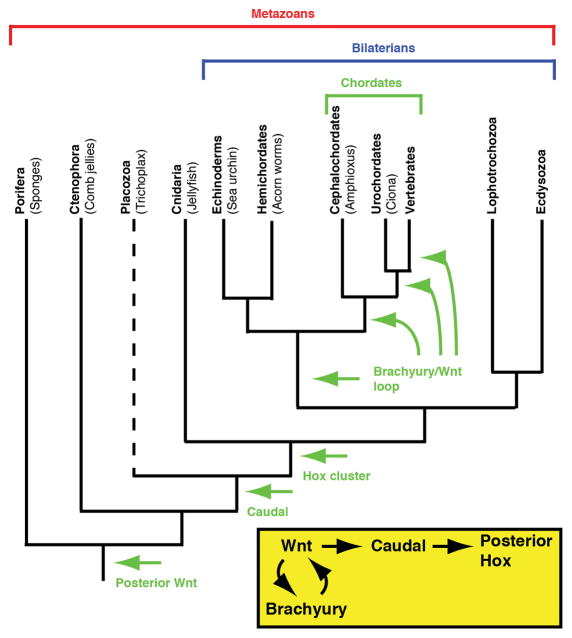

A direct downstream target of Wnt signaling in vertebrates is brachyury, a transcription factor that is itself required for posterior growth [23, 24]. We recently showed in zebrafish that the primary role of Brachyury during posterior growth is to directly regulate wnt expression, thereby creating a positive autoregulatory loop [5]. In the absence of Brachyury, Wnt signaling is initiated but not maintained, and posterior growth ceases. Interestingly, brachyury is expressed in the posterior growth zone of flour beetles and crickets, although it is not required for posterior growth, indicating that it does not regulate Wnt signaling in insects [25, 26]. This raises the intriguing possibility that Brachyury, since it was already expressed in the right location, was co-opted into the posterior growth genetic network along the deuterostome lineage, perhaps to prolong the amount of time Wnt signaling is active in the posterior growth zone in order to allow prolonged periods of posterior growth. When in animal evolution the Brachyury/Wnt autoregulatory loop was established remains to be determined, although clearly it was present along the vertebrate lineage (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The emergence of the posterior growth pathway.

The essential genetic components of the posterior growth pathway, including the recent innovation of a Brachyury/Wnt loop, are shown in the yellow box. The first appearance of these genetic components during metazoan evolution is indicated on the phylogenetic tree. Dotted line indicates uncertainly in placement of the Placozoa.

Does Wnt controlled posterior growth occur in unsegmented animals?

The animals in which posterior growth has been shown to be Wnt dependent, the vertebrates and arthropods, are clearly segmented. In vertebrates, the posteriorly localized Wnt signal has also been implicated in coordinating the segmentation process [27]. In addition, other groups with overt segmentation, such as cephalochordates and polychaetes, have posteriorly localized wnt [20, 28, 29], although it is not known whether growth and segmentation are coordinated by Wnts in these animals. The association with Wnt controlled posterior growth and segmentation (working through the Notch pathway) raises the possibility that these two processes are intricately, and perhaps obligately, linked. It is clear that segmentation can be achieved without posterior growth, as in the case of Drosophila, but whether posterior growth can occur without segmentation is unknown. The molluscs, which exhibit posterior growth but are not segmented, provide a unique opportunity to examine this question. Currently, wnt expression during posterior growth in molluscs has not been examined.

Arguments have been made for and against the hypothesis that the common bilaterian ancestor (called the urbilaterian) was segmented [30, 31]. Regardless of the state of segmentation, we favor the idea that the urbilaterian exhibited posterior growth, an idea which has been previously raised [21]. Given the association of Wnt controlled posterior growth with segmentation, and the possibility that they are obligately linked, the emergence of posterior growth in the urbilaterian may have required the simultaneous acquisition of segmentation. Coordination of posterior growth may have been simplified by the process of adding serially repeating blocks of tissue, rather than extending an already complex body. The emergence of posterior growth, and possibly segmentation, in the urbilaterian may also have been a necessary prerequisite to the Cambrian explosion, where the fossil record exhibits a sudden burst in morphological diversity among animals. Extending the body axis posteriorly may have provided a mechanism for body plan diversification, which could be subsequently modified to fit specific habitat needs. Extant clades showing clear posterior growth and segmentation, such as the vertebrates, arthropods and annelids, exhibit a disproportionate amount of morphological diversity compared to clades lacking posterior growth.

The origins of a Wnt – Caudal posterior growth mechanism

All bilaterians have hox genes, which are transcription factors that specify regional identity along the anterior-posterior axis [30]. Anteriorly expressed hox genes specify the head, while posteriorly expressed hox genes specify the back end. In vertebrates and arthropods (and likely all bilaterians), Caudal activates the expression of posterior hox genes, thereby imparting posterior identity to regions in which it is expressed. Using this Wnt->Caudal->Hox hierarchy, we can attempt to trace back the origins of posterior growth based on when these genes first appear along the metazoan lineage (Figure 3).

There are four metazoan phyla outside of the bilaterians, Porifera (sponges), Ctenophora (comb jellies), Placozoa (Trichoplax), and Cnidaria (sea anemones, corals, jellyfish). There are no clear examples of posterior growth among these groups, despite the fact that all contain Wnts [32]. Sponges, which represent the evolutionarily oldest branch of the metazoan phylogeny, have been shown to have posteriorly localized wnt expression in their larvae, the role of which is unknown [33]. During evolution, this posteriorly localized Wnt signal could have been co-opted into a new role of Caudal regulation. Caudal does not show up until Placozoa, and finally Hox clusters appear in Cnidaria [3 and references therein]. While the Hox cluster is present in Cnidarians, it lacks the full extent of trunk Hox genes seen in bilaterians [21]. Posterior growth may require these additional genes to specify an extended body axis. Based on the comparative data discussed earlier, combined with the ancestry of the genes involved in posterior growth, this process of body plan development likely evolved at or around the emergence of the urbilaterian. A further refinement occurred somewhere along the deuterostome lineage as discussed above, imparting a Wnt/Brachyury loop to sustain posterior growth (Figure 3).

Future directions

The studies discussed in this review have provided the outline of an ancestral mechanism for the molecular regulation of posterior growth, and have also opened up many new questions to pursue. In the variety of non-model organisms that show posterior growth, it will be extremely valuable to determine if they express wnts and caudal, and important to investigate whether inhibition of the function of these genes leads to abnormalities in posterior growth. With the increasing availability of genome information for these organisms, as well as the development of tools such as morpholinos and RNAi, these types of studies are now feasible. In vertebrates, caudal is clearly a direct target of Wnt signaling, but this has yet to be established for other organisms. Demonstrating direct regulation of the caudal promoter in invertebrate systems by Wnt signaling would be a valuable addition in establishing homology of mechanism. Similarly, examining other deuterostomes, particularly the basal chordate amphioxus, would help establish when the Wnt/Brachyury loop showed up in development.

While we have focused on Wnt as a regulator of caudal expression, Wnt signaling can activate a plethora of genes depending on the cellular context, including genes involved in cell growth, segmentation, and embryonic patterning. In the years to come, identifying which Wnt targets are activated in the posterior growth zone of different bilaterians will be essential for understanding what aspects of posterior growth are ancestral, and which have evolved to create the diversity we see today.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply indebted to Billie Swalla for comments on this manuscript and for many valuable discussions. B.L.M. and D.K. are supported by an American Cancer Society postdoctoral fellowship and NIH grant GM079203.

References

- 1.Holley SA. The genetics and embryology of zebrafish metamerism. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:1422–1449. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomez C, Ozbudak EM, Wunderlich J, Baumann D, Lewis J, Pourquie O. Control of segment number in vertebrate embryos. Nature. 2008;454:335–339. doi: 10.1038/nature07020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan JF, Baxevanis AD. Hox, Wnt, and the evolution of the primary body axis: insights from the early-divergent phyla. Biol Direct. 2007;2:37. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-2-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schier AF, Talbot WS. Molecular genetics of axis formation in zebrafish. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:561–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin BL, Kimelman D. Regulation of canonical Wnt signaling by Brachyury is essential for posterior mesoderm formation. Dev Cell. 2008;15:121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chawengsaksophak K, de Graaff W, Rossant J, Deschamps J, Beck F. Cdx2 is essential for axial elongation in mouse development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7641–7645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401654101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimizu T, Bae YK, Muraoka O, Hibi M. Interaction of Wnt and caudal-related genes in zebrafish posterior body formation. Dev Biol. 2005;279:125–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolognesi R, Farzana L, Fischer TD, Brown SJ. Multiple Wnt genes are required for segmentation in the short-germ embryo of Tribolium castaneum. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1624–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGregor AP, Pechmann M, Schwager EE, Feitosa NM, Kruck S, Aranda M, Damen WG. Wnt8 is required for growth-zone establishment and development of opisthosomal segments in a spider. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1619–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu PZ, Kaufman TC. Short and long germ segmentation: unanswered questions in the evolution of a developmental mode. Evol Dev. 2005;7:629–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2005.05066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg MI, Lynch JA, Desplan C. Heads and tails: Evolution of antero-posterior patterning in insects. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wake DB. Homoplasy: the result of natural selection, or evidence of design limitations? Am Nat. 1991;138:543–567. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abouheif E. Establishing homology criteria for regulatory gene networks: prospects and challenges. Novartis Found Symp. 1999;222:207–221. doi: 10.1002/9780470515655.ch14. discussion 222–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulz C, Schroder R, Hausdorf B, Wolff C, Tautz D. A caudal homologue in the short germ band beetle Tribolium shows similarities to both, the Drosophila and the vertebrate caudal expression patterns. Dev Genes Evol. 1998;208:283–289. doi: 10.1007/s004270050183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolognesi R, Beermann A, Farzana L, Wittkopp N, Lutz R, Balavoine G, Brown SJ, Schroder R. Tribolium Wnts: evidence for a larger repertoire in insects with overlapping expression patterns that suggest multiple redundant functions in embryogenesis. Dev Genes Evol. 2008;218:193–202. doi: 10.1007/s00427-007-0170-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Copf T, Schroder R, Averof M. Ancestral role of caudal genes in axis elongation and segmentation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17711–17715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407327102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyawaki K, Mito T, Sarashina I, Zhang H, Shinmyo Y, Ohuchi H, Noji S. Involvement of Wingless/Armadillo signaling in the posterior sequential segmentation in the cricket, Gryllus bimaculatus (Orthoptera), as revealed by RNAi analysis. Mech Dev. 2004;121:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shinmyo Y, Mito T, Matsushita T, Sarashina I, Miyawaki K, Ohuchi H, Noji S. caudal is required for gnathal and thoracic patterning and for posterior elongation in the intermediate-germband cricket Gryllus bimaculatus. Mech Dev. 2005;122:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swalla BJ, Smith AB. Deciphering deuterostome phylogeny: molecular, morphological and palaeontological perspectives. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:1557–1568. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schubert M, Holland LZ, Stokes MD, Holland ND. Three amphioxus Wnt genes (AmphiWnt3, AmphiWnt5, and AmphiWnt6) associated with the tail bud: the evolution of somitogenesis in chordates. Dev Biol. 2001;240:262–273. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs DK, Hughes NC, Fitz-Gibbon ST, Winchell CJ. Terminal addition, the Cambrian radiation and the Phanerozoic evolution of bilaterian form. Evol Dev. 2005;7:498–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2005.05055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn CW, Hejnol A, Matus DQ, Pang K, Browne WE, Smith SA, Seaver E, Rouse GW, Obst M, Edgecombe GD, et al. Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life. Nature. 2008;452:745–749. doi: 10.1038/nature06614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnold SJ, Stappert J, Bauer A, Kispert A, Herrmann BG, Kemler R. Brachyury is a target gene of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Mech Dev. 2000;91:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamaguchi TP, Takada S, Yoshikawa Y, Wu N, McMahon AP. T (Brachyury) is a direct target of Wnt3a during paraxial mesoderm specification. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3185–3190. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.24.3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berns N, Kusch T, Schroder R, Reuter R. Expression, function and regulation of Brachyenteron in the short germband insect Tribolium castaneum. Dev Genes Evol. 2008;218:169–179. doi: 10.1007/s00427-008-0210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shinmyo Y, Mito T, Uda T, Nakamura T, Miyawaki K, Ohuchi H, Noji S. brachyenteron is necessary for morphogenesis of the posterior gut but not for anteroposterior axial elongation from the posterior growth zone in the intermediate-germband cricket Gryllus bimaculatus. Development. 2006;133:4539–4547. doi: 10.1242/dev.02646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dequeant ML, Pourquie O. Segmental patterning of the vertebrate embryonic axis. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:370–382. doi: 10.1038/nrg2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schubert M, Holland LZ, Panopoulou GD, Lehrach H, Holland ND. Characterization of amphioxus AmphiWnt8: insights into the evolution of patterning of the embryonic dorsoventral axis. Evol Dev. 2000;2:85–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2000.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seaver EC, Kaneshige LM. Expression of ‘segmentation’ genes during larval and juvenile development in the polychaetes Capitella sp. I and H. elegans. Dev Biol. 2006;289:179–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Robertis EM. Evo-devo: variations on ancestral themes. Cell. 2008;132:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rivera AS, Weisblat DA. And Lophotrochozoa makes three: Notch/Hes signaling in annelid segmentation. Dev Genes Evol. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00427-008-0264-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nichols SA, Dirks W, Pearse JS, King N. Early evolution of animal cell signaling and adhesion genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12451–12456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604065103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adamska M, Degnan SM, Green KM, Adamski M, Craigie A, Larroux C, Degnan BM. Wnt and TGF-β expression in the sponge Amphimedon queenslandica and the origin of metazoan embryonic patterning. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]